Bill Resnick

October 18, 2018

On July 14th 2018 the The New York Times reported that holding facilities for immigrant children separated from their parents were enforcing a “no touching” policy: children, even siblings, were not permitted to hug, hold hands, or touch one another in any way. It quoted a 9 year old girl not allowed to touch her baby brother. A Washington Post report quoted one staff worker in a toddlers room who had failed to calm a distraught child. The worker explained that she couldn’t console the child because we’re “not allowed to touch the children.” Widely covered in media, a big story for a short time, it triggered a great public outrage that forced the administration to temporarily retreat.

The whole episode is quite revealing. One of its lessons is well known, the thoughtless depravity of Trump and his agencies and their baleful impact on public services. The other amounts to a revelation, less appreciated but profoundly encouraging especially for the left. For the episode demonstrates a transformation of child rearing values and practices over the last century, part of a broader democratizing movement in U.S. social life, with a long way to go.

What does this episode tell us? Part 1: The Depravity of Trump World

The no touching rule, which came from the top of the Federal immigration apparatuses (No one seems to be taking responsibility) amounts to child abuse. A considerable body of research documents that children, particularly the youngest, deprived of physical touch are diminished in every capacity — physically, emotionally, and intellectually. In early studies so cruel they can’t be repeated, “Harlow’s monkeys,” well fed but deprived of maternal warmth and touching but given a generous piece of terry cloth to cling to survived but proved unable to form bonds with others and engage in social life. Those fed by a wire figure without any cloth engaged in behavior that resembled acute human psychosis. As to humans, researchers have studied younger children including infants confined in orphanages and other institutions who received sufficient nourishment but little attention from the few staff. The children, particularly the youngest, fared very poorly, most demonstrating what physicians now call failure to thrive (stunted growth, depression and deficient language development).

This is now common knowledge, and there’s hardly a writing or video for expectant parents that doesn’t emphasize the importance of warm, comforting, soothing touch. If a public child welfare agency, after examining the infant and talking to the caregivers, had good evidence that the caregiver was not touching or comforting the child (perhaps having read a not so ancient text that holding and fondling the child created excessive neediness and dependence), it would have little choice but to remove the child from the home until the parent established that the initial judgement was wrong or demonstrated commitment and capacity for adequate parenting. (This is of course not to say that the understaffed, underfunded, racist and classist welfare agencies are adequate to their mission, but that is a matter for another article.)

Though the no touching rule was indisputably child abuse, lower level officials of the agencies and the leadership of the holding facilities did not challenge the policy. Indeed, they obsequiously obeyed (though some staff did resign). As to state and local child protection agencies, there is no report that they acted either by warnings to or by opening investigations of the holding institutions, though the acts of federal workers or contractors, even in their official capacities, are not immune from state child welfare laws.

When this Trump World atrocity was exposed, it ignited a firestorm of condemnation from the public. The ACLU challenged in Federal court, the judge quickly ordered that the children be reunited with a parent. The Trumpies did not appeal and told their various agencies and contractors to cooperate in reuniting the families.

Still the torture of these children and families continues. In their haste, indifference, and racism the agencies failed to keep records of the names of the family members and where they were sent. In addition, the administration began, when families were reunited, to send them back to the countries they fled. This also led to legal challenge though less public protest. And in early September the administration sought to modify a judicial settlement so that it would allow indefinite detention of whole families including those seeking asylum. And at the time of this writing, they are considering a policy of reuniting the child and parent, if they agree to leave the country.

This is another demonstration of the depravity, repressiveness, and racism infecting the higher reaches of this country, and the intimidation fear, and demoralization within the public agencies and private organizations that carry out policy, that obey orders. Those promulgating the policy were quite willing to torment parents and children—parents with grief and worry, children with debilitating deprivations to discourage border crossing.

What does this episode tell us? Part 2: The Hardly Appreciated Transformation of Parenting

This episode reveals another story, that’s important and hopeful, about a sea change in public values and social practices, to be found in the public outrage that the anti-immigrant cruelty generated. To be sure, the intensity of the outrage over children and immigrant torture arose out of a gut recognition of the consequences, the fear and terror, of no touching of babies. But this is not a standalone sentiment. Rather it reflects a transformation in popular understandings and practices as to child rearing.

Corporal punishment of children has greatly declined and child abuse death greatly reduced at every class level. Only in the late 1980s were physicians and hospitals required to report suspected child abuse and only at the end of the century were they required to meticulously investigate every child death, including full body X-ray to find multiple injuries. From the 1960’s to today child death has declined by 75%. Much of this decline is the result of car seats and better access to health care, but, recognizing that previously death from injuries was not investigated, it appears that there has been considerable decline in lethal abuse as well.

Further, alternatives to violence have been popularized and are now practiced across the class spectrum. As to “Spare the rod and spoil the child,” it has been replaced by efforts at patient “positive discipline.” “They should do what they’re told” and “Children should be seen and not heard” has been replaced by “use your words” and often ridiculous and premature strategies to build literacy. And as children develop, parents offer more and more “choices,” that to help the child see herself as an independent decision maker. And children are being involved in family decisions as their growing capacities warrant, that in order to develop their capacity to evaluate options, weigh evidence, and make intelligent choices.

To be sure these efforts take a lot of energy and lead to great frustration and often in retrospect high comedy. Still the change is fundamental, a rejection of the wisdom dominant from the late 19th Century and still influential through mid-20th century. Today anyone seriously advising that even the youngest children should be taught regularity and discipline as part of a process of “breaking their wills” would be seen as deeply misguided and troubled.

Of course the learned and professional occupations take credit for leading the popular classes (seen as authoritarian and lacking the higher virtues) to modern parenting. In fact this transformation, to be sure a long process with a ways to go, was the product of the popular classes, confident in themselves, their unions and political party having guided the country out of the great 1930s elite created Great Depression and to victory in World War II and prosperity at home. Having fought in and won WWII, marrying like mad and forming families, this working class decided en masse to not be Nazis to their children.

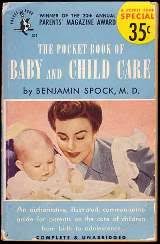

In 1946 they found the advisor and advice they wanted in a really cheap book that hooked them in the first pages telling them to “Trust themselves.” It was written by an obscure physician, Dr. Benjamin Spock, who in long evenings after practicing medicine at home-front Navy bases during the war, wrote a book that he named A Common Sense Guide to Baby and Child Care. Eulogized by Time Magazine as the man who “singlehandedly changed American child rearing,” he came back East after the war and sought a reputable publisher. All rejected it, their experts finding it completely out of step and dangerous. In desperation Spock turned to Pocket Books, then a small press now seen as the U.S. pioneer of mass market paperbacks. They gambled to print 20,000 copies, on newsprint with a thin cardboard cover, a few stick figure illustrations, and to sell it on newsstands for 25 cents (even then cheap) and without advertising.

In 1946 they found the advisor and advice they wanted in a really cheap book that hooked them in the first pages telling them to “Trust themselves.” It was written by an obscure physician, Dr. Benjamin Spock, who in long evenings after practicing medicine at home-front Navy bases during the war, wrote a book that he named A Common Sense Guide to Baby and Child Care. Eulogized by Time Magazine as the man who “singlehandedly changed American child rearing,” he came back East after the war and sought a reputable publisher. All rejected it, their experts finding it completely out of step and dangerous. In desperation Spock turned to Pocket Books, then a small press now seen as the U.S. pioneer of mass market paperbacks. They gambled to print 20,000 copies, on newsprint with a thin cardboard cover, a few stick figure illustrations, and to sell it on newsstands for 25 cents (even then cheap) and without advertising.

The gamble paid off, a colossal understatement. It sold out in the first month, and they printed more and distributed more widely, but couldn’t keep up, edition after edition, becoming second to the St. James Bible in U.S. books sold. And to this day never advertised. It was all word of mouth, parents telling parents, though some mouths have bigger audiences. On TV’s biggest hit of the time, “I Love Lucy” ( half the TV sets in the country would watch its episodes), when Desi Jr. was acting up, Desi would tell Lucy, “Get the Spock,” a laugh line for an audience to whom Spock had already become a household word).

Pocket books was making untold millions and other publishers and experts got into the act, many more nimble than Spock, more attuned to the changing values of the people having babies, who were looking for direction and buying books and then videos. If Spock provided the vehicle for the popular classes to express and live their values, another previously obscure professional, Diana Baumrind, also with an elite credential (she taught at UC Berkeley) provided the theoretical foundation for the whole child rearing advice industry in her typology of child rearing methods.

In 1966 Baumrind hypothesized three styles – “permissive,” “authoritarian,” and “authoritative.” She found fault with the first two, and offered her model of authoritative parenting, that featured loving supportive interactions and also firm standards and guidance when necessary without creating unnecessary restriction. The parent encourages verbal give and take, shares with the child the reasoning behind policy, and solicits objections when the child balks at conforming. Initially emphasizing firm but fair and communicative parenting, Baumrind’s later writing advocated joint decision making and democratic values.

In time, driven by popular demand, expert advice so changed that Spock (a benign patriarch who only began referring half the time to children as “she” in the 1976 edition, after years of prodding by feminists) was left way behind.

Authoritative child rearing became and remains the central concept and goal of pretty much the whole spectrum of child rearing advice books that gain an audience. Indeed even conservative writers like John Rosemond and the pamphleteers of Focus on the Family (the go-to site for evangelical Christians) are now to the left of the 1946 Spock on matters of when to begin toilet training, when to resort to spanking, and involving children in family decision making. Though conservatives still rail against that permissive Spock.

This democratizing transformation of parenting is no trivial “cultural” development. Of all the big decisions in working class life – as to education, work, politics, and family – the values and practices of parenting are probably the most considered and least constrained by the social, political, and economic conditions of the world. Further, an argument can be made that the liberatory, democratizing, and nurturant thrust, so visible in child rearing, radiated across social life, indeed across all power and authority relations, including our current system’s abuse of nature. Which generated the many movements associated with the 60s and the whole ensemble retains the initiative today. Of course, in every sphere defenders of the old order, at first shocked, responded with considerable opposition, in many areas, like gender/sexuality, the workplace, the environment, and especially race, their counterattack has been furious, sustained, and dangerous.

These nurturant democratic yearnings, and the practices and the struggles that arose from them, have profound political significance. Previous periods of major re-composition powered from below, even those that seemed to be sudden eruptions, have been the product of considerable social/cultural development.

If these hypotheses have merit and if today’s period of perpetual crisis becomes critical, requiring intensive comprehensive care, aka dramatic reconstruction of economy, society, and state, aka revolution, then movements from below might coalesce around a radically democratic program and will not likely be derailed by pervasive racial, religious, and gender antagonisms. How a left can operate to advance this possibility deserves much attention.