by Dianne Feeley

December 16, 2015

The 2015 UAW/Big Three contracts took 67 days and multiple attempts to ratify, resulting in what most autoworkers see as a partial victory.

After confidently strutting during last summer’s bargaining convention, the UAW leadership never attempted to organize workers for a contract campaign. Having suspended their right to strike at the time of the 2008-09 financial crisis, GM and Chrysler/Fiat (FCA) workers were able to rejoin Ford workers this time around in being able to utilize their strike weapon. But if the convention was drowned in “It’s Our Turn” and “Bridge the Gap” slogans, membership preparation didn’t go beyond taking formal strike votes. My local printed a “No two tier” T-shirt for us to wear at the Detroit Labor Day Parade but elsewhere union activists designed, distributed, and wore “No two tiers” shirts all on their own.

While labor costs differ for the Big Three, the Center for Automotive Research pegs them in the range of 4-8%. Costs went down with the introduction of second-tier workers, who were hired at half rate, with less comprehensive health care coverage and a measly 401(k) instead of a defined pension. It was somewhat surprising, then, that despite Chrysler being the smallest of the Big Three, and where fully 45% of the work force is second tier, UAW President Dennis Williams chose it as the negotiating target. Traditionally the first corporation chosen is the strongest, with the contract setting the pattern for the others. This time around Williams chose the weakest.

Rejecting the Marchionne “Solution”

CEO Sergio Marchionne, whose salary and benefits totaled $72 million last year, had been vocal in seeing two-tier wages as a problem–“almost offensive.” His solution: Eliminate the top tier! Unveiling a five-year product plan in the spring of 2014, he commented:

“I always have been of the view that the two-tier wage structures are unsustainable in the long term….The real problem here is we need to freeze the tier ones and make them a dying class. I don’t mean this literally.

“We have to replace the tier two-wage structure with something that reflects the sharing of the economics of running this enterprise. I do see in some particular cases the tier twos should be able to make more than a tier one, but only in the event that the company is successful. I object violently to the notion of entitlement in the wage structure. That is something that is incredibly unwise.”

Sergio Marchionne (left) and UAW President Dennis Williams, during a ceremony that opened contract negotiations.

When the tentative agreement was approved by a majority of the UAW bargaining committee, Chrysler workers were outraged to learn that the proposal was to follow Marchionne’s lead, gradually increasing the second-tier wage, currently between $15.78-19.28 an hour, to a high of $25. This still left a wage gap between the second-tier and those hired before 2007. As the veteran workers retired, so would their wage scale. The contract was “a bridge to nowhere.”

An additional slap in the face was the disappearance of the 25% maximum on the number of lower-tier workers that was to take effect at the expiration of the 2011 agreement. Many senior second-tier workers had held onto their jobs in anticipation of moving to the higher wage with the new contract. When UAW Chrysler Vice President Norwood Jewell said that commitment was never guaranteed, workers pointed to wording in the union’s own contract summary. The lie was infuriating.

Over the last couple of decades the strategy employed to get UAW contracts passed has been to offer particularly large signing bonuses. The Chrysler agreement offered a $3,000 bonus to veteran workers and $2,000 to the second tier. With that carrot, autoworkers were supposed to overlook the continued stress of the work schedule. Workers are told that it’s unrealistic to expect to win back in one contract what was lost in the economic crisis. The Cost-of-Living-Adjustment that autoworkers first won in the aftermath of World War II is no longer possible. One just has to get used to “the new normal.”

First-tier workers, stuck at $28 an hour for the last decade, were slated to receive two 3% wage increases and two 4% lump-sum bonuses. Having already lost $4 an hour since COLA was suspended in 2009, these workers would find real wages further deteriorated four years down the road.

Chrysler has adopted an onerous Alternative Work Schedule at most of its plants. This condemns the work force to odd schedules and cheats them out of overtime pay first won at Chrysler in 1937!

A draconian absentee policy and continued skilled trades consolidation remained in place. The agreement also proposed shifting health care to an unexplained heath care co-op.

Chrysler promised a $5.3 million investment, but this would result in few additional jobs. The corporation also announced it would like to move all small car production to Mexico; only SUVs and trucks would be manufactured in the United States.

Leaflets and petitions circulated in the plants, autoworkers proudly wore “No 2 tier” T-shirts on the shop floor, conference calls were organized, comments flooded Facebook and Twitter. After a UAW informational meeting at the Jefferson North plant, some members boldly marched on nearby Solidarity House, the UAW’s headquarters.

With FCA earning a 7.7% profit in the second quarter of 2016, workers overwhelmingly rejected the deal, with all but three locals voting it down. It was clear that the overwhelming “no” vote could be summed up in the demand “Equal Pay for Equal Work.”

The Second Deal

UAW officials were forced to reopen negotiations and let Marchionne know his plan was not acceptable. The second tentative agreement bumped up the signing bonus by $1,000 and dropped the change in health care. But the substantive difference was opening a path from second tier (now termed “in progression” workers) to the wages veteran workers make. Although the agreement required eight years to reach the top, many would get there by the end of the four-year contract. The majority now felt that the principle of equal pay for equal work had been re-established, despite worrying exceptions.

Buried deep in the contract are provisions that set separate wage scales for FCA’s parts workers at Mopar and axle plants. Current Mopar workers can reach parity with other FCA workers, but new hires will be put in a separate scale, their top wage dependent on their division (assembly, powertrain, stamping, etc.) Current and future axle workers who reach the highest wage of $19.86 are eligible for an annual raise of 3% during the contract’s last three years.

Temporary work is no longer limited to covering absences at the end of the week. Already hired “permanent” temporary workers can earn $17-22 while newly hired temps will earn from $15.78-19.28. Thirty-five years ago when I worked at Ford, temporaries were used over the summer to cover the vacation period. With the introduction of the lean production system, the Big Three and the union agreed to have temps fill in on weekends. But where it used to be that surviving on the job for 90 days meant permanent employment, now the Big Three have “permanent” temporary workers, who lack job security.

The revised agreement didn’t address issues such as COLA or the hated Alternative Work Schedule. Nonetheless workers felt they had defeated Marchionne’s plan to lower the wage scale.

Given that the company was the smallest of the Big Three, FCA workers concluded they had gone about as far as they were going to be able to go this time around and voted for the contract.

On to General Motors

Next up was GM. Going into the negotiations the corporation stated it intended to maintain its 10% profitability rate; no UAW official challenged the remark. The tentative agreement offered a moratorium on outsourcing and $1.9 billion in new investments in addition to the $6.4 billion already announced, promising 3,300 jobs at 12 different sites. Of course, there’s always a loophole for management to renege on such promises.

The agreement mirrored the eight-year pattern for moving second-tier workers, representing 20% of GM’s 52,700 unionized work force, to the highest wage. Additionally their health care coverage was raised to match first-tier benefits. At GM even temps are entitled to health care coverage after 90 days–and earn a whopping 24 hours of unpaid (yes, the contract specifies unpaid!) annual vacation time.

While COLA was off the table, veteran workers were to receive annual wage increases similar to the Chrysler agreement. The signing bonus of $8,000 was available to both–and even temps working more than 90 days would receive $2,000. As at Chrysler, additional sweeteners were various bonuses and profit-sharing payouts. Throwing money at workers is cheaper than reinstating COLA, where the increase is imbedded in the wage and compounds over time.

Along with these temporary tiers, the agreement outlines an “exception” to the UAW-GM agreement in four GM parts plants because of “unique operations and competitive environments.”

If second-tier wages are being phased out, at the same time more tiers have been created. Workers in different GM plants will have different rates of pay, and temp pay rates depend on one’s hiring date.

By the end of the voting process 58.3% of production workers voted “yes,” but 59.5% of skilled trades workers voted it down. Tradespeople, who vote separately because they have unique issues, opposed GM’s continued drive to reclassify and reduce the trades, forcing them to perform multiple jobs without proper training, outsourcing the work or sometimes forcing them to take production jobs. Many felt GM was skimping on the apprenticeship program.

In 2013, when Chrysler skilled trades voted the contract down, the UAW leadership, after a hasty consultation with local officials, declared the contract ratified. This time the leadership held up ratifying the agreement and had local meetings to identify their objections. Two weeks later Dennis Williams announced the contract ratified, stating it had been modified to protect certain core job classifications and seniority rights. However, the modified agreement was not sent back to the trades for a final vote.

Ford Workers Vote

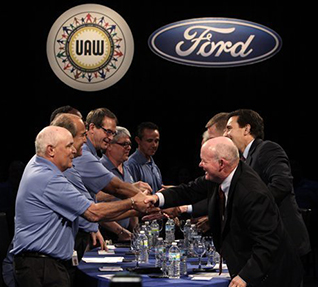

UAW officials and Ford representatives at the beginning of contract negotiations.

While the UAW consulted with GM skilled trades workers, the UAW/Ford tentative agreement had been released to Ford’s 53,000 union members. Unlike GM and Chrysler, the corporation did not go through bankruptcy. Early in 2009 it asked its workers to make sacrifices to get through a difficult period. Ford workers agreed to suspend COLA, several bonuses and a minute of break for every hour of work. But when Ford later asked for a second modification, including suspension of the right to strike, workers voted “no.”

Since 2009 Ford posted $48.36 billion in profits, $6.8 billion in 2014. Ford’s profit margin, at 11.1%, is the highest of the Big Three. Nonetheless, the UAW/Ford agreement differed little from the GM one–just slightly more bonus money and the promise of a $9 billion investment.

Under the previous contract, whenever the second-tier workforce exceeded a 28% cap, the most senior of them immediately graduated to first-tier wages. Earlier in the year 808 second-tier workers had been reclassified and another 338 will move as well, but given that the new contract adopts the eight-year pattern, 15,137 will be placed in that lengthy process.

Parts plants were marked off as “exceptions” with lower wage scales, as were the temps. As Scott Houldieson, Vice President of UAW Local 551, wrote, “This is part of the plan to keep us segregated. A segregated workforce doesn’t stand together in the face of intimidation. A segregated workforce won’t work together to fight wage suppression.”

The “no” votes at Ford ran at 53% until the very last day. Throughout the process Jimmy Settles, UAW Ford Vice President made it clear that if the agreement was turned down, he could not negotiate a better deal. (In 2011 he announced that if the agreement was turned down, the UAW would call a strike and Ford would call in scabs.) A former first vice president of Local 600 and then director of the region, Settles also predicted that the outcome of the election would be determined by the votes at the Ford Rouge complex. Having been dogged all week by various UAW officials roaming through the plants, telling them how great the agreement was, workers at Dearborn Truck, Dearborn Engine, and Dearborn Diversified voted in large enough numbers to meet Settles’ predictions. The national agreement was approved by 51%-49%.

What’s Next?

Over the course of the long ratification process, workers experienced a sense of power as they forced the UAW to go back to the table at both Chrysler and GM–and got a better deal for it. Standing together and insisting that second-tier workers have a path to the traditional wage produced a victory, particularly in the face of Sergio Marchionne’s alternative. But this round of bargaining saw the smallest and least profitable corporation setting the basic pattern for the Big Three contracts. It also established a multi-tier wage system and kept COLA and working conditions off the table.

The media presented the passage of these agreements as a big victory for the country’s 145,000 unionized autoworkers. Their conclusion seemed based on the size of the big bonuses. “Contracts show split between vets, newbies,” a peculiar roundup article by Alisa Priddle and Brent Snavely in the November 29th Detroit Free Press, attributes the rocky road to ratification to higher expectations by the newer workers–but by themselves they clearly didn’t have the numbers to vote the agreement down. In quoting Jimmy Settles at a press conference just two days before balloting ended, the reporters seem to agree with his analysis: “We hired a lot of people in a very short period of time. And for many of them, this is their first job. And they don’t understand the process.”

The arrogance of this statement by a UAW official is breathtaking! First of all, the UAW does not “hire” at Ford, management does. The truth is that both first- and second-tier workers sought an end to the terrible inequity they experienced on the job every day, and felt that the industry could well afford it. Unity was key. The reporters did note the difference between what UAW officials wanted in this contract–to bridge the gap–and what autoworkers were demanding, to eliminate the gap.

While pointing out that according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics wages in the auto sector have declined 21% in the 2003-2013 period, the reporters latched on to an analysis that workers win progressively more contract after contract. They quoted labor professor Arthur Wheaton, who saw in autoworker demands ”a symptom of a misinformed and untrusting membership…I think it was that they didn’t understand the history of the bargaining–that it is a building block, you do it step by step.”

Send that labor prof to work in an auto plant! The history of wages, benefits, and working conditions is not a continuous step forward, but the result of class forces in what is today a globalized industry. In a crisis, workers are blackmailed into making concessions to keep their jobs. Then the corporation uses them to claw back to recovery, rewarding shareholders and top management and stiffing the workers. As Gary Walkowicz, bargaining committeeperson at Dearborn Truck Plant, wrote in a leaflet he distributed, “It does not repay us for all the concessions we have given up. It does not even bring us back to the standard of living we were at before the concessions started.”

The post-World War II period of building upon one contract after another is long gone. Autoworkers never recovered from the concessions agreed to in the 1979-81 period. Today contracts veer from a round of concessions in one fell swoop to a partial recovery. In this neoliberal world, companies want workers to keep wages low and reward them with bonuses when the company is particularly flush. They do not want workers to feel “entitled” to wages and benefits. As a result, workers feel less confident. If they win, as the Chrysler workers did, a way out of two-tier, then they feel that’s all they can manage to do this time around. They are not supposed to notice that there is something wrong when a four-year contract outlines an eight-year process.

The strategy of pressing their advantage seems reckless. And the fact that UAW officials at both the national and local level counsel caution makes it difficult to have any confidence that the bargaining team is capable of striking a better bargain, even in the most opportune moment. It’s hard to imagine how a fight against these corporations can be waged by a leadership that feels workers should be happy to have a job. But rebuilding a militant culture isn’t easy, even after the kinds of discussions that took place this time. Will militants run in the next round of elections and begin to offer an alternative as they take office? A space has opened up, but will it be enough?

Interestingly, one legacy from the struggles of the oppositional New Directions caucus led by Jerry Tucker against concessions in the 1980s and early ’90s was the right to read the actual contract language, not just the summary the bargaining committee drew up. In both 2011 and 2015 these were available on the UAW website.

While both the union and corporation tried to present the multi-tier wages for temps and parts workers as “exceptions,” this looks like a cancer that will spread, as does the use of temps.

How can the lower-wage scale in the Big Three parts plants be an inspiration to the unorganized workers who make up 85% of the auto supplier work force? Or to the unorganized workers at Toyota, Honda, Volkswagen? Or to autoworkers in states like Michigan and Indiana, where right-to-work laws can misdirect workers’ frustration over conditions on the job?

There are still deeper problems: Given what we know about the role fossil fuel plays in causing climate change, the annual production of 16-18 million U.S-made vehicles is not sustainable. These lines need to be rapidly phased out and replaced with an industry manufacturing buses, light rail, and some electric vehicles. Clearly that’s not going to happen as long as capital drives the industry and without worker and community control guiding the conversion.

There’s a lot for autoworkers to be thinking about and organizing around!

Dianne Feeley is a retired autoworker active in Autoworker Caravan, a rank-and-file caucus, and an editor of Against the Current.