by Johanna Brenner

August 22, 2014

This article was originally published in Socialist Studies: The Journal of the Society for Socialist Studies. This is the first half of the article; the second half will be published separately.

Looking back to the heady days of feminism’s “second wave”1 in the United States, it is distressing to acknowledge that the movement’s revolutionary moment is a dim memory, while key aspects of liberal feminism have been incorporated into the ruling class agenda. Liberal feminist ideas have been mobilized to support a range of neo-liberal initiatives including austerity, imperial war, and structural adjustment. For example:

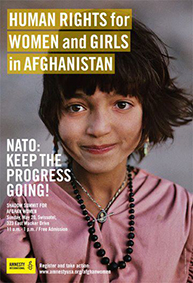

Amnesty International flyer implicitly supporting the Afghanistan War on the basis of women’s rights.

Austerity: Welfare reform essentially ended income support for solo mothers even of very young children and forced them into low-waged work. This shift was justified as an intervention providing women with jobs and therefore “economic independence.”

Imperial War: The US government used the liberation of women as cover for the invasion of Afghanistan and ties the “war on terrorism” (e.g. in Pakistan) to freeing women from patriarchal control.

Structural Adjustment: World Bank micro-credit loan programs targeted to women are a neo-liberal substitute for government-subsidized anti-poverty programs. Micro-credit is touted as a route to women’s empowerment and economic independence through entrepreneurship.

Surely it is important to understand how it came to pass that feminist ideas have been so firmly incorporated into the neo-liberal order. But some recent explanations offered by feminist scholars point us in an unfortunate direction.2 These writers argue that second wave feminism, with its overemphasis on legal rights and paid work as a route to equality, unwittingly paved the way for neo-liberalism. It is comforting to think that feminism had this level of control over the outcome of our struggles. For, were it true, we could now correct our mistakes, change our ideas, and regain our revolutionary footing.

I want to make a different argument. Liberal feminism’s partial incorporation into the neo-liberal economic, political, cultural and social order is better explained by the emergence of a regime of capital accumulation that has fundamentally restructured economies in both the global north and the global south. In the global north, this new regime was ushered in by the employers’ assault on the working class, on the welfare state, and on the historic institutions of working class defense ― unions and social democratic parties. This assault set the political context for the successful backlash against the radical equality demands of feminists, anti-racist activists, indigenous peoples and others and the rise of neo-liberalism.

While the new regime of capitalist accumulation in the first instance extinguished the radical promise of the “second wave,” it is also creating the material basis for the renewal and spread of socialist-feminist movements led by women of the working classes — and I mean working classes in the broadest sense — whether they are women employed in the formal economy, the informal economy, in the country-side or doing unwaged labor. The political discourses and movement building through which socialist feminism is being enacted in the 21st century are a resource for the left that everywhere is struggling to find its feet. People have a sense that the old forms of left politics will not do. In this search for alternatives, socialist-feminist strategies have much to offer.

20th Century Feminism

To understand what happened to feminism, we need a class analysis. I mean class in two senses: 1) class as capitalist relations of production, the dynamics of the capitalist economy ― its logic so to speak; 2) class as one of many important axes of domination ― of unequal distributions of power and privilege ― around which capitalist societies are structured.

As a Marxist feminist, when I think about capitalist relations of production, I am also drawing on the concept of social reproduction. All societies have to organize the labor involved in maintaining and renewing the population ― Marxist feminists term this social reproduction and we focus on this theoretical concept because the work of social reproduction is fundamental to human survival. Social reproduction includes caring labor but also includes how sexuality is organized — not only because of biological reproduction but because intimacy and desire are mobilized in and through institutions that organize social reproduction―in capitalism, for example, the privatized, nuclear family household.

Thinking about class in the second sense, I draw on the concept of intersectionality. In feminist theory intersectionality has emerged as an analytic strategy to address the interrelation of multiple, cross-cutting institutionalized power relations.3 Here class is just one axis of power among others including race, gender, sexuality, citizenship status, ability, and so forth. Most intersectional analysis draws on the concept of social location, a “place” defined by these intersecting axes of domination, and asks how a social location shapes experience and identity.4 I use the concept of survival projects to express the connection between intersectional social locations and social action, including but not limited to political activism. I like the idea of survival projects because a) survival, in the broadest Marxist sense, asserts that there is a materiality to social action, b) project implies intentionality and rationality but also projects are open-ended―and that makes room for praxis―the possibilities for self-change that inheres in collective action; and c) projects indicate motivation and drive―and allow us to think about the ways in which social action, including collective action, mobilizes emotions and affect.

In conceptualizing the relationship between social location and social action, I also draw on the Black feminist thought of Patricia Hill Collins. In analyzing how Black women negotiate their specific social locations she distinguishes between resistance within the constraints of these locations ― within the rules of the game, so to speak — and resistance that aims to change those rules.5 When I talk about class as a relation of power and privilege similar to gender or race/ethnicity I’m going to use the concept of the professional/managerial class ― a contradictory class location that shares, at its upper end, conditions of life close to those who own and control the means of production and, at its lower end, conditions of life much closer to those of the working-class (and I acknowledge the fuzziness of this boundary).

So, back to the story: what, after all, did happen to 20th century feminism in the US?

The dominant feminist political discourse in the “second wave” was not classic liberal feminism — that is, a feminism that wanted to clear away any impediments to women’s exercise of their individual rights ― but rather what I would call social-welfare feminism. (Outside the US where there were actual left parties and where socialist political discourses were more available to feminist activists, this politics could be called social-democratic feminism). Social welfare feminists share liberal feminism’s commitment to individual rights and equal opportunity, but go much further. They look to an expansive and activist state to address the problems of working women, to ease the burden of the double day, to improve women’s and especially mothers’ position on the labor market, to provide public services that socialize the labor of care and to expand social responsibility for care (e.g., through paid parenting leave, stipends for women caring for disabled family members).

Women in the affluent end of the professional/managerial class are the social base of classic liberal feminism. Social welfare feminist politics finds its social base predominantly in the lower reaches of the professional managerial class and especially women employed in education, social services, and health. Professional/managerial women of color are more likely to be employed in these industries than in the private sector. Women trade-union activists also played a significant part in leading and organizing social-welfare feminism.

We can generously characterize as ambivalent the relationships between working-class women/poor women and the middle-class professional women whose jobs it is to uplift and regulate those who come to be defined as problematic ― the poor, the unhealthy, the culturally unfit, the sexually deviant, the ill-educated. These class tensions bleed into feminist politics, as middle-class feminist advocates claim to represent working-class women. The way these class tensions get expressed is shaped considerably by other dimensions of class locations such as race/ethnicity, sexuality, nationality, ability. The politics of middle-class feminists also shift depending on the levels of militancy, self-organization, and political strength of women in the working classes.

A compelling instance of this dynamic can be seen in the first half of the 1970s. In the political context of the Black struggle for economic justice, driven by the Black working class, and the welfare rights movement that was the civil rights movement’s working-class feminist leading edge, social welfare feminists took up a visionary and broad-based program of expanding state support for caring labor. For example, in 1971, a coalition of feminist and civil rights organizations won the Comprehensive Childcare Act (CCA) that would have established day care as a federally funded developmental service available to every child who needed it. Although no doubt feminists saw this legislation to be crucial to mothers’ employment, they did not limit the benefit only to mothers working for pay. The program included provisions for medical, nutritional, and educational services for children from infancy to fourteen years of age. Services were to be on a sliding fee scale. President Nixon vetoed the bill, but organizing around it continued throughout the 1970’s.

In this historical moment, the politics through which social-welfare feminism fought for socializing the labor of care drew on ideas of the National Welfare Rights Organization, which reflected the social location of its core activists ― poor black women. What is most interesting about the NWRO’s political discourses is their capacity to creatively combine claims that philosophers, lawyers, and academics tend to see as competing. I have in mind here the distinction between “needs talk” and “rights talk”.6 Maternalist political discourses are quintessential examples of “needs talk.” Here, advocates make claims based on children’s needs and mothers’ unique capacity to fulfill those needs. On the other hand, the demand for gender-blind employment practices or equal access to professional schooling is quintessential “rights talk,” demanding individual rights for women that are already granted to men.

The emerging Black feminism of the NWRO activists rejected this “either/or” counter-position of different strategies for claims-making. Johnnie Tillmon, the charismatic leader of the welfare rights movement, published a ground-breaking article in Ms. magazine (1972) where she compared being on welfare to marriage ― women on welfare, she said, were “married to the state” and, like wives, were economically dependent and disempowered. The condition for receiving assistance was to allow government institutions to control your sexuality, your household and your parenting. The NWRO argued for a program of guaranteed, that is unconditional, minimum income for single mothers. Poor women should have choices about how they parented and they, themselves, were the only appropriate authorities to establish their children’s needs. They should receive economic support and social services whether they were stay home mothers or working parents. The welfare rights activists critiqued the employment programs that were part of the federally-funded war on poverty where single mothers were channeled into training for traditionally female, low paid, pink color jobs. Finally, they linked their demand that motherhood be recognized as valuable work to women’s economic autonomy and their right to self-determination.7

This “both/and” politics was reflected also in women of color’s challenge to the pro-choice movement. Where the radical and liberal wings of the feminist movement focused on women’s rights to bodily autonomy ― and the right to refuse motherhood ― women of color were facing a very different assault ― forced sterilization of poor women in public hospitals where they gave birth. Further, the welfare rights movement was organizing poor women and especially black women, to challenge the denigration of their motherhood and the stigmatization of their sexuality. Taking up the ideas of working-class women of color activists, socialist-feminists in the anti-capitalist left articulated a politics of reproductive rights that reached beyond the language of choice. Reproductive rights included the right to be mothers, to raise our children in dignity and health, in safe neighborhoods, with adequate income and shelter. Reproductive rights is a program of non-reformist reform– some of these demands can be fought for and won under capitalism–for example, to outlaw racist sterilization abuse or discrimination against lesbian mothers―but the full program of reproductive justice is incompatible with capitalism. In this respect, reproductive rights political discourses bridge feminism to anti-capitalist politics. In the U.S. today, Sister Song, a coalition of forty women of color groups animated by a program of what they term reproductive justice, exemplifies this politics and has had some success in pushing the mainstream pro-choice organizations to broaden their political agenda.

At its height, second-wave feminism argued for socializing the labor of care. Shifting care from an individual to a social responsibility required then and requires today a redistribution of wealth from capital to labor. Social responsibility for care depends on the expansion of public goods which in turn depends on taxing wealth or profits.8 Compensating workers for time spent in caregiving (e.g., paid parenting leave), expands paid compensation at the expense of profits. In addition, requiring (either by regulation or by contract) that workplaces accommodate and subsidize employees’ caregiving outside of work interferes with employers’ control over the workplace and tends to be resisted in the private sector where jobs continue to be organized as if workers had very little responsibility for care. In other words, to socialize the labor of care requires confronting capitalist class power. And it was here that 20th c. social welfare feminism foundered. To confront capitalist class power required a broad, militant, disruptive social movement ― an anti-capitalist front linking feminism, anti-racism, gay rights, and immigrant rights to trade unions and workers’ struggles. What existed instead were bureaucratic, sclerotic, sectoralist trade unions that had neither the interest in nor capacity for building movements of any kind.

Almost at the very moment of social-welfare feminisms greatest strength, in the 1970’s, the tsunami of capitalist restructuring arrived, opening up a new era of assault on a working class that had no means of defending itself. As people scrambled to survive in this new world order, as collective capacities and solidarities moved out of reach, as competition and insecurity ratcheted up, as individualistic survival projects became the order of the day, the door was opened for neo-liberal political ideas to gain hegemony. Caught between a demobilized working-class and a Democratic party overtaken by neo-liberalism, middle-class social welfare feminists began to accommodate to the existing political realities. For example, leaving behind the “both/and” politics of the NWRO, middle-class advocates moved away from the maternalist discourses ― e.g. “young children need to be with their mothers” ― that, however problematic, had been part of their defense of income support to single mothers. And they moved toward neo-liberal discourses of “self-sufficiency” in the face of a fierce bi-partisan critique of the welfare system for encouraging “dependency.” They embraced the idea of “self-sufficiency” through paid work, even though it was quite obvious that the low-paid precarious jobs open to so many single mothers would never pay a living wage, that the childcare stipends provided (to the poorest women) were inadequate for quality childcare, and that after-school programs for older children were unaffordable.9 In other words, second-wave social welfare feminism was not so much coopted as it was politically marginalized. And in the context of that defeat, not surprisingly, liberal feminist politics not only moved center stage but became incorporated into an increasingly hegemonic neo-liberal capitalist regime.

Ironically, as middle-class advocates moved rightward, working-class feminists, especially in unions with large or majority women members, were making substantial gains. They increased women’s representation in leadership, pushed their unions to support political mobilizations defending legalized abortion (CLUW’s “pro-union, pro-choice” campaign) and opposing discrimination against LGBT people, and placed demands like comparable worth and paid parental leave onto the bargaining agenda. However, these latter gains rang hollow, as unions lost ground so swiftly, including at the bargaining table.10

Feminism and other movements against oppression will be cross-class movements and therefore pose the question, “who will have hegemony within those movements?” Whose worldviews will determine what the movement demands, how those demands are articulated and justified, and how the movement itself is organized? In the ordinary course of events, the answer to these questions is the middle-class. Yet, as in the moment of the second wave’s greatest radicalization, when working-class people walk onto the political stage, the power relations within social movements can shift.

Johanna Brenner is a community activist in Portland, OR and an advisory editor of Against the Current. She is Professor Emeritus at Portland State University.

Footnotes

- I use this term as a shorthand for the feminist organizing that emerged in the mid-1960’s and reached its height in terms of reach, multiplicity of points of view and radicalization in the 1970’s. I specify my meaning of the term in order to acknowledge the many very good critiques of the “wave” metaphor, its historical inaccuracies, and its exclusions.

- See Hester Eisenstein, Feminism Seduced: How Global Elites Use Women’s Labor and Ideas to Exploit the World, and Nancy Fraser, “Feminism, Capitalism and the Cunning of History.” For a critique of Fraser’s perspective, see Joan Sangster and Meg Luxton, “Feminism, Co-optation and the Problems of Amnesia.”

- This concept first emerged in the 1970’s from the practice and theorizing of revolutionary Black feminists―see,for example, the Combahee River Collective statement―and was further developed by women of color feminist theorists including Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, Angela Davis, Cherie Moraga, Andrea Smith, Patricia Hill Collins and Kimberle Crenshaw. Although “intersectionality” is, unfortunately, more often invoked than actually practiced, fully incorporating all of the axes of power/privilege in our political analysis and action remains feminisms’ central task.

- See for example Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought, and Dorothy Smith, Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for the People.

- Ibid, chapter 5.

- See Nancy Fraser, “Talking About Needs: Interpretive Contests as Political Conflicts in Welfare-State Societies,” and Barbara Hobson and Ruth Lister, “Citizenship,” in Contested Concepts in Gender and Social Politics.

- See Guida West, The National Welfare Right Movement: The Social Protest of Poor Women and Premilla Nadasen, Rethinking the Welfare Rights Movement.

- Capitalist welfare states have expanded primarily through taxing salaries and wages rather than wealth and profits; however, there are distinct economic and political limits to this strategy for funding public goods.

- For a more nuanced analysis than is possible here, see Johanna Brenner, Women and the Politics of Class, Chs. 5 & 6.

- On working-class women’s feminism in the U.S., see Dorothy Sue Cobble, The Other Women’s Movement: Workplace Justice and Social Rights in Modern America. For Canada, see Linda Briskin and Lyda Yanz, Union Sisters: Women in the Labour Movement, and Meg Luxton, “Feminism as a Class Act: Working Class Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Canada.”