by Dan La Botz

July 31, 2013

The coincidence of the “Justice for Trayvon” protests all over the country and the 50th anniversary of the March of Washington for Jobs and Freedom presents the African American people and all of those concerned with social justice a real opportunity to revive the black freedom and equality movement in the United States. Hundreds of marches and demonstrations have taken place in cities and towns throughout the nation in the last few weeks in a call not only for justice for Travyon Martin but also for an end to racial profiling and to “stand your ground” laws. Those involved in these demonstrations have been mostly African Americans, though Latinos—who face similar issues—were numerous in California and white allies were present in small numbers everywhere. Young African American men and women as well as teenagers showed up in large numbers, easily identifying with Trayvon’s all too common tragic experience.

Rev. Al Sharpton, with a keen sense of opportunity and with a national organization, the National Action Network, called for demonstrations on Saturday, July 20, and tens of thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands—responded in cities across the nation. President Barack Obama’s response to the growing discontent in the African American community — holding a press conference and discussing his own experiences as a black man with white racism — has contributed to a sense that the issue is before us and something must be done. Though strangely, at the same time, Obama considers appointing New York Police Chief Ray Kelly, responsible for the city’s racist stop-and-frisk policy, to be head of Homeland Security.

Protestors flooded Times Square, blocking off traffic, during a march demanding justice for Trayvon Martin. Photo by Anthony J. Hayes.

The Underlying Problem: the Economy

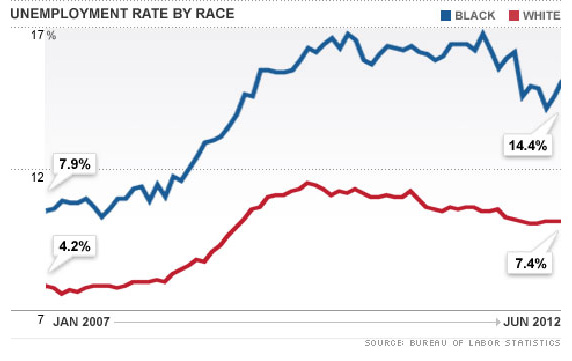

Underlying these demonstrations about Trayvon Martin, racial profiling and what so many perceive as the “criminal injustice system,” is a deeper desire to end racism—economic, social, and political—in America once and for all. Economic inequality stands at the center of the country’s racial problems: the gap between African Americans and other Americans continues to grow. While the United States has its first black president, African Americans have not been so badly off in comparative economic terms for decades. The economic crisis of 2008 may have ended for banks and businesses and for a layer of more prosperous mostly white Americans, but it has not ended for millions of black Americans. While the monthly national unemployment rate remained constant at 7.6 percent, for African Americans it increased to 13.7 percent from 13.5, almost twice that of other Americans.

While joblessness is the immediate problem, the deeper issue is that African Americans have been seeing their assets—bank accounts, pensions, homeownership, automobiles—decline in comparison to those of whites. A study a year ago by the Pew Research Center based on 2009 data found that, “The median wealth of white households is 20 times that of black households and 18 times that of Hispanic households….From 2005 to 2009, inflation-adjusted median wealth fell by 66% among Hispanic households and 53% among black households, compared with just 16% among white households. As a result of these declines [in homeownership and housing values], the typical black household had just $5,677 in wealth (assets minus debts) in 2009; the typical Hispanic household had $6,325 in wealth; and the typical white household had $113,149.”

The Obama administration has not simply neglected the African American population; it has actively pursued policies which are inimical to it. President Obama negotiated NAFTA-like trade deals that lead to a loss of job security and lower wages. He froze federal workers’ wages. He and his Secretary of Education Arnie Duncan have worked to weaken the teachers unions and promoted charter schools, policies that affect the employment and wages of black teachers, and harm African American communities, and students. Obama’s bailout of the auto industry at the beginning of his first term saved the corporations, but several auto plants were closed, thousands of jobs lost, and workers’ wages, conditions and benefits were sacrificed. As corporate taxes have been cut and jobs lost and workers’ wages lowered, the tax base has been eroded, which in turn becomes an excuse for cutting services and laying off public employees, many of whom are black. The bankruptcy of the auto industry capital, Detroit—a bankruptcy that is principally an attempt to eliminate the city’s obligation to pay pensions to about 6,000 retired workers—in a city that is 83 percent African American and 7 percent Latino, symbolizes the state of black America in the era of Obama.

African Americans may be marching now principally because of Trayvon Martin and may also march in August 2013 to commemorate Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s great “I Have a Dream” speech and all that it implied—but they will also be marching because the American economic system is failing them and the American political system and its first black president has not stood up for them. Even as African Americans for completely understandable reasons remain loyal to President Obama, still proud of the accomplishment of election the first black president, they increasingly find intolerable the economic crisis and the continuing racism of American society and begin—if not to criticize the Obama administration—to demand an improvement in the economic and social situation, that is, to demand once again as they did fifty years ago “Jobs and Freedom.” We may be seeing—we hope we are seeing—the beginning of a longer march not simply to Washington and the reflecting pond, but of a march through America from sea to sea.

Black unemployment has consistently been around twice as high as whtie unemployment.

Lessons of the Past

African Americans facing today a deteriorating economic situation and continuing racial discrimination will have to create their own leadership to take them forward. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s—the greatest labor movement in U.S. history since the 1930s—was largely a movement in the South of poor farmers, agricultural laborers, domestic servants, and service and industrial workers (such as sanitation workers and steel workers), as well as of high school students and some college students. Yet, while it was a movement of working people, driven by anger and indignation at their super-exploitation as black workers and at their oppression under the Jim Crow system and white violence, in few places did black working people control the movement.

The movement thrust up from below new organizations—the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)—and pushed forward new leaders, many of them local activists in churches and labor unions, many of them the women of the black communities. Women and men with radical backgrounds, like the modest Ella Baker, played a significant role. The African American poor of the South and the ghetto dwellers of the North pushed forward mostly male leaders of whom the most famous is Martin Luther King, Jr. almost all of them from the black middle class. Yet at the same time this middle class movement was pushed to take up the economic and social demands of its working class base.

While it was a movement against Jim Crow and lynch laws and for civil rights, the civil rights movement was also from the beginning a fight for jobs and higher wages as well and it was economic necessity as much as a demand for social equality that drove it. African Americans made significant strides in the late 1960s and 1970s, winning greater access to corporate jobs and other employment, though mostly in the lower echelons. Yet, the hope for a genuinely more just society for all was not achieved, and the frustration of the movement in the 1960s and 1970s led to the emergence of the more radical Black Power movement, largely destroyed by repression before turning in a nationalist and ultimately pro-black business direction courted by Richard Nixon who embraced the term “black power” and created the Office of Minority Business Enterprise.

A Movement under Middle and Upper Class Leadership

Everywhere, the leadership of the African American civil rights movement was grasped by the historic black business and professional class and by a newly emerging group of corporate black leaders created by the movement’s very success. The black upper- and middle-class professionals tended to have their own understanding of the movement and its goals, which were not necessarily those of the black working class majority. They used the movement to advance their interests in politics, government, and business. Since the end of the 1970s the leadership of the African American community has been in the hands of its traditional and moderate civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the SCLC, of black ministers such as Rev. Jesse Jackson and Rev. Al Sharpton, though in every city African American corporate executives, labor union officials, and Democratic Party politicians have played a somewhat less visible but usually more decisive role.

The “participatory democracy” proposed by Ella Baker and SNCC was obscured by a narrowly construed, financially corrupt, and morally bankrupt electoral democracy dominated by party political machines, political action committees, and advertising and the media. The African American organizations—like the AFL-CIO labor unions and like the National Organization for Women—counted upon the Democratic Party as their shield if not their sword. It failed them. The Democrats, dependent on funding from the world of high finance and big business had no desire to and could not go after the banks foreclosing on black people or the corporations busting unions.

The 1963 March on Washington.

A New Opportunity

The mass movement for Justice for Trayvon, the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington, and the economic crisis facing the black community represent an opportunity for the reconstruction of a civil rights movement. Once again it will principally be youth and working class African Americans and white allies—and today their Latino allies as well—who will propel the movement forward. What is missing in the equation at present is an independent black workers’ movement that could give the movement both the truly representative character and the power that it would need to change our economy, society and government. While black workers make up a disproportionate share of service and industrial workers and of union members, they have yet to wrest the unions from leaders committed to partnership with the employers and dependence on the Democratic Party. To change that situation it black workers will have to join with their white, Latino and other immigrant coworkers to build a broad rank-and-file movement that can turn the unions from compromise followed by retreat to conflict followed by advance. We are not yet there.

When we do get there, when we have that combination of African American working class power, a broad social alliance with Latino and white workers, and an independent political movement, the goal will be to wrest power form the banks and corporations and to create a democratic and egalitarian society. A working class movement in America, of which African Americans will form a leading component, will put back on the American agenda the demand for jobs for all, for a living wage, for free public education from K to Ph.D., and for an end to corporate health care and instead free universal health care. Implicit in every modern struggle for justice is the struggle against the corporations and against capitalism and for the alternative whose historic name is socialism. It is not surprising that A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, James Farmer and other African American socialists were among the organizers of the great March on Washington in 1963.

We are not there yet, but we may be on the cusp of a new African American movement with the possibility of reviving the labor movement and through independent political action challenging the vicious two-party system which holds us all prisoners. We will be marching for Trayvon in our hometowns, we will be marching in Washington in August, and we will be either activists or allies of the new African American movement on which the fate of democracy and social justice in America will once again rely to carry us forward.

Dan La Botz is a member of Solidarity in Cincinnati. This article was originally published in New Politics.