by Dennis O’Neil

March 27, 2017

The reverberations from the death of Chuck Berry are starting to subside. The news naturally had the greatest impact on people of my generation, Boomers, for whom he is an inextricable part of the soundtrack of our lives, while many young ‘uns are wondering what the big deal is.

Plenty of critics and pundits are ready to fill them in, of course. And unsurprisingly, their memorial articles tend toward what my friend Yolanda M Carrington calls “Berry-as-colorblind-god tributes from mass media.” He is rightly hailed for his ability to tap into the psyche of the recently invented “teenager “ (implicitly white), and rock and roll’s considerable contribution to the breakdown of the color line in popular music. (Minimal or missing mention of his record of exploitative, and sometimes criminal, sexual practices has been another part of the posthumous canonization process.)

Chuck Berry is proclaimed an avatar of American culture–a postage stamp is doubtless in the works as you read this. And as with any dead Black pathbreaker, political as well as musical, the rough edges are hastily being sanded down. If they can make Malcolm X an avatar of racial unity, Chuck Berry should pose little difficulty.

I want to poke a hole in this guff. Please give a three-minute listen/looksee to this live video of one of his most iconic tunes, “Promised Land.” This is many people’s favorite of all his songs, and it has been covered by big time artists like The Band, The Grateful Dead (who played it live 425 times!) and, of course, Elvis Presley. It is generally treated as a celebration of America itself as the promised land, with the fact that Berry kyped the melody of the hillbilly classic, “The Wabash Cannonball” for it cited as proof.

This is an overbroad and, frankly, white reading. The song is the story of the Poor Boy, a young Black man who grabs a Grey Dog seeking to get the hell out of the Jim Crow South. He runs into trouble several times and it is only family and community that let him complete his journey. As soon as he makes it, the Poor Boy immediately places a long distance call to kin back home.

The real story is in the second verse:

We had a little trouble that turned into a struggle

Halfway across Alabam’

And that ‘Hound broke down and left us all stranded

In downtown Birmingham

This was written only a couple years after the Freedom Rides, the second stage (after the lunch counter sit-ins) of the student-led desegregation struggle in the South. Black and white activists rode interstate buses through the segregated South and met savage reprisals. The first Ride, on two buses, started on May 4, 1961 and made it through Virginia and North Carolina okay, but was attacked by a big-ass armed lynch mob, and one bus was firebombed, in Anniston, AL. (Armed Black citizens led by Colonel Stone Johnson rescued the badly injured Freedom Riders from a local hospital and shuttled them to safety.)

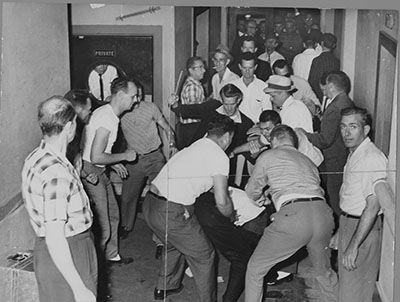

Freedom Riders attacked in Birmingham.

The second bus was permitted to continue to Birmingham after the Freedom Riders on it were also savagely beaten in Anniston. There they were met by a racist mob organized by the KKK and Police Commissioner Bull Connor which laid into them with baseball bats, pipes and chains. This was the attack that made national news, so the menace in the words “left us all stranded/ In downtown Birmingham” is unmistakable.

Why has this bit of political/musical history not been mentioned in the standard-issue Chuck Barry obituary? In his autobiography, he details the origin stories of many of his songs, but not this one. The most obvious answer is that the recorded version, the 1964 single, renders the first line of the verse “we had motor trouble…” Perhaps Chuck Berry or his label owners, the Chess brothers, were toning things down a bit for the sake of radio play. It is also worth mentioning that all of the major white cover versions I mentioned above retain the lyrics from the record, turning the song into one about upward class mobility, especially when sung by an actual white Southern poor-boy-made-good like Elvis.

But Chuck Berry didn’t forget. Every live version I could find has him singing “We had a little trouble that turned into a struggle/ Halfway across Alabam’.” No mention of engine malfunction. And that struggle by young Black and white activists continued for months though summer and fall of 1961, through scores more Freedom Rides and over 300 arrests that forced the Kennedy administration’s Interstate Commerce Commission on December 1 to order the desegregation of all interstate buses, trains and terminals. The “Whites Only” signs came down.

Dennis O’Neil is a retired postal worker, a founding member of the Freedom Road Socialist Organization, and an occasional DJ.