by George Scott

November 11, 2013

The piece below was submitted to us by a member of the New York City branch of Solidarity, originally developed as a short presentation on the realities of police brutality and the character of organized opposition in the city.

I want to explore a political question I’ve found more and more important to have an answer to: the role of current police repression in the US. Maybe I should say this differently, since I think we’d all agree capitalists will use various state apparatus to accomplish their goals — I’m looking for a more thorough, more complete, and more nuanced answer that can explain some of our experiences in NYC over the past dozen years. Also, I’m not really talking about the surveillance net being dropped on our heads (thanks for the details, Snowden), and I’m not even focused here on the situations where we’re actively and self-consciously protesting something or another (i.e. NYPD surveillance and infiltration of OWS, other marches, rallies, actions) — I’m talking about people’s direct, in-person experience with the cops on a day-to-day basis. Basically, I’m talking about “stop-and-frisk.”

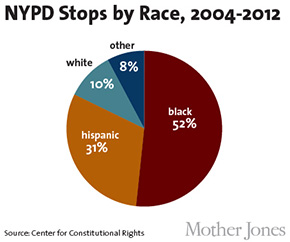

Stop and Frisk by the Numbers

I’m sure many are familiar with much of this, but let me just review some of the statistics about the routine police involvement with New Yorkers:

Demographics of NYC residents (2010 population total was 8.33 million).

- 2.1 million non-Latino Blacks (26%)

- 2.4 million Latinos (29%)

- 2.7 million whites (33%)

- 1.1 million Asians (13%)

- 52.5% of all New Yorkers are categorized by Census as women (in men/women dichotomy, with no breakdown for transgender people).

Data on NYPD Stop-and-Frisks (from NYCLU): the year Bloomberg took office (2002), there were 97,296 stops, with only 18 percent charged with anything. By 2003 this had already risen by about 65% (to 160,851 stops), and the proportion of people charged with any crime or even cited dropped to only 13% of these stops.

Demographics of people stopped by police in 2003

- 77,704 were black (54%)

- 44,581 were Latino (31%)

- 17,623 were white (12%)

- 83,499 were aged 14-24 (55%)

- 87% were identified by police as “male”

The number of stops steadily rose to a peak in 2011, when New Yorkers were stopped by the NYPD 685,724 times (with only 11% charged or cited for any violation).

- 350,743 were black (53%)

- 223,740 were Latino (34%)

- 61,805 were white (9%)

- 341,581 were aged 14-24 (51%)

- 91.5% were identified by police as “male”

To look at these numbers another way, let’s assume that most of these police stops were of different people (many people have reported being stopped multiple times a year, so take these estimates with a grain of salt). Taking all the stops in 2011, let’s say 75% were of different people. Also, let’s assume that the 91.5% identified as “male” is roughly the same for all racial groups. Now, assume that the population was roughly the same in 2011 as during the 2010 Census and that each population is roughly half men/women (again, this is skewed by not accounting for transgender folks). This gives us an estimate that in 2011 alone, the NYPD stopped and frisked:

- 23% of all Black men in New York, and 2% of all Black women

- 13% of all Latino men New York, and 1% of all Latino women

- 3% of all white men New York, and 0.3% of all white women

These numbers would all go up if I were smart enough to adjust them to the age ranges targeted by the NYPD (14-24 y/o), but I think you can get the idea from this. I should also note that though this hasn’t been a focus of any of the class-action court cases cited below, the Anti-Violence Project has reported evidence that transgender women of color face among the highest rates of harassment by the NYPD. Basically, getting stopped and possibly beaten up by the NYPD for no reason is something that is in the experience of most people of color (either they have been stopped or a close family member or friend has been)–especially Black folks–and that VERY few white folks share. Obviously I’d assume that this isn’t news to us, but being a materialist, I felt compelled to dabble in math.

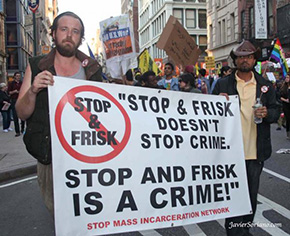

Opposition to Stop and Frisk

Major legal challenges to the NYPD’s Stop-and-Frisk reign of terror:

In a recent article, Malcolm X Grassroots Movement describes the origins of the legal challenges to Stop-and-Frisk, which they were plaintiffs in:

It was in the late 90s after the shooting of Amadou Diallo, that the late Richie Perez, leader of the National Congress of Puerto Rican Rights and the Coalition Against Police Brutality (CAPB), brought the idea of a lawsuit against NYPD’s unjust stops in communities of color to the Center for Constitutional Rights. Djibril Toure of the MXGM was a plaintiff in that 1999 class action lawsuit that was named Daniels v. the City of New York. The Coalition Against Police Brutality, which included the Audre Lorde Project (ALP), CAAAV – Organizing Asian Communities, Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM), the Justice Committee (JC) and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM), organized around the case until it was settled in 2003. They were successfully able to disband the NYPD Street Crimes Unit and get numbers released that showed the NYPD routinely violated the rights of the Black community by subjecting tens of thousands to stops fed by racial profiling

MXGM also participated in a subsequent lawsuit, Floyd et al v City of New York (which included three MXGM members as plaintiffs):

[Using information newly released by the NYPD as a result of the Daniels et al case] that showed an extraordinary increase in stops and frisks, the Center for Constitutional Rights filed a new lawsuit, Floyd v. City of New York. Floyd would challenge the NYPD’s practice of racial profiling and unconstitutional stop and frisks of Black and Latino New Yorkers and would also become a continued fight by MXGM and the other grassroots organizations that organized during the Daniels lawsuit. Many of these organizations became members of the CAPB initiated formation, the Peoples Justice Coalition for Community Control and Police Accountability.

This past summer, Federal Judge Scheindlin decided Floyd in favor of the class action plaintiffs. As the NY Times reported,

The judge found that for much of the last decade, patrol officers had stopped innocent people without any objective reason to suspect them of wrongdoing. But her criticism went beyond the conduct of police officers. “I also conclude that the city’s highest officials have turned a blind eye to the evidence that officers are conducting stops in a racially discriminatory manner,” she wrote, citing statements that Mr. Bloomberg and the police commissioner, Raymond W. Kelly, have made in defending the policy. Judge Scheindlin ordered a number of remedies, including a pilot program in which officers in at least five precincts across the city will wear cameras on their bodies to record street encounters.

Earlier this year, Scheindlin also ruled in Ligon that the NYPD must have probable cause to stop people in private buildings, even when the landlords request extra police presence (they were routinely just harassing the tenants and their families). This case was lead by the ACLU.

Bloomberg has appealed these two latest rulings, but until a week ago, the appeals didn’t seem to be going anywhere, and Scheindlin had refused to delay implementation of her recommendations during the appeals process. But then on Halloween federal appeals court halted the implementation of Scheindlin’s recommendations and went further, removing her from the case–all ostensibly due to her public remarks in response to Bloomberg’s criticisms of her. With de Blasio in the Mayor’s office in January, it’s expected he’d either drop the appeal and basically implement her recommendations, or perhaps use the appeal as leverage to get a settlement without having to deal with a court-appointed monitor.

I should also note that setting aside these major class-action suits, routine Civil Rights lawsuits against the NYPD have cost the City around $520 million in settlements FY 2011-2013 (having grown by astounding 70% from 2006, and roughly 6 times what LA spends defending the LAPD) — Bloomberg refused to change course.

Legislative challenges to Stop-and-Frisk:

Parallel to the legal challenges, advocates and progressive local politicians drafted and campaigned around a package of Municipal legislation called the “Community Safety Act” It’s actually two bills that

- Strengthen the legal prohibition of racial profiling by NYPD and expand the categories that cannot be profiled, including transgender people and homeless. It also Affirm the need for probable cause in order for NYPD to conduct a Stop and Frisk.

- Creates a new independent “Inspector General” to oversee NYPD compliance with the law and judicial rulings (such as the Scheindlin rulings). This was seen as necessary because the NYPD and the Mayor had clearly failed to do this themselves.

The legislation also created a remedy for anyone who successfully shows that the NYPD violated either of these provisions: you cannot win monetary damages, but it can lead to additional specific police practices being automatically prohibited if they are found to contribute to the violation of the law.

The legislation was overwhelmingly passed by the City Council, Bloomberg vetoed it, and the Council then overrode his veto.

Responses to individual cases of police brutality and murder:

- Amadou Diallo (killed 1999): this was a major turning point, and as mentioned above, led to some of the other initiatives. I wasn’t in NYC at the time, and dont’ really know details on that movement in response.

- Sean Bell (killed 2006): a young father murdered along with his friends the night before his wedding. 1199SEIU and Sharpton’s National Action Network (NAN) organized very peaceful, contained march in mid-town, along with series of vigils and press conferences urging ‘restraint’.

- Ramarley Graham (killed 2012): an unarmed teenager shot in his own home. The movement for justice in this case has been very much based in his Bronx neighborhood, and supported by several unaffiliated leftists (Sharpton et al played smaller role this time), and has been much more assertive, less restrained. Rallies have been more consistent and were sustained regularly for about a year afterwards.

- Shantel Davis (killed 2012): Brooklyn saw major rallies, continuing the trend of more assertive, less restrained. Marches were often unpermitted, disobeyed NYPD efforts to disperse them, etc.

- Kimani Gray (killed 2013): Also in Brooklyn, saw enormous marches, even less influence from NAN, Sharpton, NAACP, etc. Marches were termed “riots” by media; they were very angry, aggressive, unrestrained, and organized largely without significant left / organizational infrastructure…largely word spreading among high school students and young adults. Cops had to basically barricade a whole neighborhood.

- Trayvon Martin (killed 2012): Obviously this wasn’t the NYPD, but there were several very large rallies in NYC, all of which clearly identified Zimmerman as a product of the same repressive aparatus as the NYPD. After the verdict this past summer, a huge march in Manhattan was entirely unpermitted, disobeying any NYPD demands, and blocked TimesSquare for hours before most people just got up and went home after nearly 8 hours of marching around and blocking traffic. My estimates were about 10,000 people at it’s height.

Ramarley Graham.

This is far from an exhaustive list of all the people killed by NYPD, or even all the innocent people — those numbers are well into the dozens. This isnt’ even an exhaustive list of the movements in response, but it’s just off the top of my head. 2012 was particularly bloody year, with 21 people killed by NYPD. Several conclusions from this brief summary, though:

- Since I have been following these around 2006, rallies and marches have gotten significantly larger and less restrained (i.e. often without NYPD “march permits”, etc)

- The role of National Action Network has decreased, and with growth of Cop Watch, People’s Justice Coalition and other more solidly left forces, the tone and direction of actions has been increasingly militant

Cop Watch:

MXGM has led a movement in NYC to establish long-term on-going “Cop Watch” initiatives, to monitor and discourage police harassment and abuse. As part of their overall People’s Self-Defense Campaign, MXGM has had a continuously operating Cop Watch program in Central Brooklyn and have trained many other groups to build other groups able to do this work effectively. Around five years ago, MXGM helped found the People’s Justice Coalition, which has focused on further expanding Cop Watch programs across the City and supporting other aspects of the fight against police brutality. The other founding organizations were Audre Lorde Project (ALP), CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities (CAAAV), Justice Committee, Long March Collective, Make The Road New York and Nodutdol for Korean Community Development.

To my knowledge, Cop Watch is the most sustained grass-roots aspect of this entire effort to oppose police harassment and violence. The other initiatives are either lawyer-led (court cases), lobbyist-focused (legislative) or relatively short-lived responses to individual cases of police brutality.

October 22nd Coalition:

I should also mention that there is an older national network of anti-police brutality organizers, called the October 22nd Coalition, which has been organizing national “days of action” (basically marches) every Oct 22nd since 1996. They get props for being so damn consistent for so long! But it’s basically an annual event, without as much on-going work as something like Cop Watch.

Just A Little More Math: Political Economy Under Bloomberg

Poverty:

Over the course of these same 12 years (the Bloomberg years), measures of poverty and income inequality in NYC have dramatically increased, while social services have been cut. The official poverty rate has climbed significantly during the recession, from 18% in 2008 to 21% in 2012 (about the same as in 1980); with another 20% of NYers between 100-200% of the poverty line (in 2012, the poverty line for a 3-person household was $17,916 / yr). These numbers are approx 5% higher than the overall US and NY State statistics. Practically, this leads to 38% of all New Yorkers relying on Medicaid in 2012 and an all-time record-breaking number of people in shelters (48,700 / night in Oct 2012). Of course, these conditions aren’t evenly distributed at all. The official poverty statistics for 2011 (when overall NYC rate was 20.9%) were:

- 23.7% among Blacks

- 30% among Latinos

- 12.4% among whites

- 19.6% among Asians

Income inequality:

Income inequality has risen faster than the national income inequality (which of course is rising very fast). A 2012 report from the NY-based Fiscal Policy Institute, a Union-funded think-tank, concludes that “No state is more polarized than New York, and no large city is more polarized than New York City”, with Blacks and Latinos at the bottom of that scale:

Within New York, a vast gulf exists between Wall Street pay and the average pay for everyone else. In 2011, 190,000 Wall Streeters were paid an average of $348,000 while the average for the other 8.3 million New York workers was $55,000. For about one-fourth of those 8.3 million non-Wall Street workers, hourly wages were not sufficient for a full-time worker to support a 4-person family above the federal poverty threshold.

Massive cuts to benefits and social services:

- Cash assistance: From a height of 1.2 million recipients in 1995, the welfare rolls fell to 460,000 by 2001 and now 365,000 in Dec 2012. This is largely the result of the welfare “reform” under Clinton, but Bloomberg has even further discouraged using this benefit. Community Voices Heard has documented and fought the unnecessary and expensive fingerprinting of applicants, and a impossibly circular bureaucratic requirements that lead to high levels of “Failure to Comply“, and people then have their benefits terminated.

- Foodstamps: Bloomberg tried to force applicants to get fingerprinted to “catch fraud”; this got blocked by the Governor, but yet another example of efforts to reduce benefit utilization.

- Social Service Funding: From 2002-2008 several City agencies saw real increases in funding (compared to inflation): Schools and Child Protective Services. Most services stayed flat, or declined slightly compared to inflation. But since the recession (2008-2013), Bloomberg has been gutting nearly every agency: before accounting for inflation, public hospitals saw 44% cuts (despite utilization increasing), afterschool programs saw 8% cuts, Child Protective Services were hit with nearly 10% cuts. Accounting for inflation makes these even more grim.

- Transfering tax revenue back to Capital: Spending on social services has paled in comparison to the sky-rocketing spending on “economic development” (usually in the form of tax-give-aways to developers): growing from $1 billion / yr in 2001 to nearly $3 billion / yr in 2013 (I think that’s growth at roughly 10x inflation).

- Medicaid: As I mentioned above, increased poverty has increased the rolls of Medicaid recipients. In “liberal” economic models, this would “naturally” increase public spending, provide people with jobs, etc; but in stead, NY State has just finished a 4 year project of slashing Medicaid’s long-term care benefits and putting putting arbitrary caps on total spending (regardless of how many people are enrolled in the program).

Back to the Point: Why Is It All Necessary?

Looking back over the massive effort to harass people of color in NYC over the past dozen years, and Bloomberg’s defiance of the courts and the City Council (which has until very recently been so cooperative with him), I can only conclude that Bloomberg as determined that Stop-and-Frisk is not just another tool of capital among many, but that it is a major and perhaps central tool of social control. So, my question is, “Why is it necessary for capital and it’s political representatives to spend such a huge effort harassing people who are obviously not engaged in anything illegal?”

One answer to that was provided during the course of the Floyd lawsuit: State Senator Eric Adams (a Black former NYPD officer) testified that NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelley told him the NYPD is using stop and frisk “to instill fear into African American and Hispanic youth, so each time they leave their home, they feel as though they can be stopped by the police”. “Instilling fear” is pretty much the textbook definition of terrorism, now isn’t it! That’s an acknowledgement of what so many individuals and families has been experiencing for a long time, but of course doesn’t answer why that terrorism is needed. Here were a few initial thoughts:

- Preventing crime: Nope. If your “modern policing” tactics end up being wrong over 90% of the time, it’s not very effective crime fighting. And while the NYPD justifications shifted to crime prevention, crime continued to decline even as the number of stops has declined since 2011 (in response to opposition outlined above). The stops are not fighting crime, and they are not preventing crime either.

- Protecting wealthy residents: I’m sure this is part of the rationale (especially for stops that occur in downtown Manhattan), but with NYC so segregated, this doesn’t account for the majority of stops. Of the 6 neighborhoods with the highest rates of stop and frisk, maybe one or two are in rapidly gentrifying areas (East Harlem and Williamsburg, Bklyn); the others are not really gentrifying much to my knowledge (i.e. East New York or Brownsville in Bklyn).

- Feeding the Prison Industrial System: This seems obvious, but with so few arrests this doesn’t seem to pan out; besides, the convictions are most likely to be for minor crimes (small amounts of drugs, disorderly conduct, etc), which aren’t going to get you that much time in NYC (some of our worst “get tough” laws have eased up a bit lately).

Though stop-and-frisks don’t produce many arrests, the broader “war on drugs” is very effective at just that. While many have been writing and speaking about this for decades, Michelle Alexander has brought renewed attention to the mass incarceration of people of color with The New Jim Crow. Though incarceration rates in the US are astronomical (roughly 2.3 million), even more extreme are the numbers of people who are on probation and parole (over 5 million in 2008). She outlines the many barriers that these folks face establishing any economic stability: barred from most safety net programs (welfare, public housing, etc) and legally discriminated against in employment and housing (and mostly ineligible to vote). She argues that maintaining this massive population of excluded and exploited people of color outside the prison walls is the most powerful social control aspect of the “New Jim Crow”, effectively economically hobbling entire communities of color, much like the “old” system. She doesn’t develop that argument much further in the book, but recently she’s been moving in that direction, acknowledging intersections of Capital’s imperatives with mass incarceration as a means of social control. So, in addition to all the other inhumane aspects of mass incarceration, it serves to legalizes and enforce an austerity regime on communities of color (centered on a growing population of probationers and parolees) that is far more severe than what is politically possible for the whole population so far.

In his presentations on the necessity of austerity (watch one here), Charlie Post uses a logic around these dynamics that resonates: working class communities of color, especially young Blacks, have been the most consistently rebellious group in past 150 years of American history. Perhaps capital is saying to itself, “These people won’t continue to accept our austerity regime for much longer, so we must pre-emptively terrorize them to discourage any significant rebellion.”

Politically, then, stop-and-frisk is serving a similar function as white vigilante mobs of prior generations that imposed an oppressive but profitable economic system on Blacks and other people of color both North and South. Not directly (like the overseers of exploited laborers, whether enslaved, free or in prison work camps), but by preventing broader rebellion.

If this is simply the latest incarnation of white supremacist vigilante rule using mostly Black and Latino cops, why was it so important to develop this tactic during Bloomberg’s years? Why not earlier? In what ways is it significantly different from earlier versions of racial terrorism? Also, what sort of concrete evidence might we look for or find in NYC — or any given area — of the mechanisms behind these sorts of tactical shifts of white supremacists?

If this line of analysis is going in the right direction, perhaps we–and perhaps especially the white folks among us–need to develop a greater appreciation for how organizing against this is not just about building “organizational capacity”; it’s about confronting terrorism and (to the extent that it’s been effective) the fear that it was intended to create. I know in my workplace organizing, fear of the boss’ power is one of the hardest things to ‘unlearn’; but so often in areas of organizing based on public rallies and marches, I haven’t really appreciated the role that fear might play in our ability to mobilize (as opposed to apathy or hopelessness, for example).

Also, how long and how hard do we think Capital will fight to continue or even expand this specific regime of racial terror? Or is this something that they’ll quickly abandon now that it’s clearly politiclly unpopular in NYC, and just develop alternative strategies for pursuing their interests? Is this the central or even a central tactic of modern Capital nationally, or is it just a NY thing? All these questions seem to have implications for organizing, in that how we position ourselves in these struggles may help or hinder not only the Left’s growth over the coming periods, but the future of these struggles themselves. In NYC, this is an area of organizing that white radicals have been on the sidelines of for far too long, and something I hope we can soon correct.

George Scott is a member of the New York City branch of Solidarity.

Comments

2 responses to “Police Terror in the Big Apple”

From where I’m at (Milwaukee), I would say that ‘stop and frisk’ itself is not a national trend, but is part of the more general intensification of police harassment, violence and murder in racially oppressed neighborhoods. Stop and frisk and similar police strategies are not new at all and will almost certainly be more enduring than any single public program such as ‘stop and frisk.’

You write, “Politically, then, stop-and-frisk is serving a similar function as white vigilante mobs of prior generations that imposed an oppressive but profitable economic system on Blacks and other people of color both North and South. …If this is simply the latest incarnation of white supremacist vigilante rule using mostly Black and Latino cops, why was it so important to develop this tactic during Bloomberg’s years? Why not earlier? In what ways is it significantly different from earlier versions of racial terrorism?”

A look at policing strategies of earlier decades and the nineteenth century suggests to me that ‘stop and frisk’ is not qualitatively different from those previous methods. If we start with the postbellum and Jim Crow South, where the state allowed and sometimes encouraged white lynch mobs to kill and torture blacks, its important to remember that the police and sheriffs themselves were also very active themselves. In this period, state and county prison populations were small compared to later periods, and smaller than one might expect given that the criminalization of black people was a central component of racial capitalism then (through vagrancy laws especially, which basically criminalized any black person who was outside of the authority of a white employer). One historian (I think it was Edward Ayers in his book Vengeance and Justice) writes that in this period of Southern history, the police would frequently choose to harass and beat black people without making an arrest and charging them with a crime. So the impact of police surveillance and brutality was greater than any statistics suggest, was more constant than white mobs, and was broadly speaking similar in purpose to ‘stop and frisk.’

Black neighborhoods in the North in the 1950s and 1960s experienced policing strategies very similar to NYC’s current ‘stop and frisk,’ including one of the same name in Illinois. In Here’s how historian Simon Ezra Balto describes the Chicago police circa 1960:

“…a focal point of [the Chicago Police Dept.’s] approach to law enforcement was to implement an explicit policy of ‘aggressive, preventative patrol” in high-crime, majority-black areas. On the ground, this meant that officers were required to make ‘on view arrests,’ conduct intense field interrogations, and stop ‘suspicious persons’ walking the streets. They began measuring the efficiency of patrolmen in these districts directly by the number of stops and arrests they made. Officers patrolling black neighborhoods recorded large number of arrests for drunkenness and ‘quality of life issues,’ which the department framed as necessary for getting ahead of more serious crime. Summarizing the theory behind his approach and foreshadowing his repeated and eventually successful lobbying in the Illinois legislature for a ‘stop and frisk’ law, Wilson explained to department heads, “as the number of street stops increases, the number of good arrests will also increase.”

In both Milwaukee and Chicago black residents and newspapers said that the intent of police activity was to instill “fear” and “terror” through routine stops, brutality, and murder. (This also provoked considerable and spontaneous community resistance to arrests and ultimately contributed to the riots of the late sixties.)

So I would say that the current policing activities and NYC’s ‘stop and frisk’ are less like vigilante white violence than they are a lot like previous policing strategies, though the two have always worked together. ‘Stop and frisk’ has a much longer history than is often recognized.

Here in Milwaukee, Occupy the Hood-MKE has been calling for a new community review board to replace the current bureaucratic/rubber stamping process for reviewing police offenses.

Jumping off from your point about stop-and-frisk being an official form of this earlier vigilante violence, I’m wondering similarly how stop-and-frisk similarly relate to the question of ground-rent and urban uneven development.

I was just reading a book by Arnold Hirsch called Making the Second Ghetto, which talks about white riots in Chicago 1940-1960, and how those riots and the urban renewal policies were two sides of the same, white supremacist coin. The vigilantes forced/gave an excuse for downtown politicians and business interests to take on urban development and slum clearances. And both were acting based upon their interests in urban development: one in seeing their houses go up or stay the same in value, the other in creating stable capital accumulation for the city as a whole. In some sense–an overly reductive sense–they were reactions to and causes of shifts in ground-rent as the city was growing and expanding, with the unevenness of that growth expressed through white-black relations. The formal and informal violence deployed against black people was used to maintain a status quo of racist social relations while the land prices were shifting beneath their feet.

In New York today, when Ray Kelly says the point is “to instill fear into African American and Hispanic youth, so each time they leave their home, they feel as though they can be stopped by the police,” I think you could also emphasize the fact that he is talking about when they “leave their home.” He’s explicit about drawing territories and creating expectations of where people can and can’t be. The police play a similar role, more directly for landowners, when they are harassing tenants like in the Ligon case. Do these territories of terror map onto places where capital invests and where it disinvests? It sounds like not really, but I bet some more geographic analysis could point to some overlapping patterns.

Also, I think that the policy of (hyper)containment suggested by Kelly’s remarks are kind of on the same spectrum as the containment policy that is enacted through the PIC, so even if the people who are stopped-and-frisked don’t end up in court, it’s part of the same force. Thinking about it in terms of gravity, it’s like police repression contorts the spacetime in some parts of the city so that there’s this force drawing certain people back to “their homes” and keeping them from leaving. In this analogy, prisons are what happens when the city grows and develops massively, and the contortion increases to the point that it creates a black hole, part of the community but transported outside of it.

As a related question, I’ve been thinking recently about how financialization in the broader US economy leads (maybe indirectly) to changes in daily lived experiences. I’ve been thinking that a lot of times the police and the sheriffs act, in a way, as the agents for finance capital, where you could point to cops and say, “That’s finance capital at work.” This is very evident in the role of state repression through foreclosures, but also in terms of trespassing on investments like private buildings or private land. For instance, I was working with a homeless couple here in Chicago who were occupying a vacant foreclosed home, and were later illegally evicted (with guns literally to their heads) by multiple cop cars. It turns out that the home was recently bought by private equity giant Blackstone Group. I feel like this fits into the same relationship, even if it was repression of an intentionally political act (although the cops didn’t know that, and it was also an act of survival for the couple, on one level).