by Robert Bartlett

June 18, 2013

The success of the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) strike in September 2012 was a stunning rebuke to the forces of privatization and corporate education reform. The defeat of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s ambitions to deal a decisive blow against the largest union in Chicago took on national implications precisely due to continued implementation of the school reform model of closing public schools and replacing them with publicly funded but privately run charter schools. Chicago teachers and a majority of the parents of Chicago students fought back against the national basis of this campaign, fronted by Arne Duncan, the former CEO of the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) and Obama’s current Secretary of Education, through national programs like Race to the Top.

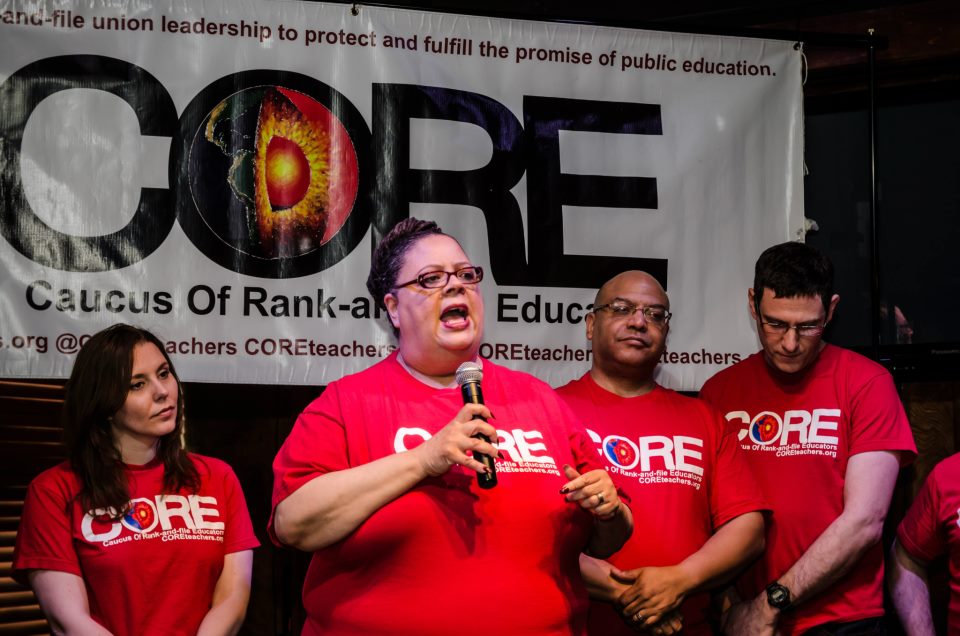

Three years ago when the Caucus of Rank and File Educators (CORE) ran for leadership of the CTU, few would have predicted their ability to turn the union around from six years of do-little leadership into a force capable of taking on a nationally funded, bipartisan “education reform” movement that seemed likely to achieve its goal of weakening and possibly destroying the largest remaining union sector in the United States—public education unions. CORE and the CTU’s success was not due to replacing a weak leadership with a militant one willing to strike, but rather to the creation of a layer of union members in the CTU who saw the struggle as one for what CTU president Karen Lewis calls “the soul of public education.”

I would like to trace the evolution of CORE as a coherent and fundamentally different union leadership that transcended traditional trade-union politics and became the inspiration for a new vision of social unionism. This new model is needed if the union movement is to survive the corporate onslaught, much less expand to champion the needs of the increasingly impoverished working class. Secondly, the articulation of a new type of unionism capable of both mobilizing teachers and reaching out to a community that is underserved by underfunded schools had to be carried out both within the CTU and in the community of parents and students who make up public education in Chicago. There were significant barriers to achieving this melding of trade union demands and the needs of Chicago’s students that had to be overcome during the course of organizing for the strike. A key part of how this was accomplished was by building alliances between the union and the community that involved developing a shared vision of what education should be, and pointing out where it falls short.

Photo: Sarah Jane Rhee

Building CORE out of the Failure of Traditional Union Reform

CORE might not have come into existence, much less risen to lead the third-largest teachers’ union local in the United States, if it were not for the failure of a previous reform group in the CTU, the Pro-Active Chicago Teachers (PACT). PACT in 2001 had ousted the local chapter of the national caucus that controls the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the Progressive Caucus, then led by Sandra Feldman, now led by Randi Weingarten. The United Progressive Caucus (UPC) had an uninterrupted leadership of the Chicago local since the 1960s and was known as the group which had led the CTU in a series of eight strikes, including the last previous strike in 1987. After it, relations between the union and the city became routine, and the UPC settled into a complacency in the face of a steady erosion of teacher rights, exemplified by the 1995 state legislation that eliminated system-wide seniority and limited the ability of the CTU (but not other teachers’ unions in Illinois) to bargain over issues other than wages and benefits. Specifically excluded from the scope of bargaining were matters like class size, staffing, contracting out, and other areas that affect both working conditions and pedagogy.

PACT was founded by Debbie Lynch, who had previously worked in the national AFT, but had left that job to return to Chicago and go back into the classroom. There had been previous opposition candidates to the UPC, coming out of caucuses built around the newspaper Substance, that had received as much as 30 percent of the vote, but whose support was concentrated in the high schools, which tend to be more militant, and the votes for whom were primarily protest votes. PACT capitalized on the weak UPC leadership of Tom Reese, who succeeded the more militant Jacqueline Vaughn after her death. Reese’s lack of charisma and the lackluster leadership of the union in the beginning phases of the corporate agenda led to an opening that the dynamic and articulate Debbie Lynch was able to use to propel her caucus to leadership in the CTU in 2001. The next three years saw some modest improvements in how the union was run, but PACT leadership got bogged down into a consuming factional warfare. But for a bungled attempt to sell a new contract that was initially voted down by members unhappy with the modest wage increases and higher health care premiums, the Lynch leadership might have won reelection, but instead it was narrowly defeated by the UPC in 2004.

The PACT experience was one that a number of the activists who formed CORE went through, and it provided a bitter lesson in the limitations of traditional union reform. One lesson was the severe constraints of the traditional top-down leadership model that Debbie Lynch and most union reformers follow, and the inability to transform PACT into a broad-based caucus that was independent of Lynch. Because those in PACT’s leadership layer who went into the union staff were consumed by the challenges of running the union, the caucus languished and was unable to grow significantly. The radical caucus had a rather traditional role of supporting the elected leaders of their own radical caucus and did not play a role in developing rank-and-file members as leaders who had some responsibility in debating issues and making decisions as to what the policy of the caucus would be—a problem for all insurgent groupings.

A second expression of reform from above was a rhetorical opposition to some of the changes that had been imposed on the CTU, through a strategy of playing an inside game of attempting to lobby for changes, rather than mobilizing the membership. Negotiation of the contract was kept within a small group, and no one outside of the negotiating team knew what was being fought for. When Lynch came out with an agreement that had modest wage gains plus increases in health care premiums, those issues seemed more important to members than broadening the scope of permissive bargaining, which was limited by state laws. A clause in the contract that forced the Board to eliminate a non-tenured category in which teachers were kept indefinitely was an improvement, but the overselling of the contract, as the best that could be gained, allowed the UPC to campaign against it and led to its rejection. The contract fiasco led in large part to the PACT defeat.

A layer of CTU activists had finally changed what they viewed as a corrupt and weak UPC leadership, only to find that the impulse of the “reform from above” movement had been stymied by conservative forces within the union and the lack of a real ability to involve the members in changing the course of the union. People who later played key roles in the formation of CORE left PACT at this time in response to its limitations, and its overwhelming defeat in the subsequent 2007 union elections further disillusioned these activists who saw that PACT had become tainted through its missteps and its inability to transcend the domination of Debbie Lynch. The ground was ripe for a new type of union reform.

The Genesis of CORE

During the six years of UPC rule from 2004 to 2010, the corporate reform agenda began to take hold and gather steam. Corporate groups proposed a plan in 2004 to restructure Chicago schools that was adopted by Mayor Richard M. Daley and became known as Renaissance 2010. It proposed to close low-performing schools and replace them with a mixture of publicly funded and privately run charter schools and a process of “turnaround” schools where the entire staff—from principals through lunch ladies—lose their jobs and are replaced with an entirely new staff. This new staff was often predominantly white and young, with little or no teaching experience. This program was led by CEO Arne Duncan, who himself had no teaching experience, and who was appointed by a school board handpicked by the mayor without any democratic public input.

Under Renaissance 2010 the sector of privately run charters expanded, which siphoned off students from the neighborhood schools, reaching about 10 percent of the CPS student population by 2010. Teachers in some of the most impoverished neighborhoods in Chicago, with predominantly African-American staffs, began to lose their jobs as their schools were either closed or “turned around.” Jackson Potter, the person most responsible for starting CORE, related the response of the UPC to this burgeoning crisis: in a meeting of the soon to be fired staff at his school, the UPC union leader told the members to “start polishing up their resumes.” That was when he said that he knew another caucus had to be formed. Shortly thereafter, in 2008, he invited a small group of teachers he knew to a meeting to start what became CORE.

One of the early CORE activities that influenced the future direction of the caucus was the visit of British Columbia Teachers Federation (BCTF) leader Jinny Sims to speak at a forum. Her talk about how the BCTF organized province-wide to bring their issues to the public and involve their entire membership in a contract campaign that culminated in an illegal strike, and their work against standardized-testing encroachment provided a concrete model from which CORE could learn. The BCTF program of member education and involvement in the process of educating the public over their issues in a conservative province was influential in shaping the future activities of CORE. The initial group ranged from teachers in their twenties to people in their fifties, including socially conscious teachers attracted to groups like Teachers for Social Justice; former PACT members; and members of socialist groups like the International Socialist Organization, Solidarity, and the Progressive Labor Party, as well as unaffiliated radicals. This group discussed the global nature of the changes that were threatening public education and began to form a coherent vision of the scope and nature of these threats and to talk about what was needed effectively to counter this new manifestation of global capitalism. A shared vision of the source of the problem or the weaknesses of the current union leadership was not a program or a plan, however. That remained to be developed through a series of shared experiences confronting the forces of school reform.

People who wanted to fight back against the encroaching privatization began to be attracted to CORE, which started a series of audacious actions against school closings. When a school was targeted for closing or turnaround, CORE members went to the school and met the teachers and parents who wanted to fight the closings and did whatever they could to help build a resistance in that community. This ranged from leafleting at the school to camping out overnight in front of the Board of Education in January or in front of schools with parents. Kristine Mayle, who later became the financial secretary of the CTU, met and joined CORE when they visited her school after it was put on the list to be closed.

Most teachers threatened with losing their jobs do not automatically respond by trying to fight back, but a critical layer started going to school board meetings, bringing with them parents and teachers from the affected schools, as well as community organizations that were also opposed to board policies, to testify at board meetings and become a public opposition to privatization. This involved a considerable commitment of time, since any members of the public who wanted to testify at the school board meeting (which was held during school hours) had to arrive at the board headquarters by 6 AM to be in line to sign up for their two minutes in front of the board.

This increasingly public activity was very different from traditional union oppositions, which often limit their activities to internally voiced critiques of the current leadership. In addition to bringing the issue of school closings up in monthly CTU House of Delegates meetings, CORE began to function as a dual leadership within the union. The inability of the faction-ridden UPC leadership to propose effective action opened the door for CORE to begin to mobilize other CTU members and, most importantly, to begin to forge links to community organizations that were also opposed to the shuttering of schools in their neighborhoods. In the mid–2000s, years before CORE formed, some of its leaders had developed links with community groups who were fighting gentrification and the destruction of schools in response to Chicago’s Plan for Transformation in Chicago’s Mid-South area. Groups like the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization (KOCO) and Action Now began collaborating with CORE and formed the basis of the broadening of ties to other community organizations. This period of organization and actions against the board policies attracted more people to CORE, as the UPC leadership continued to abstain from any consistent resistance to the privatization movement and refused to try mobilizing the membership.

This growth would most likely have continued, but an internal crisis within the UPC that led to the expulsion of union Vice President Ted Dallas over charges of financial improprieties forced CORE to consider running for office. By the time of the union election in 2010, five groups were contending in the campaign, and no group won a majority in the first round. Interestingly, the campaign itself provided an opportunity to widen the mobilization of the union. When the UPC adopted a CORE proposal to hold a rally of union members in downtown Chicago, weeks before the election, it became a spirited and militant march of several thousand members to the Board of Education headquarters. Flatfooted and slow to respond to the changed climate in Chicago, the UPC lost to an increasingly confident CORE by a 60 percent to 40 percent vote in a runoff. However, despite CORE’s vision and growing involvement in activities to defend public education, its victory was due more to the memberships’ willingness to try a new path to confront the attacks on them and the demonstrated lack of capacity of the previous leadership to effectively oppose the corporate led attack.

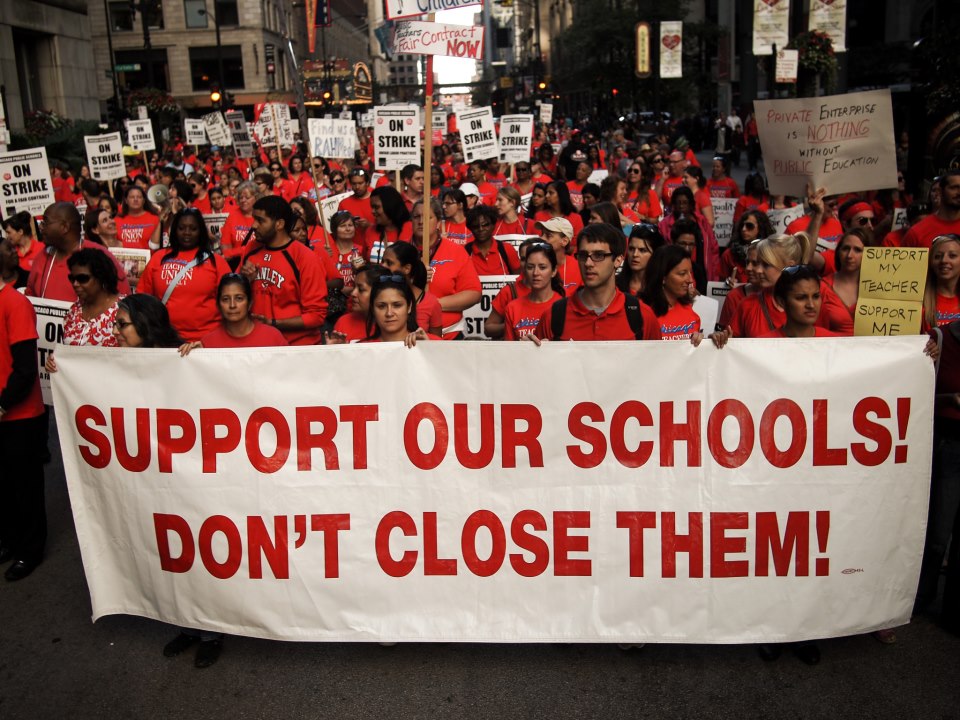

Photo: Sarah Jane Rhee

CORE came into office with a dedicated and talented group of members and officers, but these lacked experience in running a union, which led one television commentator, Walter Jacobsen, to opine that the city leaders were waiting to “feast on the rookies.” Despite their lack of experience in running a union, one key difference in the group of people now elected to office was that, instead of having a caucus built around a dominant personality, there was a group of people who had worked together to form the caucus and develop its program. This group was not focused on the struggle to gain power within the union, but to oppose the attacks on public education and the union. Jackson Potter, on the evening when the election votes were counted and it was clear that CORE had won, memorably stated that they would have to go on strike when the current contract expired—a daunting challenge in a union that had not struck in over twenty years.

The course of the last ten years of attacks on teachers and education had led to the growth of a talented and farsighted team of people leading the radical caucus and now the union. This leadership was forged through their history of open meetings, spirited debate and discussion over their plans, and was selected on the basis of both their participation in previous actions and their articulation of a program of involving the members and the community they serve in a common struggle. One symbolic representation of this was that radical caucus members would stand behind and together with their representatives in the early days of going to testify at board meanings—in order to provide a show of unity. Now the challenge of running a union determined to fight the attacks on public education began.

Changing the Culture of the Union

One important symbolic change that was instituted was a reduction in the salaries of teachers who took union jobs. Traditionally, union officers and staffers were paid salaries that were far more than that of a classroom teacher. Under CORE, staff salaries would be tied to the lane and step system of classroom teachers, and they would be paid based upon the twelve-month calendar of the union contract. This freed up a significant amount of money that could be used to hire more staff to further the organizing plans of the new leadership, and sent a signal to the membership that it was not going to be business as usual.

One of the first tasks was to change the union from a service model. The main task of the leadership and office staff in this model is to process grievances, defend the contract, and represent the membership. CORE had a different model in mind when they decided to put forward an “organizing model.” It was beyond the ability of a small staff to take on the national forces that were propelling the growth of charters, led by hedge-fund billionaires, groups like the Gates and Walton Foundations, and supported by an aggressive push on the part of the Obama administration through programs like Race to the Top. A mass movement was needed to stand up to this attack. The union membership had to be fully involved in all aspects of the unfolding campaign, and able to articulate the vision of a quality education to parents and community members. It could not just respond to calls to attend a demonstration if a successful contract were to be negotiated.

Structural changes in the CTU included the creation of an organizing department that was responsible for internal organization of the membership and developing ties to the community organizations and parents who were the natural allies of teachers. The shift of resources from the grievance department to organizers who spent more of their time in the schools and community than in the office was no symbolic move; it was integral to the fight that loomed in two years when the contract expired. With 600 schools spread across the city, the small grievance department was stretched to be able to adequately cover them all.

The early days of running the union brought immediate challenges, as the Board of Education tested the union by demanding that they forego a contracted pay raise or face layoffs of members. CTU refused, and the board responded by firing 1,500 teachers. While this was challenged legally, it was also used as an opportunity to continue the mobilization that had marked the end of the election campaign. As the union responded to school closings and the firings of members, it faced a relentless propaganda campaign designed to paint teachers as the villains, legislation designed to both weaken the union and make it impossible to strike, and the election of an aggressive new mayor. It also began to form a plan to prepare for the contract expiration in two years. Along with waging defensive struggles, the new leadership had to prepare the membership for the likelihood of a strike. This involved internal organizing, broadening ties with community and other groups, and beginning to take on the forces that were leading privatization and denying the schools needed resources through, among other things, projecting an alternative vision of what education should be for Chicago’s children.

The internal organizing had a goal of setting up action committees in every school, with committee members responsible for staying in touch with around ten other employees each; these were not just teachers but also members of other unions. Internal trainings of union delegates helped them to become more effective through workshops on contract enforcement. Assessments of the weaknesses in buildings (i.e., individual schools) gave a sense of how prepared the membership was to strike. Regional meetings were held, open to all members, to listen to the union message and express opinions. Organized phone-banking was used to talk to targeted groups within the union—describing actions taken by the board, projecting a vision of how the union could organize to win, and determining the strike readiness of the membership.

Comments

2 responses to “Creating a New Model of Social Union: CORE and the Chicago Teachers Union”

Closing down a school is not a solution. I got angry when I read it. The giant gathering proves how much they are concerned.

on line gambling site in Australia. The on-line betting internet site for foreign gamers that have slot machines, live roulette and video on-line poker, highly recommended.