Marian Swerdlow

Posted June 10, 2020

In March, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio dragged his feet closing the city’s schools despite clear evidence of widespread community transmission. His stated reason – that no student had exhibited Covid-19 symptoms – was absurd: it was already known that asymptomatic people, children especially, can be highly contagious. The real reason is that schools play many roles in the social reproduction of labor. Most prominently and immediately, the lower grades provide daycare for working parents, and the upper grades maintain social order by controlling the activity of youth.

More than sixty active (non-retired) school workers have died of Covid-19. It is impossible to know how many of these deaths were the result of de Blasio’s prioritization of keeping the city working over the health and lives of students, staff and their families. Most of the lost were members of the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), which represents – among others – Teachers, Paraprofessionals and Counselors.

Public pressure, prominently a widespread and spontaneous education workers’ sick out, and the organizing toward a coordinated sick out day, forced Governor Cuomo to order the schools to close. Within a week, a NYC Department of Education (DOE) memo, issued while schools were still open, came to light. It directed all principals to conceal from their staffs any cases of Covid-19 reported in their schools.

The difficulties, dangers, and bad faith that school workers, including UFT members, faced in forcing the closing of the unsafe and unhealthy schools points to the uphill battle they face to keep them shut unless and until the reopening can be safe. On May 6, the Chalkbeat blog ominously reported that Mayor de Blasio is “increasingly hopeful” schools can reopen in September, without any discussion of any prerequisites or preconditions.

The leadership of the UFT has laid down some markers, most formally in a petition asking the federal government to provide the funds to meet these conditions:

- Widespread access to coronavirus testing to regularly check that people are negative or have immunity

- A process for checking the temperature of everyone who enters a school building

- Rigorous cleaning protocols and personal protective gear in every school building

- An exhaustive tracing procedure that would track down and isolate those who have had close contact with a student or staff member who tests positive for the virus.

In an April 29 op-ed in the Daily News, UFT President Mulgrew,doubles down on the need for federal aid, “because no state will be able to test and re-test children and adults, to notify staff and students of potential viral exposures, to provide the personnel and supplies necessary for social distancing, screening, and tracing, and to provide the materials needed for thorough cleaning and disinfecting of buildings where infections have emerged.”

On the role of the New York State Government, Mulgrew says, “the state could … [insist] that all students and staff … be tested in August for active or prior exposure to the corona virus.”

On the City level, Mulgrew opines that “In September, medical personnel need to be available at every schoolhouse door to perform rapid temperature tests for all students and staff …” He admits “cases of the coronavirus may still emerge in the schools, where concentrations of students and staff make it difficult if not impossible to practice effective social distance.” and then he muses about a possible “experiment with other options, such as split schedules where students come in … shifts, or on alternate days.” But he makes no preconditions for reopening related to social distancing.

He ends “we are going to insist that no one – student, teacher or family member – should be back in school until protections like these are in place.” The phrase “like these” gives the DOE plenty of wiggle room.

As usual, the UFT leadership has not allowed the rank and file any way to shape its union’s policy. So, what do teachers, counselors, paraprofessionals, and others who work directly with students in the schools, think and feel about when and how to reopen them? Chapter leaders should be holding virtual chapter meetings and/or conducting surveys to let members be heard, and the results should shape the leadership position.

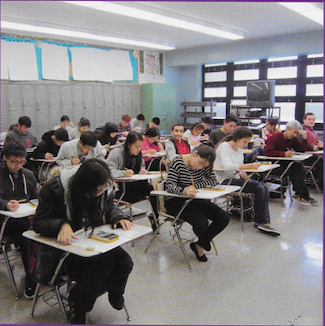

Here’s how chapter members of one large Brooklyn high school responded in a survey to the four conditions in the UFT leadership’s petition, and the discussion in the Mulgrew op-ed.

Only one teacher felt “If all four [conditions in the petition] are followed strictly, then I would be ok with going back to work in the building.” The rest who answered had doubts.

Testing

Many respondents were skeptical that any feasible level of testing could be effective. A science teacher wrote, “The schools can’t test all the students and staff frequently.” Referring to Mulgrew’s condition to “regularly check that people are negative,” an ISS (Special Education) teacher wrote, “How often is ‘regularly’? Is it every week? Every month? Are checks going to be at the school? If so, will they be done under sanitary conditions?” and asked that the union be “more specific” about what regulations it was asking for, “since they are rather vague.” A math teacher was similarly concerned that the UFT’s proposal for “widespread testing” was “very vague.” He thought “once a week sounds reasonable.” A social studies teacher wrote, “I don’t know how possible it is to check the temperatures of every student and staff member every day.” A social studies teacher wrote, “The antibody tests aren’t that accurate and they don’t prove immunity. Someone can be contagious and not have any symptoms.” A counselor wrote, “We have students and families with Covid. Some have no symptoms, but are carriers. These protocols [in the UFT petition] are not enough to protect us.” Another counselor concurred, “Not everyone with Covid has fever.” An ISS teacher wrote, “how sure are we knowing that one person might spread it or not.”

Plant sanitation

Most were concerned about cleaning protocols. “At this point, I am really not sure what it is going to take to get us back to school,” wrote one social studies teacher, “The one thing I am sure of is adequate cleaning of all surfaces in the building. This includes tops of desks, radiators, chalk boards, all door knobs, door handles, banisters and smart boards, as well as mopping the floors with bleach every day, maybe twice a day …” and then cast doubts on how feasible that would be, saying the school “does need some help in the cleaning department.” A counselor wrote more bluntly, “Cleaning in the school is awful. Maybe floors are swept but that’s it.” One science teacher wrote, “When I was in school [before it closed] I asked for something to wipe the tables between classes or at the end of the day. I was told that they did not have the supplies and was ignored. In the end, the school gave two Clorox wipes containers to each department.” These experiences lead him to doubt whether cleaning will be taken as seriously as necessary if schools reopen. He also observed, “They don’t have enough custodial workers to clean the frequently touched surfaces every day.” “Rigorous cleaning protocols are important,” wrote a math teacher, “but who would be doing this, and would they be trained to do it correctly?” An ISS teacher wrote, “I spoke to a custodian when we were still in school and even he thought the materials he was given were a joke … It wouldn’t actually help clean up much of anything.”

Personal protective equipment

One social studies teacher wrote, “face masks are a must.” There was skepticism about schools providing adequate PPE: “If they give students a mask,” wrote a science teacher, “they will lose it before the next day. It’s too expensive. I don’t see the school giving teachers masks.” An ENL [English as a New Language] teacher wrote they wanted “all students and teachers wearing masks, maybe plexiglass around desks.”

Personal cleaning supplies

Many teachers complained that Mulgrew never mentions personal cleaning supplies, such as wipes, sanitizer, soap and paper towels, for staff and students. A Counselor wrote that there must be “hand sanitizing stations throughout the building.” A chemistry teacher wrote, “The one sanitizer dispenser for the school came the day before teachers were to leave the building.” Regarding students washing hands, they wrote, “When they could do this – who knows?” An ISS teacher said “sanitation equipment, like hand sanitizer” should be provided to staff members, “They should not come out of the pockets of staff, especially considering that … these items have been hard to come by.”

Contact tracing

This evoked only one comment. A math teacher wrote, “I have great concerns. I do not wish to have an app on my phone tracing where I go and when … I do not trust the DOE…”

Social distancing

A need for social distancing was a major concern, and a subject of conflicting ideas and feelings. Many felt it was a non-negotiable condition for reopening. A social studies teacher insisted, “6 feet of social separation” would be “a must” for them. An ENL teacher wrote, “I don’t think I would feel safe unless social distancing were implemented,” An ELA [English Language Arts] teacher agrees, “It seems unrealistic that we will be comfortable being back in [an] overcrowded room, 35 bodies, asked to do active group work.” A Social Studies Teacher wrote, “Classrooms I have been teaching in … [are] tiny and there’s really no space between students. Also the windows don’t open making it a breeding ground with no ventilation. Work spaces in the offices are too tight as well. It’s impossible to work 6 feet apart from anybody. How can I safely plan a lesson on the computer and make copies?” An ISS teacher wrote, “the Special Education self-contained classrooms … can have up to 15 students and many paraprofessionals in a VERY EXTREMELY TINY room. This CANNOT happen when we go back to school. There is no way we can keep safe in these conditions … We would be risking their health by making this acceptable.”

Some searched for ways to make it possible: A social studies teacher called for “one way hallways, and classrooms with no more than 12 desks.” A science teacher insisted, “Group work and Danielson should be abolished. How can teachers be expected to promote collaborative work experiences in the classrooms amidst this pandemic when we must have social distancing? And class sizes must be much smaller.” An ELA teacher agreed, “We need classes to be much smaller so we can distance and we can’t have kids in clusters on top of each other … these conditions [in the UFT petition] aren’t enough.”

But some of the same people, as well as others, just didn’t think it was possible. The same ENL Teacher who said they wouldn’t feel safe without social distancing added, “I just don’t see how that can be realistically implemented given the size of my school and the maximum class size of 34. Some of the classrooms I taught in last semester, particularly those for self-contained ISS classes, are TINY and were PACKED with 15 students, 2 teachers and several paraprofessionals.” In the same vein, an ISS teacher said, “I’m afraid [social distancing] is impossible. We have a lot of students and a lot of staff. To try to separate every one with the limit of classrooms and teachers we have, I’m not too sure that we can do that.” Another social studies teacher wrote, “There is very little that can be done to fight this virus other than social distancing. How do you do that in a school of four thousand people?” “I do not believe it is possible to keep safe distance during passing in high schools,” wrote a math teacher, “How do we keep everyone 6 feet apart?” An ELA Teacher agrees, “To get kids to sit 6 feet apart you could only have, what, ten kids in the room? There is no way we could do that … ”

Pharmaceutical solutions

Although the UFT leadership never mentioned it, several respondents expressed thoughts about antiviral medications and/or vaccines. Wrote one social studies teacher, “I do know that I DON’T want to be mandated for a vaccine …” A ELA teacher wrote, “Vaccinations should never be forced on anyone to maintain a job.” On the opposite side, an ENL teacher wrote that an antiviral treatment or vaccine “would be the only thing that would make me feel totally safe.” An ISS teacher wrote, “The safest condition is for the vaccine to come out,” and a counselor also agreed, “We need a vaccine before we can all go back into one building.”

Levels of social transmission

Some chapter members brought in a factor that Mulgrew has not mentioned at all: the level of community transmission. A science teacher wrote, “It is difficult to predict what infection rates would be by September.” A paraprofessional focused on the same factor: “I don’t think we should reopen yet when they still have so many active cases out there, because the more people in a building the more cases can reappear.”

Distrust of the authorities

There was widespread skepticism that the administration could be trusted either to keep staff and students safe, or to be honest and transparent. A science teacher recalled, “The last day that students were in school, the principal came to classrooms telling students there were no Covid-19 cases she knew about in the school.” [It was later revealed there was at least one self-reported case]. They continued, “I can imagine crowded classrooms in September with so-called publicly announced safety procedures that will be largely ignored in reality.” Another science teacher wrote, “I don’t trust administration to keep promises.”

Regarding social distancing, a social studies teacher observed, “The Administration can [work in social distance] but not the teachers.” A counselor wrote, “We were promised sanitary conditions prior to [school closing], yet had no supplies in the building until a day before [closing]. We had sick people in the building, who were told to come to work and isolate.” An ISS teacher wrote, “Administration needs to be transparent with us. I believe we have been lied to about how many people were actually diagnosed with the virus before we left. How can we feel safe and trust our Administration if they lie to us?”

Keeping reopened schools safe

Clearly, a mechanism is needed that would allow any school worker to make a direct complaint about any unsafe or unhealthy condition to a neutral third party, preferably a body of public health experts, attached to neither the DOE nor the UFT staff. Why not the UFT? During the school closure, its leadership has not earned the members’ trust, either. The UFT leadership, unlike teacher unions in other large cities – such as Chicago, Los Angeles and Oakland – has not negotiated a Memo of Agreement or Understanding regarding remote learning. “I believe that the UFT should have consulted with us,” wrote a math teacher regarding the leadership’s preconditions for reopening. Worse, the leadership has shown itself unresponsive to members’ concerns, freezing the grievance process and greatly narrowing by whom, and over what issues, violations can be addressed. Thus, the union leadership has not demonstrated it can be relied upon to promptly resolve life and death issues that might arise in reopened schools. This third party should have a short time frame to correct the problem, or, ideally, the affected workers and students should have the right to refuse to work under the dangerous condition.

Looking toward the future

Some felt pessimistic and powerless: “I think that the DOE will force teachers to come back to work and most safety issues will be ignored,” wrote a science teacher, “Teachers will have to take the risk.” An ISS teacher concluded, “It would be nice to wait for an antiviral treatment … but waiting on drugs is impossible.” One math teacher could not even think about coming back, “that is four months away, plus, what can we ask?” Others sounded ready to take a strong stand: another math teacher’s view was “If we do open schools in September will all this be possible? I think not, therefore, keep schools closed until safe for all.” A counselor agrees, “We need to return when the situation is under control.” So does an ISS teacher, “We need to have high probability from the medical experts … that it is really safe to open things up again.” And a social studies teacher concludes, “I have this feeling kids won’t be back in September.”

Whenever NYC schools reopen, clearly it will be up to school workers, by direct action, to insure a safe return, just as it was left up to the same workers, by the same means, to force the government to shut down the dangerous and unhealthy schools in March.

Marian Swerdlow is a School Chapter Leader, United Federation of Teachers, retired. A version of this article appeared on the We Know What’s Up website on May 10, 2020.