from the Labor Commission of Solidarity

July 16, 2014

Preamble

This February, the Solidarity Labor Commission held a two-day retreat at which we reflected on Solidarity’s labor work and the rank-and-file union perspective that has guided it for decades. This outline of a renewed strategic perspective is what emerged from our discussions. Although there is much here that is new, this perspective reflects our attempt to interpret the trajectory of union reform work since the 1980s and the political dynamics of the current period through the lens of Solidarity’s long-standing commitment to a politics of “socialism from below.”

The Rank and File Strategy (best described in Kim Moody’s paper of the same name) directs socialists to root our political work in the activist layer of the working class by prioritizing the development of militant, rank and file, “grassroots” organizations. The Rank and File Strategy points us to the need for for working class self-organization independent of the labor bureaucracy and the Democratic Party in order to build a fighting labor movement and recruit workers to socialist ideas. For socialists, these militant and democratic formations within the labor movement play several essential roles. They ensure that socialist politics develop from an understanding of the actual conditions of the working class. They work to enlarge the activist layer of the working class, bringing more rank and file workers into struggles and experiences that draw out militancy and class consciousness. They provide an active and conscious rank and file base to press against the conservatizing and bureaucratic tendencies of union officials. And these efforts help to connect union militants with socialist ideas and organization. As socialists who believe in revolutionary transformation, the broader aim of this work is always to develop the capacity of the working class for democratic self-organization–the only solid basis upon which to build a socialist society free of bureaucratic domination.

In practice, Solidarity members implemented the Rank and File Strategy primarily by building rank and file caucuses within major unions—most notably and successfully, the Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU). We have also worked, with varying degrees of success, to build solidarity between militant insurgent movements in different local and international unions, and to foster the creation of a left milieu in the labor movement. We focused on work within unions for good reasons. Unions, with all their shortcomings, bring together millions of workers across the many lines of division and oppression that divide the working class. Unions bring workers together at the point of production—where some workers have the ability to interfere with profit-making or with the functioning of the social order more generally. Unions provide a relatively stable organizational setting in which sustained political work is possible. And unions are, by definition, organizations of workers and are therefore always potentially oppositional.

While the Rank and File Strategy provides socialists with an organizing method and an understanding of the relations between democracy, bureaucracy and radicalization, it does not automatically provide a clear political direction for our work. In its most narrow application, much socialist rank and file union organizing has focused on questions of internal union democracy and efforts to mount anti-concession struggles. While those fights remain critically important, the main argument of this paper is that a broader approach to the Rank and File Strategy is necessary and possible – especially under today’s conditions. This broader approach would emphasize work to build broad “class-wide” transitional organizations and movements that extend well beyond sectoral, formal union structures and the workplace setting, and which pose broad demands that speak to the needs of the working class as a whole.

Why do we need a broader, “class-wide,” approach to transitional organizations today?

Although the official labor movement, with 16 million members, remains an important potential source of social power for workers, the great majority of workers are not in unions and do not look to unions for solutions to their daily problems. Perhaps more importantly, though, our historic emphasis on the power that comes from workers’ position at the point of production lacks balance. In the first place, workers’ dependence on particular workplaces and companies can promote conservatism, competitiveness, and class collaboration as well as militancy. Indeed, we were not always able to combat the tendency of many dedicated, militant workers to focus exclusively on their particular union or industry. And, given the changes in the structure of the economy and the drastic decline in union density, most workers today are not in industries where their position in production provides significant, direct social power. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, our traditional emphasis on the point of production as the source of working class power neglects the social power that comes from the political practice of solidarity—and the political weakness that comes from failing to practice solidarity.

It is certainly true that bureaucratic mis-leadership hobbled the industrial unions. But the bureaucracy’s failing was not only its reluctance to use militant tactics like strikes and work-to-rule—something that the Left rightly emphasizes. The labor bureaucracy also failed to position the unions as fighters for the whole working class. This allowed capital to portray unions and union members as a special interest, and to isolate the labor movement from its organic base of support in the broad working class. Imagine how history might have been different if the industrial unions had never given up the fight for universal health care or if the UAW had launched a real assault on racism and disinvestment in Detroit in the 1950s when the writing was already on the wall.

Today, in order to rebuild class power for workers we need to construct solidaristic, class-wide, transitional organizations and movements that unite the working class against austerity and pose more universal demands as solutions. We cannot hope to accomplish this from a relatively narrow perch within formal union structures. Instead, we need to awaken the social power that is inherent in the unions, in alliance with other workers and working-class communities. As the Wisconsin Uprising and the Chicago Teachers Union both demonstrate, reviving the social power of unions requires sustained rank and file rebellion. And the best way to provide an impetus to rank and file rebellion today may be to alter the broader social and political context in which union members assess the prospects of a fight against the bureaucracy, the bosses, and the state.

This paper represents an effort by the Labor Commission of Solidarity to grapple with these questions, draw lessons from recent struggles and contribute to discussion about socialist labor strategy in these times. This document is not intended as a comprehensive program or a detailed plan of work. We have intentionally kept its scope narrow, in order to focus on those points that we find most essential to rebuilding the Left and maximizing the potential of emerging anti-austerity struggles. This document is intended as a starting point not an end point. Coming to grips with the challenges we face will require much wider discussion and debate within and beyond the ranks of Solidarity. The Labor Commission is committed to using this document as a springboard for discussions and political projects—and to revising and refining our thinking, and our political practice, based on what we learn in the process.

Teamsters battle police during the 1934 strike in Minneapolis. Read several retrospectives on the strike and its impact on the US labor movement here.

Starting Points

It is obvious that there is much to lament in the current state of affairs. In the U.S. and around the world, the neoliberal ruling class offensive is devastating the working class. The trade unions, weakened by relentless attacks and by their own political and organizational shortcomings, have failed to mount effective resistance to the ruling class agenda. Union density in the U.S. has fallen to historic lows. While the labor bureaucracy experiments with new approaches to reversing the decline in membership, most union officials will not consider initiatives that would fundamentally transform the relationship of rank and file members to their unions. In the U.S., the small Labor Left and the even smaller revolutionary Left have thus far failed to coalesce around a meaningful strategy to break out of their isolation or to take full advantage of the organizing opportunities that have arisen.

But there are glimmers of hope. In the period since the financial crisis we have seen the sporadic emergence of more determined, bottom-up campaigns and struggles. We have seen that, even in a period of retreat, militant campaigns that pose broad class demands can resonate widely. And we have seen growing recognition in the still-too-small activist layer of the working class that the traditional bureaucratic approaches are a dead end. While we do not want to overstate the positives, we nonetheless believe that they point to the potential for the development of politically independent, class-wide formations capable of offering meaningful resistance to capitalist austerity—if the Left can intervene effectively and democratically to move things in that direction.

In the first section of this document, we briefly touch upon some of the new (and not so new) and emerging struggles that are shaping working class organization and consciousness. Second, we specify some of the causes of the Left’s political paralysis in this period. In the third section we begin to pose a clear, if not comprehensive, strategy rooted in the realities of this period. Fourth, we identify some practical areas of work that we see as starting points for implementing this strategy. And finally, we address some of the political questions and challenges we expect will be raised by this new direction.

I. What’s New?

Socialists must address the following realities in any attempt to develop a relevant strategic perspective today:

- The impacts of the ruling class offensive on the structure of the working class and the daily life of workers. The U.S. working class has been restructured toward low wage, precarious, non-union work, whether in the service sector, manufacturing or logistics. Workplaces tend to be smaller and less socially cohesive, even when they are owned or effectively controlled by huge multinational corporations.

- The decline of official union structures and the weakness of rank and file organization. Union density and strength in the private sector has sharply declined, partly as a result of capital’s aggressive re-organization of the geography of production, both domestically and internationally. The public sector unions, where density remains much higher, are under attack. Teachers and health care workers, who make up a larger share of unionized workers, are now at the center of key defensive struggles. With rare exceptions such as the Chicago teachers strike, we are not seeing militant worker uprisings tied to rank-and-file revolts within the unions.

- The broad ruling class assault on the legacy of Twentieth Century working class struggle. We are witnessing a sustained and historic assault on collective bargaining, the social safety net, pensions, health care, public education, indeed all of the mechanisms that protect workers from the raw discipline of capitalist labor markets. Governments at every level have joined the employer assault by implementing austerity policies that affect the broad working-class.

- The new youth-driven movements emerging outside of formal union structures and away from the socialist Left. As demonstrated most dramatically by Occupy, younger militants are alienated from politics and the “system,” but also from unions, the socialist left, and even the idea of making demands on the capitalist state.

- The “new” forms of worker organizing with tenuous connections to official union structures. While sometimes compromised by their dependence on the labor bureaucracy, the rise of “alt-labor” groups such as non-majority unions and worker centers, and the emergence of militant movements of immigrant workers and youth, indicate the need and the potential for worker organizing that breaks with dependence on the state and traditional organizational forms. These efforts also speak to the potential to organize among groups of workers who have long been ignored by the official labor movement. In the right-to-work South, especially, necessity has given rise to valuable experiments which should be developed further, and which can provide lessons to workers in other regions.

- The new and broader forms of struggle emerging tentatively around the country. The state of working class consciousness and organization is weak and workers remain in a broadly defensive posture. At the same time, we have seen that militant resistance to austerity, organized from below and framed around broad class-wide demands, can inspire renewed working class activity, raise consciousness, and even begin to win concrete victories. We are thinking here about the emergence of movements such as Occupy and Moral Mondays, the profound nationwide impact of the Chicago teachers strike and the rise of social justice teacher unionism, the growth of the Labor Notes current, the success of the movement for universal health care in Vermont, and the election victories of Kshama Sawant and Chokwe Lumumba. These developments have all revealed an opening for the kind of broad, class-wide forms of struggle and political perspectives that are necessary in order to organize effective resistance to capital’s austerity drive.

In our view, these developments signal the need—and the potential—to put class-wide movements and organizational forms at the center of a renewed perspective on revolutionary socialist labor work. We are fully aware that the development of class-wide movements linking political and workplace struggles is more characteristic of periods of rising struggle than periods of decline, such as the present. The challenge we face is that, given the depth of capitalist restructuring, the political successes of neoliberalism, and the present relationship of forces, the narrow sectoral approach to unionism that remains dominant today has left unionized workers increasingly isolated from the broad working class, and unable to defend past gains, let alone make advances. Under these conditions, the labor movement can only build power by championing the working class as a whole—by posing its demands within a larger sociopolitical context, fighting for more universal goals (e.g. single-payer health care, livable wages), developing member self-activity, and forging genuine alliances with workers and working class organizations outside of the unions. As the debate rages about how to revive Labor, we should be clear that the only viable path forward is through rank and file struggles that consciously link the workplace and sectoral demands of union members to the needs of the entire working class.

We are proposing a more balanced approach to applying the Rank and File Strategy—one that retains our fundamental commitment to working class self-activity, develops a more politicized approach to union reform struggles, and places greater emphasis on work in broad class formations and among the unorganized working class. In order to clarify the kind of shift we are proposing, we want to take stock of those dynamics that we believe led to a narrowing of Left work in labor over an extended period dominated largely by defensive struggles.

II. Causes of Left Political Paralysis

Within the unions, recent decades have been marked by the labor bureaucracy’s concessionary retreat, the periodic eruption of one-off defensive struggles, a general absence of sustained worker militancy, and a general decline of the socialist left. This set of circumstances created very difficult conditions for the generation of socialists who went into industry in the 60s and 70s, during a period of upsurge that seemed likely to intensify. Many of these individuals subsequently played a historic role in organizing significant rank and file movements within key industrial unions, including the UAW and the Teamsters. This work continues in places, most notably with the Teamsters for a Democratic Union. The work of the comrades who went into industry in this period, and the movements they helped build, deserves a much fuller discussion, debate, and assessment than we are capable of providing in the context of this document.

It is important, however, to recognize the impact that major working class defeats have had on those efforts since the seventies. In key, standard-setting industries such as auto, top union officials met the ruling class offensive with a policy of serial surrender. By openly embracing competitiveness and class collaboration—and actively working to discipline their members to accept the employers’ never-ending demands for concessions—union officials contributed significantly to the demoralization of the rank and file. In the absence of an organized and powerful Left, the state-backed employer offensive—and the massive reorganization of the economy that has been central to it—divided workers against each other and put them squarely on the defensive.

Facing their own officials’ staunch opposition to militant, class-wide resistance, and with no social force on the horizon capable of challenging capital’s freedom to restructure on its own terms, many workers understandably shied away from militant resistance. This lack of organized resistance had a profoundly conservatizing effect. Facing a concerted employer assault enabled by the bureaucracy’s suppression of internal democracy, Left union work became heavily focused on building reform coalitions to contest local union elections on a program of union democracy and opposition to concessions, based on top-down reform, not rank and file organizing. In making this pivot, many Left union activists shifted their focus away from attempts to build independent, militant rank and file movements that could overcome the limitations of the labor bureaucracy in order to fight capital. This narrowing of focus was generally accompanied by a retreat from taking up shop floor/workplace struggles, on the one hand, and from strategizing and organizing around broader political and social questions that might disrupt electoral coalitions, on the other.

In our view, the turn away from broader political and social questions left socialists unprepared to think about how to apply the Rank and File Strategy in settings external to union reform work—in relation to the problems of the broader unorganized working class, and particularly specially oppressed groups within the class; and in relation to contexts such as organizing drives and community organizing. Now that there are fewer workers in unions and fewer Leftists in those unions, these gaps in our thinking and acting become even more problematic.

The Rank and File Strategy, with its core principle of working-class self-organization, was expressly intended to counter the tendency of unions under capitalism to pursue narrow, sectoral aims under the domination of a self-reproducing labor bureaucracy. The objective has always been to develop the capacity of the militant minority within the working class to overcome the limitations of the labor bureaucracy—not only to fight specific employers, but also to develop the unions as fighters for the whole class. Today we need a renewed socialist labor strategy, rooted in a broader, more political iteration of the rank and file perspective; one that recognizes the impact of the defeats we have endured and responds to new and emerging realities on the ground. We need to join our commitment to working class self- organization at the point of production with a broad, class-struggle, social justice unionism perspective in order to build the power we need to win defensive struggles and to lay the basis for more transformational anti-capitalist political projects

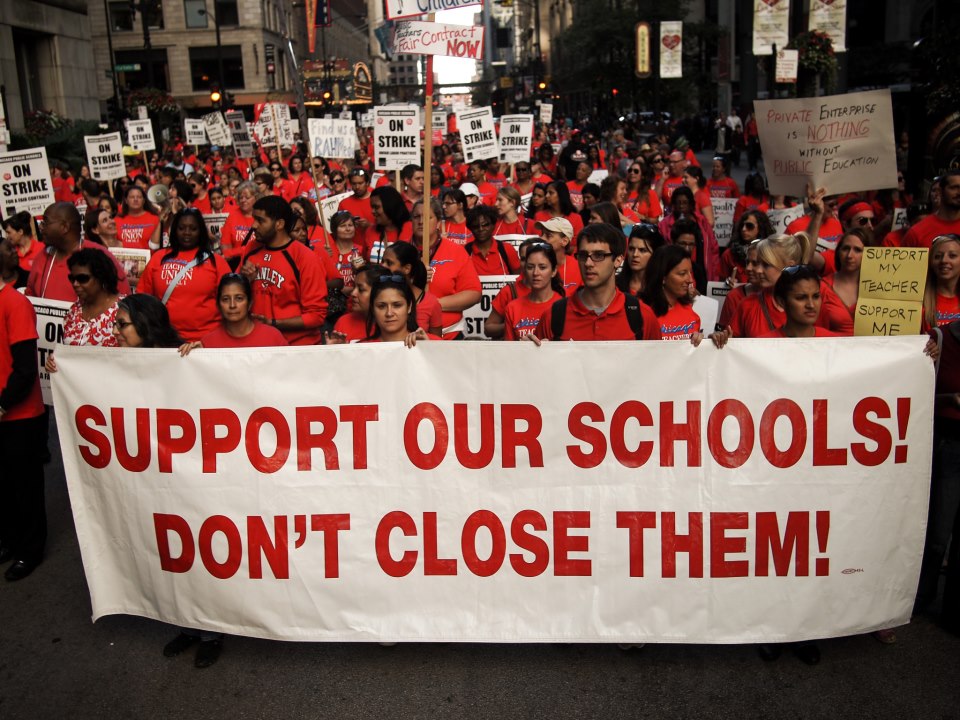

Chicago Teachers Union strike in 2012 (Photo: Sarah Jane Rhee).

III. Outline of a Renewed Strategic Perspective on Left Labor Work

The ruling class took advantage of the financial crisis and its aftermath to intensify austerity in every arena of social life, from the statehouse to the schoolhouse to the shop floor. In response, workers and working class organizations, including some rank and file caucuses and local unions, have begun to experiment with “new” ways of organizing and fighting. Some of the campaigns and struggles which have emerged out of this conjuncture reflect a new openness to the posing of class-wide demands. Others reveal a significant, but primarily tactical, shift toward community mobilization and coalition-building by more traditional officials and reformers, including the AFL-CIO and Change to Win and some of their affiliate unions. Progressive elements of the labor bureaucracy have shown a willingness to engage the vast unorganized working class—but not to disturb the rank and file’s passivity with respect to official union structures.

At their best, these campaigns and struggles combine mass militancy with demands and forms of organization that link class struggle in the workplace with class struggle in the community and begin to bridge the divide between “economic” and “political” struggles. The most advanced efforts in this direction have been bolstered by a growing number of publications, and projects that are building direct links between activists in different industries and consolidating Left activism in various communities. The most promising formations include formal or ad hoc coalitions of rank and file activists, progressive union officials, worker centers, immigrant rights groups, community organizations rooted in communities of color, environmentalists, and socialists; they project a transformative vision, at least implicitly anti- capitalist; and they do effective organizing around meaningful and concrete demands ranging from universal health care, to contract fights, environmental justice, educational justice, and immigrant rights. We believe it is these broader movements and organizational forms that will provide the primary basis for struggles that can shift the relation of forces in the coming period and provide openings for the development of a socialist current within the activist layer of the working class. In assessing what is possible in this period, we have taken note of a range of campaigns and struggles that we think can help us find a path forward.

- Occupy revealed mass opposition to the inequities of the economic and political system and rising political consciousness—though these developments remained relatively inchoate and insufficiently organized.

- The Chicago Teachers Union contract campaign and strike was framed as a broad, anti-racist community struggle against the corporate agenda for public education and for the educational needs of students. And the CTU leadership, bolstered by a militant and politically conscious reform movement, took concrete steps to insure that the union’s membership took ownership of the struggle and remained mobilized, both in the workplace and in the streets.

- Movements like the Moral Mondays campaign against austerity in North Carolina point to the potential power of coalitions united around a multi-issue, class-based, and anti- racist agenda.

- The Fight for $15 and the effort to organize Walmart workers reveal opportunities for resistance within the broad, unorganized working class – despite the limitations of the SEIU’s corporate campaign strategy and the UFCW’s failure to mobilize its own members for the Walmart campaign or for broader resistance to the employer offensive in retail.

- The emerging national student movement in higher education against skyrocketing student debt and for increased funding for public colleges and universities has received significant support from higher ed unions and formed the basis of multi-issue coalitions (e.g. ReFund California).

- The electoral victories of socialist Kshama Sawant in Seattle, and of the late Chokwe Lumumba in Jackson, Mississippi, though rooted in particular, local conditions, reflect the potential for radical movements to make use of the electoral arena to build power bases across the country.

Our intent in identifying these efforts is not to hold up them up as conclusive models for what unions and community groups should be doing to build power for the working class, but rather to highlight the valuable opportunities for socialist organizing reflected in recent attempts to mobilize workers and communities.

While it is important to highlight what is new and positive, it is equally necessary to be realistic about the moment we are living through. Notwithstanding the positive developments discussed above, we have yet to see the emergence of transformative, bottom up, class-wide struggles that challenge austerity at its core and provide a clear working class political alternative. Developing the full potential of the various campaigns, struggles and organizational initiatives emerging out of this period will require effective and democratic interventions by the Left, which is still too small and disorganized. So our tasks are twofold: (1) determining what kind of Left interventions are possible and required to radicalize and politicize these movements into transformative class-wide struggles, and (2) building a Labor Left capable of making such interventions.

To summarize, a broader strategic perspective on socialist labor work is needed that clearly articulates the following points:

- There are opportunities to advance broad, political, class-wide, anti-racist demands

attached to militant, bottom-up campaigns; - These campaigns, begun at the local level, have the potential to radicalize workers, provide political education to those in the struggle, and impact the broader political environment, as varied as that environment may be in different regions of the country;

- In this period, building such campaigns should be integrated with ongoing work in

union caucuses and other rank and file structures, allowing socialists and others to advance strategic and political perspectives that provide an alternative to top-down bureaucratic functioning by building working class power in workplaces/shop floor and communities; and - In order to develop the full potential of emerging movements we must build a Labor

Left that is rooted in the activist layer of the working class and capable of leading class-wide campaigns and movements.

This perspective suggests certain strategic priorities for socialist organizing within the working class:

- Strengthen rank and file reform movements seeking to revive unions as centers of struggle. While the union movement is at its weakest point in decades, unions are still the working class institutions with the most potential social power. At the same time, the bureaucratic nature of most unions, including many with progressive officials, has made it impossible to make this social power felt. In the few unions where leftists are in leadership, socialists should take the lead, as they are doing in Chicago, to initiate broader, struggle-oriented, political formations that link workplace/shop floor issues to a broader, anti-corporate/capitalist perspective. Whether in leadership or not, radical union caucuses should be looking to initiate such community campaigns, as Progressive Educators for Action (PEAC) is doing in Los Angeles through the Campaign for the Schools L.A. Students Deserve. The lessons of the CTU struggle can be extended to private sector union reform movements, where it is necessary to advance broad demands and forms of struggle that link the assault on unionized workers to the broader conditions of the working class. Reform caucuses that take power in unions should also be constantly mindful of the need to maintain rank-and-file mobilization and involvement in the workplace. Contract campaigns and grievance fights can be opportunities to encourage and support self-activity at the base and to raise class consciousness. Historically, the labor bureaucracy has usually encouraged passivity in the ranks in order to exalt its own importance; socialists must do the opposite, encouraging members to act in the workplace, thereby helping to develop new layers of leadership. In building these campaigns we need to look for the opportunities struggles present for relevant political debate. We need to prioritize the development of the rank and file’s skills and politics rather than merely ‘mobilizing’ to efficiently implement campaign strategies that the membership has not played a central role in developing or demanding.

- Elevate the demands of the specially oppressed within broader working class struggles. In the context of building broader class-based forms of struggle, anti-racist and anti-sexist demands and organizing must be brought to the fore, whether directed at racial profiling and incarceration, voting rights, immigrant rights, LGBTQ rights, reproductive rights, affordable child care, etc. A class-based movement in the U.S.— with its distinctive history of racism and xenophobia—can only succeed if workers recognize that they need to be advocates for all of the oppressed, dispossessed, and disenfranchised – taking up the demands of the most oppressed sections of the working class. In fact, movements of the oppressed have historically been engines of radical political development. A clear, anti-racist agenda aligned with the struggles of communities of color will raise controversies with segments of the white working class. A feminist agenda will do the same with many men. Left labor organizers have to also see the doors these efforts open to working class women and people of color often left out of labor (and left labor) leadership and the opportunities for politicizing debate they can open for all workers. Class-wide demands, such as health care for all, high quality public education, affordable housing, full employment, and a living wage are particularly relevant to the specially oppressed.

- Develop emerging localized struggles into a politically independent and militant national movement against austerity. In attempting to build locally based, multi- issue political campaigns based on bottom-up organizing, we must frankly recognize that local government has a limited capacity to fulfill our most pressing demands. We are not looking to compete with or evolve into service organizations, as have many past organizing efforts that sought to bridge the community and the workplace divide. This means that local campaigns should always be framed as part of a larger state and/or national struggle in formation. State and national efforts to build networks that link local campaigns and movements would therefore be essential.

- Advance working class organization in the South. The Left has long understood that building working class power in the South is essential to our capacity to challenge racism and shift the relation of forces nationally. Understanding the need to “organize the South” does not give us the knowledge, relationships, or forces to accomplish the task. Socialists need to further explore the potential for Left projects in the South, beginning with improving our concrete understanding of the situation. We know that, across the region, union membership is a small fraction of the workforce and unions are rarely meaningful social actors. That is a problem for the working class. But it can also open up possibilities for bottom-up organizing. And, despite the weakness of formal union structures, unions in health care, state government, and education are by far the largest working class organizations across the South. Although they are open shop, the unions with significant capacity in these states have majority memberships, and are clearly relevant to anti-austerity fights. While run bureaucratically, these unions present considerable opportunities for rank and file organizing; and there is the potential to link workplace struggles with broad class demands around public education, healthcare, and the criminal justice system.

- Serve as a bridge between movements and socialism. Building multi-issue, class- wide coalitions and movements can serve as a necessary bridge between movement- building and socialism. Building class-wide movements offers opportunities for struggle and for education about the nature of capitalism. It also offers opportunities for building militant, participatory, “pre-figurative” forms of organization—based in workplaces and communities—that can begin to address the challenge of TINA (There Is No Alternative) to capitalism by anticipating non-statist models of socialism.

- Build socialist organization. As socialists we look to the working-class, above all other social forces, not only because of its potential ability to stop production and bring capitalist society to its knees, but principally because experiences in struggling collectively for better conditions of life can generate solidarity, and develop the skills and propensities which make possible the work of building a new and higher form of society. Working-class self-emancipation requires workers to develop a conscious conception of what sort of society they are building; to be more than the “muscle” to the “brain” of a socialist organization. To make this a reality, we need more than trade unions. We need socialist organization in the labor movement, with a program around which workers can organize.

If the organized Left is to make a meaningful contribution to the fulfillment of these strategic priorities it must develop its own organizational and political capacities. Guided by a more politicized and strategic labor perspective, Left activists would have an arena for collectivizing its work, evaluating its strategic perspective, working with other socialists, and taking the necessary steps to bring a more coherent socialist perspective to its work. Crucially, broadening our understanding of the Rank and File Strategy and of what constitutes “labor work” should make it easier for the Left to adopt collective projects and sustain commitment to those projects.

Occupy protesters block an entrance to the Port of Longview in 2011 (Photo: AP/Don Ryan)

IV. Implementation

How can Solidarity and the broader revolutionary Left begin to implement such a strategy?

We have identified four broad areas of work that we see as starting points.

First, Left organizations and activists should work together to begin mapping out the local social movement possibilities. Who are the main local players? What are their politics? Would they be interested in discussing this perspective? Is it relevant to their concerns and challenges? Would any union caucuses be interested in discussing a broader perspective for their project? What kinds of political education would serve as tools for framing the struggle, bridging workplace and social demands, and support the nuts and bolts work of organizing?

Second, Left organizations and activists need to begin building a network of Left labor and social movement activists committed to elaborating and implementing a common strategy. The work involved will exceed the capacity of any particular existing organization or political tendency. For such a network to come together there would need to be an intense national discussion of strategy, and the development of a framework/ toolkit for regional discussions. Articles should be written for Left and progressive publications that reach a broader audience, including Labor Notes. Left activists should convene workshops, conferences, etc., to develop these and other ideas ideas more fully and explore practical applications where possible.

Third, to further Left collaboration, Left activists should work together to find private and public sector jobs with the greatest potential for organizing around class-wide demands. In the private sector, such jobs, including food services, hotels, and logistics, are prime locations for organizing political fights for the right to work with dignity: livable wages, paid sick leave, the health care that we need, and other benefits for low-wage workers. In the public sector, public education and health care are highly unionized and offer opportunities to advocate for class-wide demands such as quality public education and health care for all as an integral part of a rank-and-file union strategy. Further, concentrated, focused Left work in all these sectors would provide an avenue for socialists to advance the leadership role of women and people of color within the working class.

V. Questions and Challenges

We will no doubt face a number of practical and political questions as we attempt to bring this strategic perspective to life. To conclude, we attempt to address, briefly, just three of those questions that we believe will be important going forward.

What kind of programmatic demands make sense in this period? The Left needs to guard against “programitis”—the tendency to promote unrealistic, often class-wide demands within the movement as opposed to immediate demands of struggle. At the same time, the Left must also resist the tendency to “tail” movements with weak strategies or demands so as not to appear sectarian. While there is no formula for what program or demands may be appropriate at any given time, we should always be looking for opportunities to frame all immediate reform struggles in a broader anti-capitalist context. Figuring out how to think about program and demands requires that socialists be both deeply embedded in the movements and in political dialogue with the most advanced leaders in those movements.

How can we advance a consistent “from below”/self-activity approach to movement building? In this period, with the exception of Occupy, we are not seeing working class movements and struggles develop “spontaneously,” (without being initiated by an organization, union, etc.). In many cases, the initiating organizations are bureaucratic unions with a tactical and often temporary need to both initiate and control a broader struggle. Too often, then, such struggles are led by top-down, staff-led coalitions that offer little space for mass participation and discussion. As such, we generally advocate for democratic coalitions and organizations that provide for individual membership and participation, and, to the extent possible, for mass organizations with a democratic and accountable leadership. In the current period, multi-issue coalitions and campaigns will be joined, if not led, by various kinds of organizations, some with paid staff. How to fully involve such organizations and at the same time advance the development of working class self-activity will be another challenge that can only be resolved on the ground.

How can we use this strategy to drive a renewal of revolutionary socialist organization through recruitment and regroupment? In recent decades, the revolutionary Left in the U.S. has failed to attract many of the best militants and organic working class leaders. This has to change. The most powerful way to convince activists that “another world is possible”—and necessary, given the socially and environmentally destructive trajectory of capitalism—is to raise the prospect of organized working-class power, beginning at the local level, and ultimately linked together by a state and national program. This strategic perspective looks toward the day when activists begin to confront—in practice—key questions about capitalism, the state, revolution and socialism. To get to that point, and prepare ourselves for it, we need to develop a broad program of socialist education as well as new mechanisms and organizational forms for collectively and democratically thinking through the challenges faced by our movements. Solidarity and other Left forces can take modest steps in this direction now with strategy discussions and educational programs that seek to involve the most committed activists and organizers in our milieu. Where possible, we should seek to bring the broader revolutionary Left together in these efforts.

Comments

2 responses to “A Renewed Strategic Perspective on Socialist Work in the Labor Movement”

I think that this document is useful and thoughtful. In reading it, though, I had a few reservations.

In “Implementation,” it suggests the Left activists should seek certain kinds of jobs. Not present in that list was anything about the freight or related industries. This raises the question of how we should relate to TDU. I would think that it remains a potential center for left strength and organizing, and a source of potential solidarity and power for other activities. Have I missed something? If this is NOT true, then I think it would be useful to discuss why it is not true, and what that implies for the future.

In Section V. Questions and Challenges, I am concerned about the lack of attention to the climate crisis and the movements around it. On the one hand, this crisis is enormous and has to be addressed. On the other, it seems to me to be a perfect area for Left labor activists to take on important politics and show why the working class is so crucial. What I have in mind is that the climate crisis takes concrete forms in local disasters. As things stand, neither capital nor governments are very good at dealing with the after-effects of such disasters (and often do not want to). We saw this with both Katrina and Sandy–and we saw that Occupy Sandy did excellent work, and helped draw attention to the left in this regard. In the case of Katrina, some sections of the left and of the working class likewise sent aid. (I wrote a poem about this and can send it on to anyone who asks.)

Wouldn’t it make sense for our local left and labor groups to plan ahead on how to respond to various emergencies? And how to build political organization in the communities where we do this? This is not the same as “social service work,” and it can be politically very meaningful for the local communities.

A very interesting and thoughtful document.

I would add that a key weakness facing the socialist left today is the absence of a credible and readily understandable outline of how socialism would work.

I don’t think this requires a detailed blue-print. But it does require some basic propositions that sound realistic, workable and achievable.

Too often, in my experience, when asked what socialism would involve, some socialists reply with dream-like scenarios of a conflict-free world of super-abundance and hyper-democracy.

Instead we need a vision that makes clear how socialism would create a practical social dynamic more conducive to solving certain key problems (those relating to climate change and poverty) without lapsing into child-like wishful thinking.

Such a vision must be able to provide us with credible answers to common objections.

For example, if we talk about workplace democracy, then how do we counter the criticism that such a system would be impractical?

If workplace A votes in a way that is inconsistent with the policy adopted by workplace B (perhaps resulting in A not receiving the quantity and quality of inputs it needs to meet a socially determined target) then what happens? Is democracy suspended? By whom and by what means? Will agreement always be possible? Really?

Will the broad social imperative to tackle poverty begin to erode worker control of production at the level of the office and the factory, with the performance of work increasingly decided by higher bodies of government? If so, what would the implications be for skill, the use of workplace technology, and overall human development?

In my experience these are questions that are not only raised by opponents of socialism. I have had discussions with union activists about these issues. Some firmly believe that some form of capitalist division of labour is unavoidable and that democracy in a modern workplace is a nice idea but impractical.

In general, we need a vision of socialism that is credible to those we want to mobilise in support of a different society. In the past, Communists pointed to the Soviet Union. Some Trotskyists also invoked the USSR – for economic, if not political, inspiration (although the distinction was never valid).

We don’t have a concrete example to point to. And platitudes, clichés and wishful thinking won’t cut it.

So mobilisation, while important, is unlikely to be sufficient when it comes to re-building the socialist movement. We need to know more about what we are fighting for and how it may actually work.