David Finkel

Posted May 17, 2023

Going forward, I would once again have to grope my way through darkness, in search of truth, understanding, and forgiveness. But I would not go quietly into that dark night as so many others had done. No, I would find a way to rise to the occasion. I would write my story. I would reach into the pain of my experience and share the shame that comes along with being poor, unequal, and despised. And I would tell of the unexpected victories, the deep and daunting discoveries, and more. In short, I would live my life while it was still mine to live; and fear no evil, not even the shadow of my own death…

Keith LaMar, Condemned (2014 and 2018), p.195

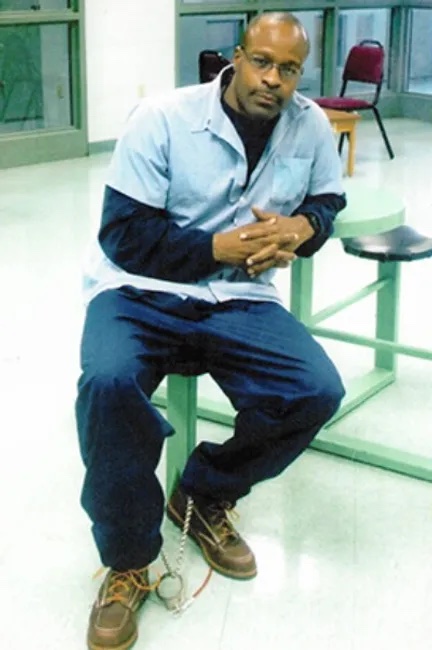

Keith LaMar continues to write and live his story. A death row prisoner in Ohio, facing a scheduled execution date of November 16, 2023, several features of his case command attention — beginning with being held for nearly 30 years in indefinite solitary confinement, a condition that Amnesty International identifies as torture, while continually maintaining his innocence.

There’s also the background of an exceptionally violent, now largely forgotten prison uprising; the remarkable person, author and artist that he has become; and a team of cultural workers spearheading the struggle for Keith’s exoneration and freedom.

“Music,” says Keith, saved him from despair and self-destruction in the hell of prison, especially the music of John Coltrane and Trane’s classic suite A Love Supreme. In the past year he collaborated with Catalan jazz pianist Albert Marques to produce a CD titled “Freedom First.”

On the album LaMar, from his prison location, reads original poetry and commentary interwoven with various instrumental ensembles led and arranged by pianist Marques, including saxophonists Salim Washington, Xavier Del Castillo and Caroline Davis; trumpeter Adam O’Farrill and flugelhornist Milena Casado; vibraphonist Patricia Brennan, bassists Scott Colberg, Walter Stinson and Manel Fortia; drummers Zack O’Farrill and Marc Ayza, and other instrumentalists and vocalists on several tracks.

The fourteen performances include Coltrane’s spiritual compositions “Alabama,” written in the wake of the infamous Birmingham church bombing, and “Resolution” and “Acknowledgement” from A Love Supreme, Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro-Blue” which also became a Coltrane staple, and Marques’ own compositions.

While there’s a rich jazz tradition of performances dedicated to the freedom struggle — think of Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln’s We Insist. The Freedom Now Suite among many others — I know of no other collaboration like this one. It’s important here to emphasize the high musical quality and sound production of the album — nothing cut-rate about it.

Albert Marques reports, “I am publishing a book in Spanish about the whole story of Freedom First, we are playing this summer again after playing in the U.S. and Latin America, there will be a California and Midwest tour in the fall, and there is an amazing new team of lawyers willing to help Keith.”

An equally unique work for the campaign to save and free Keith LaMar is an interactive sculpture DIGEST, created by Mia Pearlman, on display at the Michigan State University Broad Art Museum. As the website explains:

“The exhibition grows out of LaMar’s experiences and his metaphor for the prison industrial complex as a digestive system designed to consume people and break them down. In the center of the gallery hangs an enormous abstract sculpture that evokes a brick building, both crushing its contents and being crushed by invisible forces. Faceted with materials found in the carceral system like metal wire mesh, zip tie handcuffs, prison blankets, and prison uniforms, DIGEST’s sculptural skin reveals small video screens and audio speakers.

“DIGEST is both a sculpture and a musical instrument, played by the motion of viewers’ bodies: As visitors enter the space and move around the work, they trigger videos of LaMar telling his story and audio of a piano composition in five separate tracks. As more people fill the gallery, these audio tracks come together to form a haunting, rhythmic groove. As viewers leave, the sculpture goes silent, leaving LaMar alone once again.”

If you don’t have the opportunity to visit the museum in East Lansing, photos and a video can be viewed on Pearlman’s website.

The Case and the Conviction

Easter Sunday, 1993 marked the beginning of an eleven-day uprising at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility, known as Lucasville, where it’s located. The story of the Lucasville events is the subject of the prominent historian Staughton Lynd’s 2004 book Lucasville: The Untold Story of a Prison Uprising. Lynd contends that the five men sentenced to death for murders committed during the uprising were, in fact, victims of a gross frameup. (For a review of Lynd’s book see Christopher Phelps, Black and White on the Inside).

A summary account of the uprising and aftermath is available on Wikipedia.

One of the condemned men was Keith LaMar (also known at the time as Bomani Shakur). As the defense campaign’s website www.keithlamar.org states: “In the aftermath of the riot, the State of Ohio was under public pressure to clean up a multi-million dollar mess, one that included the death of a prison guard and multiple prisoners. After investigators trampled the crime scene and contaminated any and all potential evidence, they paid jailhouse informants to put together a false narrative, and withheld evidence that would have proven Keith’s innocence at trial&hellpi; This evidence has never been heard in any court to this day.”

The complex details have become obscured over time, but the unbearable horrors of the prison came to a head over the racist prison warden’s insistence on a tuberculosis test injection containing alcohol, over the objection of prisoners whose Muslim religion prohibited it. When the uprising erupted on April 11, “an unlikely alliance of prison gangs: Gangster Disciples, Black Muslims and the Aryan Brotherhood” took the lead in the occupation (Wikipedia).

Keith LaMar was not a member of any of those groups, nor was he even present in the block where the takeover occurred. Keith acknowledges: “Like most young men in the drug-infested neighborhood where I lived, I got caught up in the drug trade.” In April 1993 he was “23 years old, serving the fourth year of an 18 years-to-life sentence for murder” when he’d shot a former childhood friend, also 19 years old, who attempted to rob him during a crack cocaine sale gone horribly wrong. (Condemned, p.9)

While never a participant in the rioting, Keith’s account of his bewilderment, his experience and what happened to him in the aftermath takes up the first three chapters of Condemned. It offers a window into the U.S. carceral system and the sausage-making process of a miscarriage of justice.

The chaotic uprising and explosion of rage resulted in the gruesome deaths of one prison officer and nine inmates who were accused of being informants. The state, needing to assign responsibility for the murders, found inmates who were willing to make deals by fingering LaMar and four others as “ringleaders.” The lead investigator in the prosecution understatedly admits that the case was “not perfect, and some inmates truly got away with murder.” (Lucasville: What happened at the 1993 prison riot that was Ohio’s longest and deadliest)

Offered a plea deal, Keith LaMar refused because, he says, he was innocent of the killings and in his youthful naiveté believed in the justice system. He was after all guilty of what had put him in Lucasville in the first place. Readers familiar with the way the criminal justice system operates will not be surprised to learn that the trial in rural southern Ohio was marked by suppression of information and the removal of the only two African Americans in the jury pool.

Upon the inevitable conviction and death sentence, Keith in 1995 descended into the hell of the Death Row system, where he was interred for 23 hours a day until a hunger strike in 2011 along with two other death-row inmates won some additional time outside their cells and physical contact with family members. He was able to write to Denis O’Hearn, biographer of the Irish hunger strike martyr Bobby Sands, who collaborated and contributed a Foreword to the first edition of Condemned.

At the present moment, the fight to reopen Keith LaMar’s case is a race against the scheduled November 16 execution date. He is one of some 128 death-row prisoners in Ohio, including the other four condemned Lucasville defendants Siddique Abdullah Hasan (Carlos Sanders), Jason Robb, Namir Abdullah Mateen (James Were), and George Skatzes.

In Keith’s case this is a legal, political and spiritual struggle. Readers can go to www.keithlamar.org for continuing updates as well as information for ordering the book and the Freedom First CD, musical videos, podcasts and donations. It’s a case deserving national and global attention.

Comments

One response to “Keith LaMar: A Struggle for Life and Freedom”

AN UPDATE FROM “JUSTICE FOR KEITH LAMAR”, May 31:

Dear Supporter,

A few weeks ago, Ohio governor Mike DeWine issued a reprieve (delay) of the next three upcoming executions, moving them to late 2025. The problem is that he failed to include the only remaining person facing execution in 2023, Keith LaMar, when he easily could have grouped him in. Leaving Keith’s life in the balance means we now are officially less than six months away from the date they intend to murder our friend; our fight is more determined than it ever has been! We cannot stop in this most crucial time. Ohio knows they used Keith to clean up their mess (just take a listen to The Real Killer Podcast Season 2). They know they will murder an innocent man on November 16th if they continue down this path…We are right now in the throws of important work to bring Keith back into court: combing newly obtained evidence that has been withheld for these past 3 decades! We’re also making a documentary film for release to a major network in the very near future. Keith has been busy giving podcast and press interviews and goes on teaching public high schoolers, all from his solitary prison cell. Indeed, the fight and light is still brightly on!

Today we celebrate the 54th birthday of our dear friend, Keith. If you are inclined to send a gift, be it big or small, a token of love and encouragement to help Keith in his most urgent fight, please go to KeithLaMar.org/donate. We’d love to surprise him this evening by sharing all the love that has flowed back to him! We thank you in advance for your love!

Can’t stop, won’t stop!

The Support Team @ Justice for Keith LaMar (a nonprofit 501c3 organization)