by Dan La Botz

January 13, 2014

The Chiapas Rebellion led by the Zapatistas took place twenty years ago this month. What was the importance of the rebellion and of the Zapatistas? What was the impact at the time? And what has been its political legacy? What is the role of the Zapatistas in Mexico today?

Twenty years ago, on the morning of January 1, 1994, the Chiapas Rebellion began in Mexico’s southernmost state led by a then unknown group, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and its mysterious spokesman subcomandante Marcos. Some 3,000 poorly armed, mostly Mayan guerrilla soldiers marched out of the jungles and seized a half dozen towns and briefly took the city of San Cristóbal de Las Casas. The EZLN had chosen January 1 because on that day in that year the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), an international treaty between Canada, Mexico, and the United States, took effect. The EZLN rebels called for the cancellation of NAFTA, the overthrow of the government of Mexican government, and the convocation of a constituent assembly to write a new Mexican constitution. Some of the guerrilla troops told reporters they were fighting for socialism.

The Chiapas Rebellion had an enormous impact at the time, not only in Mexico but around the world. The EZLN had led the first leftist, armed rebellion since the fall of Communism and the break-up of the Soviet Union just a few years before, suggesting that contrary to claims about the death of the left and the “end of history,” a new left had arisen in the Lacandón Jungle of Chiapas. The rebellion also signaled that all was not well in Mexico, where outgoing president Carlos Salinas had been claiming that by joining the GATT, forerunner of the World Trade Organization, in 1980 and by joining NAFTA, and through his privatization of hundreds of state companies, Mexico was leaving the Third World and entering the First World of modern capitalism. The Chiapas Rebellion and the EZLN Manifestos pulled back the veil revealing to the world Mexico’s world of rural poverty and especially the poverty oppression of the indigenous people.

President Ernesto Zedillo, who had taken office only a month before, responded immediately by sending the Mexican army and air force to suppress the rebellion. Throughout Mexico tens of thousands of people responded by going to the zócalos, the public squares, to protest, demanding that Zedillo stop the military attack on mostly Mayan rebels. Within twelve days Zedillo halted the attack and the EZLN agreed to a truce, the beginning of what has been a twenty-year standoff in Chiapas.

When several months later the Zapatistas held a consulta, a kind of survey or referendum, asking what role they should place in Mexican society, hundreds of thousands responded, the majority voting that the EZLN should lay down its arms and participate in Mexican social and political life. The initial protests against Zedillo’s use of the army and the results of the consulta suggest that the Mexican people rejected armed violence on all sides. In the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920, one million had died and one million had emigrated in a nation with a total population then of 13 million. The memory of revolutionary and counter-revolutionary violence seemed to live on in the public consciousness and apparently few wanted to repeat that experience.

Armed revolution in Mexico it seemed was not on the agenda. The Zapatistas declined to lay down their arms, but on the other hand, for the last twenty years, neither have they used them. The EZLN’s continuing struggle took other forms.

Who Were the Zapatistas?

The Zapatistas were founded in November of 1983 by a group of leftist activists in northern Mexico. The Mexican left had inherited a long tradition of armed rebellion, one could say going back to the conquest, though certainly the Mexican Revolution’s nationalist legacy was most significant. In addition there was the impact of the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s foco theory (which has been popularized by the French intellectual Régis Debray) and which had had such disastrous consequences throughout Latin America.

Throughout Mexico in the 1970s and into the 1980s one could find small rural and urban guerrilla groups, some calling themselves Marxist-Leninist and usually combining a left wing version of Mexican nationalism with Cuban foco theory ideas or sometimes with Maoist ideas of a prolonged people’s war. Hundreds of such young men and women were disappeared and murdered during Mexico’s secret war in the 1970s. The Zapatistas had their origins in that political milieu. Initially called the National Liberation Forces, a name that became popular on the left in various countries after the Algerian revolution, the group later, after moving to Chiapas, added “Zapatista” to their name after Emiliano Zapata, the leader of the revolutionary peasant movement during the Mexican Revolution.

Later in the 1980s the group decided to move its operations to Chiapas in southern Mexico, a state with a very large indigenous population made up of several different Mayan groups. As in the rest of Mexico at the time, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) controlled government at all levels and controlled the labor and peasant unions and various indigenous organizations. There was, however, a developing social alternative. Since 1959 the Bishop of Chiapas had been Samuel Ruíz, who had participated in Vatican II (1962-1965) and in the Latin American Bishops’ Medellín Conference (1968) and who was completely involved and identified with the Theology of Liberation, the idea that the Church should be on the side of the poor.

Under Ruíz’s direction the Catholic Church in Chiapas took an interest not only in the salvation of the souls of the indigenous, but also in improving their material conditions and their social and political treatment. The Church’s catechists became not only carriers of the Gospel but also organizers of the indigenous people’s incipient social movements. It was in this milieu that the Zapatistas now inserted themselves, and with Ruíz’s tacit support, often worked closely with the catechists and other indigenous leaders. Ruíz said that while he shared the Zapatistas’ goals he did not support their strategy of armed rebellion, yet at the same time he did not prevent the EZLN from organizing. So during almost a decade the Zapatistas established their organization in Chiapas, recruited Mayan and mestizo activists to their organization, and laid their plans for an armed uprising.

What Did the Zapatistas Believe?

What did the Zapatistas have in mind when they revolted on January 1, 1994? The Zapatistas apparently believed that if they ignited a spark in southern Mexico it would unleash a wildfire across the entire country. Whether or not they were familiar with the concept or the term, this is very like the nineteenth century anarchist notion of the “propaganda of the deed” and also bears a resemblance to the foco idea of the dedicated revolutionaries in the sierra who will ignite a revolution in the plains. The idea is that the people, exploited and oppressed, are simply waiting for a heroic example of revolutionary struggle to show them the way, and that then they will rise up and overthrow capitalism. The Mexican people, as was demonstrated in the early months of 1994, were not prepared to follow the Zapatistas or to rise up, and while millions sympathized with the poverty and indignities suffered by the indigenous, they rejected the idea of armed struggle. Mexico was no different than any other country where social change tends to come not from heroic actions of a few but from years of organization, education and propaganda, and many concerted smaller actions at the base of society before people are prepared for revolutionary change.

In August of 1994 the Zapatistas called a convention in their jungle redoubt to which they invited some 2,000 Mexican intellectuals, writers and artists, academics, and social movement activists, as well as a few official delegates from the United States of whom I was one. Once in San Cristóbal we traveled to the convention on public buses donated by the state government and attended the ceremony where the stage was lit by stadium lights which must also have been provided by the state and the Federal Electricity Commission. Marcos spoke before an enormous Mexican flag, perhaps 40 by 20 feet, as the Zapatista soldiers (some wearing boots but most in huaraches and a few barefoot) marched before the platform, most carrying wooden rifles, not real firearms. The huge flag and Marco’s rhetoric suggested that the EZLN were radical nationalists and advocates of indigenous rights; while there was a call for a constituent assembly to write a new constitution, there was no talk of socialism. Really, this was not a convention, just a few speeches until the event ended in a tropical downpour of Biblical proportions that put out the lights and swept away our tents. The EZLN’s politics were still in evolution.

The Zapatistas failure in launching a revolution and the Mexican army’s siege of the zone in which they operated forced them to retreat and fall back on the indigenous and other poor people in the canyons where they had their base. The Zapatistas now did more openly what they had been doing clandestinely for years, organizing their indigenous and mestizo supporters into communities that constituted a kind of liberated zone—though interspersed with other indigenous and mestizo communities that did not support them and surrounded by the army which sometimes harassed them.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s the Zapatistas organized remarkable protests by indigenous women who came out in their traje, their indigenous dress, and literally pushed the armed soldiers out of their villages. The EZLN called indigenous meeting in Chiapas and inspired the convocation of national indigenous meetings that led to the creation of the National Indigenous Congress. After months of negotiation, on Feb. 16, 1996, the Zapatistas and the government of President Ernesto Zedillo signed the San Andrés Accords, a treaty granting autonomy, recognition, and rights to the Mayan people in Chiapas. The Mexican Congress, however, didn’t adopt the accords, and the Zedillo government soon violated them. The Zapatistas announced they wouldn’t therefore hold any further negotiations, withdrawing again into the canyons.

The Zapatistas and their supporters claimed that they had created new democratic forms of organization in the villages in which women had an equal role. Marcos and other EZLN spokespersons argued that they were reconstituting society from the bottom up a village at a time. Eschewing the state institutions controlled by the PRI, the Zapatistas created their own schools and local governments—though they had few if any economic resources—as an alternative to government institutions. Marcos and the Zapatistas began to develop a new rhetoric and to proclaim a new ideology summed up in the phrase “mandar obedeciendo,” to lead by following. This suggested that the people were deciding and the leaders merely expressing their views and carrying out their desires. Here it was suggested was the socialism from below that many of us believed in and had been working for.

In the late ’90s lawyer and sociologist John Holloway popularized and elaborated on the Zapatistas’ ideas, and his book Zapatista! Reinventing Revolution in Mexico became a best seller on the left. He suggested that, in part under the influence of indigenous ideas, the EZLN had rejected the old Marxist paradigm of the proletariat struggling for state power, putting on the agenda a new theory and practice of revolution that seemed to have more in common with anarchism: anyone from any social class could begin to make the revolution by asserting their dignity and forming a liberated community where they were. The Zapatistas seemed to be building such a communitarian alternative to capitalism in the remote communities in Chiapas.

Yet it was very hard for outsiders to see and to understand exactly what was really taking place in villages in the canyons of Chiapas where a group of armed men were working among the native people. The continued existence of the EZLN as an armed guerrilla group alongside and among indigenous people led one to ask: How democratic was the movement? How were decisions really made? Who were the real leaders? The Zapatistas and their supporters offered answers that had to be taken on largely on faith given—at least for most of us—the impossibility of entering physically, intellectually, and psychologically into the world of indigenous politics in Chiapas.

The Zapatistas, as interpreted by Holloway and others, had an enormous impact on the new Global Justice Movement that began in the 1990s and culminated at the Battle of Seattle, the joint environmental-labor protests against the WTO in 1999. Everywhere young people wore the balaclavas and red bandanas of the Zapatistas over their faces, often identifying themselves with anarchism. Every major city and many colleges in the United States had Zapatista support groups. Mexican American youth of the Southwest were particularly inspired by the Zapatistas. The combination of the romance of masked men and women, of armed struggle, and of the utopian idea of an immediate march to an egalitarian future held sway throughout the decade, inspiring many young people to become activists. Then it was all suddenly extinguished along with the Global Justice Movement by the September 11, 2001 attack on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon by Islamic fundamentalist terrorists, and by the War on Iraq, leading to a sudden rightward shift, new levels of government surveillance and repression, and an instantaneous upsurge in American patriotism. Other armed fighters now held the public attention.

The Zapatistas and the Movement

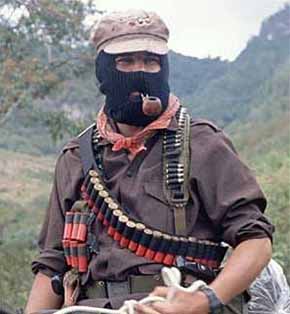

Subcomandante Marcos.

In Mexico during the first couple of years after the rebellion the Zapatistas had enormous moral authority. Much of Mexican society admired the Zapatistas for their courage and for speaking out with and for the indigenous. Many were charmed by subcomandante Marcos’ sardonic wit and great creativity both as a speaker and a writer. Mexican youth from the wealthy neighborhoods of Mexico City to the poorest neighborhoods of the border towns adopted a new Zapatista swagger as they painted radical graffiti on the walls. The Zapatistas attempted to capitalize on their moral authority by projecting themselves as a force in the broader Mexican society.

Living in Mexico in those years, I attended in Mexico City and in Tijuana meetings of the Zapatista Front for National Liberation (FZLN) which held a founding of the national organization in 1997. The Zapatistas, however, seemed to have no interest in a real front, that is, in a coalition of various left organizations and movements. EZLN leaders found difficult the give and take of coalition building in a country where there were scores of social movements, labor unions, and left political parties. The EZLN’s insistence on dominating the supposed front that they had created meant that it never grew or became popular and never had an impact in Mexican society at large.

The EZLN also attempted at about the same time, with the aid of leftists in the labor movement, to organize a Zapatista workers’ organization. The labor union activists I knew and with whom I spoke told me that the Zapatistas opposed participation in the existing labor unions, not only because they believed they were bureaucratic, but also in part because the unions held elections and the EZLN didn’t believe in elections and voting. With an unwillingness to deal with the unions and their existing structures and with longstanding rank-and-file labor organizations, the Zapatista labor organization was stillborn. The Zapatistas’ attempt to turn themselves into a political force in Mexican society failed utterly, and they withdrew again to the canyons of Chiapas.

The Zapatistas were more successful in Chiapas and in some other areas in organizing their autonomous municipalities which they called Caracoles y Juntas de Buen Gobierno. While almost all of these communities were in Chiapas, the Zapatistas did inspire some in other states and in the Plan Realidad Tijuana of 2003 proposed to unite the archipelago of liberated communities in Mexico into one emerging free nation within the nation. Though the plan never proved successful nationally, the Zapatistas did continue to organize their own autonomous communities in Chiapas.

The EZLN and the National Elections

When the 2000 elections approached, the EZLN announced that it would not support either of the two rightwing parties—the National Action Party (PAN) and the Institutional Revolutionary Party—nor would they support the leftwing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) led by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas. Cárdenas, who had been a presidential candidate in 1988 and 1994, remained enormously popular on the left. Many hoped that the Zapatistas would support him, though organizations of the revolutionary left were divided over the issue of whether to support Cárdenas or back some independent socialist candidate. The EZLN, however, rejected elections in general and Marcos excoriated Mexico’s political parties of all stripes as compromised and corrupt.

Yet the election proved not to be irrelevant to the Zapatistas. When Vicente Fox of the PAN won the election by a large plurality and became president, ending the PRI’s more than seven decade hold on government, the Zapatistas decided to take advantage of what was apparently a new political opening. The Zapatistas traveled to Mexico City and its representatives, in an historic act, actually spoke to the Mexican Congress, asking that it fulfill the principles embodied in the San Andrés Accords. While Fox showed some sympathy with the EZLN, nothing new was forthcoming from the Mexican Congress.

“The Other Campaign”

In 2006 when the next presidential elections took place, Marcos and EZLN adopted a different approach. Once again, most of the Mexican left hoped that the EZLN would support the left candidate, Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the PRD, who was speaking out strongly against NAFTA, neoliberalism, and the corruption of the PRI and PAN. The EZLN, still rejecting both elections and the existing parties, had other plans. Marcos announced the organization of la Otra Campaña (the Other Campaign). Unlike other political parties, the EZLN would not put forward its own candidates and would not support the candidates of other parties, but would instead organize a campaign that would travel around the country speaking out against the Mexican government and against capitalism.

The EZLN’s Other Campaign was joined by several other left groups, from the Trotskyist Revolutionary Workers Party (PRT) to the followers of Albanian Enver Hoxa in the Communist Party Marxist-Leninist (CPML). The Campaign took place during a period of a number of dramatic social conflicts, most important the civil unrest in Sal Salvador Atenco in the State of Mexico. When police suppressed flower sellers and other street vendors, the Peoples Front for the Defense of the Land called upon the EZLN for support. Marcos and EZLN showed up bringing thousands of supporters. During the Other Campaign, Marcos and other speakers held moderately successful meetings and rallies around the country, sometimes speaking to thousands against the evils of capitalism. Everywhere they went, the CPML’s giant portraits of Stalin hung in the background, casting doubt in some minds about the meaning of it all.

Meanwhile the PRD’s left candidate López Obrador harangued crowds of up to a million, mostly working class and poor people, with his populist rhetoric. When it became clear that President Fox and the ruling PAN party were violating election law and preparing an enormous fraud, which in fact took place on election day in July, there arose an enormous protest movement in defense of a fair election and citizens’ right to have their votes counted. Tens and perhaps hundreds of thousands in Mexico City joined the protests blocking the boulevards and occupying public plazas.

Several of the revolutionary left groups involved in the Other Campaign went off to join the election protests as a matter of principle; even if they hadn’t liked the parties and candidates offered up in the election they felt the citizens had the right to vote and have their vote counted. Marcos and the EZLN, opposed on principle to elections, refused to participate in the defense-of-the-vote protests. So they withdrew and retired to Chiapas. The Zapatistas sectarian attitude toward that movement did enormous damage to their reputation among those in the broad left and those on the far left. They lost much of the moral authority that had clung to them since the 1994 uprising.

Questions Posed for the Left and for the EZLN

During the last twenty years, the Zapatistas have had a huge impact on Mexican society and on the left both in Mexico and internationally. When the left seemed moribund, they revived it. Where the indigenous had been downtrodden, they were inspired to rise up. Their example enthused radicals throughout the Americas and in Europe and at their international meetings in the Chiapas jungle one could find leftists from dozens of countries exchanging experiences and perspectives. In retrospect, it is surprising that no organized international tendency, no “new international” came out of it. Despite all of the vicissitudes of their twenty-year long career, the Zapatistas remain both a local social movement in Chiapas and the standard bearers of a certain radical politics in Mexico associated with local organizing, support for the indigenous, and political abstentionism.

The Zapatistas’ experience raises important questions for the left. There is no doubt that in a capitalist system and its liberal democratic state, as it is called, in which political parties operate, elections function primarily to both buttress the system and to regularly place representatives of capitalism in power. It is also true, however, that elections by parties which are genuinely independent provide an opportunity for the left to propagandize for its ideas and to use elected positions to contribute to the organization of social movements.

The Zapatistas are right that the Party of the Democratic Revolution and its candidates Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and López Obrador were representatives of social democratic and populist variants of capitalist politics. The PRI, the PAN, and the PRD have all proven to be quite corrupt, it is true. But what if the Zapatistas had used the enormous moral authority that they had in the first years after the rebellion to help to organize—not to insist on controlling—a national social movement and a genuinely independent national political party? How much greater could their impact have been during these last two decades in which, partly under the impact of the NAFTA treaty that they opposed, the power of Mexican capital has grown so much greater and the forces of working people become so much weaker?

To me, the Zapatistas remain opaque and their politics mysterious. I wonder: Does there still exist at the core of the EZLN a hardened cadre who hold to the classical guerrilla politics of the 1970s and 1980s—or did the Zapatistas under the influence of the indigenous and their own experiences really become some sort of anarchists? What is the real nature and significance of the Caracoles y Juntas de Buen Gobierno? Can the Zapatistas ever overcome their sectarianism and project themselves as an ideological and organizing force in Mexican society—or will they continue to cut themselves from other sections of the far left?

After twenty years the Zapatistas have not gone away, remaining a challenge to both the government and to the established political parties and the parties of the revolutionary left. The new and deeper integration of Mexico into the U.S. and global economies which has been achieved by the passage of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s structural reforms will raise new challenges and very likely produce new movements. We will see in this new period whether or not the EZLN’s experiences and ideas prove relevant to a new generation of radicals.

Dan La Botz is a member of Solidarity in New York City, and an editor of New Politics.

Comments

4 responses to “Twenty Years Since the Chiapas Rebellion: The Zapatistas, Their Politics, and Their Impact”

I read this article today, July 20, 2016, and the commentary, because I was wondering what had become of the Zapatistas. I didn’t know if the organization still existed. The article provided a historical account of the EZLN up to 2014 and I’m grateful to have this information. It is unfortunate that the EZLN did not reach out to help the people of Oaxaca. And aligning with a blatantly communistic group that proudly displayed the image of Stalin was anathema to most of the rest of the world especially the U.S. and me too. I believe in economic and political change, but not change in which some one assumes absolute power and rules by fear. There’s more than enough of that in the world today. I hold in my heart all groups that are eager to create caring communities that ensures justice and resources for all. The Zapatistas seem to be that for the indigenous of Chiapas.

Great article.

Congratulations to Dan La Botz on the publication of his important assessment of the neo-Zapatista experience [Twenty Years Since the Chiapas Rebellion: The Zapatistas, Their Politics, and Their Impact]. It will help to redress the imbalances brought on by a lot of super adulatory coverage on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the neo-Zapatista insurgency and also the contrary conservative condemnation of this movement displayed in establishment media in Mexico and more broadly.

La Botz could have sharpened his critique in two important fronts:

1) First the issue of the victory of Bolivia’s indigenous and popular forces registered by the election and re-election of Evo Morales to the Presidency. His MAS government has since been under relentless attack from the imperialist powers and tradition ruling class sectors in Bolivia and the region. Where do the EZLN and its supporters throughout the hemisphere stand on this vital struggle – undoubtedly the high water mark of the rising tide of continental Abya Yala indigenous struggles in our time. Related to this issue is the failure of neo-Zapatism to respond positively to the Bolivarian revolution and the ALBA process. Its response has been a deafening silence.

2) Second and perhaps most importantly, is the failure of Mexico’s neo-Zapatistas to respond to the Oaxaca semi-insurrection in 2006. This “Comuna de Oaxaca” upsurge was arguably far more important in the Mexican class struggle than the Chiapas events of the 90s. Oaxaca State, is neighbour to Chiapas. Some 37 present of its inhabitants speak indigenous languages (Zapotecos, Mixtecos, Mazatecos, Chinantecos, Mixes, Triquis, among others), compared to only 26 present in Chiapas. Four-fifths of the nearly 600 municipalities of Oaxaca State self-govern according to indigenous custom of rotating leaders and popular assemblies. To the extent that the “from below” line of the EZLN had or has any merit, it proved useless in Oaxaca where a genuine, powerful from-below near insurrection occurred in the capital of a state with a huge indigenous population. The Comuna showdown with the national state stretched out over four months and sprouted soviet type mass collaborative structures such as the famous Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (APPO) [see Luis Hernández Navarro, the La Jornada journalist who considers the Comuna to be “one of the most important organizational experiences of the social movement in Mexico”

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2006/11/21/index.php?section=opinion&article=027a1pol ]. The EZLN and its political line of abstention from national politics had only negligible influence on the Oaxaca struggle and on meeting the dire need at the time to mobilize a national and international defence against the fierce repression. Their line blocked those under their influence in Chiapas and other regions of the country from any successful response to the challenge of participating in, much less sustaining, a broad defence – a role they could have played given their prestige and mystique among youth in Mexico and abroad.

The role of myth and confused symbolism about neo-Zapatista ideology is difficult to untangle partly because writers like John Holloway and others have tried to generalize about this movement in questionable, all-purpose prescriptive ways [see Change the World Without Taking Power]. Regis Debray carried off a similar distortion of Guevara’s strategic concepts in his book Révolution dans la révolution? et autres essais (1967) [Revolution in the Revolution?, Grove, 2000]. It offered a so-called hand book for guerrilla warfare, analysing the strategic doctrines then gestating among many Latin American revolutionists trying to escape from the grip of Stalinist and nationalist reformism. It elevated local and regional tactical approaches to a continental or even global strategy or recipe for revolutionary struggle against the ruling class and its state power. The results, as soon became evident, were utterly disastrous for our side.

The Chiapas movement offers many positive lessons – notwithstanding the limitations of its apparent abstentionism and “autonomism.” But the potential for such lessons to be assimilated more broadly and by younger generations is constricted by the false counter position of the “from below” and “from above” orientations – as Oaxaca demonstrated so painfully.

Felipe Stuart

Managua, Nicaragua