A. Smith

May 26, 2018

Left-wing analyses of capitalist ideology insightfully expose how personal responsibility is deployed to blame marginalized populations for what are actually consequences of oppression. The implications of this critique for body odor medical conditions, however, are rarely spelled out.

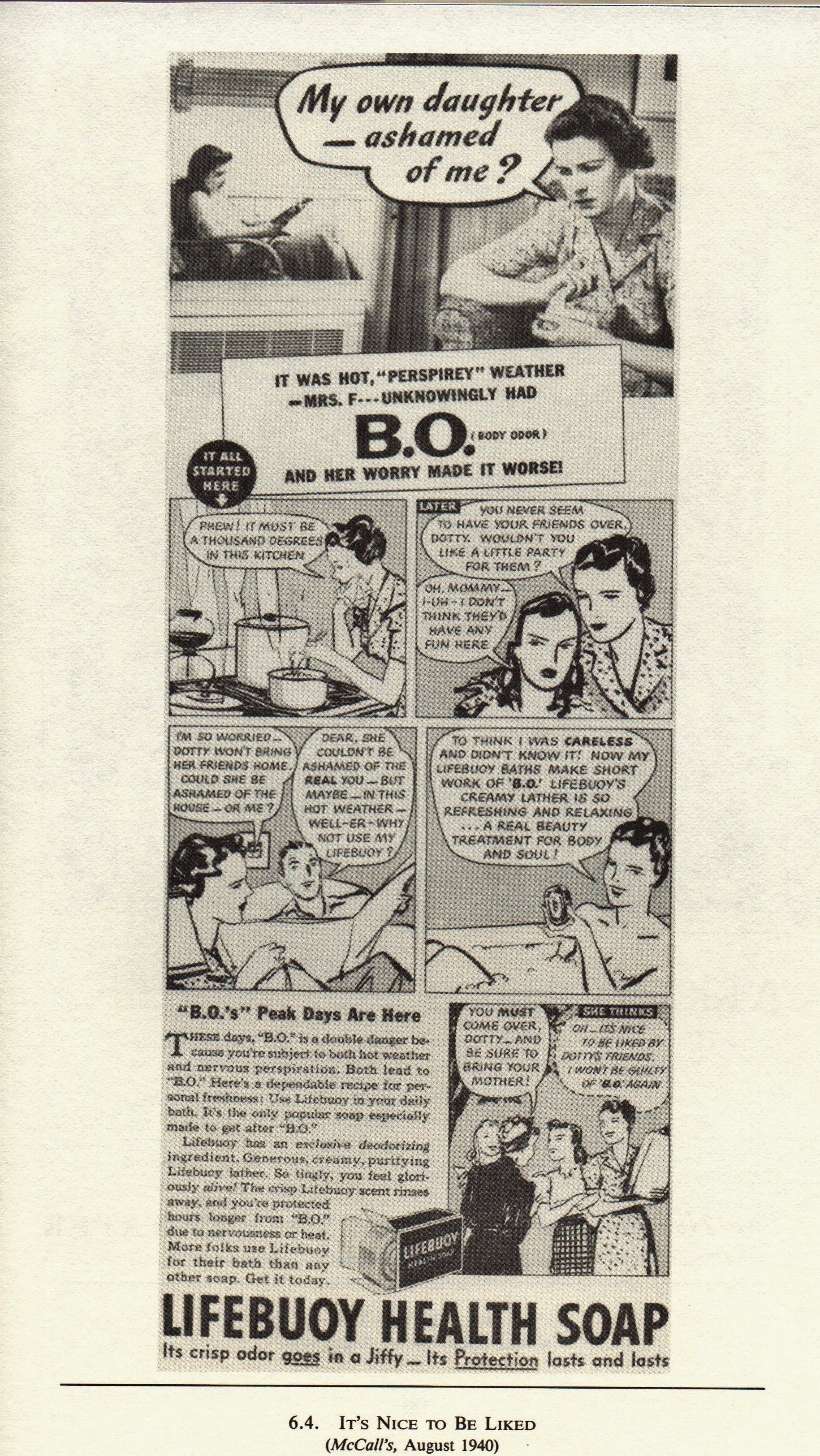

Since the early twentieth century, corporate advertising has invoked norms of personal responsibility and body shaming to disseminate the myth that all people have the ability and obligation to become odorless through consumption of hygiene commodities. The billions of dollars invested in ads for soap, deodorant and mouthwash have effectively erased those who do not have full control over the way they smell due to metabolic conditions like Trimethylaminuria (TMAU), certain digestive disorders, or other medical reasons. A USDA publication has estimated that “as much as one percent of the U.S. population may suffer from a genetic defect … leading to development of a fishy body odor” characteristic of TMAU.

Discrimination against persons with body odor medical conditions — especially in the workplace — deserves attention from the Left because it sheds light on corporeal disciplinary techniques used by employers and often tolerated by able-bodied employees, and exposes the resilience of ableist, racist and sexist body-shaming traditions.

Capitalism and Body Odor Discrimination

As Stuart Ewen’s 1977 study of advertising showed, the harm wrought by ads for hygiene products extended well beyond their efforts to make individual self-esteem dependent on commodity consumption.

Ads also helped naturalize workplace insecurity, making it go without question that bosses had the right to fire employees for minor bodily transgressions, and that workers’ only protection against this arbitrary power was to exercise self-critical vigilance against their own bodies.1

In today’s workplace, despite neoliberalism’s feigned devotion to freedom and diversity, employees are still under constant pressure to discipline and “improve” their bodies.2 The dictatorial power over employees which Elizabeth Anderson recently identified in US workplaces is often manifested as physical control. Companies which consider restroom use to be “time theft” can make employees resort to diapers. The “offense” of menstruating recently got a worker fired. Even elite employees in tech companies reportedly experience pressure to use anti-aging treatments.

Responses to reports of workplace oppression like the above vary from concern to outrage. The public rarely learns, however, of bullying and firing experienced regularly by workers with strongly scented bodies. Indeed, work-related factors undoubtedly contributed to the emergence and increasing influence of the modern norm of odorlessness. These factors include demanding that workers present themselves “professionally,” as well as the growing use of spatial arrangements like cubicle-based offices. Ads for hygiene products also frequently reinforce this pressure by warning consumers not to offend colleagues by the way they smell.

Workplace harassment and unemployment are constant topics on TMAU forums, yet these remain voices in the wilderness. The demonization of body odor through corporate ads and entertainment shows has succeeded in dictating the way body odor is interpreted and disciplined. This hegemony forces a tiny number of activists — advocacy groups like MEBO and a few brave individuals on blogs or YouTube — to battle stigma unsupported by better-established disability rights groups or left-wing parties.

Medicine, Law, and the “Normal” Body

To date, prejudice against body odor has proven far more unassailable than many other oppressive body norms (sizeism, ageism, cis-normativity and others). Systematic discrimination leads many strong-smelling individuals to advocate for medical research into the causes of their difference, so as to counter the prejudice that body odor is always a sign of poor hygiene. Self-medicalization and pathologization have the troubling implication of reinforcing the myth that the “normal,” healthy body is odorless, rather than insisting on recognition that bodies vary naturally in scent. However, the medical approach is currently the only (limited) protection for strong-smelling persons against discrimination in the workplace, public transportation and elsewhere. Growing acknowledgement that many disabilities are socially constructed should expose the socioeconomic forces which have led natural variation in odor to be interpreted solely through the restrictive binary of dirtiness or illness.

While awareness-raising campaigns have succeeded in getting certain types of body odor condition protected through the Americans with Disabilities Act, it is still lawful for employers to segregate such workers from coworkers and from the public.

Kelly Fidoe-White, who has TMAU, with her husband Michael. Photo: Barcroft Media

Kelly Fidoe-White, who has TMAU, with her husband Michael. Photo: Barcroft MediaAccording to the Job Accommodation Network, a service of the US Department of Labor responsible for interpreting the Americans with Disabilities Act, employers have the right to require a worker with a body odor related disability to use “a private office with an air-purification system,” to “work from home,” or work in “a position that does not involve direct contact with the public.” Invoking the ADA so as to condone spatial exclusion is only one of numerous instances of officially sanctioned discrimination against people with body odor, which include many public libraries banning strongly smelling visitors, a city in Washington outlawing “Bodily hygiene or scent that is unreasonably offensive to others” in public spaces in 2014, or the TSA listing “strong body odor” among its criteria for suspected terrorists in 2015. Policies of spatial exclusion conceal the fact that employees may be accepting of a coworker with a body odor related disability if they are educated about the condition, as exemplified by the experience of Kelly Fidoe-White, a British radiographer who has TMAU.

Leftist Writers: An Ambivalent Heritage

It is unclear whether the Left remains silent due to lack of awareness about ongoing discrimination or due to conscious idealization of the sanitized, controlled, odorless body. Many left-wing writers continue to celebrate figures like George Orwell, who simplistically associated body odor with the working class in The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) and condoned hatred of strong-smelling individuals:

“Race-hatred, religious hatred, differences of education, of temperament, of intellect, even differences of moral code, can be got over; but physical repulsion can-not. You can have an affection for a murderer or a sodomite, but you cannot have an affection for a man whose breath stinks–habitually stinks, I mean. However well you may wish him, however much you may admire his mind and character, if his breath stinks he is horrible and in your heart of hearts you will hate him”.3

The norm of odorlessness was a relatively recent imposition when Orwell voiced this view — Alain Corbin’s study of urban hygienic projects dates it to the nineteenth century and connects its appeal to bourgeois efforts to self-differentiate from lower classes through bodily and spatial practices.4 Instead of exposing class-based bias against workers’ bodies, Orwell uncritically replicated it.

However, the left-wing tradition also includes significant counter-voices. Herbert Marcuse admired “the body unsoiled by plastic cleanliness.” Distinguishing the new sensibility of “men and women who do not have to be ashamed of themselves anymore because they have overcome their sense of guilt” from “the false fathers who have built and tolerated and forgotten the Auschwitzs and Vietnams of history,” he satirized the “daily bath or shower for people whose cleaning practices involve systematic torture, slaughtering, poisoning”.5 These were not casual comments: historically shifting attitudes toward olfaction received prominence in Eros and Civilization, where “Marcuse envisages a civilization that will be less coercive thanks to the abolition of conscious repression. Denying this additional sublimation of the sense of smell can thus play a role in man’s liberation”.6 Similarly, Paolo Freire pointed out that people who consider themselves purer than the “great unwashed” cannot engage in dialogue.7

Writers in the fields of eco-socialism, eco-psychology and eco-feminism have criticized ways that modern economic ideology and advertising construe people as having infinite bodily needs which they must meet through consumption of commodities: William Leiss, Andy Fisher and Richard Twine specifically criticize the hygiene industry.8 Of course, body odor disabilities like TMAU have nothing to do with poor hygiene, but as long as the norm of the puritanically odorless body reigns unchallenged, people with such conditions will continue to be stigmatized.

Racism, Hygiene, and Stigma

Academic research lends support to Marcuse’s insight that preoccupation with cleanliness is frequently deployed to lend respectability to oppressive projects.

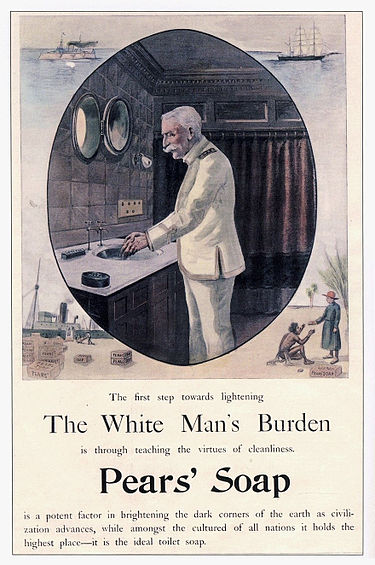

Differentiating between supposedly clean and dirty bodies served ideologically to construe imperialism as a civilizing mission, displace Euro-American white working-class consciousness into feelings of racial superiority, and regulate laborers’ bodies, while bringing in profit for soap companies.

Anne McClintock,Timothy Burke and others studied classist and imperialist themes in nineteenth-century hygiene campaigns, showing that soap companies and missionaries relied on racist stereotypes to impose Western hygiene practices in British colonies.9

Carl Zimring’s recent Clean and White shows how non-whites in the US were associated with dirtiness and relegated to work in waste-related urban occupations starting in the nineteenth century; such racist stereotyping led to toxic waste being dumped predominantly near black communities.10

Awareness about the links between hygiene and racist constructions is not restricted to academic circles: recent controversy over an ad for Dove soap which appeared to feature a dark-skinned woman becoming white after using the product revealed that many commenters know that soap companies’ use of such racist tropes go back to the nineteenth century.

However, simply acknowledging that dark-skinned people have been depicted as dirty does not raise more fundamental questions about the politics of hygiene and odorlessness. Some of the academic texts, as well as most of the public discussion about the soap ad, maintain that the modern Western obsession with cleanliness is a manifestation of progress and civilization, and its racist applications an unfortunate accident. They do not ask us to rethink hatred toward strong-smelling people, only racist assumptions about who can be expected to be strong-smelling. As one of the journalists responding to the Dove ad commented:

“What do these tone-deaf advertising campaigns have to do with soap, arguably the world’s most innocuous object adored by 99 percent of human beings? I wish I could tell you. But If I could say anything to these soap brands, it’d be this: Body odor does not discriminate, and neither should you.”

They replace racist generalization with meritocratic individual responsibility: it is no longer acceptable to assume that dark-skinned people are dirty, but it is fair to exclude strong-smelling persons as individuals, regardless of their color. Like so many other instances of meritocracy, this norm is ableist: it erases the reality that the bodies of people with disabilities like TMAU cannot become odorless, as well as the fact that this has nothing to do with poor hygiene.

The Politics of Odorlessness

Approaches which distinguish hygiene obsession from racism fail to interrogate the deeper reasons for our culture’s need to control and purify the body. As philosopher Dana Berthold noted, “Even those of us who readily admit a strong historical link between hygiene and racism find ourselves resistant to the idea that our own preoccupation with hygiene has some racist roots.”11 Yet today hygiene is

“a conception linked to white privilege in our particular time. On one level, this is a self that is alienated from the physical world and therefore aims to subdue the indicators of its own physical embodiment. In this regard, the self is anxious about bodily boundaries because it defines itself through what it excludes or washes away. On another level, cleanliness is more abstract and has to do with belief in one group’s moral superiority over another group considered less civilized and “closer to nature.” On both levels, the alienated other is what makes this self a self.”12

A relatively recent imposition, the requirement that all bodies be totally odorless is an essentially oppressive project. Odorlessness, cleanliness and disgust are not neutral categories today, but continue to be loaded with exclusionary purposes: Martha Nussbaum has explored how “the discomfort people feel over the fact of having an animal body is projected outwards onto vulnerable people and groups.”13 Citing contemporary and historical examples from a range of cultures, anthropologist Constance Classen found that, “[i]t is common… for the dominant class in a society to characterize itself as pleasant-smelling, or inodorate, and the subordinate class as foul-smelling.”14 In her examples, subordinate groups are rhetorically assigned an olfactory stigma to warn of the disorder that would ensue if they step beyond the bounds of their allotted inferior status.

This pattern explains, for instance, why a group of female peace activists studied by Tim Cresswell were systematically represented by opponents as dirty and bad-smelling, even though these accusations seemed unfounded to independent observers. The charges of bad hygiene had less to do with the activists’ actual smell than with reactionary fears about women in radical political roles.15 Recent psychological studies on disgust, likewise, conclude that individuals who are preoccupied with cleanliness and easily disgusted are often politically authoritarian.16 Commentators have cited this research to make sense of Donald Trump’s frequent body-shaming outbursts.

Left-wing movements, especially ones committed to inclusion of people with disabilities, owe solidarity to all groups relegated by capitalism to what Zygmunt Bauman described as the category of “wasted lives.”17 The Left should militantly contest employers’ control over all workers’ bodies, protest the exclusion of all individuals with non-conforming bodies from public spaces, and oppose all body shaming — including corporations’ demonization of strong-smelling people for the purpose of marketing hygiene commodities.

A. Smith is an independent researcher who writes about people with nonconforming bodies in the context of advanced capitalism; their interests include the intersections between anti-ableist, queer, environmentalist and anti-capitalist activism.

1. Stuart Ewen, Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of Consumer Culture (1977), 37, 46.↩

2. Philip Mirowski, Never Let A Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown (2013), 113. ↩

3. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937).↩

4. Alain Corbin, The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination, trans. Miriam L. Kochan (Cambridge, Mass., 1986).↩

5. Herbert Marcuse, An Essay On Liberation (1969), 24, 28, 36.↩

6. Annick Le Guérer, Scent: The Mysterious and Essential Powers of Smell, trans. Richard Miller (1992), 193.↩

7. Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), 78.↩

8. William Leiss, The Limits to Satisfaction: An Essay on the Problem of Needs and Commodities (1976), 18; Andy Fisher, Radical Ecopsychology (2002), 166-8; Richard T. Twine, “Ma(r)king Essence-Ecofeminism and Embodiment” Ethics and the Environment 6: 2 (2001), 46-7.↩

9. Warwick Anderson, 1995. “Excremental Colonialism: Public Health and the Poetics of Pollution” Critical Inquiry 21: 3 (1995), 640-69; Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest (1995); Timothy Burke, Lifebuoy Men, Lux Women: Commodification, Consumption, and Cleanliness in Modern Zimbabwe (1996); Brian Lewis, ‘So Clean’: Lord Leverhulme, Soap and Civilization(2008). ↩

10. Carl A. Zimring, ‘Clean and White’: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States (2017).↩

11. Dana Berthold, “Tidy Whiteness: A Genealogy of Race, Purity, and Hygiene,” Ethics & The Environment 15 (1) 2010, 3.↩

12. Ibid, 14. ↩

13. Martha C. Nussbaum, Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law (2004), 74.↩

14. Constance Classen, “The Odor of the Other: Olfactory Symbolism and Cultural Categories.” Ethos 20: 2 (1992), 136.↩

15. Tim Cresswell, In Place/Out of Place: Geography, Ideology, and Transgression (1996), Chapter 5.↩

16. Gordon Hodson and Kimberly Costello, “Interpersonal Disgust, Ideological Orientations, and Dehumanization as Predictors of Intergroup Attitudes. Psychological Science 18: 8 (2007), 691-98; Eric G. Helzer and David A. Pizarro, “Dirty Liberals! Reminders of Physical Cleanliness Influence Moral and Political Attitudes” Psychological Science 22 :4 (2011), 517-22; Marco Tullio Liuzza, Torun Lindholm, et al., “Body odour disgust sensitivity predicts authoritarian attitudes,” Royal Society Open Science (February 28, 2018).↩

17. Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts (2004).↩

Comments

2 responses to “Left-wing Solidarity with Disability Activism and the Taboo of Body Odor Medical Conditions”

Also, having faced discrimination at work( losing work, without the mention of my not-understood condition), based on TMAU, and given the degree of ignorance around it (eg doctors, dentists, educationalists)the question of educating the populace seems of paramount importance if we are to be treated fairly and with compassion.

Thanks for your erudition! I still admire Orwell, a lot. His ignorance of TMAU, for example, is not a heinous crime. I developed TMAU at 22-ish and did not know it had a name until I was in my forties. I enjoyed reading this and would like to read more of your work if you could direct me to it? Thanks.