Folko Mueller

Posted September 12, 2024

Earlier this year, on January 31, 2024, an article of mine titled “Never again is right now!” was posted here in the Solidarity Webzine. In it I discussed some major demonstrations that had just taken place in Germany as pushback against a secret AfD [the far-right Alternative for Germany party] meeting with other European fascist representatives on the forced deportation of immigrants. I also mentioned polls that predicted that the AfD would win 30 percent or more of the vote in the three Eastern German states that were going to have elections in September. Two of the three elections, in Saxony and Thuringia, just occurred on Sunday, September 1, and, unfortunately, the predictions proved to be accurate. The results constitute nothing less than a shock to the German political system, which had for the longest time been based on a consensus-oriented political culture gravitating towards the center.

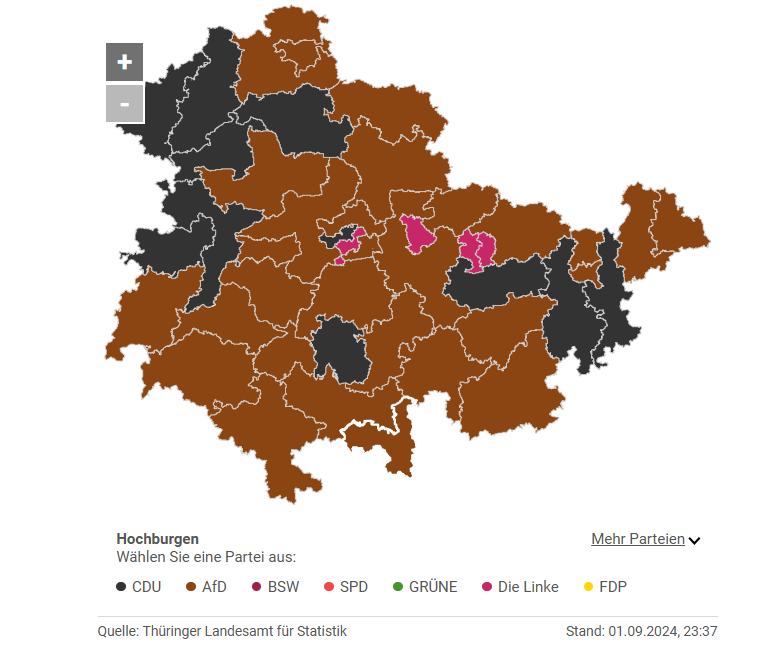

In Saxony, the AfD gained three points and came in at 30.6 percent. Only the center-right CDU got more votes with 31.9 percent. In Thuringia, the AfD won the election with 32.8 percent and thus made history, just as it had encouraged its voters to do during the campaign with its slogan “Schreib Geschichte!”, that is “write history!”. This is the first time in post-WWII Germany that a far-right party has won a state election. The CDU came in a distant second at 23.6 percent. The impact of this cannot be overestimated. The liberal weekly newspaper Die Zeit summed up the results as follows: “This day will change the country — in its debates but also in its political decisions.”

AfD did surprisingly well among young voters

A serious concern stems from the fact that the AfD fared very well among young voters in both Thuringia and Saxony. According to Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, a German non-profit elections research group, 29 percent of people between the ages of 18 and 29 voted for the AfD in Saxony. In Thuringia, a staggering 35 percent of the same age group voted for the AfD. This is a sign that, for this particular demographic, this far-right party is not at all stigmatized. On the contrary, it can be interpreted as a normalization of the AfD among young voters, who apparently perceive the classic division of the party landscape into left and right as increasingly not important. As the researcher Rüdiger Maas, who studies generational trends, mentioned to the German Press Agency (dpa): “This means that these extreme parties don’t slip to the margins.”

Die Linke continues to be in free fall

The single biggest loser in both state elections was, unfortunately, Die Linke. It came in at 4.5 percent of the vote in Saxony, which represents a loss of 5.9 percentage points vis-à-vis the last state election of 2019. In Thuringia, Die Linke witnessed a staggering 17.9 percentage point loss! It came in fourth, with 13.1 percent of the vote, in a state it had ruled for a decade! A direct beneficiary was the narcissist Sarah Wagenknecht’s new BSW party, which is named, of course, after her. They pretty much absorbed all of the loss and got 15.8 percent of the vote in their first election performance ever.

BSW — splitting the left in Germany further

The BSW is consistently labelled as a left-populist party by German news pundits. At first glance, their program may give the impression that this is perhaps the case. Their program consists of four cornerstone ideas:

Economic Rationality — basically an appeal to a return to the good old days when the market economy supposedly worked: “We strive for an innovative economy with fair competition, well-paid, secure jobs, a high proportion of industrial value creation, a fair tax system and a strong middle class (Mittelstand).”

Social Justice — the age-old phrase that even the social democrats are known to dust off for every election cycle. Here too there is no critique of the system itself: “We want to stop the disintegration of social cohesion and realign politics with the common good. Our goal is a fair meritocracy with real equality of opportunity and a high degree of social security.”

Peace (Foreign Policy) — “Our foreign policy is in the tradition of Chancellor Willy Brandt and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, who countered the thinking and acting of the Cold War with a policy of détente, reconciliation of interests and international cooperation. We fundamentally reject the resolution of conflicts by military means.” So far, so good.

Freedom (Strengthen Democracy) — “We want to revive democratic decision-making, expand democratic co-determination and protect personal freedom. We reject right-wing extremist, racist and violent ideologies of any kind.” Again, this is something left-sounding that most of us could get behind.

However, if we dig deeper, we can observe that the “Peace” cornerstone in practice oftentimes translates into a very campist pro-Putin line. This includes Sarah Wagenknecht’s “peace rally”, which she held in early 2023 and was one of the defining moments of her final break with Die Linke. Although obviously pro-peace, Die Linke feared that this event would attract Trumpesque strong-man (Putin) lovers as well as other outright fascists and thus did not endorse it. It turned out that Die Linke was entirely correct in this assumption.

Similarly, if we dig into the last cornerstone, we can see why the AfD has been trying to invite Sarah Wagenknecht to become an ally. The narrative for “Freedom” reads further down: “Immigration and the coexistence of different cultures can be an enrichment. However, this only applies as long as the influx is limited to a magnitude that does not overwhelm our country and its infrastructure, and as long as integration is actively promoted and succeeds.”

In addition, it attacks any diversity, equality and inclusion efforts: “Cancel culture, pressure to conform and the increasing narrowing of the spectrum of opinions are incompatible with the principles of a free society. The same is true of the new political authoritarianism, which presumes to educate people and regulate their lifestyle or language.”

It is for these reasons that I would not consider this a “left populist” party in the sense that we are historically used to. While their program certainly contains elements that appeal to progressive voters, it also has tenets that are clearly targeting potential AfD voters.

Katja Wolf, BSW’s top candidate in Thuringia, left Die Linke and joined BSW to prevent an AfD win in Thuringia precisely with these elements of right-wing, not left-wing, populism. Clearly, this did not work out and rather than keeping the AfD from winning, it has done lasting damage to Die Linke and Germany’s left as a whole for the benefit of a single person’s ego. At least partial blame for the success of the AfD lies with Sarah Wagenknecht’s new party.

What next?

In essence, we have very much the situation of a hung parliament in both states. In Thuringia, where the AfD got the most votes but not a ruling majority, the party will be hard-pressed to find any coalition partners and will therefore most likely end up in an opposition role. However, with over one third of the seats in the local parliament, it will have tremendous power and the ability to block even as a minority. It could, for example, prevent that:

- the public can be excluded from the state parliament (as the source explains, this almost never happens, it’s included in the list just for completeness)

- the state parliament dissolves itself

- the President of the State Parliament is voted out of office

- Judges are being appointed to the Thuringian Constitutional Court

- a parliamentary control commission is set up

- the Thuringian Constitution is amended

Source: https://www.mdr.de/nachrichten/thueringen/landtagswahl/sperrminoritaet-afd-100.html

Likewise, in Saxony, where the CDU was barely ahead of the AfD, the CDU will be hard-pressed to scramble enough coalition partners to sideline the AfD, although it appears that after a software error and a minor seat recount, the AfD no longer has a blocking minority in that state. Nonetheless, the CDU will have to enter a coalition with the BSW and maybe even Die Linke itself, to get to a majority that could actually govern. While the first possibility is highly unpalatable for the conservatives, the second one is technically not even “allowed” according to the CDU’s own statutes: “The CDU of Germany rejects coalitions and similar forms of cooperation with both the Left Party (Linkspartei) and the Alternative for Germany.” [Decisions C76, C101, C164 and C179].

I have discussed elsewhere, however, how at least on a municipal and even state level these decisions have already been violated in practice without being challenged. There is also a somewhat vague provision in their statutes regarding non-cooperation with both the AfD and Die Linke: “At the same time, however, we know that certain points of contact cannot be avoided in everyday parliamentary life. After all, both parties were elected, they are democratically legitimized and their rights arising from the will of the voters must of course be respected.”

It remains to be seen if the CDU’s principles will remain as steadfast as the AfD continues to rise in popularity. The remaining state election for this year will be in Brandenburg on September 22, where similar results have already been predicted. Should the AfD win big there as well and the social democrats of the SPD suffers another heavy defeat, it may even be likely that chancellor Scholz, a social democrat, will have to step down.

After that, all eyes will be on the upcoming general election in September of next year. With BSW gloating over their success and with no intention to pull out of future races, despite already having apparent staffing issues, and with both Die Linke and SPD in shambles, Germany will face another rocky upcoming year politically.