by Katie O’Reilly

August 6, 2015

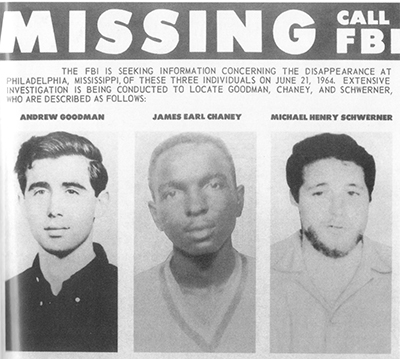

In June of 1964, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, along with more than a thousand fellow young volunteers, ventured to the deepest South—Neshoba County, Mississippi. Their goal was to mobilize voter education and registration among Mississippi’s African American population, long besieged by bombings, murders, vandalism, and intimidation at the polls. Chaney, a twenty-one-year-old Black Mississippian, and Goodman and Schwerner, twenty- and twenty-four-year-old New York Jews, had set out to establish a  Freedom School—one of about thirty such pop-up facilities designed to educate disenfranchised and often illiterate Black Mississippians about African American history and their people’s vast political displacement. Instead, these young volunteers were kidnapped and shot at point-blank range, their mutilated bodies to be found buried beneath an earthen dam forty-four days later. Most members of the mob responsible for killing them went un-prosecuted.

Freedom School—one of about thirty such pop-up facilities designed to educate disenfranchised and often illiterate Black Mississippians about African American history and their people’s vast political displacement. Instead, these young volunteers were kidnapped and shot at point-blank range, their mutilated bodies to be found buried beneath an earthen dam forty-four days later. Most members of the mob responsible for killing them went un-prosecuted.

In a White House ceremony on November 24, 2014, President Barack Obama awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to the families of these three volunteers slain by Mississippi Klansmen on June 21, 1964—the first day of “Freedom Summer.”

During Spring of 2014, US Representative Bennie Thompson, a Black Mississippian, had urged the president to honor these three civil rights workers, to “remind the American public of the great cost incurred by ordinary American civilians to protect our freedoms.”

Along with Thompson, US Senator Kristen Gillibrand, of Goodman’s and Schwerner’s native New York, co-sponsored legislation to award the trio Congressional Gold Medals, stating, “Voting is one of the most sacred rights we have as Americans, and it is important for us to honor those who have fought to ensure every citizen has access to that basic freedom.”

When asked for comment on the medals, Rita Bender, Schwerner’s widow—and the woman who in 1964 gained notoriety for telling President Lyndon B. Johnson “This is not a social call,” when she met with him to demand federal investigation into the Mississippi murders—just noted that the “very best honor” Congress could bestow upon her late husband and others killed or injured in the struggle for voting rights would be “the reinstatement of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and its aggressive enforcement.”

When I moved from Los Angeles to North Carolina during the summer of 2013, the Tar Heel State’s legislators were beginning to make national headlines for their restrictive new voting laws, for their sudden refusal to expand Medicaid to their 500,000 working poor, for cutting unemployment benefits, and for the type of strategic redistricting that, when done in a former Confederate state, arouses suspicions of racial gerrymandering.

In June 2013, substantial sections of the Voters’ Rights Act of 1965—a promise to African Americans that they could finally register and vote without fear of intimidation, retaliation, violence, and death—had expired. They were in fact those protective provisions put in place after hundreds in the South were killed in the name of voter suppression. So, around the time I was registering to vote in my new state, no-longer-limited lawmakers were busy mandating photo IDs and shortening early, absentee, and provisional voting periods—measures that to many, seemed conspicuously aimed at keeping Black, rural, and college-aged citizens away from the polls.

What I’m going to say next may sound naive, but as a Caucasian member of Generation Y and a recent transplant from California—where you can vote in almost any precinct you want, without ever being asked to show any form of identification—I’d never considered that in this day and age, people could still be facing obstacles just to get to the polls. Shortened voting periods, however, stand to complicate poll-going, particularly if you happen to work a ten-hour-a-day, blue-collar job. Also, we all know driver’s licenses don’t come free (remember poll taxes?), and many rural North Carolinians were never actually granted time-specific birth certificates, nor social security records.

“Around here, the Bible was many folks’ birth certificates,” says Bob Zellner, a North Carolinian, decorated veteran of the Civil Rights Movement, and the author of the memoir The Wrong Side of Murder Creek: A White Southerner in the Freedom Movement (NewSouth Books, 2008). “They killed MLK, they killed Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X and Kennedy, and thousands more,” Zellner continues in a syrupy, native Alabamian drawl. “And today, through illegal redistricting and massive voter suppression, the reactionary regime is doing its damndest to take over the most progressive state in the South.”

When I arrived to work as a public radio reporter in Wilmington, a steepled university town on North Carolina’s Southeast coast, the state’s leaders were catching flak for passing bills to defund women’s health centers and to reduce per-pupil public education funding at all levels—their reasoning being that Democrats’ years of corruption and overspending had bankrupted the state. It is debatable whether North Carolina—a competitive state perceived as a burgeoning economic powerhouse with some of the nation’s finest universities—simply became frustrated with its struggling economy and therefore took a chance on GOP rule, or whether it had more to do with Republicans’ aggressive 2011 redistricting of the legislature (passed when then-governor Bev Perdue, a Democrat, held no veto power): red-ruled North Carolina counts 2.7 million registered Democrats to two million Republicans.

Granted, down here the definitions of “Republican” and “Democrat” have undergone several Dixiefied revisions amounting to a 180-degree swap since Reconstruction. But it is notable that in 2012, the current iteration of conservative GOP-ers assumed control of North Carolina’s House, Senate and Executive branches—their first such triumvirate in one hundred forty years.

By the time North Carolina’s 2012 election ballots were tallied, many Southern progressives had seen the writing on the wall—their enlightened swing state, long known for its singular political shade of deep, Dixie purple, was fast becoming an incubator for Tea Party-style policies.

Nowadays, however, some say that the state formerly known as the South’s beacon of progress is undergoing its third Reconstruction. Espousing this view perhaps most vehemently is the Reverend William Barber II, the broad, mustachioed and ultra-charismatic leader of the South’s largest state National Association For the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) chapter, and the recent recipient of the International Martin Luther King Jr. Award for peace.

According to Reverend Barber’s math, the state’s second Reconstruction took place during the 1960’s-era Civil Rights Movement, when many citizens gave their lives to end segregation, Jim Crow laws, poll taxes, literacy tests, church bombings, and the countless other forms of oppression that arose in wake of the first Reconstruction—that eponymous period following the South’s defeat in the Civil War, and the emancipation that followed.

In the course of the Civil Rights Movement’s large-scale attempt to redress the South’s enduring and oppressive racial caste system, unprecedented efforts were implemented—among them sit-ins, boycotts, marches, and herculean feats of legal action to end segregation, as well as housing and hiring discrimination, and efforts to secure voting rights for all citizens. The movement’s legacy lives on in the form of the Civil Rights Act of 1665, The Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

But today, Barber and several fellow civic leaders fear those advancements are being reversed—a mentality made evident in the rallying cry the NC NAACP adopted in 2013: “Forward together—not one step back!”

“It’s because so much of that progress we made in the sixties has been basically overthrown,” explains Zellner, an activist who, at Reverend Barber’s request, recently moved from New York, where he taught history at Southampton College of Long Island University, down to the small, mixed-race, working-class city of Wilson, to help the NC NAACP spearhead Reconstruction 3.0.

A Moral Monday protest.

By the time I’d registered as a driver's license-holding North Carolinian, the NC NAACP, along with likeminded civil rights groups, had made a Monday habit of storming their state capitol to demonstrate in plain view of their lawmakers. Beginning in April 2013 and enduring week after week, during rain, shine, and 100-plus-percent humidity, thousands of people, led by the Moses-esque Barber, were descending upon Raleigh to protest the onslaught of their state’s controversial new legislation—and in the process, hundreds of them were getting “peacefully arrested.” This cycle is known as “Moral Mondays,” and after arriving in North Carolina, I soon learned that among my neighbors, it had become a household term—not unlike the way “sit-ins” and “Freedom Rides” edged their way into everyday lexicon during the South’s “second Reconstruction.”

And when the General Assembly adjourned in 2013, the “Moral” activity did not end. In fact, it blossomed into a full-scale, statewide and remarkably unpartisan-in-name “Moral Movement”—marked by hundreds of hyperlocal rallies, as well as the coalition of groups both faith-based and not; African American and white; working-class and moneyed; queer and straight; along with Latinos, educators, laborers, and military veterans.

The seeds of this movement had been planted back in 2006, when Reverend Barber, still new to his leadership position, launched the Historic Thousands on Jones Street People’s Assembly Coalition. For the February 2007 inception of “HKonJ,” as it’s better known, thousands of citizens gathered on Raleigh’s Jones Street, which flanks the capitol, in support of Barber’s just-penned, fourteen-point “People’s Agenda,” a landmark manifesto calling for well-funded and diverse public schools, livable wages and health care for all North Carolinians, and re-dress for ugly portions of the state’s history, including racial coups and the forced sterilization of Black women.

Thereafter, HKonJ became a significant annual march, its fourteen points burned into the memories of many of its yearly demonstrators who continued to fight for the General Assembly to consider their progressive reforms. So, by the time Barber needed bodies to give up their Mondays to protest regressive legislation, he knew where to find them. It’s worth mentioning that in both 2014 and 2015, the HKonJ rally attracted 80,000 North Carolinians—making it these the largest civil rights marches the South has seen since Selma’s in 1965.

On March 18, 2014, the New York Times reported that North Carolina’s Moral Monday movement had spread to Georgia, where thirty-nine that day had been arrested for their similarly choreographed waves of civil disobedience. The Georgian dissenters were protesting their state’s refusal to expand Medicaid benefits as part of the Affordable Care Act. That same day, several members of South Carolina’s brand-new “Truthful Tuesday” coalition were arrested outside their statehouse in Columbia. The same article noted that the “moral” model is indeed proliferating, with similar groups budding within Florida and Alabama, and even north of the Mason-Dixon, in Wisconsin and New York.

North Carolina activists, however, remain the Moral forerunners, having taken the movement the furthest. Early on, Reverend Barber spoke about how state’s most imperative threat, massive voter disenfranchisement, stood to undermine the democratic principles on which all “moral” activity was based. Barber is often quick to note that it’s not about who North Carolinians are voting for; so much as it is that they’re exercising that democratic right. So prior to his state’s November election—a nationally prominent race into which more out-of-state money was funneled than any other mid-term in American history—the NC NAACP took its grassroots movement a huge step further.

It amassed a crew of “Moral Freedom Summer fighters” to run a nonpartisan voter empowerment campaign—the most comprehensive effort of its kind to take place this century. The fifteen-week initiative, “Moral Freedom Summer,” involved the intensive training of thirty-nine organizers under the age of thirty-five, all of whom were then dispatched across the state to provide citizen education and voter registration within forty-one of North Carolina’s most rural and/or African American-populated counties.

In designing this initiative, the NC NAACP took a card from the most radical voter empowerment effort in US history: the blood-tainted “Freedom Summer” campaign. Yes, Moral Freedom Summer was modeled closely after 1964’s sweeping drive to register as many Black voters as possible in Mississippi—the state most notorious at the time for its white supremacists, and for its violent voter suppression tactics. While the Freedom Summer campaign was marked by controversy, murder, and unmet voter registration goals, its symbolic legacy was massive: It is widely considered to have helped bring an end to widespread lynching and police tyranny in the South, and it brought the region’s deep-seated racial tensions into the national spotlight.

2014, the year Obama bestowed the United States’ highest civilian honor upon Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman, also marked the fiftieth anniversary of Freedom Summer—a historical phenomenon that, whenever history scholars are asked to name decisive turning points in the American Civil Rights Movement, ranks right alongside the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington.

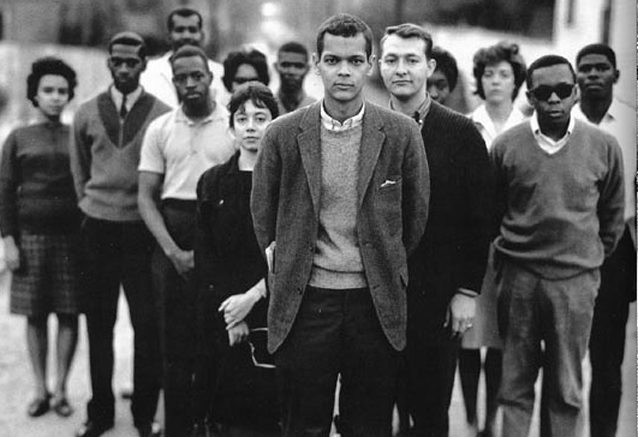

Over the course of two weeks of orientation during June of 1964, Freedom Summer activists prepared to battle the Deep South’s most virulent segregationists. Their training, led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), along with other major civil rights organizers, took place on the leafy campus of Ohio’s Western College for Women, now part of Miami University of Ohio.

The bulk of these volunteers’ education centered around the tenets of nonviolent resistance—aka “not fighting back”—the brand of activism favored by Martin Luther King Jr. As Zellner, SNCC’s first-ever white field secretary and one of Freedom Summer’s project directors, explains, “What this involves is asking yourself, what do you do when someone spits in your face, calls you a name, threatens you?”

SNCC Freedom Summer volunteers, 1964.

By 1964, students and other Northern activists and idealists had begun the process of integrating public accommodations, registering adults to vote, and organizing various networks of local leadership in the South. The formal recruitment of Freedom Summer volunteers began in March of 1964, following the success of 1963’s Freedom Ballot—a mock fall election that civil rights leaders hosted to help determine how many Black Mississippians would come out to vote if they could—as well as some subsequent registration efforts in Klan-dominated Greenwood, Mississippi.

Freedom Summer volunteers—primarily students and recent graduates farmed from top universities in the North—not only had to physically learn how to take a beating; they were told they had to be able to endure some grim certainties that summer. “We all consciously prepared for beatings, for arrests, and for the very real possibility that someone would be killed,” Zellner says.

North Carolina’s new, fifty-six-page Voter Identification Verification Act (VIVA), a bill that spells out the drastic tightening of voting laws, was passed into action during the summer of 2013. However, the NC NAACP, along with groups including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the US Justice Department, have since filed several lawsuits against the state, citing the bill’s potential for racial discrimination.

But under the best of circumstances—if they win on all charged counts—the earliest these groups can hope to see any change is 2016. So in the meantime, people like twenty-year-old Rebekah Barber and her fellow Moral Freedom Fighters have taken it upon themselves to counteract the law’s potential repercussions. The third of Reverend Barber’s five children, Rebekah seems to have inherited her father’s curly hair, as well as his gentle yet fiercely articulate manner of speaking.

“We couldn’t undo that damage in time for the 2014 election,” she says, “so I got on board for Moral Freedom Summer understanding that what we could do was work to prevent voter intimidation, and to teach citizens about what was happening to their rights.”

It’s worth noting that voter intimidation is currently a very real phenomenon in North Carolina. Prior to this past midterm election, for instance, incumbent state Senate pro tem Phil Berger, a conservative Republican, ran an ad insinuating that citizens would be required to present photo identification to vote in 2014, when in fact, according to the law, that stipulation cannot legally be enforced until 2016’s election.

So when school let out last spring at North Carolina Central University, a historically Black college in Durham where Barber is an English major with honors, she headed to Greensboro—site of the 1960 Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-ins that arguably propelled the Civil Rights Movement onto the nation’s public stage—and set up camp at Bennett College. The bucolic campus of this small, historically Black women’s college served as training grounds for an intensive weeklong Freedom Fighter prep session.

From dawn to dusk, the thirty-nine Moral Freedom Fighters—mainly students and recent graduates recruited from colleges and community groups across the state—learned all about social movement theory, with an emphasis on civil rights history. Theirs, however, was no typical classroom set-up—civil rights veterans served as the young organizers’ instructors’, and Reverend Barber himself presided over their education. Homework assignments involved perusing the very same documents that were created to train Freedom Summer’s volunteers back in 1964—think voter registration manuals taken from the SNCC archives.

I’m thirty, and it’s been my experience that today’s is an age wherein young people tend to channel their civic outrage into Facebook posts, to sign online petitions with a quick click, and to perhaps treat the occasional blog post like an op-ed. The focus in Greensboro, however, was organizing “on the ground.” And that ground, says Zellner—who endured his eighteenth arrest at 2013’s pilot Moral Mondays protest, and who last summer helped to train and house Moral Freedom Fighters—is an offline entity. “The ground is where the people are, so the education was about talking, and about hands-on instruction.”

Along with fellow civil rights survivors, Zellner’s role in the training process was to simply talk about what happened in 1964 and relate it to 2014. He notes, “Some of this organizing was completely different”—for instance, that summer’s young people could focus solely on their education messages, and worry far less about ways to handle lynch mobs—“but there were a lot of common themes.”

To uncover those themes, Rebekah Barber and her cohort were schooled in NAACP history, HKonJ’s fourteen points, the philosophies underlying the Moral Movement, and their own state’s history. “Our school systems certainly aren’t teaching us all this information,” Barber reflects, “so it was absolutely eye-opening for us.”

She says that above all, Moral Freedom Summer training provided “lots of insights into the fact that what we were doing was so much bigger than ourselves.” She explains, “We could see that this”—this taking of the philosophies to the ground, into the communities—“had been in the making for years, and that it was up to us to actually make it happen.”

Rebekah left training and headed to her “station,” Wayne County’s mixed-race city of Goldsboro, with a few clear goals in mind. “It was important to me to register at least five citizens each day, including weekends,” she says. “And every Sunday, I’d visit multiple Protestant churches in an effort to strike up these important conversations about what’s going on in North Carolina.”

1964’s Freedom Summer was christened Freedom Summer because what it ostensibly called for was a symbolic end to the institutional slavery still plaguing the South. “If it did nothing else,” Zellner says, “it ended lynch terror for Black males in the South—it took away the weapon that let Southerners do what they did to Emmet Till, to Mickey Schwerner, and to so many more.”

In 2014, Moral Freedom Summer’s objective was the nonpartisan coalition of groups that stood to become disenfranchised by North Carolina’s restrictive voting laws and redistricting patterns. Overtly, it wasn’t about progressive reform at all. And that’s implicit even within Moral Freedom Summer’s nomenclature.

Aside from paying obvious tribute to its inspiration—the 1964 Freedom Summer campaign after which it was modeled—it is no accident that Moral Freedom Summer employs the kind of language commonly found within Tea Party literature. It conjures “moral” choices, and seems like a “freedom thing,” a matter of exercising one’s constitutional rights. And according to Zellner, this evidences a very deliberate choice.

“The NC NAACP and its progressive partners are using the flag and the constitution in part because we want to enforce that these symbols belong to the people—not to political extremists, not to the Tea Party,” he says. “After all, this is not a Black-and-white thing—the extremist legislation in North Carolina isn’t doing anyone any favors except for maybe the top one percent. And the only reason so many North Carolina citizens are still voting against their interests is because they’ve been strategically handed racism and homophobia and antiwoman rhetoric—packaged nicely as ‘family values’— to make them feel like they have any power at all.” Zellner adds that, in fact, Barber coined “Moral Monday” very intentionally, in hopes that it might make people think of the “Moral Majority.”

Zellner says that up until now, it’s been financially supported interest groups that have managed to commandeer working-class, populist lingo, and that they’ve in fact used such rhetoric to hurt working-class Americans. “It’s a flimflam that’s been going on for four centuries in the United States,” he says. “Consider slavery—it wasn’t the planters out there fighting for the Confederacy; most people in the South didn’t even have slaves, but there they were, giving their lives for the very cause of slavery.”

While Freedom Summer of 1964 garnered attention, support, and even guest visits from the likes of actors Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, and Marlon Brando, Zellner believes such star power wouldn’t be prudent for the Moral Movement. “Beyoncé and Jay-Z have expressed some interest in speaking out on behalf of it,” he says, noting that the Moral Movement enjoys behind-the-scenes support from high-profile names, “but it’s probably best that we keep it that way, so as not to alienate the people on the ground, here in North Carolina.”

Zellner, whose family counts a long line of robe-wearing Klan members, has the benefit of keen insight into the working-class Southern white man, the very specimen fiscal conservatives have long counted upon to maintain their power balance. His father, a Methodist preacher from Alabama, ultimately traded in his white hood for the teachings of MLK and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference after a Klan trip to Nazi Germany led the preacher to two epiphanies: that converting European Jews to Christianity was no reasonable nor viable way to save them from Third Reich tyranny, and that, when you’re stationed in a foreign country, marooned and lonely, and members of a touring Black gospel choir from the United States take you under their wing and become your closest friends, you no longer feel so great about persecuting African Americans once back on American soil.

“He used to talk about how he’d ‘forget’ they were Black, that he and they were supposed to be ‘fundamentally different,’” Zellner says, “which of course led him to believe that no, they weren’t so fundamentally different.”

His Alabama grandfather and uncles, however, remained entrenched in the KKK throughout their lives—so Zellner knows a thing or two about how to make inroads with right-wing conservatives and white supremacists. And these are groups that the Moral Movement is actively targeting for inclusion.

“I often go into local Tea Party or Klan meetings here in Wilson, and people might be skeptical, knowing I was part of the Civil Rights Movement, but then I mention, ‘Daddy and Mom both went to Bob Jones College,’” Zellner says. A South Carolina university long known for its outsized conservative political influence, he describes it as the ‘original Klan college,’ explaining, “They still practiced segregation until eight or ten years ago.” What’s more, founder Dr. Bob Jones was Zellner’s godfather; “He married my parents.”

When he’s at these meetings, Zellner asks members about their concerns, gets to know them. “Our work in the Moral Movement involves going all in with a community’s people—attending their funerals and church potlucks, and asking, ‘How can we help?’ It means taking what you hear and helping that community to organize. So when you find out that factory workers are nervous they’ll lose their jobs, that working-class parents are worried about getting their kids into pre-K, it’s about letting them know that you can help them take matters into their own hands.”

Zellner isn’t the only North Carolina activist who knows how to meet its citizens on their own ground. Reverend Barber, in fact, has been known to go into lily-white counties and tell people, “I’m a conservative.” As a faith leader, his values in many ways do align with those held by typical Southern white Republicans. Having gained such citizens’ trust, he’ll then explain to them how the Moral Movement stands to improve their lot.

“That’s how he’s got hundreds of whites suddenly joining their local NAACP chapters,” Zellner says. He says it’s also why Moral Mondays protesters are about 60 percent white, the rest a mixture of mainly African Americans and Latinos.

In this movement, Zellner says, it’s crucial to ally oneself with the common man—he who wants to do right by his family, by his country, by his church, what have you. “It’s not about showing anyone how radical you are; it’s about finding that common ground.”

Zellner describes the Moral Movement’s all-inclusive nature as a working model of “fusion politics.” A term coined to describe the South’s Black-white coalition during the first Reconstruction, fusion politics refers to movements that bring together a range of different groups. In the Moral Movement’s case, this includes the faith community, Blacks, white, Latinos, education and labor activists, the poor and working-class, and the LGBTQ community—“really all of disenfranchised North Carolina,” Zellner says. “For fusion,” he continues, “isn’t about partisan politics, but rather it’s about acting together, according to a shared notion of what’s right and just.”

Moral Freedom Summer participants, 2014.

Moral Freedom Summer 2014 naturally called for a lot of planning and fundraising. The NC NAACP planted those first seeds in 2012, at the Highlander Research and Education Center, a social justice training school in New Market, Tennessee, that specializes in educating those fighting for Appalachian, labor, and civil rights.

Back before local backlash against Highlander’s pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement led to its temporary closure, it was known as the Highlander Folk School, and its facilities were based in mountainous Monteagle, Tennessee. There, Highlander founders trained Rosa Parks for her historic role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Highlander also served as ground zero for much of SNCC’s early planning activity in the sixties.

Zellner first met Barber at SNCC’s fiftieth anniversary conference in 2010, where the reverend delivered the keynote speech. The two stayed in touch, and two years later, Zellner found himself back at Highlander—which he actually called home during much of the early sixties—helping Barber to plan Moral Freedom Summer. Also present were many of Barber’s friends and fellow faith leaders, as well as labor activists, all manner of social justice advocates, and William Barber III, Rebekah’s twenty-three-year-old brother. The field secretary for the North Carolina NAACP’s youth and college division, Barber looks and sounds like a younger and somewhat more pensive version of his gregarious father.

In 2012, the NAACP held several planning meetings prior to the half-centennial heyday of civil rights remembrance—the upcoming series of watershed milestones. To start, the 1963 March on Washington—wherein the Revered Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech—marked its fiftieth anniversary in August of 2013. In commemoration, the NC NAACP planned thirteen simultaneous rallies against racism across the state.

The next month, in September of 2013, activists across the country paid tribute to the half-century that had passed since the murderous bombing of Birmingham, Alabama’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, a rallying site for Blacks who dared to protest widespread institutional racism in the South.

These two anniversary events happened to coincide with the passage of North Carolina’s controversial new voting bill, VIVA. And so Barber III, Reverend Barber’s son, was among the many NAACP leaders who seemed to intuit that therefore, a celebration alone would not suffice to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the next civil rights phenomenon on the calendar: Freedom Summer.

“It just made us young people in the NAACP think of the voting rights fights that are ongoing, as well as those that are new for our generation,” Barber III says. “Before that conversation, we had plans to commemorate Freedom Summer, but after VIVA passed, we decided we wanted to make sure we did something much deeper to honor it—we wanted to develop a campaign that could change and shape this state for the better, and also spark a new era of activism among young people.”

Barber III adds that because the Moral Movement itself was well underway by the time the NAACP youth division began recruiting Moral Freedom Summer organizers, he and his colleagues had already become well-versed in grassroots-style, fusion organization. For instance, they knew enough to be intentional about bringing in the next generation of “Freedom Fighters.” He explains, “We sought young North Carolinians who were interested in being on the ground, being in communities, doing deep voter registration, and making inroads within those communities.” These young people had to be willing to learn all about a given community’s individual struggles, they had to be equipped to listen to the needs of its citizens, and for the duration of 2014’s summer, they had to be willing to live with that community’s NAACP members and allies.

After all, Barber III explains, it’s the act of becoming entrenched within a community that equips an organizer to address the unique needs of its people, as well as its long-term infrastructure. “We didn’t want people helicoptering in for a moment and coming right out,” he says. “because that doesn’t work—that’s not what builds true community power.”

Highlander was where the NC NAACP began seeking pledges to make Moral Freedom Summer happen, and most collected funds were set aside for the young organizers’ summer stipends. Freedom Summer’s 1964 activists may have been volunteers; however, supplying payment for Moral Freedom Summer organizers, Zellner says, was a “very intentional decision.”

As someone who came of age in a pre-recessionary era embracing of unpaid internships as a stepping stone to one’s career, I find logic in the argument that those who can actually afford to take such apprenticeships are typically privileged.

“And that’s not representative of the future of North Carolina,” says Zellner. “We sought African American organizers, Latino and white organizers, women and men, religious and nonreligious organizers—a population that would actually reflect the state’s shifting demographics. Because as I’ve mentioned, this is not a Black-and-white thing—it’s a huge coalition being brought together to show how important and sacred the right to vote really is. And without payment, we wouldn’t have been able to assemble that kind of coalition.”

Freedom Summer organizers, conversely, consisted of unpaid kids who did in fact “helicopter in” to Mississippi—and this, too, was by design. Various SNCC chapters raised money to cover the volunteers’ food, training materials, and travel, but there was no actual payment involved. In fact, the very idea of Freedom Summer hinged on bringing in middle- and upper-class white outsiders—a demographic that ultimately accounted for about 70 percent of Freedom Summer’s more than one thousand volunteers.

SNCC speakers recruited on college campuses across the country, often drawing standing ovations for their dedication in braving the routine violence perpetrated by police, sheriffs, and others in Mississippi. Zellner says recruiters interviewed dozens of potential volunteers, weeding out those with a “John Brown complex”—a perception that their job was solely a white man's burden, or that they were in any way superior to those who they were helping—and informing those who did make the cut that their job that summer would not be to "save the Mississippi Negro,” but rather to work with local leadership to develop the grassroots movement.

At that point, lynching may have been the most dramatic consequence of voting in Mississippi, but it certainly wasn’t the only one. As James P. Marshall, a Harvard-based civil rights scholar and the author of Student Activism and Civil Rights in Mississippi: Protest Politics and the Struggle for Racial Justice (Louisiana State University Press, 2013), explains, “First you had the poll tax, which is of course designed to keep minorities and poor people away from the ballots. But even if you could pay that, if you were Black in Mississippi, they had other ways of keeping you in check. Your name would be published in the newspapers, and all of a sudden your credit might disappear, or you’d lose your right to work as a sharecropper, or your house would get shot at.”

Which is why SNCC worked so hard to attract educated, idealistic Northern kids. “Nobody knew or cared when another poor Black Mississippi farmer went missing or dead,” Zellner says. “But we knew that if there was a white victim of beating or murder at the polls, it would help to end press blackout in Mississippi.”

Which brings us to the secondary goal of Freedom Summer: media attention. At the time, only watchdog publications such as SNCC’s paper, the Student Voice, were covering civil rights activity in the Deep South. Zellner explains, “As long as there were just Black organizers and local Black people being killed in Mississippi, the mainstream press wouldn’t pay any attention—but if whites from middle-class homes got involved, sons and daughters of lawyers and congresspeople, then, we knew, people would tune in.”

It’s worth adding that the Deep South’s lack of media attention was colloquially known to many African Americans, Marshall says, as “press white-out.”

More than half of the citizens in Goldsboro, a somewhat isolated city of 36,437 in North Carolina’s central plain, are African American. Today, its citizens’ average household income is $29,456, and many, perhaps most, are employed by the local Air Force base. Goldsboro was a site of General Sherman’s historic Carolinas Campaign, an 1864 Union offensive. It’s also where Rebekah Barber grew up, and where she was assigned to wage her Moral Freedom Summer fight.

Rebekah, for the record, wasn’t even eligible to vote in 2010, for the prior midterm election. “But I saw all the facts,” she says. “I know that the reason we’re facing some of the problems we are now—why we have such a regressive legislature—boils down to the truth that in that election, people didn’t vote like they should’ve.”

Rebekah adds that she is “the type that tries not to make the same mistake twice.” While she grew up in a household of activists, and was raised by he who is arguably this generation’s preeminent civil rights leader (as well as the top faith leader to watch in 2014, according to the Center for American Progress), Rebekah Barber shies away from the term organizer, saying “I don’t know exactly where my future will lead. But I understand that people fought and died for my right to vote, and so exercising that right is the least I can do, the least everyone can do. But I don’t mean to make it sound so simple, because we have to do our research before we go out to the ballot box.”

And research is what she brought to the denizens of Goldsboro, in the form of easy-to-read fact sheets breaking down the Tar Heel State’s recent extremist legislation, and the implications of such measures for its average citizens. “As far as being informed,” she says, “people in North Carolina generally know things are bad lately, but it’s a lot different when you actually have numbers in front of you.”

Each morning last summer, she’d link up with at least one member of the city’s local NAACP chapter, go out into the community, and canvass, “just like they did fifty years ago.” While Barber’s training at Bennett College may not have included comprehensive beating and tear-gas training, each Moral Freedom Summer organizer had to pledge never to go out alone, never to go out at night, and always to phone local NAACP chapters and their partner organizations to report their whereabouts. Most days, Barber would stick to residential areas, and travel door to door, striking up conversations with citizens, and offering to help them register to vote.

“When you show up in person, you also show that you actually care,” Rebekah notes. “It’s easy to say ‘Go vote!’ from a distance, but taking the time to talk about it, and putting a human face to the NAACP and the Moral Movement? That makes a huge difference.” Oftentimes, those front-door interactions were just quick conversations—or instances of someone stating that they were already registered to vote, thank you very much—but at least a few times a week, the soft-spoken-but-assertive Rebekah would find herself pointing to the meat of the matter.

“We’d remind them of people who fought and died for our right to vote in Freedom Summer and beyond,” she says. “In some areas, we’d ask people whether they had access to the Internet, or to sample ballots, all the while knowing that the answer was ‘no’.”

And, she says, many citizens she spoke with knew that they were being affected by Medicaid cuts—which was also the issue that Rebekah says resonated most among those with whom she spoke while canvassing—or by the loss of their unemployment insurance. However, they didn’t know quite why. “Until they know why they’re just angry,” Barber says, “but once we show them the specific legislation and they come to understand the why, they’re typically more motivated to at least try to change things.” She likens this phenomenon to her own experience of learning that her college tuition was increasing. “It was frustrating, but I didn’t understand why it was happening until I read about how [North Carolina Governor] McCrory’s been turning away public funding.”

On many other days, Sundays in particular, Rebekah and her NAACP copilots would hit up church or community meetings and introduce themselves. “We really wanted to stay true to the Freedom Summer model, and make sure we actually went out into the community,” she says. “I mean, sure it was my hometown, but I’ve never been entrenched in any community like that before in my life. That impact of that level of involvement is hard to explain—it was just so amazing.”

While the majority of Freedom Summer volunteers may have been white, Zellner says the success of Freedom Summer 1964 rests on Black Mississippians. “They were the ones welcoming us into our homes, feeding us meals, letting us sleep on their beds, and trusting us to educate them about their rights as citizens.”

Freedom Summer volunteers were dispatched to Mississippi’s poorest and most rural communities. Once they arrived, volunteers seeking housing would typically go to Black churches. And locals’ hospitality, Zellner says, was astounding—especially considering the fact that, once area supremacists got wind that these Blacks were harboring “outside agitators,” they’d often receive intimidating phone calls. It was standard practice of Klansmen in 1964 to threaten to bomb or burn these citizens’ homes down.

“I’d go to the old Black women who were taking me in, and the old Black men who vowed to help protect us, and ask why they would do it,” Zellner recalls, emotion searing his usually garrulous voice. “I’d say, ‘How can you take me, a Southern white man, and forgive me for what we’ve done?’ But these residents, most of them God-fearing Christians, they would just point to the social gospel. Many would say, ‘Hate is a poison that corrodes the container it’s carried in, so we can’t hate—not for our own spiritual well-being.’ And I’d wonder, why couldn’t all those bible-thumping white Mississippians and Klansmen harbor the same philosophy?”

It’s difficult to describe a “typical” day during Bob Zellner’s 1964 summer. The then twenty-seven-year-old spent the first few weeks accompanying Michael Schwerner’s wife Rita all over the state, following his, Chaney’s, and Goodman’s then-mysterious disappearance. For at that point, the Civil Rights Movement still hadn’t gained much support from federal law enforcement.

“Their bodies weren’t found until much later in the summer, so Rita was doing everything she could to piece together the disappearance,” Zellner says. To try to get help, they intercepted a conversation between Alabama governor George Wallace and Mississippi governor B.J. Johnson—who, once he and Rita introduced themselves, bolted for his governor’s mansion and locked the door. They then traveled to the Oval Office to demand that LBJ send five thousand federal marshals to Mississippi to help locate the missing civil rights workers.

A couple of weeks later, the FBI opened its first-ever field office in Mississippi, dispatching two hundred agents to search for the missing men. “During that search, they uncovered the bodies of several maimed Black men,” Zellner says. However, it wouldn’t be until August of 1964 that the feds would surmise that the three vanished civil rights workers had been hauled off to jail, and subsequently released to local KKK members—including the deputy sheriff of Neshoba County—and taken to an isolated spot where they were shot and killed, and then buried deep in an earthen dam outside Philadelphia, Mississippi, on a property known as Old Jolly Farm.

For the remainder of the summer, Zellner resided with Black families in Greenwood, Mississippi, a delta cotton town of about ten thousand, where Civil War-era planter culture was still embraced, where city police had been known to sic dogs on Blacks registering to vote, and where SNCC had moved its headquarters for the summer of 1964. There, Zellner served as Freedom Summer’s project manager—more or less the same role that William Barber III, Reverend Barber’s son, held throughout Moral Freedom Summer.

By that point in 1964, Freedom Summer volunteers were concentrated within twenty-five different areas across Mississippi. The civil rights workers, as well as the Blacks who sheltered them, had collectively weathered more than thirty bombings and about eighty attacks. Part of Zellner’s job was to oversee the area’s Freedom Schools—coordinating book drives in the North, and ensuring that volunteers had plenty of training materials.

“The students were most astounded by their own local Black history,” Zellner recalls, “or at least, the unvarnished view of it we tried to provide. They’d never been taught Black history, didn’t know there was any—they were just voracious to read about it. So midsummer we organized a bunch of additional book drives, arranged for students from Harvard and Wellesley to send more history books down by the truckload.”

Another role of Zellner’s involved organizing tests of the public accommodations portion of the just-enacted Civil Rights Act, passed in July 1964, which legally integrated public spaces. Not shockingly, Mississippi whites were resistant to the many trials that involved Freedom Summer volunteers and local Black youths setting up mixed-race shop in theaters and restaurants. “Every day, we had plenty of troubleshooting to do, rescuing people from mobs, bailing folks out of jail—there was never any lack of work at hand,” Zellner says.

During the hundred-plus-degree dog days of that summer, Zellner also witnessed a truck full of Confederate-flag-waving whites bringing a monkey to a voter registration drive, there to have it stand in line with many of Greenwood’s African Americans. One night, he brought a critically wounded Black gunshot victim to the hospital, only to have the patient turned away and refused first aid, the “colored doctor” being off duty that day. But, he also saw local people empowered for the first time with the knowledge that they had rights, they had history, they had something to stand for, and they had a legal, if not easy, means to do it.

“The summer of 1964 was a life-changing experience for all of the volunteers who came down,” Zellner says, “even for us veteran staff people, who’d already done plenty of protests and jail time and freedom rides and sit-ins. Because this was about becoming ingrained in a community and working with its locals. People were changed forever in Mississippi—locals and volunteers alike.”

While many Moral Freedom Summer fighters set up camp in “freedom houses”—a term borrowed from Freedom Summer of 1964, that in 2014 denoted spaces donated from or shared with local NAACP members—Rebekah Barber spent the summer of 2014 in her childhood home, with her family. She was also able to corral old friends into helping her, and to get those friends to distribute flyers reading, “JOIN THE MORAL MOVEMENT AND STAND UP FOR EQUALITY, HEALTH CARE, FULL FUNDING FOR EDUCATION, A LIVING WAGE, ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE, AND VOTING RIGHTS FOR ALL NORTH CAROLINIANS.”

Most of the people she encountered during her canvassing, Rebekah says, were “very respectful.” She experienced some powerful interchanges that involved sitting down on various front porches and helping illiterate citizens navigate their voter registration forms. “Nineteen sixty-four showed us that while many citizens may have been illiterate, never granted their right to an education, they still desired to have their voices heard,” she says.

But unlike what organizers experienced in 1964, Rebekah Barber encountered no violence, zero monkeys, no name-calling, nor tear-gassing, nor jail. There was one old man, however, “an older white gentleman,” who tried to rile her up one humid July, 2014 afternoon, when he came across the voter registration table she’d set up in the parking lot outside Goldsboro’s Wal-Mart.

“He started making a scene, accusing me of registering swarms of illegal immigrants,” Rebekah says. “He kept shouting at people in line that they needed to travel up to the board of elections if they wanted to register, so that if they were ‘illegal,’ they would get caught.”

Rebekah tried her best to explain to this man that not everyone has that opportunity, citing economic barriers like lack of a vehicle, or inability to take time off from factory or housekeeping work to visit the government center during working hours. “So then he tried to question my validity, grilling me about who my senators were, et cetera,” she says. “I don’t think he thought I would know that information. He eventually retreated, silently.”

Rebekah Barber is well aware that, compared to the experiences of Zellner and his Freedom Summer compatriots, her cohort’s efforts were peaceful and marked by ease. “Some days could get exhausting, and some people would be rude or abrupt or claim they ‘had their own reasons’ they didn’t want to register,” she says. “I knew I certainly couldn’t force everyone. But when it got hard, I’d just stop and think about all they went through in 1964 and consider how we don’t have anything to worry about. The biggest peril today is not violence; it’s becoming disenfranchised, and that just fueled my Moral Freedom Summer mission.”

By many measures, Mississippi remains America’s most repressive, impoverished, and uneducated state—1964’s Freedom Summer did not by any means not transform it into a bastion of acceptance and enlightenment. Nor did it register more than twelve hundred voters. However, the national outrage over its grim murders did help to procure support for Congressional passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It also garnered the national publicity that SNCC was so desperately after.

It would be a vast distortion to paint brutal murder as a bittersweet price to pay for media headlines. Yes, major, nationwide papers and networks did indeed tune in to the mystery during those forty-four days spanning Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney’s disappearance and their bodies’ discovery. But by that point, many had been following Freedom Summer already—and this can largely be traced back to Harvard’s afore-mentioned James Marshall, a fellow at the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Let’s circle back to the issue of 1960’s-era press blackout for a moment: Marshall, a twenty-three-year-old Yale student on leave in 1964, didn’t actually go down to Mississippi as a volunteer, but many of his classmates did. And as a fervent civil rights supporter and a staff member of the Yale Daily News, Marshall saw a key opportunity to boost the Mississippi Freedom Summer project. “I was aware that there would be a problem getting the information out,” he says, “which has always been the case for civil rights activities.”

Beginning during the period of 1963’s “Freedom Ballot,” and working through Freedom Summer and beyond,” Marshall would have his friends and contacts within SNCC and other student leadership organizations call him at night and tell him about their days. “I’d get those stories’ galleys ready by around twelve at night, and then shop the stories around the Ivy League papers through our wire, the Collegiate Press Service,” Marshall says. If there was a big story, he’d relay it the Hartford Courant and they’d take it from there, making inquiries with the local press in Mississippi, and often getting such hooks picked up by the national wire services. “I racked up a huge telephone bill getting all those dictated accounts down,” Marshall recalls.

After the summer of 1964, he went to New York City to work within the community relations department of the Congress for Racial Equality, better known as CORE, doing, he says, “essentially the same thing.” Nowadays, Marshall’s back in action, working to get the Moral Movement what he says is its due attention. After all, the NC NAACP certainly isn’t hoping to bank on high-publicity violence.

Before Marshall’s old friend Zellner got him looped into the NAACP’s press release circuit, late in 2013, he says none of Harvard’s many civil rights professors even knew about the now ten-year-old Moral Movement. Nowadays, he blasts weekly or twice-weekly missives about it to hundreds of Northeast-based academics, SNCC veterans, and progressives from around the country.

“The experience I had with the Civil Rights movement in sixty-four had a very large influence on why I became involved with the Moral Movement in North Carolina,” says Marshall, “because I’m doing the exact same thing again.”

Slowly, the “Moral” word is spreading, with organizations like MSNBC and Crisis Magazine beginning to devote coverage to Barber and his contagious, grassroots model of organizing. But considering it’s the largest such movement of this century, it is indeed curious that outlets such as the Washington Post, Wall Street Journal and CNN have stayed relatively mum on the South’s widespread moral combat.

“It doesn’t behoove right-wing organizations, which control so much of the news, to let the truth come out,” Marshall posits. Zellner adds, “Grassroots organization is scary on a national level. They’re afraid of it. Because when you show people how simple it is, the power it has, you realize it’s not controllable. And as movements like Moral prove, grassroots action is infectious. It’s fusion—it applies to any group that feels oppressed or disenfranchised.”

Luckily for the Moral Movement, it was born in an age where mainstream press isn’t strictly necessary. “We’ve got every Moral Monday live-streaming on YouTube,” Barber III notes. “We’ve got powerful pictures all over social media—and people standing in solidarity by tuning in on a consistent basis. So slowly but surely, the word is getting out.”

Not unlike Freedom Summer, the Moral Freedom Summer campaign fell short of its registration goals, netting only about fifteen thousand new voters. While the NC NAACP’s original goal was to amass 50,000 new citizens to join its “Moral March to the Polls,” the campaign certainly isn’t considered a wash. For in many other ways, Moral Freedom Summer exceeded benchmarks put in place back during the Greensboro training session.

At first glance, Moral Freedom Summer seems to be an emotional campaign. My initial impression was that of a loftily titled, avant-garde homage to a civil rights milestone—a skillfully choreographed if esoteric gesture. But I’ve since learned that William Barber III is too shrewd of a planner, being outspoken about the fact that the success of any grassroots organization rests on meeting specific benchmarks. So for him, the Moral Freedom Summer campaign boiled down to a number of metrics.

A Moral Monday protest occupies the NC General Assembly building.

“Qualitatively speaking, we did seek a resurgence of energy, and awareness about what was happening in North Carolina, among young people,” he says. “We wanted to establish intergenerational relationships, to bridge relationships between elders, social movement veterans, and youths. It’s a fact that young people tend to sit out during midterm elections, and we wanted to shift that for the long term, to drive home an understanding that every election is critical for all citizens.”

Quantitatively though, the measure of success gets less symbolic. “We aimed to inspire at least two hundred fifty ‘people’s coalitions’ within individual communities,” Barber III says, “and we actually exceeded that, seeing about five hundred of them.”

Like the NC NAACP’s pilot people’s coalition, Historic Thousands on Jones Street, or HKonJ, these phenomena involve people mobilizing peaceful rallies and demonstrations within their own communities. One such event I attended in Wilmington involved hundreds of demographically diverse citizens cheering for their high-profile visitor, the booming and ever-magnetic Reverend Barber. The fifty-one-year-old delivered a rousing speech about the need for North Carolina’s citizens to prevent further “moral” backslide, which culminated in an audience explosion of hugging, tears, Stevie Wonder songs, and the formation of a massive line of people, eager to personally receive three voter registration forms—“one for you, and extras to register two of your friends”—from the famous reverend himself.

Another pre-election goal they exceeded, says Barber III, was that of amassing eight to ten “massive statewide actions, modeled after Moral Mondays themselves.” What’s perhaps most impressive of all, though, is the fact that rather than just meeting the expected two thousand door-to-door and phone bank contacts, the average Moral Freedom Summer fighter made fifteen thousand such contacts. “And for a number of these organizers, this was their first time actually organizing,” Barber III says. “So while the lofty goal of fifty thousand registrees was not made, it was made up for in plenty of other elements of the work.”

To the NC NAACP’s great disappointment, less than three million of North Carolina’s 9.85 million citizens voted on last November 4. “It’s easy to get depressed when some eighty thousand African Americans still didn’t turn out to vote,” Barber III says. “We didn’t necessarily see a lot of the things we were hoping for.”

While Rebekah Barber notes that it’s unlikely that Moral Freedom Summer will be a repeat phenomenon—“The Moral Movement is designed to evolve from year to year, meeting different needs at different times”—her brother William III certainly doesn’t consider the campaign any kind of failure.

“When you look at voter turnout you have to understand that first of all, what we were aiming to do actually happened—more young people participated in a midterm election here than we could ever remember happening; and number two, we can see that despite all the voter suppression that’s been enacted—all the propaganda pushed out, all the record-setting amounts of big money funneled into this state—the margin of right-wing victory was actually a very small percentage. And that gives us hope. Because if those leaders actively trying to suppress the vote can pull out all those stops and still only win by a tiny percentage, there’s still plenty of hope for us to be able to continue to mobilize, to go back into our communities, and to push people to vote.”

James Marshall is quick to add that, after an election like the 2014 mid-term, “There’s always a collapse, morally and psychologically. But this just goes to show that it’s time to wake up.”

Having been born and raised in Chicago, and having lived in major cities in Texas, the Czech Republic, and California, I can say with certainty that North Carolina is far from politically apathetic. In the wake of the 2014 election, strategy for 2016’s race is a pervasive topic of conversation among my neighbors and colleagues.

In terms of the effect the Moral Freedom Summer initiative had on the organizers themselves, Zellner deems it a rousing success. “We need a new generation of revolutionaries in the South,” he says, “especially the way things are going during this unpredictable third wave of Reconstruction. Freedom is a constant struggle, and many of us who have been organizing and fighting for it for our whole lives won’t be around in another twenty years.”

Zellner, who says Reverend Barber’s prowess and magnetism as a leader rivals that of MLK, believes the Moral Movement is here to stay—“It’s become a model for grassroots organizing in the South and beyond, and it will probably be relevant for the next quarter of a century.”

After all, one of Reverend Barber’s favorite and, as of late, most often repeated rallying calls is this: “It’s a movement—not a moment.”

Katie O'Reilly is a writer and reporter whose work has appeared or is forthcoming in Vela Magazine, Buzzfeed, Bustle, The Onion/A.V. Club, The Huffington Post, Texas Monthly, and NPR. She is the managing editor of Ecotone, a place-based literary journal, and previously worked as a public radio reporter and as the managing editor of DAYSPA magazine. She graduated from Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism in 2007, and is currently a candidate within the University of North Carolina Wilmington's creative writing MFA program.