by Bob Rossi

April 24, 2014

On March 30 Turkey held local and regional elections. The dominant narrative has been that the elections were a victory for Prime Minister Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP). In fact, conservative forces have nothing to crow about. The elections forced the government to show its worst side and gave the left and the Kurdish liberation movement some openings.

Prime Minister Erdogan.

In the run-up to the elections Erdogan and his party had to deal with fall-out from on-going investigations into possible coup attempts and this severely weakened the military leadership. A probe into widespread bribery and graft reached deep into Turkey’s elite families and the political structure. With this probe the Gulen movement broke with the AKP and thousands of people employed in the Turkish bureaucracies and police forces were either fired or transferred, causing chaos. Business leaders grew nervous and the economy slowed. Mass mobilizations picked up where last year’s Gezi (June) resistance left off. The government met these new conditions with repression. Police actions were brutal, the media was intimidated and most social media was shut down just prior to the elections.

Since the rise of the Gezi resistance last year the AKP-led government has not had many options. This was Gezi’s short-term victory. The government has either had to move towards a more repressive model or surrender its right-populist terrain. In choosing the former it has temporarily alienated many of its strongest allies.

The Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), a left Kurdish party, and the People’s Democracy Party (HDP), an alliance of left parties, went into coalition last fall. This alliance gives progressive Kurds an opportunity to make their case to Turkish people and gives the Turkish left a stronger platform. The Turkish Communist Party (TKP) also crafted a united front. The BDP-HDP alliance prioritized running women and men together so that both candidates could be elected to fill one position. It also prioritized labor, feminist, LGBTQ and environmentalist candidates and supported at least one Armenian and one Assyrian candidate. The BDP won 55% of the vote in Amed/Diyarbakir, 4 LGBTQ-friendly candidates won (results are disputed) and an unprecedented number of women were elected from the three main parliamentary parties. The TKP won one position in Dersim, a majority-Alevi region with a history of dramatic political struggles. The Alevi minority experiences particular oppression and leans to the left. Alevis provide great intellectual leadership to progressive movements

The BDP-HDP alliance could not have come into being without the Gezi resistance, the more militant struggles at Ankara’s Middle East Technical University, the feminist movement and political turns taken by the Kurdish liberation movement. A high price has been paid by these forces recently: scores of members and leaders of the Public Employees Union Confederation (KESK) have been imprisoned for political and union work, over 225 Gezi resisters were indicted, over 200 Kurdish freedom fighters are facing trial and every major protest organized over the winter was either banned or attacked by police. In the aftermath of the elections the government criminalized “platforms,” the attempt by labor and social movements to form alliances beyond their constituencies. Violence from the government and the far-right preceding the elections took a toll on the left and center. Post-election violence took the lives of at least 10 people. Abdullah Ocalan, the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), and other militant Kurdish leaders could have done more and better to help in this situation and the BDP made certain tactical mistakes. Still, the BDP-HDP alliance won over 4% of the nationwide vote.

The Republican People’s Party (CHP) took big losses. The CHP is the heir of Turkey’s founding republican struggle and is the oldest party in parliament. It won almost 28% of the vote on a weak social-democratic platform and with lackluster candidates. Both the CHP and the BDP-HDP can rightly claim that the AKP and the nationalist-fascist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) engaged in vote rigging and violence, but the CHP seems to have surrendered its outrage at these events while the BDP-HDP continues to organize. Nationalism runs in varying shades from the MHP to the CHP and into the TKP. The AKP got about 46% of the vote and the MHP took about 16% of the vote.

An AKP deputy and a CHP deputy fight it out in parliament.

Why did the AKP win? Turkey is a conservative country experiencing many contradictions. Twelve years of AKP rule have brought periods of economic growth which has alarmed the US and the EU. Turkey has reoriented toward the Gulf and Arab states in order to offset this interference. The Turkish intelligence service opened negotiations with Ocalan and relative peace now prevails. The Turkish government interferes in Syria and attempts to broker relations between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and the government in Baghdad with the upshot being that Erdogan is seen as a regional leader and Turkish industry has a reliable supply of oil. Erdogan successfully played off US and Chinese interests in a recent missile deal and has an on-again-off-again relationship with the EU and so has some international standing. The Gulen movement and the AKP worked together in strengthening the middle-class and the movement’s assimilationist policies bribed some Kurds to move rightward. The AKP also used anti-semitism. Turkey is both an imperialist power and a victim of imperialism.

What does the AKP win mean in the immediate future? In the aftermath of the elections Erdogan promised revenge on his opponents. His first target is the judiciary. The economic gap between Turkey’s urban and rural areas will continue to widen, women are increasingly being excluded from the labor market, overall wages have begun to stagnate and North Kurdistan is being left behind. Religious women at the AKP base will feel increasingly alienated from the party. Erdogan may have postponed, but not stopped, an economic crisis which will hit small businesses and the banking sector which function without interest payments. We can expect a resumption of peace talks between the government and Kurdish forces. The PKK will continue to grow, the BDP-HDP will consolidate their gains and social movements will remain relatively strong. Leaders of two union federations are seeking peace with the government and the employers while KESK and DISK, the two progressive labor centers, are continuing to struggle against repression and fight for women’s rights, reform of the educational system and limiting child labor. Both unions have recently engaged in politicized general strikes. The Kosova textile workers in Istanbul won when they occupied their factory last year and worker occupations are taking place at the American-owned Grief burlap sack factory in Istanbul, an electric company in Amed and at newspaper offices in Ankara and Istanbul.

One context for all of this is that US and EU policies towards Turkey are somewhat different. After a brief period of distance, the US will recalibrate relations with Erdogan while the EU will move at a slower pace. The EU does not want a stronger Turkey. Presidential elections will be held in August and the next general election will be heldin 2015. Erdogan is termed-out as Prime Minister but may either push to hold the position or may run for president; either option will be divisive. Turkey has no tradition of social democracy and the CHP remains hopelessly old-school. If the BDP-HDP alliance holds, if the Kurdish struggle maintains its momentum and if the Gulen movement does not reunite with the AKP the left may do better in 2015. Overt interference from the US could provoke a coup or a situation in which the ultra-right leads an armed struggle against the left and the Kurds as it did in the 1970s.

The Revolution in Rojava

Kurds live in Iraq (Kurdistan, or the KRG), Turkey (North Kurdistan), Syria (Rojava) and in East Kurdistan (Rojhelat and Iran). A majority of Kurds are Sunni Muslims but Kurds also follow Shi’a Islam, Alevism, Yazidism, Zoroastrianism and Christianity. A Kurdish Jewish community lives in Israel. The Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) has companion parties with fighting forces in Rojava and Rojhelat. The revolution in Rojava is especially advanced.

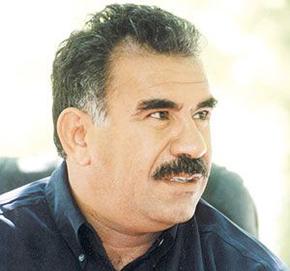

Abdullah Ocalan.

Abdullah Ocalan of the PKK has worked from prison to shift the ideology of the Kurdish liberation movement in new directions. Ocalan and his followers have adopted core feminist ideas as well as the principles of “democratic confederalism” or “democratic self-management” and they advance these as alternatives to the nation-state. They reject urbanization, centralism and the idea of the unitary state. A majority of PKK guerillas are probably women and the PKK has prominent women in leading positions. Beze Hozat, one of these leaders, emphasizes the PKK’s role as a Middle Eastern liberation movement and as a social system. These ideas are sometimes described as “broadly Marxist” or anarchistic.

Rojava borders much of southern Turkey and all of North Kurdistan. The revolution has created three self-managed cantons which have federated and which have the legal right to federate with other regions. Each canton has governing councils and assemblies. A Social Agreement unites the cantons into a federal system and provides that “The development of production and the aim of economic activity are to meet human needs and establish an honorable life…The ownership of the national means of production shall be established; the rights of citizens, workers and the environment shall be protected; and national sovereignty consolidated.” The leading party in Rojava is the Democratic Union Party, a PKK ally. About four million people live in Rojava, with three languages and seven national groups recognized.

Rojava is taking an independent path as the civil war in Syria continues. Rojava got an early boost when Bashar al-Assad signaled that government forces would not attack the region. The primary enemies of the revolution are the Al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria. The Turkish government has backed Islamist forces against Rojava and fighting is bloody and costly. The revolution has sometimes cooperated with the Free Syrian Army in its own defense but also acted to protect the Kurdish community in Aleppo. The cantons have the People’s Defense Forces and the Women’s Defense Units to defend them. Women have two combat battalions and a military training institute.

The leadership of the KRG has sought to isolate the revolution by building fences and digging trenches at its borders, by siding with Erdogan in Turkey and by working for a centralized Kurdish state under their leadership. Refugees flee to Rojava while people from there also seek to flee the fighting, creating a chaotic situation and a burden on the revolution. The KRG’s stance is inhumane.

The revolution has developed an extraordinary system of advancing women and young people through autonomous organizations. The Union of Free Women has led in these efforts. The People’s Council and the Union in one of the canton’s recently hosted a 22-day training academy entitled “Towards building a democratic assemblies vanguard of women.” This was the 15th such academy held in Rojava. In developing an economic plan for Rojava people have often adopted cooperative models and have created an officially recognized microeconomy to enable women’s economic advancement. Rojava also recently hosted a conference on democratizing Islam. Special efforts at bringing the Arab minority into the revolution have met with mixed success.

Rojava sought to send representatives to the Geneva “peace talks” but the imperialist powers rejected them. Representatives then went before the Swedish and Norwegian parliaments with some success. Practical support comes from Kurdish communities in Europe and the PKK and its companion parties. The BDP-HDP and much of the Turkish left also do much to assist. International support has come from the FARC in Columbia, Irish Republicans, Basque revolutionaries and from Tamils.

Bob Rossi publishes Harvest, a newsletter supporting revolutionary, democratic and progressive forces in Turkey, North Kurdistan and Rojava.