Peter Solenberger

Posted May 20, 2020

Like Stephen Mahood and Promise Li, authors of Socialism from below after Bernie: Local organizing and rank-and-file militancy, I’m a member of Solidarity and the Democratic Socialists of America. I helped found Huron Valley DSA (HVDSA) and Northern Michigan DSA (NMDSA).

Most Solidarity and DSA members would agree with the article’s proposal to encourage Sanders supporters to turn from his now-ended campaign to local organizing and rank-and-file militancy. Other points in the article are subjects of debate in both Solidarity and DSA. My goal in this article is to address some of the points of debate and to draw a critical balance sheet of the campaign.

The 2020 Bernie Sanders campaign

The 2020 Sanders campaign was once again an electoral campaign in the Democratic Party. Its platform was the New Deal, the old-time religion of the party, updated to the 21st century on matters of race, gender and the environment.

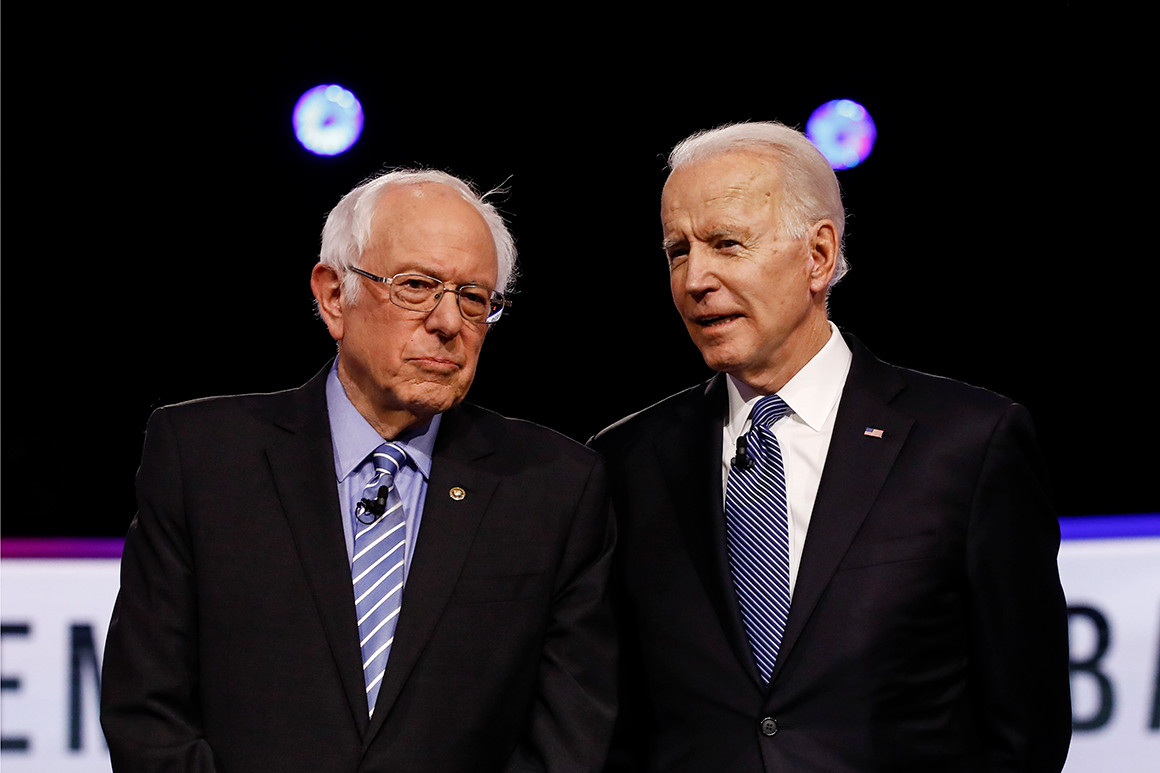

Articles in DSA publications and Jacobin describe the campaign as “socialist.” For example, the April 9 DSA leadership statement Socialism is the Best Path Forward, issued immediately after Sanders dropped out and endorsed Joe Biden, describes it as “the most successful socialist electoral campaign in U.S. history.”

But the campaign wasn’t socialist. It wasn’t anticapitalist. It wasn’t anti-imperialist. It was New Deal. On the Sanders campaign website the only reference to socialism by Sanders himself is a June 12, 2019 speech, Sanders Calls For 21st Century Bill of Rights. In it he equates his brand of socialism with the New Deal. Here’s its most developed passage:

In a famous 1936 campaign speech Roosevelt stated, “We had to struggle with the old enemies of peace — business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering.

“They had begun to consider the government of the United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs. We know now that government by organized money is just as dangerous as government by organized mob.

“Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me — and I welcome their hatred.”

Despite that opposition, by rallying the American people, FDR and his progressive coalition created the New Deal, won four terms, and created an economy that worked for all and not just the few.

Today, New Deal initiatives like Social Security, unemployment compensation, the right to form a union, the minimum wage, protection for farmers, regulation of Wall Street and massive infrastructure improvements are considered pillars of American society.

But, while he stood up for the working families of our country, we can never forget that President Roosevelt was reviled by the oligarchs of his time, who berated these extremely popular programs as “socialism.”

To his credit, Sanders never renounced the socialism of his youth. He redefined it as the New Deal, but he didn’t renounce it. This encouraged many of his supporters to go beyond the inspiring but vague slogans of the global justice movement (“Another world is possible”) and Occupy (“We are the 99%”) to speak directly of capitalism and socialism.

After forty years of Democratic Party capitulation to neoliberalism, putting the New Deal on the party’s agenda again and making socialism a topic of conversation among activists were big accomplishments. There’s no need to exaggerate. The campaign wasn’t socialist.

Us, not him

Articles in DSA publications and Jacobin confuse cause and effect in their enthusiasm for the Sanders campaign. A prominent campaign slogan was, “Not me, us.” The slogan should be inverted, viewed from the bottom up. “Us, not him” more accurately describes the dynamic.

For 25 years Sanders did his thing in Congress and got little hearing in the Democratic Party or anywhere else. In the 2016 Democratic presidential primary he caught a wave of worker and youth enthusiasm for New Deal policies. He rode the wave skillfully, but he didn’t create it.

Waves of rebellion had been rising and falling since the mid-1990s, when “There is no alternative” began to give way to “Another world is possible” among activists.

Some of its pre-2016 highlights in the U.S. were the 1997 UPS strike, the 1999 Battle of Seattle, the 2000-2002 global justice movement, the huge rallies against the 2003 Iraq war, the 2004 March for Women’s Lives, the 2005 Katrina solidarity, the 2006 marches and strikes for immigrant rights, rejection of austerity during the 2007-09 Great Recession, Barack Obama’s 2008 election, the Dreamers, Wisconsin 2011, Occupy 2011, the 2012 Chicago teachers’ strike, the 2013-14 Black Lives Matter movement, the 2014 calling out of campus rape, the campaign for same-sex marriage culminating in the 2015 Supreme Court decision, and Fight for Fifteen.

The rebellious sentiment found an electoral expression in the 2016 Sanders campaign. To the surprise of almost everyone, including Sanders, his campaign attracted tens of thousands of activists and millions of voters, transforming it from a marginal protest into a challenge to the Democratic Party establishment.

The 2020 Sanders campaign was a reprise of 2016. Not as inspiring, because it wasn’t new and its more clear-eyed supporters knew it would end with Sanders defeated, endorsing the establishment candidate. But it showed that support for New Deal politics had become endemic in the ranks of the Democratic Party.

Articles in DSA publications and Jacobin credit the 2016 Sanders campaign with resurrecting DSA. Again, more credit should go to ranks, the youth and workers who flooded into DSA. Many of them had campaigned for Sanders, and some joined during the campaign. But more were inspired to join by the defeat of the campaign and then the election of Donald Trump. If the campaign had won, they’d have joined the Democratic Party, not DSA.

Again this year, the Sander campaign and, even more, its defeat seem to be leading to an influx of new DSA members.

The Democratic Party

Historically, DSA and its predecessor organizations have located themselves in the left wing of the Democratic Party. Historically, Solidarity has refused to locate there. Here’s a passage from the 1986 Solidarity Founding Statement.

The necessity for autonomous class action is at the root of our conception of independent political action. Class independence is at the heart of revolutionary socialist working-class politics, which emphasizes workers’ self-organization, self-activity and reliance on their own strength — including building their own alliances with the oppressed. In the electoral arena, the principle of working-class self-organization requires an independent party.

Lacking such a party, the working class and other progressive movements are reduced to pressure groups on bourgeois politics, no matter how militant their activity. This is the trap from which labor in the U.S. has yet to escape.

Just as we believe that workers, through their class institutions (the unions) should have a policy of challenging the employers rather than of accepting collaboration, we believe the same principle should apply in the arena of politics. Unlike reformists, we do not see ourselves as “critics” of the bourgeois parties, the Democratic and Republican parties, but as opponents. Indeed, in the U.S. the question of the Democratic Party is the most important principled and practical divide between the politics of reformism and revolutionary socialism…

In fact, the Democratic Party is the graveyard of movements for social and political change. It is a party controlled by and thoroughly tied to corporate capital, and for that reason is irrevocably committed to the maintenance of the world U.S. economic empire…

No matter how often the quest to capture the Democratic Party for progressive politics fails — as it always does and always will — the argument for “giving it another try” constantly revives in the wake of each defeat…

It is therefore essential that socialists continue to make the case for an independent party based on the labor movement.

The specific form of DSA’s current attempt to “give it another try” is to support left candidates running in Democratic Party primaries and, if they’re nominated, running as Democrats in the general election. Some in DSA still seek to reform the Democratic Party. Others see the party as just a “ballot line” that they can use.

The Sanders experience shows why the 1986 Solidarity position remains correct. The point isn’t to criticize Sanders. He’s a New Deal Democrat. His strategy flowed from his politics:

- Run as a Democrat, because that’s the only way to get millions of votes.

- Play by the Democratic Party rules, because that’s the only way to run as a Democrat.

- Play nicely, because that’s the only way to be listened to.

- Support the Democratic nominee, because that’s the only way to beat Trump.

- Within that framework, campaign as well as possible.

With a higher level of class struggle, Sanders might have won. The ruling class might have decided that they had to make concessions to the working class to contain the upsurge, as they did with Roosevelt and the original New Deal. But not with the current level of class struggle.

Sanders is out, but the wheel is still in spin with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) and Rashida Tlaib, the two open DSA members in Congress. AOC won her 2018 Democratic Party primary because she faced a self-satisfied, lazy, white male opponent who misjudged the voters. Tlaib won hers because the Black community and Democratic Party establishment failed to narrow the field to a single candidate to represent them.

AOC and Tlaib face a dilemma. If they cause too much trouble, the Democratic Party machine will primary them out, as it did Cynthia McKinney, first in 2002 and then definitively in 2006. If they don’t cause trouble, why are they there?

Under such pressure, not surprisingly, they’ve voted upwards of 95% with their party, including on bills to approve the imperial budget. They’ve proposed few measures of their own, and the few they’ve proposed have gone nowhere. In particular, AOC’s February 2019 resolution “Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal” generated public discussion but went nowhere.

The two-party system

The Democratic Party can’t be understood in isolation. It’s a component of the two-party system. It works together with the Republican Party to make sure that the government does only what a consensus of the ruling class wants. This is true, whatever self-conception its politicians may have.

The two parties are funded by large donors and circumscribed by the media. Their politicians pass through the revolving door between government and business, including NGOs. The less scrupulous enrich themselves, and nearly all prosper.

The two parties agree on the fundamentals of capitalist property, state power and empire. That’s why the military budget passes almost unanimously every time. But they’re not exactly the same. Historically, the Democrats have presented themselves as more caring, while the Republicans have presented themselves as more realistic.

Half the voting-age population generally doesn’t vote, seeing no point to it. The other half is divided between Democrats and Republicans, with somewhat more Democrats than Republicans. Workers, women, people of color, and youth tend to vote Democratic, if they vote at all. The affluent, men, whites and older folk tend to vote Republican.

The levels of support for the two parties are close enough to lead to an alternation between them at the federal level. The Democrats win, fail to deliver, disappoint their base, and energize the Republicans. The Republicans win, fail to deliver, disappoint their base, and energize the Democrats. In the post-World War II period the presidential alternation has been Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy/Johnson, Nixon/Ford, Carter, Reagan/Bush I, Clinton, Bush II, Obama, Trump.

The base might not like the party’s candidate, but they’re herded to the polls to vote for the lesser evil. This year, Democrats are told, “If you don’t vote for Biden, you’ll get Trump.” Republicans are told, “If you don’t vote for Trump, you’ll get Biden.”

The capitalists prefer a situation of divided power like the present one, in which the Republicans have the presidency and a majority in the Senate, and the Democrats have a majority in the House. Most politicians of both parties prefer divided power too, whatever their protestations, so they can blame each other for the gridlock.

The outcome isn’t always gridlock. The military budget always passes. Wars are approved. In the past six weeks the federal government has allocated nearly $3 trillion to prevent economic and social collapse. The legislation included assistance to workers, but only what the ruling class thought was necessary.

At the state and local level the two-party system may not involve an alternation of administrations, but the party machines, donors, media, and “lesser evil” manipulation — plus the requirement that states and municipalities balance their budgets — limit what even the best-intentioned elected officials can do.

In 2020 the two-party system has worked quite well. A majority of Democratic Party voters favor New Deal measures, but a majority still voted for neoliberal Biden as best able to beat Trump. Forty percent wanted Sanders, but most of them will vote for Biden as the lesser evil.

DSA probably won’t endorse Biden, since it’s bound by a 2019 convention resolution made back in the heady days when many DSAers thought Sanders might win. But most DSAers, especially in “battleground states,” will probably vote for Biden as the lesser evil to Trump.

Even Solidarity is divided, with some members favoring the Green Party and our comrade Howie Hawkins, some planning to hold their noses and vote for Biden, and some wanting to forget the whole mess.

Class struggle and electoral politics

In the 1990s Labor Party Advocates (LPA) had a great slogan, “The bosses have two parties. We need at least one.” LPA attempted to launch a Labor Party in 1996. The party had backing from several leftwing unions, many movement activists, and most of the socialist left.

The AFL-CIO leadership tolerated the Labor Party on one condition: The party would not run candidates against Democrats. Not running candidates made the Labor Party ineffective and superfluous. It held another convention in 1998 and expired.

The Labor Party was a good idea whose time had not yet come. The recovery of working-class consciousness and activity had just begun. The class struggle was still at a very low level. If the Labor Party had decided to run candidates against Democrats — impossible with its governing structure — the unions would have left, and the party would have collapsed by a different route. The Labor Party was damned if it did, and damned if it didn’t.

DSA is in a somewhat similar situation today. The class struggle and working-class consciousness are not at a high enough level to allow DSA to split the Democratic Party and build a mass alternative. It could only take steps in that direction. But which steps?

Most DSA members see the need for a working-class party independent of the Democrats. But few are ready to make the break. They see winning office as “power” and running as a Democrat as the way to win office. They want to use the Democratic Party ballot line to get elected and carry out their own policies.

That’s not how the game works. To run as a Democrat you have to follow the rules of the party. You have to support whoever wins nomination. If you’re elected, you have to work with your colleagues. Hence, Sanders endorses Biden, and Sanders, AOC and Tlaib mostly vote with their party.

An alternative is the third-party route, that of the Greens. The Greens have a program much superior to that of Bernie Sanders, on a par with DSA. The Greens are explicitly ecosocialist and anticapitalist. Sanders proposes reforming capitalism. The Greens propose doing away with it.

By running a presidential candidate, the Greens popularize their ideas far more than they could if they held back. They keep ballot status in many states by running statewide candidates who lose but get large numbers of votes doing so. For example, a socialist who wants to run for office in Michigan can do it as a Green, no problem, at least for now.

The price of running as a Green, rather than as a Democrat, is that you’re unlikely to win above the local level, and often not even there. Green campaigns are mostly educational campaigns. Green votes are mostly protest votes.

Another alternative is to run as an independent. Kshama Sawant in Seattle and Rossana Rodríguez-Sanchez in Chicago show that at the local level it’s possible to win as an independent. But these victories are exceptional and bring no real power. Again, they’re mainly educational.

The Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA) showed that it’s possible to run a slate of independent candidates and win. The 2013 election of Chokwe Lumumba as mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, was more complicated. He ran as a Democrat but described himself as a Mississippi Freedom Democrat. He had the backing of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement and community organizations, which gave his campaign exceptional independence.

The Richmond and Jackson efforts made some important gains and then fractured under the pressures of governing, the Jackson effort after the premature death of Lumumba in 2014.

Where to go from here

With the current level of class struggle, electoral activity can have only limited and ambiguous success. It’s great that Sanders did as well as he did in the Democratic Party presidential primaries. I hope that Biden beats Trump in November. But Sanders’s success and Biden’s, if he succeeds, strengthen the Democratic Party and reinforce the two-party system.

That’s not a reason to deny the advantage of their success or to wish for their failure. But it is a reason to consider whether electoral campaigns in the Democratic Party are what revolutionary socialists should be doing.

I agree with the 1986 Solidarity view, held by many other revolutionary socialists, that we should try to relate positively to the ranks of progressive Democratic Party campaigns. We should sympathize with their aims and acknowledge the superiority of their candidate’s platform and practice.

We should say that we’d support the candidate running as an independent, but not running as a Democrat. We should explain that our principal concern is to promote working-class political independence, and supporting a Democrat, even a Jesse Jackson or a Bernie Sanders, would undercut that goal.

That leaves plenty of space for supporting socialists and other leftists running as Greens or independents. Revolutionary socialists should do so where we can. But we should understand that electoral campaigns are mainly educational at this point, auxiliary to class struggle. They’re not power.

The way forward is to raise the level of class struggle, beginning with local organizing and rank-and-file militancy. Draw lessons about the Democratic Party and the two-party system from the Sanders experience, and then move on.