Posted May 11, 2008

The artist must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery. I have made my choice – I had no alternative. – Paul Robeson

Atlanta lost another piece of its cultural and political history sometime this winter when the “Wall of Respect” mural on Auburn Avenue was literally whitewashed. This came to my attention in mid-December; it could have been gone before then. A little over a year ago, I researched the Wall of Respect, and other political murals in Atlanta, during my last semester at Georgia State University. I’ve been meaning to write something to memorialize this artwork, and its destruction, since noticing it was gone. Yesterday, the Sweet Auburn Festival (you have no idea how much Shea butter can be sold on one street unless you’ve been) reminded me I needed to do so. I want to start with a short survey of some ideas about art under capitalism, and the role of art in social movements and revolution.

Art and Capitalism

Art is not mere paint on a canvas. Like all forms of culture, visual art is a product of its time, and reflects the contradiction and social conflict of that time. But this goes beyond the artist’s choice of subject matter, symbolism, or visual style. The artist is a worker, and like all workers under capitalism, she is forced to sell her labor to survive – as the language of “the starving artist” and “selling out” suggest. Art, therefore, also represents several social relationships: the producer, the owner of the work, and the consumer. In societies without rigid class hierarchies, each of these roles was fulfilled collectively: art as a social product, to be controlled and enjoyed communally.

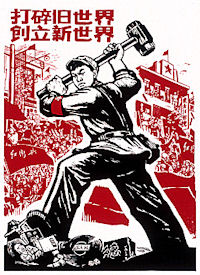

Art and culture are also not static. The way that art is produced, enjoyed and interpreted changes dramatically according to the economic state and political agenda of the working class, women, racial minorities and so on. Revolutionists from Trotsky to Mao and many in between have grappled with the role that art plays as both a “mirror held up to society” as well as a hammer with which to shape society (to paraphrase German marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht). I come more from a Trotskyist way of looking at things, so maybe readers more familiar with Mao could elaborate on his evolution on this question. The Little Red Book distributed during the Cultural Revolution has a few thoughts. Prior to the Chinese Revolution in 1949, Mao stressed that “all literature and art belong to definite classes and are geared to definite political lines” and that political artwork “prepares the ground ideologically before the revolution comes and is an important, indeed essential, fighting front in the general revolutionary front during the revolution.” During the Great Leap Forward, in the 1950s, he argued that “different forms and styles in art should develop freely and different schools in science should contend freely. We think that it is harmful to the growth of art and science if administrative measures are used to impose one particular style of art or school of thought and to ban another.” I am not sure how to contrast this with the generally wooden, standardized and uncreative “socialist realism” art made during the Cultural Revolution, though…

Diego Rivera and Trotsky on Art

Probably my favorite piece of artwork is the monumental Diego Rivera mural, “Detroit Industry.” Long ago, before seeing it in person, I’d only seen crops of the center panel and always assumed it was a kind of workerist circle jerk, like, “Check out these badass autoworkers, dancing around with giant tools, isn’t the proletariat awesome?” There is nothing that compares to being surrounded by four walls of beautiful frescoes – the experience is something like a Sistine Chapel for materialists – but if you click on these photos you can see that in fact the mural is not about workers but about everything: geology, geography, reproduction as well as production, cooperation, cooptation, human passion, possibilities, and limitations… the fact that the social process of automobile production is inseparable from the whole of human history.

Diego Rivera was influenced politically and artistically by Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Trotsky saw all art – even art produced under the exploitative and oppressive capitalist system – as representing not just the viewpoint of a particular class, but all of the contradictions and struggle inherent in class society. In Literature and Revolution, written during the explosive early period of post-revolutionary Soviet society, Trotsky argued “revolutionary art… reflects all the contradictions of a revolutionary social system, [and] should not be confused with socialist art for which no basis has as yet been made. [my emphasis]” After the triumph of the working class – the socialist period of majority rule during which the road to classless society is paved – he cautioned against attempts at “socialist” art. “There can be no question of the creation of a new culture, that is, of construction on a large historic scale … there is no proletarian culture, there never will be any, and in fact there is no reason to regret this. The proletariat acquires power for the purpose of doing away forever with class culture and to make way for human culture. We frequently seem to forget this…There is no real analogy between the historic development of the bourgeoisie and of the working-class.” My weak attempt at summarizing Trotsky’s views towards art (which are very much in line with Engels and Marx’s) would include:

- Recognition that all art reflects the contradictions in society. Since capitalism intensifies the contradiction of social production and private ownership, most people are sealed off from creating (and enjoying) art, and artists cannot create truly free art under the current economic order. Just look at what happened to hip-hop…

- The message of art comes from its emotional, rather than purely intellectual appeal. All art has political content, but good artists are not propagandists, and we should demand “political” art that is aesthetically challenging and thoroughly infused with its politics, not just a wrapper for a political message.

- A revolutionary society inherits the intellectual and artistic legacy of the old society; the tasks of revolutionary artists should not be to destroy bourgeois society but to synthesize its best aspects on the path to social transformation (for example, Marxism synthesized and transcended bourgeois theories of utopian socialism, economics, and philosophy).

The interplay between cultural production and the larger African-American freedom movement, which was both a class movement and a movement for national liberation, is more complex and really deserves its own entry – especially with the recent passing of Black consciousness pioneer Aime Cesaire. Robin Kelley (especially in his book “Freedom Dreams”) and Komozi Woodard (in “Amiri Baraka and Black Power Politics”) both have interesting stuff to say… but for now, on to the mural!

Towards a People’s Art: Muralistas of the ’60s and ’70s

Dealing specifically with the mural phenomenon of the 1970s, Eva Cockroft’s amazing book Towards a People’s Art presents an excellent critique of the “radical” avant-garde and postmodern art movements of the Vietnam era, which attempted transcendence while remaining firmly dependent on patronage and gallery/museum system (and therefore rooted in the capitalist mode of artistic production.) Instead, she celebrates the tradition of political murals born in revolutionary Mexico and brought into working class communities, ghettos, and barrios of the United States in the late 1960s. Muralists challenged the capitalist art world in several ways. Not only were the works beautiful commemorations of people’s history and progressive values, but to the extent that a mural involved large numbers of people in its design and production, they were valuable organizing tools, as well.

I’ve long been more interested in murals than graffiti, which infatuate many young radicals. In some ways, graffiti does represent an attack on capitalist property relations. As an organizing tool or prefigurative model of how art can play into social transformation, however, the macho, vigilante style of many graffiti writers is instead an (understandably) nihilistic response to de-industrialization and privatization of the cities. A mural, designed by a skilled artist but planned and produced collectively by a whole community offers a way to overcome divisions of gender, age, language, work, and race in a way that even politically-themed graffiti does not.

The original Wall of Respect, Chicago.

The most socially significant mural Cockroft discusses was the Wall of Respect on Chicago’s southside. In 1967, a group of artists, many of them “craft” painters such as signpainters rather than “fine” artists, divided the wall into panels that celebrated Black genius and historical achievement. The mural became a community rallying point, especially after it was targeted for destruction by police forces and the city (it was eventually demolished in the early ‘70s).

But the Wall started a movement. In cities and towns around the country, political muralists created their own Walls of Respect in African-American neighborhoods during the early 1970s. In most places the artwork was connected to community struggles and a toehold of Black political power unseen in the southern United States since Reconstruction, and never in most parts of the country. The 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary anticipated the ascendance of Black mayors and other city politicians around the country.

Black officeholders and public art

In 1974, Maynard Jackson was elected mayor of Atlanta. Atlanta has a long tradition of Black political muscle in coalition with the white business ruling class; Jackson was firmly planted in this tradition. His grandfather, John Wesley Dobbs, was an early leader of the city’s Black middle class and organizer of voter registration drives. Jackson’s own mayoralty was largely an agreed-upon political transition for the city’s ruling coalition, the fact that it occurred an election earlier than the white ruling class was comfortable with depended on mobilization at the polls by the Black community. Especially in his first term, Jackson repaid this victory with a series of reforms – mostly to the benefit of the Black middle class, but also some concessions to the neighborhood-based community movements.

One of these was increased public funding for the arts expanded through the creation of the Office of Cultural Affairs (later renamed the Bureau of Cultural Affairs) and the Neighborhood Arts Center. [There used to be a great website on the NAC which seems to have disappeared]. The NAC, located in Southwest Atlanta close to downtown, received city dollars and housed visual and performing artists who offered free community classes in the arts. In 1975, three artists associated with these projects – Nathan Hoskins, Verna Parks, and Ashanti Johnson, painted Atlanta’s Wall of Respect. It was the last of these murals to be completed.

click to open full-size

Located on Auburn Avenue, the historical commercial and cultural center of Atlanta’s African-American community (and called “Sweet Auburn” by Jackson’s grandfather) the mural originally decorated a brick wall adjoining an abandoned lot at the intersection with Piedmont Avenue. Each of the wall’s six sections contains a strong visual theme which communicates a series of historical vignettes.

click to open full-size

In the left corner, a saxophonist plays in front of a chained African boy, followed by blue-tinted portraits of Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X and W.E.B. Dubois. Between the blue panel and a full-body portrait of Muhammad Ali, Johnson placed several potent images. The bust of a second anonymous Black child is juxtaposed with the mask and headdress of ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamen. Tutankhamen’s tomb was unearthed during the 1920s when interest and reverence for African history, spearheaded by Carter G. Woodson, played an important role in shaping modern Black Nationalism. A trio of West African ancestor masks placed below the two portraits reinforces the idea of attention to the past. At the same time, a closed fist and outstretched hand in the following panel emphasize continuing aspirations towards freedom.

click to open full-size

The second half of The Wall of Respect features contemporary figures rendered in full-color or black and white photorealism. A young, grimacing Muhammad Ali lunges towards the viewer. To his right, the final panel of the mural depicts Angela Davis, John Coltrane, and an anonymous third figure against the pan-African red, black and green tricolor. At the far right a dedication reads: “To honor, to love, to cherish/ our strong ones alive and those who have perished/ While fighting for truth our souls to protect/ We love you, we give you a wall of respect.”

Community and Development around Atlanta’s Wall of Respect

By 1977, Congress had designated the entire Sweet Auburn district, which contains Dr. Martin Luther King’s birth home, a National Historic Landmark. In 1980 it was upgraded to a National Historic Site. Complex interests competed for a vision of the area: neighborhood residents, the King Center (controlled by Dr. King’s family), absentee property owners, and the city’s own grand plans of nurturing tourism in a downtown badly damaged by white flight. As the Park Service set up office near King’s historic birth home, tension mounted around the fear of bureaucratic control, and potential displacement of politically marginal residents of the area, who were entirely African-American and mostly elderly. Community members formed Concerned Citizens of the Old Fourth Ward and the Auburn Avenue Revitalization Committee, as well as operating through NPU-M, to publicize these concerns and influence the planning process.

In anticipation of the 1996 Olympic Games, the Corporation for Olympic Development in Atlanta (CODA), a project of Maynard Jackson’s return to a third term as mayor, hoped to “break up the Auburn Avenue corridor in a way that might attract pedestrians – during the Olympics and after.” So John C. Calhoun Park and J.W. Dobbs Plaza were constructed, with tourist-friendly markers emphasizing a mainstream narrative of the Avenue’s history (centered on a pristine past that abruptly omits the economic devastation of the 1970s-90s). John Calhoun Park, on the site of what had long been a parking lot, provided benches and green space immediately adjacent to the Wall of Respect. Ashanti Johnson’s son, Yusef, told me that in 1995 Anheuser-Busch paid to refurbish the mural. Homeless men congregated in the park during the day. When I took the pictures above in fall 2006, several bystanders were eager to show off the mural and identify the figures in it.

Destruction of the Wall of Respect

Sometime in 2007 the mural was unceremoniously whitewashed. In efforts to find out exactly what happened, I learned that the official story is that the landlord of the building next store painted over the mural. This seems incredible, given that the mural survived for 32 years, and suddenly disappeared just as a wave of redevelopment hit the neighborhood.

After seeing that the mural was gone, I noticed that the park was also due for “renovation.” This turned out to consist of clearing the trees and benches, an anti-homeless measure. Across the street, where once stood the Palamont Motel, type of corporate welfare locally known as a “Tax Allocation District” was designated to begin tax-free construction of a big condominium building, now complete, with the kind of breakfast restaurant white people like at street level. I learned that the development company, called Integral Group LLC, specializes in “public-private partnerships” which is like an unhappy marriage of public resources and private profit-making, with a really bad pre-nup. Another important legacy of Maynard Jackson’s mayoralty was giving a boost to minority-owned contractors…

The whitewashed wall.

This is not to say that murals are a decisive force in the class struggle. But they are a meaningful “canary in the coal mine,” something we can learn from, enjoy, and should protect.

Comments

9 responses to “Whitewashing Black History”

Well, not really a “tinge of pleasure,” but I do feel a very quick moment of inspiration before some piece of agitprop art. Mostly because I feel a sharp nostalgia for a time – before my own, for the most part – when revolutions were a more a matter of everyday news, daily struggles, and not, as our supposedly ‘postrevolutionary’ common sense tries to tell us today, pieces of a bygone history.

But mostly I feel towards intentionally revolutionary or agitprop art the way I feel towards comic books or video games. Temporarily amusing, but not very durable and life-transforming, as great works of art can be.

Another tack is to flip the question, and ask how is any real art is possible in a monopoly industrial capitalist mass society? Here we can think of Adorno’s famous statement that no poetry is possible after Auschwitz. I wouldn’t go that far, but when I look at the art of the Renaissance, for example, poised on the edge between a feudal society and growing merchantile capitalist world, and compare the aesthetic ‘production’ of today, I have to wonder.

Artistic truths live in ambiguity, nuance, and wonderment. Confrontation with the ultimate questions, like death. Capitalism lives in abstract quantity, destroys particularity and experience, and reduces everything to callous exchange in the cash nexus. Capital lives by stealing more and more time from us; and real art requires lots of free time and practice. The destruction of murals, and the commodification of other cultural realms, is a clear example of what capitalism requires for itself, and what it needs to negate.

got to go for now…

[After reading over what is written below I think that it is very dry, so my apologies for that. Must be in a humorless mood today!]

Yes, you can say that “Black” is significant because the racists have made is so – in somewhat the same way that “working class” is significant because the capitalists seized common land and forced us to sell our ability to work in order to live. It’s true that we are all human beings, but very important social realities (class, race/nationality, gender, and so on) have a life of their own regardless of language choices we might make (white supremacy does not disappear if some white people attempt to “not see” race).

Marxists and others have argued that racism does not primarily operate in the form of individual prejudice or bigotry (although this is certainly worth fighting against!) Instead, the centrality of race with the development of capitalism – a history of slavery for indigenous and African people, extermination and forced removal of indigenous people, super-exploitation of Asian immigrants, direct colonialism or economic imperialism in Asia and Latin America – has resulted in entrenched white supremacy that is woven into the fabric of society.

However, to say that Blackness has meaning only because of exploitation ignores the historical counter to oppression, which has been the formation of a shared national identity among most African-Americans. When the first several generations of African people were brought to the Americas, they were likely to identify with a patchwork of ethnic and language groups (not to mention class backgrounds) in Africa – some of which had been bitter enemies. The shared experience of enslavement, the struggle to communicate, and the human impulse to fight for dignity and collectivity soon birthed a new identity rooted in the American experience (broadly – this process happened all throughout the western hemisphere, with slight variations depending on factors that flowed from the economic and cultural differences of slaveholding societies in Latina America, the Caribbean, and Anglo north America).

At times of mass mobilization and political action, this undercurrent of shared history and culture (a creole of not just African, but also European and American influences – example, Jazz: a musical form performed on mainly European instruments with African meter and rhythym) has sometimes become a conscious political expression of “capital-N” Black Nationalism. Black Nationalists recognize that the liberation of Black people must be based on the collective self-determination of Black people as a people (nation).

So taking that into account, I think that Black history and Black culture are important components for the development of that kind of consciousness. Even more important is the self-organization of Black people and other oppressed groups in order to determine a freedom agenda. One recent attempt is a statement by the Nationalities commission of Freedom Road Socialist Organization/OSCL. (I am not sure if the Nationalities Commission has membership open to people of African descent, all people of color, or all members who are interested in developing that organization’s politics of nationalism)

I have a problem with phrases such as black history/culture/music etc. We do not talk about white/yellow/brown versions of these things. What, e.g. in the phrase “black history”, does the word “black” mean? The reason why “black” is so significant is because the racists have made it so. We have allowed their prejudice to infect our vocabulary. I know it’s very seductive to talk about, Jazz, for example, as black music. But it simply reinforces the separation of groups of human beings by the token of skin colour. When I listen to the Blues, I hear all sorts of emotions, but I don’t hear “black”.

Isaac,

A really excellent article.

Matt

A professor once told me that making radical art in the present moment was practically useless, as “the artists are much more afraid of the bourgeoisie than the other way around.” The whitewashing of the Wall of Respect is just more proof that this isn’t the case. Really great essay Isaac.

I have to disagree with John though, I think some of those Chinese posters are quite beautiful, and what they represent, even if very bluntly, isn’t entirely pernicious. Though maybe my appreciation for them is due to that the contradictions of that period are already well known and in their current context as .jpegs or reproductions their function is to evoke (an admittedly misplaced) kind of nostalgia.

But certainly the murals Isaac posted, the Rivera included, are extremely didactic–are they aesthetically pleasing only because they represent dissidence? And don’t you feel just a tiny twinge of pleasure when you look at that poster of Lenin sweeping the monarchs and robber barons from the globe?

there’s a graffiti writer in atlanta, nevr, who does a lot of political stuff. here’s a piece near my house in… graffiti of MLK, arundhati roy and noam chomsky. don’t see that every day.

(click to make bigger)

karl marx:

malcolm x:

Yes, a great essay, a moving tribute to these murals!

On the general subject of art and revolution – not really related to the murals at all, but thinking of the Mao and Trotsky quotes – I usually feel spiritually poisoned when I hear simple pronouncements from revolutionary leaders about aesthetics. A general rule of thumb for us to follow is to run from anybody who starts going on about “revolutionary art”. I solidarize here with Comrade Lenin, who denounced the Proletkult advocates as destructive idiots, and who urged comrades to popularize appreciation and experience of the classics before anything else.

And look at all the junk produced by Maoist China and Soviet “socialist realism”! Thanks Isaac for criticizing these affronts to human dignity. Clearly products of a political culture of domination, enforced obediance and spiritless homogeneity.

All art should change us, ‘radically’, and in that sense is ‘political’. But the best, most moving, art is, often, the least ostensibly political. Let us not confuse the two realms, or blur them to far into one another, especially before we take care to (re)learn what aesthetic experience, or any experience, is all about in the first place.

——

Isaac’s essay made me think of two books I recommend: Blues People by Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka – a great narrative history of Black music, spiritual and political culture

and

Art and Revolution by John Berger, about the dissident “non-political” Soviet sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, who utterly defied the idiotic prescriptions of “socialist realism”, was thus shut out of the official art world of the USSR, and directly attached Khruschev as “the most uncultured man I’d ever met” at a closed exhibition of his!

This is the most thoughtful and fascinating article I’ve read here yet. Comrade Isaac shows the way. If we keep this up we’ll push MRzine right out of the way!

If you’re interested in more political art, check out some entries from this blog. Scroll down and find articles on radical stenciling, radical murals, and Palestinian posters.

http://asimplespark.blogspot.com/2006_09_01_archive.html

That hurts, viscerally, that literal whitewashing. What a fantastic mural. I am so glad you have photographs of it.

Thanks for the history lesson as well as the theory, Isaac. I enjoyed this. I do think murals have a much better than average shot at being political art, and I understand your critique of the individualist and macho nature of most tagging. Something in me really responds, though, to wholescale walls that are murals, really, done in graffiti style: I would like more creativity, maybe, than simple photorealism, in collectively produced murals.

More Rivera! Find some excuse to post on Rivera and to put up more of your photos.

maeve66 is a middle school teacher in a working class suburb of Oakland.