Posted September 9, 2011

By Carl Finamore

“People Wasn’t Made to Burn: A True Story of Race, Murder, and Justice in Chicago”

“People Wasn’t Made to Burn: A True Story of Race, Murder, and Justice in Chicago”

Joe Allen, Haymarket Press, published July 2011

“People Wasn’t Made to Burn,” by journalist Joe Allen, reads like a lively, creative work of fiction with its abundance of larger-than-life characters and a seemingly over-dramatized back story of shocking events awaiting one Black family escaping southern rural poverty and landing amidst northern urban racism. The story includes corruption, greed, a heavy dose of Chicago political intrigue and finally, arson, death and murder. It even has a surprise ending.

It has all the ingredients of a late-night bedside read, but it is all too real.

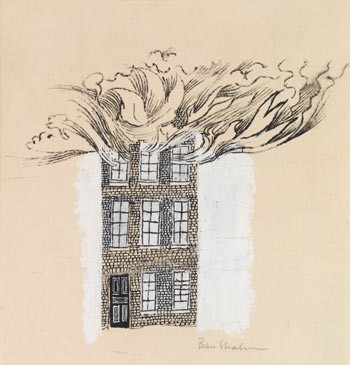

It is, in fact, the actual and very personal story of one Mississippi Black sharecropping family that faced multiple tragedies after moving north to Chicago in 1947. Within a year of their arrival, their dreams of a better life were extinguished. Four of their young children died in a fiery blaze in their overcrowded, dilapidated tenement.

Locked exit doors, inaccessible fire escapes and other intolerable conditions prevented the children from escaping. Unsafe living conditions had previously been reported by the James Hickman family and ignored by apathetic police, inept fire authorities, and corrupt city housing officials.

After experiencing the horrific loss of four of their infant children, the inconsolably distraught father shot and killed the landlord thought to have set the fire.

The landlord had consistently escaped justice for his alleged unconscionable deeds through the bungling and apathy of Chicago officials when, finally, an emotionally overwhelmed Hickman took justice into his own hands. He was promptly jailed and faced murder charges.

Though the events described are quite extraordinary, the experience of the Hickman family serves as the common narrative for millions of other southern Blacks living in post-WWII northern squalor.

Who is Really Guilty of Murder

Woven throughout by the author is another important and instructive historical reference. It takes the reader through the formation of the James Hickman Defense Committee and an inside look into its strategy and leadership by an assorted group of trade unionists, civil rights activists, attorneys, socialists and, of all things, prominent stage and screen actress Tallulah Bankhead. All came to defend Hickman, united in one powerful defense committee intent on exposing the criminal living conditions prevailing in the Black slums.

Fortunately, several committee members were already veterans of struggle. Frank Fried, my good friend, lone surviving member of the defense group and cited by Allen as the book’s inspiration, was among them. He now lives the retired life in Alameda, California but was then fresh out of the Navy and unemployed. He was available to do the “leg work” of the committee.

“I had lots of energy, I was only twenty years old and besides, I already considered myself a revolutionary,” he told me. “Our small socialist group was working with west-side tenants around the brutal housing conditions before the Hickman case so we were involved from the start of his defense because we were part of the struggle from the start.”

All that political and practical experience would come in handy since Hickman freely admitted to shooting the landlord. Plus, there were hostile witnesses as well. Nonetheless, the Hickman committee successfully turned the tables on city authorities for allowing such horrid social conditions to exist.

“The big thing,” Fried explained to me, “is that the defense committee created an atmosphere in Chicago, and to a lesser degree around the country, that made it impossible for them to convict him of murder. Significant sections of the labor movement, for example, backed Hickman.

“He was a worker and he was a victim of class injustice because he was Black and poor and forced to live in segregated impoverished neighborhoods. We successfully injected that social understanding and solidarity into the labor movement.”

Fried was among the small number of revolutionaries organized in the Socialist Workers Party that originated the Hickman Defense Committee. The extremely qualified and experienced lead attorney was also a member.

Even though no longer a member for several decades, Fried still says with great pride that “it was among the party’s finest moments, I thought.”

The Defense Does Not Rest

The investigation, discovery, and presentation of broader extenuating social circumstances into a criminal case is commonly called a political defense and is shunned by most defense attorneys and, certainly, almost always ruled out of order by judges.

It is best, we are counseled, to stay focused exclusively on the facts of the case. Who did what, where, and when.

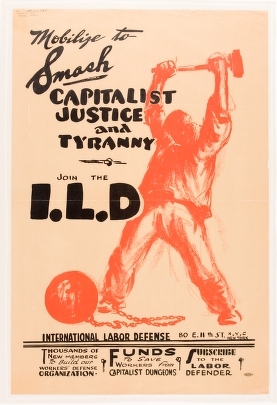

But the Hickman Defense Committee’s radical originators traced their heritage to the historic International Labor Defense (ILD) committee of the 1920s that built extremely broad support for Sacco and Vanzetti and other lesser-known framed-up poor workers.

But the Hickman Defense Committee’s radical originators traced their heritage to the historic International Labor Defense (ILD) committee of the 1920s that built extremely broad support for Sacco and Vanzetti and other lesser-known framed-up poor workers.

The Hickman Defense Committee initial core of leaders took their lead, for example, from ILD founder, James P. Cannon who once described “the real story of the ILD” as “the scrupulous handling and public accounting of its funds and the broad, out-going, non-partisan spirit in which all its activities were conducted.”

Modeled on this united-front approach, all defenders of Hickman’s defense were welcome, regardless of political views on other subjects and regardless of the views of Hickman himself who, apparently, held deeply-avowed, almost mystical or visionary, religious conceptions.

None of this mattered. What mattered was that Hickman was a victim of racist segregation and mistreatment in Chicago every bit as wretched as what he experienced at the hands of the southern plutocracy.

Northern Segregation Was Entrenched

For example, it was common to cram dozens of families into the same three and four room tenements, to gouge them for abnormally high rent and utilities and then to eventually pressure them to move out so that higher rents could be charged to the next group of unaware, naive and desperate southern refugees; all of whom were confined in their search to the overcrowded, segregated Chicago Black neighborhoods.

Sometimes, landlords would actually burn out discontented tenants when they gradually began to protest their conditions. In fact, in court testimony, it was noted that Hickman’s landlord threatened several times “to burn them out” along with other complaining tenants.

These extreme and inhumane conditions often lead to extreme reactions. And herein describes the essence of Hickman’s political defense.

Years later in 1965, Martin Luther King would describe the “de-facto segregation” in Chicago as among the worst in America. As a native Chicagoan, I vividly recall accounts of King being assaulted as he marched through neighborhoods, leading him to remark after one famously televised incident of rock throwing on August 5, 1966, that ‘‘I have seen many demonstrations in the south but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today.’’

The deeply entrenched racism in Chicago and throughout the north make even more remarkable the success of the Hickman Defense Committee two decades prior to King‘s monumental crusade.

City prosecutors were ultimately pressured to admit mitigating circumstances and they dropped murder charges, allowing Hickman to plead guilty to manslaughter and to be released on probation.

He spent the rest of his life with his wife and surviving two children without ever again coming to the attention of the law. This truly amazing outcome is described poignantly by Allen.

Thus, we learn not only the horrendous conditions faced by this one family and by millions of other Blacks who ventured north to escape poverty, but we also learn of the intrepid efforts of Chicago’s “left,” on the eve of the McCarthy “witch-hunt” period, to politically defend marginal victims of social injustice.

Years later, I came to know several of these Chicago defense committee leaders during my anti-Vietnam war protest days. Their experience was once again put into play as we sought to involve the broadest possible united opposition to the war regardless of opposing political views we may have had on other issues.

I very much appreciated Allen’s biographical research of these radical activists and shall never forget the contributions several of them personally passed along to me and to other young activists in the decades after Hickman.

The current generation, I think, can also learn much by reading their story.

Carl Finamore was born in Chicago and raised in the all-white segregated northwest side. He is now a Machinist union delegate to the San Francisco Labor Council, AFL-CIO. He can be reached at local1781 (at) yahoo (dot) com

Comments

One response to “Chicago Burning: Review of “People Wasn’t Made to Burn””

Shalom,My Name is Willis Sims I live in Israel,I’m Jewish and I’m James Hickman’s Grandson, I am suffering greatly due to the terrible tragedy of losing my uncles and aunties in that fire on that terrible day, being Jewish we have suffered enough,yet this is another Holocaust in my life and the life of my family, I wake up crying sometimes from nightmares and sometimes from just thinking about the burning of those babies and the pain and suffering my Grandparents, my mother and her siblings had to endure.My Grandfather did what he had to do,yes this is another Holocaust in our lives but when will it end? My Grandfather was a Godly man and he raised me to be the same, so I’m here in Israel standing on the front line representing our Jewish heritage.Willis Sims