Luke Pretz

November 27, 2018

Ten years ago the global economy was thrust into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. In the ten years that have passed many working-class people are left asking “What recovery?” And “Whose recovery?” Those questions are asked despite the longest bull market in Wall Street history. With unemployment rate at pre-crisis levels wages are stagnant and barely keeping up with inflation.

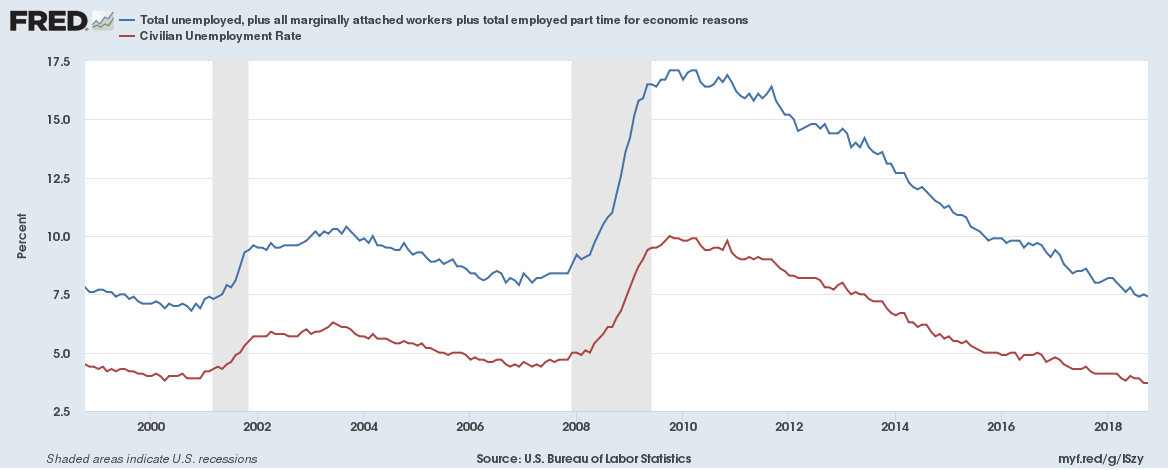

In the worst moments of the crisis workers faced massive unemployment at a rate of 10%, but closer to 17% when we include workers who gave up their search for employment and workers who took on part-time work but desired full time employment. Many working-class people had their homes foreclosed on and taken from them by the same banks who profited off of subprime home mortgage and fraud.

At the heart of the 2008 financial crisis were mortgage-backed securities, financial instruments that were collections of mortgages bought from lenders by investment banks and packaged together as securities for investors to buy. By the 2000s these securities increasingly contained subprime mortgages, loans made to people who would have difficulty maintaining the repayment schedule, meaning that these mortgages were risky for the lending institutions and those who would ultimately hold them in their securitized form. While the mortgage-backed securities had varying levels of complexity, a common thread ran through the vast majority: they were packaged and marketed in a way that masked the quality of the loans that they contained.

Economic crises like the one that happened in 2008 are hardly an anomaly in capitalist society. In the late 19th century the global economy was in a constant state of fluctuation between boom and bust. By 1929 the global economy experienced the devastation of the Great Fepression and faced the double horrors of economic crisis and fascism.

Despite the apparent successes of the post-war period of regulated capitalism and varying degrees of social-democracy, global capitalism came to a standstill and returned to a state of economic crisis in the mid-1970s, creating political space for the neoliberal policy of deregulation and fiscal austerity. Now, well into the neoliberal era of global capitalism, crisis is normalized and occurs with increased frequency. We only have to look back at the housing bubbles and tech bubbles bursting in the 2000s, the recessions of the early 1990s and the savings and loans crisis of the late 1980s to know this.

The sole goal and motivation for capitalism is the search for profits at all costs. To satisfy its existential need for profits the capitalist system must be in a constant state of expansion. The frequent moments of economic crisis are moments where the contradictions of profit=seeking behaviors reveal themselves. As capitalists invest in new more efficient labor-saving technologies to reduce costs, they run up against a dual problem. First, the reduction of profits due to the replacement of human labor, the source of surplus value, with machinery. As the labor time required for production is reduced, so are the potential profits. Moreover, as capitalist enterprises expand their productive capacities while compressing wages and laying off workers, the value embodied in the commodities produce goes increasingly unrealized in money form. This leaves capitalists in a pickle, they have an inventory that needs to be sold but can’t be, and so their capacity to reproduce themselves is slowed or stalled completely.

As socialists we know society can do better than recurring cycles of crisis for workers and expansions that fill the pockets of the owning class. A democratic society which directs its economy for the fulfillment of social needs, individual necessities and desires would remove the need for financial markets, the impulse towards speculative activity characteristic of those markets, and the overbuilding and overproduction necessary for expansion. While the struggle for socialism is a long-term project, we should also be advocating for transitional demands that take back power from the capitalist class and protect workers from the harmful effects of crisis.

This article is an attempt to understand the material roots of the economic crisis. By developing an understanding of the roots of the 2008 financial crisis we can better understand how to fight back and what we need to do to liberate ourselves from a systemic cycle of economic abuse.

Financial instruments

Financial instruments like stocks, bonds, mortgage-backed securities and the plethora of other financial instruments are strange objects. They appear to be commodities like any other, things that are bought and sold in a market, generating profits for financial institutions and their holders. But, when we look a little more closely we see that unlike most commodities there are no workers performing productive labor to make them. Because of that, these commodities do not embody the value-added of workers’ labor in the same way that sneakers, cars or cheeses do. Financial instruments are separated several degrees from the productive process. They are bundles of claims on interest from loans made by lending institutions.

The apparent separation of financial instruments, like mortgage-backed securities, from the productive process gives them an almost magical appearance. They produce profits for their owners without directly exploiting workers or producing a commodity. But when inspected from at the systemic level it’s clear that financial instruments are intimately connected to capitalist production and the circular flow of capital through the economy. Securitized financial assets like mortgage-backed securities act as a lubricant for the flow of capital through the economy in a way similar to loans. They help to ensure that capital, in its many forms, remains in motion. While loans help to ensure that firms have access to capital in the periods between the production of a commodity and the sale of those commodities, purchases of financial instruments like mortgage-backed securities help to smooth the flow of capital for loan making institutions. By purchasing loans from banks financial institutions and consumers take on risk of the loans and recapitalize lenders so that more loans can be made.

There is a fundamental difference between interest-bearing capital, like loans, and financial instruments, what Marx calls fictitious capital. While the interest earned on loans are paid directly out of the profits of a given capitalist, the profits in securities markets are disconnected from production and are claims on claims on future interest payments. What this means for the valuation of financial instruments is that their value is determined by the expected interest rates and, because of their apparent disconnect from the tangible world, are also subject to speculative activities and the pressures of supply and demand for financial assets.

Speculative activities can drastically inflate the value of financial assets. As the price of a given type of security goes up speculative activity becomes, for a while, a positive feedback loop. Investment banks and others buy mortgage-backed securities, their market value goes up, and so they become a more desirable investment and more are purchased at a higher price, causing their market value to rise further, so on and so forth.

But this speculative activity, despite its appearance of being separate from the “real economy,” is nonetheless intimately connected to the material conditions of the economy at large. Financial instruments sit on companies’ balance sheets, in unions’ pension funds, and act as means of payment. Furthermore, since financial instruments are claims on future revenue streams, and in the case of mortgage-backed securities claims on revenue from home loans, their values, despite the speculative activities that surrounds them, are ultimately tied to the “real economy” and the productive activities those revenue streams are based on.

The 2008 financial crisis: material conditions at work

Financial instruments are connected to the flows of capital through our economy and, thus, connected to more tangible aspects of our economy. In the case of the 2008 financial crisis we can see how the development of the neoliberal era created the material conditions for the financial crisis.

The neoliberal arrangement of economic institutions that emerged in the early 1980s was a significant break from the post-war period. It was an attempted return to an unregulated capitalism like that of the early 20th century. This meant the privatization of state enterprises and functions, the erosion of the welfare state, austerity measures, increased intensity of private and public employers’ anti-union activity, the proliferation of “anti-big government” ideologies, the removal of barriers to the free-flow of capital and the large-scale deregulation of the economy. Simply put, the emergence of the neoliberal era under Reagan and Thatcher was a global frontal assault on the global working class that has continued to the present day.

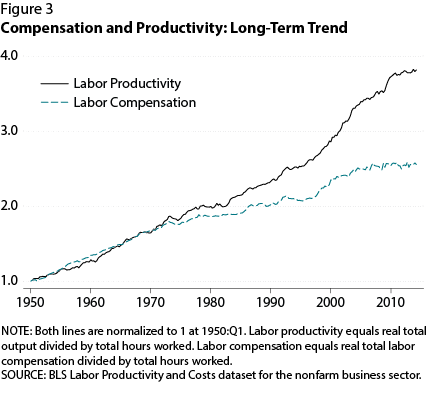

As a result of the attacks on unions, wages stagnated even as they became better educated and more productive. Compounding the stagnating wages were drastic restrictions and clawbacks of social welfare programs and the sharp increases in the costs of healthcare, education, child care, and housing. Over the entire period, increasing numbers of workers were forced into precarious employment. All of this against a backdrop of growing consumerist attitudes and a valorization of money-making as the be-all and end-all of individuals’ existence.

For most, those circumstances meant a significant increase in the out-of-pocket living costs compounded by the social pressure to “keep up with the Joneses.” For the productive segment of the capitalist class, the stagnating wages and increased cost of living are major problems. Without consumers able to purchase the commodities produced, capitalists will be unable to realize the value of those commodities, whether they be new cars, homes, food or education. Without realized profits, they cannot reinvest to expand production. Since, as Marx famously noted, under capitalism, “accumulation … is the Moses and the prophets,” this creates an existential crisis for productive capitalists.

In response, capitalists encouraged growing demand for consumer credit to supplement the purchasing power of consumers’ wages. Beginning in the 1970s, financial capitalists rapidly developed an infrastructure to increase access to credit and transform it into speculative commodities. This development was aided by the government through the deregulation of banking and finance starting in the 1980s.

With increased access to consumer debt and a deregulated financial market the U.S. and global economy became increasingly financialized, a process whereby finance takes on an increasingly important role. By 1989 financial profits made up more than 20% of corporate profits and continued to trend upward during and after the financial crisis of 2008. Driving this trend was the need by financial and lending institutions to move new risky assets off of their balance sheets to increase their access to flows of capital and allow them to lend even more money. This process, paired with the apparent value of financial assets inflated by the economic expansion and fueled by the cheap accessible credit, contributed to rapid growth and dominance of finance capital.

The combined results of financial “innovations” like credit cards, adjustable rate mortgages, and the expanding market for securitized debt was an apparent solution to the crisis of economic growth, stagflation, that took place in the 1970s. With the tools to finance the production of large and expensive commodities like luxury apartments, massive office buildings, or new tech companies and the realization of the value embodied in those commodities through sales and rentals, financial bubbles began to emerge and grow.

The financial bubbles become self-reinforcing, as their speculative value increases, the real economy they are based upon also seems to boom. Loans that seemed risky before appear less risky given the bull market. With the expansion of credit, more capital is deployed in sectors like real estate, where the credit is easily applied, increasing the stock of available housing for sale with no real basis other than debt-driven demand.

The problem with bubbles is that they are often not long for this world. In the case of the real estate-driven 2008 financial crisis the loans made by banks became increasingly risky. The increasing risk was driven by 1) the demand for debt to package and sell from the deregulated finance industry tied to banking and 2) the shrinking pool of low-risk borrowers as consumer debt grew rapidly through the 1990s and 2000s. The consumer debt that drove the economic growth that defined the neoliberal period would be the source of the economic crisis that would also define the neoliberal period. As workers’ credit was overextended against stagnant and increasingly precarious wages, borrowers began to default on the loans at unprecedented rates as home prices stagnated or fell under the pressure of speculative construction.

What made this crisis extend beyond a collapse isolated in the subprime loan and construction industry was the very thing that made the economic expansion of the neoliberal period possible, the financialization of the global economy under the neoliberal economic regime. The large-scale securitization and sale of risky subprime loans transferred massive amounts of risk from the loan originators to investment banks, hedge funds, pensions, retirement investment portfolios, and corporate stock holdings. When the bottom fell out more than just the lenders were forced to deal with the consequences of magical thinking. The sudden evaporation of value that financial assets were believed to contain meant a sudden shock to corporate profits which led to a sudden contraction in production and increase in layoffs, further deepening the crisis

The response to the financial crisis: Capital was bailed out, while we were sold out

The response of the state to the financial crisis was hardly a radical break from neoliberal logic. There were no bank nationalizations, no massive public works programs, no significant expansion of the welfare state, and no overhaul of banking and finance regulations. Instead there was a concerted attempt to preserve the status quo and continue with business as usual.

In the initial aftermath of the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the federal takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the emergency liquidity granted to financial institutions like AIG, the U.S. economy was still in freefall. By the end of September 2008, the U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson proposed a massive $700 billion bailout package. This proposal would eventually be passed in Oct 2008 as the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (EESA) which created the Troubled Asset Recovery Program (TARP).

The goal of the EESA and TARP was to stabilize financial markets through a government intervention that would buy up the “troubled assets” like mortgage-backed securities held by major financial institutions. By buying up toxic assets, thereby exchanging virtually unsellable financial assets for useable capital, the federal government created the necessary liquidity for financial activity to resume as it had before.

This bailout took place against a regulatory atmosphere that remained unchanged until 2010 when the Dodd-Frank Act was passed. Dodd-Frank was a package of modest reforms, a far cry from the Glass-Steagall regulation enacted in the aftermath of the stock market collapse that precipitated the Great Depression. The goals of Dodd-Frank were to consolidate regulatory powers, increase transparency of financial markets, increase consumer protections, define tools for responding to financial crisis, improve international regulations, and introduce the Volker Rule, which sought to prevent banks from using deposits to trade on their own accounts.

The regulations contained in Dodd- Frank are already being rolled back through bipartisan efforts.

By 2018 these regulations would be rolled back by a coalition of Republicans and Democrats in the legislature, as they dropped from the focus of mainstream press and political debate. One could rightly wonder if the Democrats voting in favor of this policy were grateful for the daily barrage of outrages of the sitting president, creating a helpful diversion away from the bipartisan repeal of one of the very few substantive regulations enacted over the Obama era.

Notwithstanding the meager and temporary countercyclical policy of the Obama administration enacted in the immediate years following the Great Recession, such as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, what did not happen was a real bailout of working-class people. They instead saw their retirement funds ruined, homes repossessed as a result of predatory loans, and long-term unemployment and underemployment.

By 2011, the Obama administration and political-economic elite worldwide, pivoted away from modest Keynesian policy towards an acceleration in the neoliberal direction of fiscal austerity. The tightening of government budgets largely targeted social programs that insulate the working class from downturns and economic suffering. Rather than support those most harmed by the economic crisis, the state actively chose to ignore the suffering of millions in order to jumpstart the profitability of the finance industry, effectively hitting the reset button so that we could continue down the same neoliberal path.

Rather than a break from the economic arrangements of the neoliberal period to a new regime of capitalist management, as after the crises of the 1930s, we now see a deepening commitment to the neoliberal agenda and a recovery that has resulted in few gains for the working class.

Could the capitalist state have taken another course of action? Certainly they could have nationalized banks, deployed huge amounts of capital for WPA-style public works programs and expanded social programs. Both the Great Depression and the Great Recession were the result of the a credit-fueled financial bubble under a neoliberal and unregulated economy. What was different and created the conditions for a substantially different response was the social conditions.

In the 1930s there was a militant labor movement, a growing socialist and communist movement, and the recent history of the Russian Revolution. With growing militancy in the U.S. and globally, governments responded in one of two ways in order to preserve capitalism: the implementation of social-democratic programs or a turn towards fascism. In the U.S. a social-democratic turn manifested itself in the Roosevelt administration’s New Deal.

The conditions were drastically different in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Atrophy in the post-WWII period and three decades of neoliberalism had substantially weakened the labor movement. The disintegration and splintering of the U.S. socialist and communist organizations after the 70s meant radicals and revolutionaries were unable to mobilize and propagandize people in the ways they were able to during the Great Depression. While some heroic attempts were made during the explosion of Occupy Wall Street encampments across the U.S., it was far from sufficient to take the radical transformative action that was needed.

What will it take to overcome the boom and bust cycle that capitalism is predicated on? Looking back one thing is clear, sustained mass struggle led to the gains won by the working class like social welfare programs, protections against discrimination and other civil rights. But also revealed by history is that as long as capitalism has been the dominant economic arrangement the power of the capitalist class remains and is used to claw back many of the gains made by workers.

What is necessary to permanently escape the devastating cycle of boom and bust is a commitment to build a movement to totally transform the way we relate to one another in the economy. A transformation from a capitalist society based on profit and accumulation to a socialist society based on the fulfilment of human needs and the democratic management of the economy by all.

The Socialist solution, why it’s necessary

What the 2008 crisis revealed, as crises always do, is the fundamental instability of capitalism as a whole. It demonstrated the lengths that capital will go to to ensure steadily expanding production, even at its own peril. Similarly, the response to economic crisis reveals the commitment of the state to the preservation of capital, whether it be the implementation of a package of reforms for workers to stave off revolutionary pressures and the support of productive industry through public-works programs and war or through the deregulation of finance and banking to insure the steady flow of capital through the economy.

The fundamental instability and the tendency of capitalism towards crisis and the state’s role in supporting and maintaining capitalist accumulation should come as no surprise. Capitalism is a system that requires ever-expanding productive capacity, capital, resources and markets for those goods. Capitalists are compelled to produce at ever-expanding rates with an emphasis on cutting labor cost, much as we saw in the neoliberal period and the buildup to the 2008 housing bubble.

At its core capitalism is driven towards crisis, even the so-called Golden Age of the 1950-70’s capitalism was punctuated by stagnation and crisis. As socialists we know society can do better than a system predicated on profit, rather than meeting human needs, and characterized by regularly occurring crisis as a result of the sole focus on profit.

As socialists we think that a society democratically organized around production for human need and human development, not for profit, would be able to overcome the frequent crises which are a feature of capitalism. By producing for social need in an intentional, deliberate and planned manner we would bypass speculative short-run profit-seeking which gives rise to bubbles.

As revolutionary socialists we understand that this would be a radical break from a society based on private ownership of the means and tools of production to one organized around social ownership. We also believe that this radical break, to be successful, must be from below through a massive movement for socialism led by the broad working class, not imposed from above by the state or a small cadre of revolutionaries.

That sort of movement-building is a long and difficult process and will not happen overnight. As a result there is a need for both reform and revolution. The reforms we should work for in the period leading up to the ultimate break from capitalism should go beyond liberal attempts to build a kinder, gentler capitalism.

Instead, we should fight for transitional demands or non-reformist reforms, reforms that not only give relief to working-class people but also challenge and take back power from the capitalist class, while simultaneously helping the working class gain the experience and knowledge necessary to self-manage. These sort of demands not only challenge and take back power from the capitalist class but also give us concrete demands to organize around as socialists build power and gain confidence.

Examples of such demands include:

- Guaranteed employment, a living wage for all and the nationalization of key industries fit the non-reformist reforms bill by eliminating the potential harms of being fired and ensuring a high standard of living for all.

- A full employment and nationalization program could be paired with a demand to mobilize workers and productive capacities to combat climate change and rebuild our crumbling and inefficient infrastructure.

- The decommodification of human necessities like health care, housing, food, water and electricity and ensuring universal access for all. Achieving any of those demands would increase our abilities to intentionally act in conflict with the capitalist class with less fear of the consequences of job loss.

Finance and banking is an often overlooked area for the development of transitional demands. While on its surface capitalism appears as though it operates without a planning mechanism, finance plays an important planning and coordinating role in the capitalist production process. Economist J.W. Mason provides an excellent overview of why this is the case and provides a list of reforms, some reformist, some non-reformist, that socialists ought to be demanding, including:

- Public provision of basic banking and finance services through the development of postal banking, free public payments services (e.g., Venmo and Paypal), and greatly expanded public retirement insurance for all. Such reforms decommodify the financial transactions all of us perform on a day-to-day basis.

- A drastic narrowing of the scope of what finance can and cannot do by strictly limiting the types of activities and assets that finance can hold and sell. In moments of crisis the state should protect functions essential to the lives of working people, like the withdrawal of money and the other bookkeeping functions of finance, rather than protecting firms. Further, the state should require private finance and banking institutions to hold substantial portions of public debt, federal, state and municipal. Finally, we should disempower shareholders from controlling firms to decrease the pressure on management to prioritize short-run profits over the long-run health of the firm, its employees and the consumers it serves.

- The democratizing and politicization of central banking. In concrete terms this means doing things like directing the Federal Reserve to use its powers to buy up privately held municipal debt to protect cities like Detroit from financial vultures. Such actions could liberate municipalities to implement development for the people rather than finance and profits. But, ultimately we should be demanding the nationalization of banking and finance and the delivery of democratic control of banking over to the working class and thus the capacity to direct investment.

For socialists reforms of any sort should not be the end goal we should see such reforms as part of the process of building a movement to transform our society. The revolutionary break from a society based on private property, commodity production and profit-seeking to one based on production for social need, the total decommodification of society and ultimately a society where production is intentionally and democratically directed. The democratic planning of the economy removes the basis for the speculation that gives rise to overproduction that gives rise to regularly occurring crisis under capitalism.

Luke is a Marxist economist and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and is a member of Solidarity and the Democratic Socialists of America. He lives, works and organizes in Kansas City, Missouri.

Comments

2 responses to “The 2008 Financial Crisis: Where it came from, what happened after, and what it says about the need for socialism”

I agree with the substance of Luke’s statement’s but question narrative elements.

As a historian I don’t agree that “global capitalism came to a standstill and returned to a state of economic crisis in the mid-1970s, creating political space for the neoliberal policy of deregulation and fiscal austerity.” Contrary to mythology, U.S. economic growth in the 1970s equaled that in the 1980s. The conflicts that led to the elections of Thatcher and Reagan AT THE END of the 1970s were as much cultural and foreign-policy oriented as economic. Economies continued to boom in the Far East and also the developing world, buoyed by high commodity prices.

I believe the rise of neoliberalism dates more from the 1990s when the fall of the Soviet Union freed the capitalist class from a very powerful advocate (however flawed) of the needs of working people. From this period dates the Republican Party’s surge to congressional power in 1994, Bill Clinton’s and Tony Blair’s commitment to “Third Way” policies, and (most importantly) the unification of Europe under a single currency governed by Germany’s excessive fear of inflation.