by Kwame Somburu

February 21, 2015

Malcolm X was a unique person. His transition from Malcolm Little to the internationally renowned Malcolm X–with the development in his final years of uncompromising opposition to all forms of national/international oppression, exploitation, and discrimination–is truly exceptional.

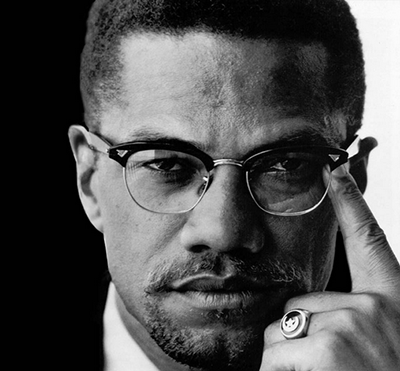

Malcolm X.

Malcolm was never a criminal. Instead I see the anti-social behavior of his early life as being the result of his victimization by the most criminal, inhumane, hypocritical, ruling class and society that has ever existed. The Nation of Islam was significant to his positive early development. I saw and heard Elijah Muhammad three times along with many other N.O.I. ministers, and read every word in the weekly issues of Muhammad Speaks for over two years. In addition I attended many meetings at Temple #7 in Harlem.

I was attracted to Malcolm’s intellectual curiosity, humanity, and rapidly accumulated knowledge of diverse and varied types of social injustice worldwide. He was seeking to tell the unvarnished truth and expose the basis of structural inequality. He felt that was the first step in the fight for the true liberation of African Americans, and later, as he became a person of the world, for liberating all of humanity. Knowledge, unity, and militant determination were key to transforming a brutal society into its opposite.

Malcolm exemplified a unique intellectual curiosity and continuous and total commitment to fighting against all forms of oppression and discrimination. When that was no longer possible inside the N.O.I., he was forced out over his remarks following President John F. Kennedy’s assassination about the “chickens coming home to roost.” He began to build the Muslim Mosque, Inc. as well as the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

Malcolm’s travels to Africa and the Middle East had a profound influence on him. They expanded his vision and deepened his class consciousness. He stood resolutely against colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism. Speaking at a Militant Labor Forum panel hosted by the Socialist Workers Party on May 29th, 1964 just following his return from Mecca, he gave a speech that is known as the “Blood Brothers.” His talk was a response to the supposed existence of a Harlem-based hate gang that was to kill whites. Malcolm discussed this imaginary gang in the context of what he had learned in Africa of how colonialism repressed people, and called the police in Harlem an occupying army. He connected racism to capitalism, commenting:

Most of the countries that were colonial powers were capitalist countries, and the last bulwark of capitalism is America. It is impossible for a white person to believe in capitalism and not believe in racism. You can’t have capitalism without racism… And if you find one and you happen to get that person into a conversation and they have a philosophy that makes you sure they don’t have this racism in their outlook, usually they’re socialists or their political philosophy is socialism.

I was in attendance and was able to speak for two minutes about the work of the Harlem section of the Freedom Now Party (you hear my remarks about 35 minutes into the YouTube video). At that time (and until 1979) my name was Paul Boutelle and I was chairman of the party’s Harlem section. (In August 1964 I was banned from speaking publicly in Harlem, and was arrested for attempting to speak as the party’s candidate for State Senator.)

Later in 1964, Malcolm X returned to Africa, where he spent 19 weeks in travel throughout the Middle East and Africa. He returned less than three months before his assassination. During his travels, Malcolm X saw that the countries in Africa that had just gained their freedom were rejecting capitalism and turning to socialism. He saw that as a favorable development. His homecoming rally on November 29 at the Audubon Ballroom was a report on the change taking place in Africa. Introduced by Clifton DeBerry, the 1964 SWP presidential candidate, he announced, “This is the era of revolution.”

The most criminal ruling class that ever existed soon realized that Malcolm must be eliminated before he became instrumental in developing a revolutionary movement that democratically represented “we” not “I.” When I came to the Audubon Ballroom on the afternoon of February 21, 1965 with my son, I noticed there was no police presence. In fact, I remarked to one of the security guards about their unusual absence. Just after Malcolm came onstage, with about 400 present in the ballroom, a tussle broke out near me. I heard someone say, “Take your hands out of my pocket.” While this diversion was being acted out, and security guards drawn toward them, a smoke bomb went off and Malcolm was shot multiple times.

Only Talmadge Hayer, beaten by a crowd outside the ballroom, was taken into custody and booked. Another man was put into a police car and taken away. Who was this second person? In an interview, Police Commissioner Michael Murphy (who had previously made vicious statements about Muslims) talked about two men being taken into custody. This was mentioned in the first editions of both the New York Times and the New York Post, but subsequent editions talk about one man in custody.

Like many others in the room, as soon as I had heard a gunshot, I grabbed my son and ducked down. Even amidst the confusion, many sensed that Malcolm had died. Later the medical examiner counted 21 wounds from three different guns.

In his eulogy, Ossie Davis called Malcolm as a “shining black prince.” At the time of the murder, Malcolm’s revolutionary views were still evolving. He probed the depths of U.S. racism, linking the struggle to overcome discrimination to an international struggle for human rights and liberation, particularly as it was developing in Africa and the Caribbean, and inspired political activists, poets, and musicians.

Kwame Somburu has been a “Scientific Socialist” since 1960. He was known as Paul Boutelle from 1934 to 1979, and Kwame Somburu since then.

Comments

One response to “On the 50th Anniversary of the Assassination: Malcolm X in Life and Legacy”