an interview with James Kilgore

January 2, 2015

Against the Current: Mass incarceration has suddenly gotten quite a lot of attention in the media and in the political mainstream. Why has it become a high profile issue all of a sudden?

James Kilgore: Lots of things have happened. The first, and most important, is that people in the critically impacted communities have started to fight back. We’ve had a lot of mobilization around the War on Drugs, some of it sparked by the wonderful book by Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow. She has helped people to name what is happening.

The disenfranchisement of over six million people with felony convictions has also gained a lot of traction, especially during an election year. But people have been mobilizing in communities. The major mobilizations around police violence are also powerful indicators that things are changing. The national response around Trayvon Martin’s killing was crucial, but the organizing after the non-indictments of the killers of Michael Brown and Eric Garner has the potential to form the nucleus of a vital social justice grassroots movement with young people of color in leading roles. This could be historic but we have to see how it all plays out.

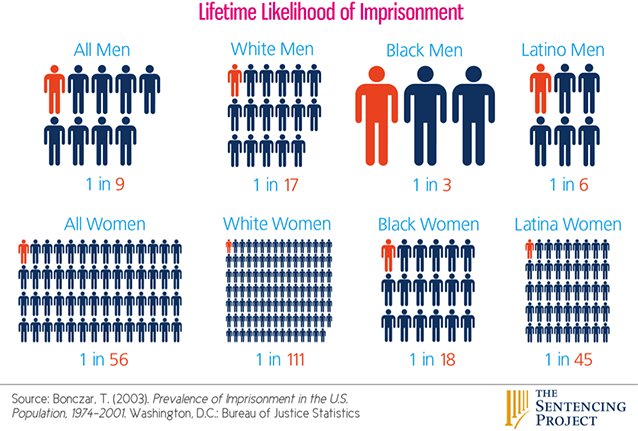

Also, the immigrant rights movement is an important complement to the largely African-American led resistance to the War on Drugs. Many people don’t connect the two, but Latinos have been the fastest growing group in the prison population in the last decade. This has largely been precipitated by anti-immigrant legislation and immigrant focused policing. So overall the mobilization of people of color has been central to putting this on the agenda.

Another critical factor is that politicians and policy makers have begun to see that too much money is going to what they call “corrections.” This isn’t just about how politically wrong it is to be locking up so many people, but also about the drain it puts on government finances. Often the fiscal arguments get intertwined with the moral and political arguments against mass incarceration. That can be a problem. But states like New York, New Jersey and Colorado are shrinking prison populations and even closing prisons. More and more politicians are seeing this, talking about it. The issue is almost becoming fashionable, in fact. That poses lots of opportunities but lots of threats as well.

ATC: You mentioned The New Jim Crow. What do you think of Michelle Alexander’s views on mass incarceration? Is her concept of the New Jim Crow a useful framework?

JK: The New Jim Crow has been a revelation to millions. No book on this topic has ever created such a buzz, both within the African-American population and among those who have never read a thing about prisons. Her notions that mass incarceration has an explicitly racist content, that the racism is no longer overtly stated (colorblindness she calls it), and that it has a political agenda to mobilize white voters to a conservative agenda are incredibly important.

She is far from the first person to make these points but she has made them most effectively. I salute her work. I have run two reading groups on this book and for almost everyone the experience has been a complete awakening about the politics of mass incarceration and race in the United States.

Having said that, there is much that the book doesn’t address what it could have. Michelle herself has recognized this as well. For instance, it focuses almost totally on how mass incarceration affects African-American men. While African-American men have been locked up at a rate that far exceeds that of any other sector of the population, mass incarceration has also had an enormous impact on their families and communities.

There is a complex gender and class dimension to this which she hasn’t captured. Women in low-income African-American communities have to pick up the pieces. They are left with financial, emotional and parenting responsibilities in the wake of the capture of millions of men from urban spaces. They also often take up the burden of supporting the men while they are in prison and after they come home and have to try to negotiate this very difficult terrain of being a job seeker and a survivor with the “felon” label.

Apart from this, Michelle also totally neglected the immigration dimension of mass incarceration which I noted earlier. Finally, I think the book could have stressed much more heavily that this is a class issue, that it is the marginalized sectors of the working class in those African-American communities who end up behind bars. Henry Louis Gates might get harassed by the police but he doesn’t end up doing 20 years for having a couple rocks in his pocket.

ATC: The labor movement has generally shied away from taking up issues related to mass incarceration, apart from prison privatization and the exploitation of cheap prison labor. Why do you think this is the case and do you see any potential for change among the trade unions on this issue?

JK: Unions for the most part have focused on the narrow employment concerns that pertain to mass incarceration. They have concentrated on blocking private prisons, which they view as undermining hard-won union gains, and protesting the use of contract prison labor. Both of these are meaningful issues, but they’re not the central working class issues of mass incarceration.

Ultimately mass incarceration is an attack on the most marginalized, most vulnerable sectors of the working-class inner-city communities of color and, in some instances, poor whites in small rural towns. These populations have been marginalized in the last three decades by deindustrialization and the rollback of union power. They are now part of that mass of workers who can be labelled precarious. They are in the low wage job market, confined to employment in places like Walmart, Target, etc. — the McJobs world. Unions have had a hard time organizing such workers, especially when they have a felony conviction.

A further complication is that many unions have lots of members who work inside prisons and jails. AFSCME for example organizes prison guards in many states. Their employment security is tied to the sustenance and growth of mass incarceration. The unions have not yet come out with a proper working-class assessment of all this. In Illinois, where I live, AFSCME has been a major force in the battle to keep prisons open when the governor wanted to close them down.

The unions should be pushing for reallocation of funding away from corrections and for re-training their members who work in prisons for employment in socially useful sectors. Let’s have them building public housing or schools in inner-city areas instead of locking up the working class. That said, a few unions like SEIU are beginning to study this issue and take some more progressive positions. The last AFL-CIO national convention passed a resolution against mass incarceration. It wasn’t as powerful as it could have been, but I think the debates around it opened up new space for contestation. Those 2.2 million people behind bars are not going away any time soon.

ATC: Hardline conservatives like Newt Gingrich and Rand Paul have recently come out against mass incarceration. We even have a rightwing grouping Right on Crime, led by Gingrich and Grover Norquist, calling for scaling back imprisonment and focusing more on re-entry and other programs. Is this a positive development? Are there hopes to form a broad coalition on this issue across the political spectrum?

JK: I am always suspicious of such coalition building, although it is totally necessary. The problem is that what might be a tactical move for a very short-term gain becomes a strategy and we end up worrying more about offending our conservative allies than mobilizing the people who are affected.

Coalition building can get some legislation passed that might get some people out of prison. For instance, California voters just passed Proposition 47, which is supposed to get some 10,000 so-called non-violent offenders (I don’t like that term) out of prison. This is a good thing, but it comes at a price. The price is that we begin to divide those who are incarcerated into the deserving and the undeserving, the people who we can live with and the people we want to throw away.

Well, more than half of the people in state prisons have convictions for so-called violent crimes. So even if we let out everyone with a conviction for a non-violent crime, we would still have an incarceration rate twice that of any European country. But more importantly, focusing on the non-violent fails to address the fundamental cause of mass incarceration. It is not about people making bad choices. It is about the political and economic forces that drove neoliberalism in the United States, shifting the role of the state to security instead of social welfare.

This is ultimately a class issue. If we make it into a question of the violent and the non-violent, we are saying that someone who is caught with drugs is somehow responding to fundamentally different forces than the person who is caught with drugs and a gun. I met hundreds of people in prison who simply got caught up in the underground economy because there was no alternative. Once you are caught up because there are no meaningful education or employment opportunities in your communities, you have to defend your territory, your life. In that world, you have to become violent to survive. The point is to restructure that world, not punish those who are swept up in the evils of an uncaring capitalist political economy that casts them onto the rubbish pile and then expects them to come out smelling like perfume.

ATC: There is also an increasing presence of formerly incarcerated people becoming active on these issues. Some organizations like All of Us or None, have called for formerly incarcerated people, particularly people of color, to step forward and lead the movement against mass incarceration. Does this seem like a viable strategy?

JK: It is vital for those who have been critically impacted to play a leading role in these movements. Those who have directly experienced a system of oppression must lead the struggle to overthrow that oppression. In this case, we must make sure it includes family and community members as well. Because about 90% of those who have been incarcerated are men doesn’t mean we will have a movement which is 90% men. That would be a disaster.

Moreover, the movement against mass incarceration must make alliances with those addressing inequality and racism in other quarters. For instance, I would love to see more linkages between those fighting for higher minimum wages and those fighting against mass incarceration. There is so much overlap. Mass incarceration touches an enormous range of the population. One in four adults now has a criminal record — they are workers, they are transgender folks, they are mentally ill, addicted. They live in communities that are impacted not only by police violence and deindustrialization but by climate change and gentrification. They live on reservations, in trailer parks, in shelters.

Unfortunately, they are everywhere and virtually all working class. This is a point so many people simply miss. Mass incarceration is a working class issue with a potential to reach into many pockets of society, catalyze lots of alliances.

ATC: Ultimately mass incarceration is a systemic problem. Some people speak of alternatives to incarceration as the solution to the problem. The more radical sectors of those involved in campaigning against mass incarceration or what some call the prison industrial complex, call for prison abolition. Where do you stand on these debates and how do they connect to developing a socialist position on these questions?

JK: I think the notion of prison abolition gets at the root causes of mass incarceration. It applies a socialist politics to issues of criminal justice. The notion of a society that doesn’t imprison people presents us with possibilities of society based on empathy and solidarity, where when someone makes a mistake our first response is to try to understand and support, rather than punish.

To get there obviously requires a major social movement with a whole new world view. That is what prison abolition proposes. In most cases, when people first encounter the idea of prison abolition, they say, “but what about Charles Manson? What about serial rapists?” While I understand the reaction, it’s simply the wrong question. A diversion. No one is advocating absolute freedom from responsibility for harmful, destructive actions. But prison abolition focuses on prioritizing and proportionality. Why do we imprison someone with a bag of dope and not even charge someone who crashes the global economy or loots workers’ pensions?

We have 2.2 million people locked up in prison. Most of these people simply don’t belong there. If we imprisoned at the rate of Norway, we would have about 200,000 people behind bars. To make serious progress toward an incarceration level of 200,000, we will need to have lots of serious discussions along the way about what a criminal justice (not injustice) system would look like. We know we are not starting down this road by calling for the release of Charles Manson. Put that aside and let’s move on.

We want the hundreds of thousands poor, marginalized workers who are locked up to be returned to their communities. We want those communities to be restored so they offer meaningful education and employment opportunities. We want adequate public housing. That’s what prison abolition is about, not freeing the most destructive individuals our society has produced.

Having said that, at times, advocates of prison abolition, like virtually everyone on the Left, have engaged in sectarian politics, have spent more time attacking those who opposed abolition than focusing on the perpetrators of mass incarceration. We need to work harder at shaping what prison abolition means and how it might be relevant for people. At the same time, along the way we have to fight for reforms, changes that impact people’s lives — without becoming totally immersed in the day to day and losing the vision of a different type of society. But that’s what effective socialists have always done, lead the struggle for reform while keeping their eyes on the prize.

James Kilgore is a longtime activist, writer, and researcher. He currently lives in Urbana, Illinois, where has been involved in local movements to pass a Ban the Box initiative (taking questions about criminal background off employment applications) and opposing the building of a new county jail. He spent six and a half years in prison (2002-09) for his participation in political violence in the 1970s. He has published three novels, all of which were drafted while he was incarcerated. His next book is A People’s Guide to Mass Incarceration, to be published by The New Press in 2015.

In the course of the past year, James has been involved in a struggle to maintain his job as a contract lecturer and hourly employee at the University of Illinois. In early 2014 the ultra-conservative local newspaper published a sensationalist major feature article about his past and demanded that his actions and criminal convictions mandated his dismissal from the University. At first the University authorities gave in and refused to renew his contract. But after a petition of over 300 faculty members demanded his reinstatement and a university-appointed faculty committee also recommended he be re-hired, the Administration changed its mind. He is now slated to work at the university again in the spring of 2015.

His review of three books about prison, including Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (ATC 153) is available online. He was interviewed by Dianne Feeley from the ATC editorial board.