Fred Glass

Posted November 23, 2020

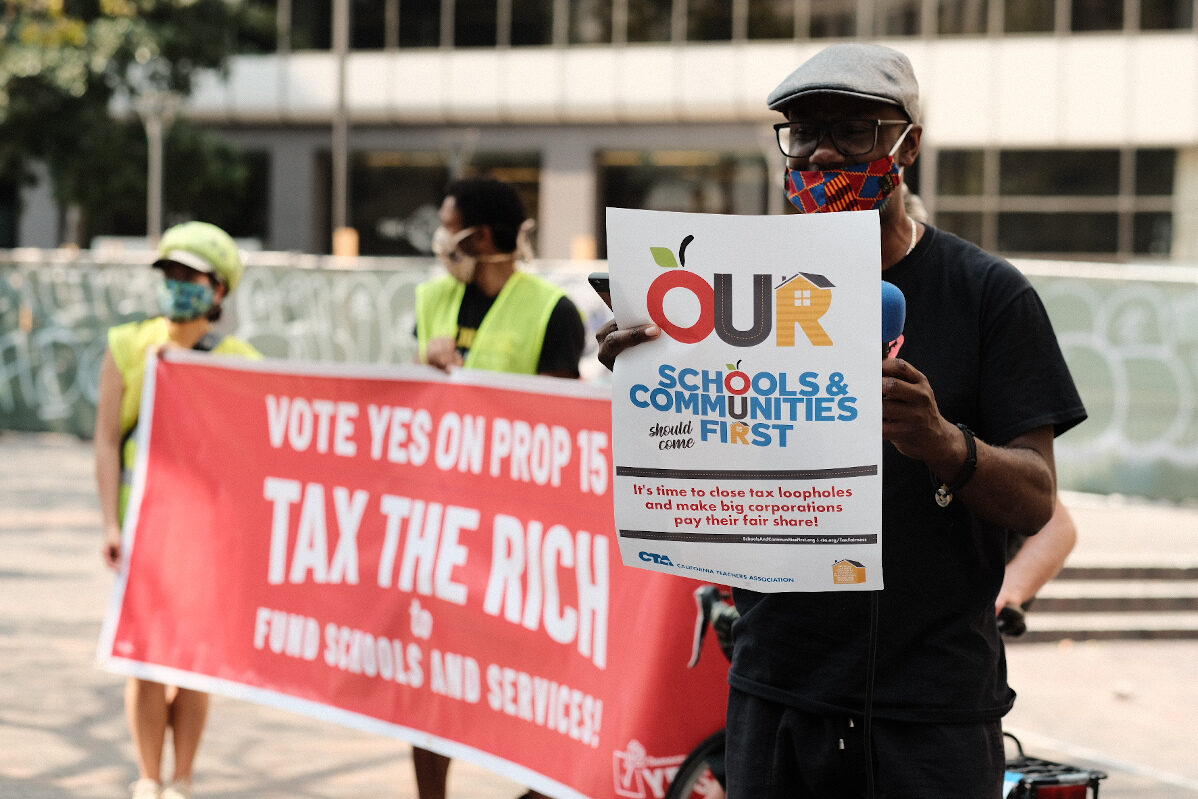

Prop 15, an ambitious ballot measure to increase taxes on large commercial property, was top priority for both the California labor movement and progressive community organizations and the Chamber of Commerce. When the dust settled, the Chamber could savor its success in robbing billions of dollars from school children, the hungry, the sick, workers who rely on public transportation, communities who live in the path of the next firestorms, and elders and toddlers in daycare facilities.

It accomplished this important goal by bundling $38 million from real estate, property management and private equity firms, alongside a like amount from other sources in the more reactionary sectors of the capitalist class of California. This opposition ultimately outspent the pro-Prop 15 forces by some $20 million, fueling an onslaught of false but effective messages to three slices of the electorate: homeowners, small businesses and African Americans. It received help from the Governor of California, who despite endorsing the measure, didn’t lift a finger to campaign for it; and from two effects of the pandemic: the inability of Prop 15 forces to muster the grassroots volunteer “people power” that traditionally counterbalances big money in an election campaign; and voters’ economic fears, magnified by the pandemic Depression.

An Anti-Austerity Coalition

Prop 15, known as “Schools and Communities First,” represented the outcome of a decade-long effort by a progressive tax coalition to craft and bring before the electorate a split-roll ballot measure, separating commercial from residential properties for purposes of tax assessment and revenues. Ever since passage of the notorious Prop 13 of 1978, a landmark early blow in the neoliberal assault that transformed the post-World War II order into the new normal of austerity, the state’s left, broadly considered, has understood that it eventually had to take on at least one of Prop 13’s several nasty provisions: the assessment of commercial property based on purchase price — no matter how long ago it last changed hands or how much it had appreciated in value since — rather than current market value, on the basis of which most states levy property taxes.

For older large commercial property-owning corporations like Disney and Chevron, the stakes were high. Prop 15 would have raised $10 – 12 billion dollars annually in non-pandemic years, a substantial increase of five or six per cent to the state’s $200 billion budget. Chevron alone would have been on the hook for an estimated $50 – 100 million yearly bump. Since the Prop 15 coalition shrewdly provided exemption for commercial properties worth less than $3 million, along with excluding all residential properties, the measure was expected to gain 92% of its revenue from just 10% of the state’s richest properties. If not entirely a game changer for schools (slated to receive 40% of the funding stream, with local services pegged at 60%) it would have helped raise per pupil spending and maybe allow teachers to find classroom supply budgets in their school rather than their own back pockets.

Instead, the coalition of public sector unions and community organizations fell short, 52 to 48 per cent.

Despite the loss, some positive lessons for socialist electoral work can be drawn from the campaign. I will detail here the activities of my local DSA chapter and a network of California DSA chapters pulled together expressly to participate in the campaign. I’ll conclude with a few general observations about this work and its potential to play a more formative role in similar campaigns in the future.

East Bay DSA

East Bay DSA and DSA-LA were the first two chapters to endorse Prop 15. Participation in the campaign offered an opportunity for the many new activists in DSA to develop their organizing skills and to gain experience working with labor unions as well as social movement groups. , East Bay DSA formed a working group in May, and we outlined a broad schedule of work in three phases: internal education in the summer, outreach to the electorate by late August or early September, and Get Out the Vote (GOTV) activities in October.

State Working Group

The East Bay DSA plan was more or less adopted by the state DSA working group, which formed its own Prop 15 subcommittee by July. Some discussion occurred in both groups about how to relate to the official campaign. A number of participants were active in their public sector unions, and through that route were plugged in from the beginning to meetings and trainings related to the coalition. We found ourselves pretty much in agreement that the messaging from the campaign was principled enough in its approach to the politics of inequality (“corporations and wealthy individual property owners need to pay their fair share of taxes to support schools and services”) but, depending on who we were talking to — starting with our own members — could use a more direct message, i.e., “tax the rich for schools and services.”

Those of us who attended the trainings reported back that while the campaign messaging was softer, it was flexible in that organizations in the coalition were expected to tailor their conversations with their own constituencies based on greater knowledge of their members. We agreed to just go ahead with our “tax the rich” message, rather than worrying that coalition “message discipline” would prevent us from doing so. As things turned out, with minor exceptions, there was no conflict over messaging.

We were clear that our major activity in the latter stages would have to be phone banking, given the pandemic, but at the outset left the question open as to whether we would run our own phone banks, join with the official campaign’s, or call voters through the phone banks of the unions we belonged to. In the event, we participated in all three.

Activities

Our first activity, after passing chapter endorsement resolutions, was a series of three educational seminars held on ZOOM. The first provided an overview of tax policy basics from the early twentieth century through the present. The second was a history of public sector unions in relationship to tax policy, since they invariably either led the charge or played a major role in progressive tax campaigns. The third focused on the nuts and bolts of Prop 15 itself, with Rudy Gonzalez, executive director of the San Francisco Labor Council, and Cecily Myart-Cruz, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, presenting their organizations’ plans for the campaign. These sessions were held in late June and early July.

Following the initial educational phase, we began outreach to our own members, chapter by chapter. This took the form of internal phone banking, continuing to share the educational seminar series, (which had been recorded and posted on You Tube), pointing to articles, and presentations at chapter meetings. We were blessed with the talents of artist Paul Zappia, a member of the LA chapter, who designed some gorgeous graphics, created ready-to-print poster art, and produced a spectacularly good “explainer” video on Prop 15.

In the East Bay our working group met weekly and soon formed three subcommittees to organize phone banking, house meetings, and external public events. The internal phone banking went well in August, but did not reach our goal of talking to everyone; we got about halfway there, and then relied on email blasts and text messaging to contact those whom we hadn’t reached by phone.

The house meeting committee held several events, based on a relational organizing model of outreach to friends, family and workmates, but given the size of the chapter membership, and despite numerous solicitations via zoom meetings, emails and text banking, did not achieve the scale we had hoped for.

Outdoor actions

The public events committee put together two outside actions, meant to reach as many people as possible during the event itself and then amplify the audience through social media networks and commercial mass media attention. Our first, a car caravan, was planned for Labor Day, and working with the state group, six chapters took part: East Bay, LA, Inland Empire, Santa Barbara, Ventura, and Davis. The smallest chapters, Santa Barbara and Ventura, pooled their resources and held their event together. In the East Bay, Trent Willis (president, ILWU Local 10), and Keith Brown (president, Oakland Education Association), as well as a couple Oakland School Board candidates, spoke at the start of the car caravan at Oakland Technical High School. Everyone wore masks and stayed socially distant.

Once downtown, the caravan, seventy-five cars strong, circled the block containing the Oakland Chamber of Commerce. In front of the building, Liz Ortega-Toro (Executive Secretary Treasurer, Alameda Labor Council) and school board candidate Van Cedric Williams decried the selfishness of the Chamber and large commercial property owners who were fighting to keep money in their pockets that rightfully belonged to underfunded public schools and local services. As at Oakland Tech, their speeches were broadcast on a low power FM channel run out of one of the cars, and the caravaners were able to listen to commentary as they drove slowly through the streets of Oakland past examples of the property tax inequities Prop 15 was meant to address.

Just one TV truck showed up, but with a pool reporter, which meant he shared his footage with several stations that ended up airing stories. It helped that the Labor Council, due to the pandemic, had planned no Labor Day event, traditional kickoff for labor’s electoral effort, and so we had the media field to ourselves.

The other event came a month later on October 9, when the same chapters staged simultaneous banner drops on freeway overpasses during rush hour. Tens of thousands of cars across the state saw the message “Tax the rich for schools and services, Yes on Prop 15” and the arm waving, masked campaigners that held the banners for a couple hours. The event roused no mainstream media interest this time, but the participants felt it was all worthwhile due the many solidarity honks they received.

The purpose of these outdoor events was to help establish a sense of a mass movement from below supporting Prop 15, an element important in previous successful tax the rich campaigns in California, but mostly missing this time around during the pandemic.

After this we focused on phone banking. The Los Angeles chapter took the lead, putting in place a program, coordinated with our other chapters, to call voter lists supplied by the official campaign. The centerpiece was the “15 for 15” phone bank, which featured inspirational speakers and brief training sessions via zoom before calling voters each night for fifteen nights in the second half of October. By election day California DSA members had made more than 300,000 calls — a greater number than many unions in the coalition.

Campaign communications

It is a truism within the world of state ballot campaign communications that the No side has an easier time of it: you don’t have to win on the merits of the arguments as much as sow suspicion and plant seeds of doubt about the Yes position. This is especially the case when the No campaign, as is invariably the case for the right wing, feels no compunction whatsoever about lying. These were the central messages of the other side:

“First they are coming for commercial property, then they are coming for your homes.”

Prop 15 explicitly exempted residential property of all kinds — homeowners, landlords and renters alike were not to be touched. Even worse, other messaging on this theme actually said that homeowners would be directly hit by Prop 15.

“Small businesses will be ruined.”

Prop 15 exempted all commercial property below $3 million in value, and provided a tax cut on business equipment that mostly benefited small businesses.

“Commercial property owners will pass along the increases to their clients, and the clients will pass them along to the public.”

Markets are not dependent on property taxes for what their participants charge, either in commercial rents or in a multitude of direct sale businesses. Property taxes, even with a bump up to market rates on commercial property, are a minuscule portion of any business’s expenses.

“The last thing we need during a pandemic Depression is more taxes.”

By “more taxes” the opposition was falsely implying “taxes on everyone.” Prop 15 proposed a specific tax on a relative few specific people. 92% of the revenues generated from Prop 15 would have come from just 10% of the properties in the state — in other words, large corporate property owners.

In addition, direct mail targeting Black voters came early and in waves, with an endorsement by the California state NAACP for the “No” position, claiming the measure was going to hurt people of color. Its president, Alice Huffman, is a political consultant whose firm accepted nearly three quarters of a million dollars to work on behalf of the No campaign. While legal, barely, her dual role conflict of interest was decried by more progressive African American voices like local NAACP chapter officer and DSA member Carroll Fife and Anthony Thigpenn, the leader of California Calls, a community organization dedicated to outreach and activation of low propensity working class voters and an important coalition driver. But the damage was real among Black voters and never reversed. [Note: On November 20 Huffman announced her retirement from the NAACP presidency, citing health reasons, after a firestorm of protest within the organization.]

These messages no doubt might have been more effectively countered if we had been able to run a field campaign, the benefits of which extend far beyond the obvious importance of knocking on doors and holding rallies. Word of mouth for a big coalition of grassroots organizations is crucial, especially when the other side outspends you on media. The pandemic meant we could not meet directly with people in the pathways of daily life as per usual in non pandemic times. PTA meetings in predominantly African American schools; unionized workplaces and churches in communities of color; grocery stores and sidewalks; these are the places in which daily contact with trusted personal connections can and often do overcome the doubts and suspicions planted by the other side: “Did you see that mailer from the NAACP. What was that about?” These granular conversations, in the hundreds of thousands in a state the size of California, could not and did not happen this time around due to COVID 19.

Despite these problems, the margin was close enough that we still could have won were it not for the late and tepid endorsement of the Yes on 15 campaign by Governor Gavin Newsom. In 2012 then-Governor Jerry Brown campaigned hard for Prop 30, drawing tremendous attention on the evening news to the measure and its compelling argument. That income tax bump on the top 2% richest Californians to fund the public sector won 55-45. The earned media that Yes on 15 missed out on due to the lack of public events, exacerbated by a Governor who was nowhere to be seen, might well have countered the advantage in paid advertising money held by the other side.

The official campaign

The coalition hired competent managers familiar with the recent progressive tax campaigns in California and solid staffing to coordinate the voter education and GOTV efforts. It pulled together an active speakers bureau, training hundreds of union and community activists on the Prop 15 message points. A number of DSAers attended the training and were duly assigned to speaking appearances on zoom (I spoke, for instance, to the student Democratic club at UC Berkeley, several unions, and the Rotary Club of Alameda County) and dispatched to send letters to the editor to every possible publication.

Although outspent $80 million to $60 million, the Yes budget — the bulk of which came from the California Teachers Association, SEIU and odd bedfellow Chan Zuckerberg Initiative — was substantial enough to closely compete. The messaging seemed fundamentally sound, although apparently not effective enough around specific targets of the other side (homeowners, African Americans, small business owners) outlined above.

Thus a number of tactical decisions of the campaign could be scrutinized as to how effectively it utilized the resources it had. Window signs were printed late, and no lawn signs were made. I saw dozens of makeshift lawn signs created by enterprising partisans who stapled two of the smaller, flimsier window signs in a sandwich around a stake. When I did the same, a rainstorm melted it.

When DSA members in San Francisco doing literature drops door to door for a comrade and candidate for state senate, Jackie Fielder, offered to carry Prop 15 flyers at the same time, the campaign’s response was to steer them to the Prop 15 website, where they could print out a generic flyer. When the DSAers noted they had no printing facilities or budget but were offering the work of dozens of precinct walkers to hit thousands of dwellings, the response was a shrug.

More significantly — and this is speculation, but informed by my decades of work as a union communications director sitting at communications tables of campaign coalitions like this one — the central message probably should have been sharper. “Corporations need to pay their fair share of taxes for schools and local services,” or “close corporate tax loopholes” are both fine upstanding progressive slogans. But in our phone banking and on our banners DSA pushed a bit harder with “Tax the rich,” a message not fully embraced by the campaign — although some other coalition partners, like the California Labor Federation, went there in its mailers to union members.

Messaging for ballot measures is not a science, although some of the consultants who design opinion research would have you believe so. What you ask and how you ask it determines the answers. The frames for the phone surveys and focus groups are not typically constructed by socialists, so class resentment is often not tested very deeply or even at all.

In the midst of a Pandemic Depression during which 165 individuals in California — one quarter of the nation’s billionaires — watched their bank accounts increase by several hundred billion dollars (a figure greater than the entire state budget) at the same time that millions of people were forced onto unemployment, thousands have died, and the state budget was expected to find itself with a $50 billion hole blown in it due to pandemic-related tax revenue losses, it might have made sense to utilize these monstrous factoids to whip up resentments at the ballot box. Economic inequality, a problem visible to all since the Great Recession, was woven in various ways throughout the Yes campaign’s messaging, but in the background, in response messaging, not with the clarity of the billionaire example in combination with the simplicity of “tax the rich for schools and services.”

It might be argued that a split roll tax campaign is not the same as a tax the rich campaign. It is not an income tax that directly extracts tax from income; and it is not as clearly a tax on the wealthy as say an inheritance tax. But if we are going to go with the message, repeated ad nauseam by the campaign, that 92% of the revenues generated by Prop 15 was to have come from 10% of the commercial properties in the state, what is this but an indirect way of saying we are taxing the rich? And that’s the problem: it’s indirect and therefore less effective.

A few conclusions

DSA made a significant contribution to the Yes on 15 campaign. For the first time in three quarters of a century, the socialist left is considered enough of a player that it was embraced — albeit unevenly and with some reservations — by labor and an official ballot campaign that in the Cold War past might have accepted that help sub rosa or outright rejected it. Due to its hard work, pre-pandemic, on various local elections, support for strikes and the Bernie campaigns, California DSA chapters were seen in 2020 by local labor councils and unions as helpful allies with convergent interests and values, and its members as reliable foot soldiers for the cause. DSA activists’ willingness to conduct outdoor events in the time of COVID helped build a public profile for the campaign, and its phone banking numbers were impressive by any calculation.

Going forward, California DSA members working on similar campaigns will have a stronger understanding of the issues based on the Prop 15 experience; be able to more quickly develop effective strategies and tactics; and should continue to be welcomed by the labor community as useful partners. As a result of our work on Prop 15, for instance, we formed a state DSA political action committee, and purchased, with the assistance of national DSA, our own dialer for phone banks.

Despite the trite proclamations of pundits that the sacred “third rail” status of Prop 13 has been validated, nothing of the kind has been determined. This should not be the end of the road for a split roll tax in California. The need has not gone away, the progressive tax coalition is not going away, and we did not lose by much. A prediction: following some sober reflection on the particulars of this election, and recalling that we won progressive tax victories in 2012 and 2016 before losing in the unique situation of 2020, next time we will win.

Fred Glass, a member of East Bay DSA, is the former communications director for the California Federation of Teachers, and author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (University of California Press, 2016).

Comments

6 responses to “Prop 15 goes down as big corporations shaft the people of California”

If we try again, the tax should be phased in over several years. Harder to complain about it then. Easy to complain about having to come up with hundreds of thousands of $$s with 4 months notice. And perhaps agriculture should get some special dispensation, since we count on it for food and farmers do not get paid sufficiently for their products to be typical “rolling-in-the-dough” corporate types. The Farm Bureau mounted a HUGE campaign against Prop 15. And indeed, it would have put quite a few farmers out of business. They are on a knife edge already.

Dear Fred

Thank you for sharing your important and informative article. So what is gonna happen? Will it ever be possible to reverse Prop 13?

Will it be back on the ballot in 2022?

all the best

Ray

Now I know why I never took your class, Fred. Reading assignments on a holiday weekend?

Nonetheless, an excellent report and analysis/assessment. As much as I hate excuses on electoral losses, a pandemic is the best I can think of. As you say, it shut down our best tactic – talking to our people in multiple ways.

I agree that with somewhat sharper messaging and no virus, this is very winnable and even more necessary. I just wish we didn’t have to wait another four years.

Dear Fred, I count on you to keep me up on the struggles and provide a way to keep safe while protesting in support of our students and schools. Thanks Fred for your report on the stealing of Prop 15, a critically important and fair way to provide desperately needed funding.