Dianne Feeley

Posted July 30, 2019

Why does the once-powerful United Auto Workers keep losing?

That question is on many lips after the union’s sad organizing defeat at Volkswagen in Tennessee; its unfolding corruption scandal; and its toothless response to the news that General Motors will close five plants.

The symbolism was clear last January when, instead of joining a spirited coalition demonstration at the International Auto Show, the UAW held a candlelight vigil nearby.

While the auto show demonstrators called on the city to take back the Detroit-Hamtramck plant—the land was given to GM 37 years before—and convert it to green production, speakers at the union vigil threatened only to file grievances and use “all legal means” to reverse the plant closings.

BECAME MANAGEMENT’S PARTNER

Since the late 1970s, UAW leaders have sold concessions as necessary given the economic crisis. They claimed that as times got better, we could win back what we had given up.

But while times did get better for the corporations, workers have only been forced to take more concessions, resulting in a much weaker union. (See Labor Notes’ 1983 book Concessions and How to Beat Them by Jane Slaughter.)

Ever since the 1980s, when the UAW accepted management’s “team concept,” workers are supposed to aid management in efficiently running production—even if that results in deteriorating working conditions and job elimination.

The UAW leadership views itself as management’s partner, responsible for boosting the company’s productivity and keeping members in line. Locals vie with each other to keep their plants open, even at the expense of other UAW members. (See Labor Notes’ 1988 book Choosing Sides: Unions and the Team Concept by Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter. It outlined this process and how to fight against it.)

Management has continued to restructure. By the 1990s, UAW leaders went along with the Big Three in selling off a number of parts plants. Eventually those remaining UAW locals accepted weaker contracts. Tiered wages and benefits were first introduced in the auto industry through the parts plants.

With the 2008-2009 economic crisis, the tiers spread to GM, Chrysler, and Ford. In the case of the federal bailout of GM and Chrysler, the leadership went along with the government’s demand that workers needed to sacrifice if taxpayers were to “save” the company. So the UAW’s acceptance of tiers was negotiated in order to save jobs. And of course Ford, which didn’t go through bankruptcy, claimed it needed concessions as well.

In a newspaper op-ed, President Gary Jones emphasized that 2019 contract negotiations were about to begin. It sounded like the UAW was ready to offer concessions in order to cajole GM into reversing the closings. (Negotiations for a new contract with the Big Three began this week—see box.)

A local union bulletin to members mostly detailed the opportunities to transfer to other plants. UAW leaders brag about these transfer rights, although the available jobs may be more than 100 miles from home.

But not all members are guaranteed even this much. Transfer rights are weaker or nonexistent for contract workers such as janitors or material handlers, or those designated “temporaries,” no matter how long they have been working.

This is a union that was once the pacesetter for American labor, establishing cost-of-living raises, health insurance, and health and safety provisions. It has militant roots and one of the most democratic union constitutions. Compared to many other unions, its top leaders’ salaries are modest; a skilled worker with overtime can match them. So what went wrong?

CAN’T FIGHT CITY HALL

The answer lies in the long history of the union’s ruling party, the Administration Caucus. For decades the AC has fought any grassroots attempts to fight management or democratize the union.

It maintains that workers owe their jobs to the corporation. Fighting to improve working conditions is off-limits because it could imperil the company’s bottom line.

At the same time, the caucus has provided a lucrative career path for a few. At the Detroit plant that’s scheduled to close in January 2020, local union officials were quick to squelch even the suggestion of a fightback committee. Are they hoping their loyalty will be rewarded with jobs on the union’s regional or international staff? Or do they really believe the top leaders can magically negotiate a concessions-free contract this time around?

UNACCOUNTABLE LEADERS

The Administration Caucus, once known as the Reuther Caucus, has controlled the top UAW leadership positions since the late 1940s. Originally it was one of a number of contending caucuses. But over time, it consolidated its dominance.

By the late 1940s and early 1950s the caucus denounced, marginalized, and expelled communists and other leftists. It also blocked the advancement of African American leaders until it came face to face with a Black insurgency in the early 1970s. Then it co-opted those Black workers willing to join its caucus.

Big Three Talks Begin

Bargaining for the new contract between the Auto Workers (UAW) and the Big Three automakers opened this week.

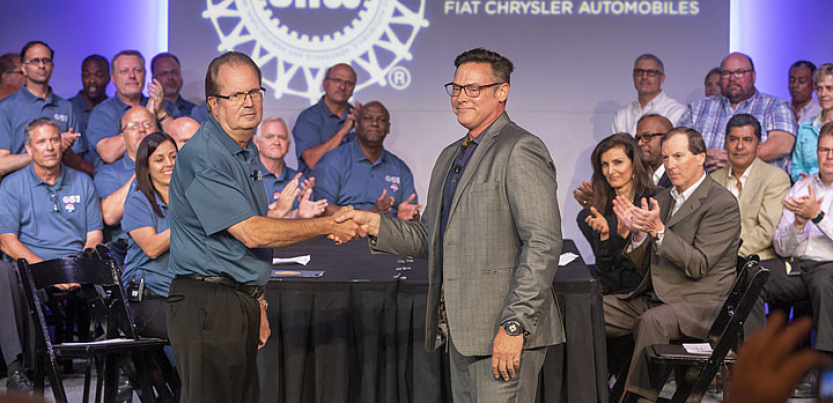

To kick off negotiations, UAW officials shook hands with the Ford negotiating team on July 15, and with the GM and FCA teams the following day. Outside, 150 auto workers protested the closure of their GM plants. Leaders of Local 1112 in Lordstown, Ohio, organized the demonstration.

The next step is for the UAW to announce which of the Big Three will be this year’s target. The UAW-Big Three contract may be seen as a “pattern” for the industry. But in reality it is three separate, although similar, contracts. There are also many separate, and generally inferior, contracts in the parts industry.

The tradition of targeting one of the Big Three has been justified by the UAW as choosing the most profitable corporation in order to negotiate the best possible contract, then forcing the others to accept the pattern. Although that strategy hasn’t proven effective in years, this is how the Administration Caucus proceeds.

By August the first draft contract will be discussed and voted on; the other two will be ready shortly afterward. Since the UAW tradition is not to work without a contract, these three should be signed, sealed, and delivered in early September.

SURPRISE VOTE-NO LAST TIME

For the 2015 contract, to the surprise of most auto workers, UAW officials targeted Fiat-Chrysler (FCA), the weakest of the three. At that time the second tier made up almost 40 percent of the workforce in some plants.

UAW officials had announced this would be the contract that would end two-tier wages. When that didn’t occur, FCA workers angrily voted it down, forcing top UAW officials, who had negotiated and supported the deal, back to the table.

Testimony around the corruption of the FCA training fund later revealed that the officials were off celebrating the contract’s passage in a fancy downtown restaurant, and were shocked by the vote.

In the end the revised contracts barely passed, and only because the UAW leaders claimed they had negotiated a bridge between the tiers. Strangely enough, it’s an eight-year bridge in a four-year contract. And the bridge is only for wages; not for upgrading benefits. The agreement also carved out several new tiers that most workers didn’t spot.

TIERS PERSIST

This time around, FCA, having completed its round of restructuring, is expanding production. GM has already laid off thousands and closed four U.S. plants, including two assembly plants. Ford signaled it will begin that process a little further down the road.

Most auto workers and retirees see the priority as making temporary workers permanent, putting an end to tiers, restoring pensions and—given the profitability of the corporations—restoring cost-of-living allowances (COLA).

“Traditional” long-term employees, second-tier workers hired since 2007, and “temps” all work side by side. Sometimes the lower tier workers do even harder jobs.

Until a decade ago, the UAW culture was based on equality. So the reality that long-term workers can afford to go to doctors and dentists while others put off going is like a cancerous growth.

Workers see how those hired since the economic crisis, particularly the temps, are bullied by management. And in many cases workers in the different strata are relatives. This inequality has created antagonisms within what should be a united workforce.

—Dianne Feeley

Today most UAW members are only dimly aware that the leadership replicates itself by an AC that incorporates almost all newly elected officials.

The AC controls the union’s headquarters (Solidarity House), its regional offices, its organizers, its communication and education networks, and its power to appoint people to a variety of jobs off the line. It nominates one of its members to run for every union office, and provides material aid to win. At conventions, it invites delegates to attend its meetings and then binds them to the positions taken.

As an efficient jobs program, the caucus replenishes itself. This year more than 90 percent of the delegates to the union’s Bargaining Convention were members.

NEW DIRECTIONS MOVEMENT

The last broad opposition caucus in the UAW was New Directions. It developed in the late 1980s out of opposition to the concessions that UAW officials were promoting. Jerry Tucker, then Region 5 assistant director, maintained that concessions were unnecessary if workers were prepared to use their power.

He showed local leaders how to organize workers to work without producing—what he called “running the plant backwards.” This required ingenuity from workers and backup from officials. It worked—but instead of embracing this strategy, Solidarity House saw this as a threat to their rule.

When local officials supported Tucker’s run for Region 5 director in 1986, the Administration Caucus stole the election. Tucker contested it and won a federally mandated re-vote two years later. But by then there wasn’t much left of his three-year term.

UAW leaders considered Tucker a traitor. They installed an assistant director to undermine his plans and report to Solidarity House. A weekly newsletter mocking and attacking Tucker was distributed throughout the region.

In the next election UAW leaders used their power to defeat Tucker, along with Donny Douglas, a New Directions leader running for director in Region 1.

Opposition from a united leadership eventually swept away New Directions. Some of its leaders, like Douglas, were incorporated back into their caucus and given jobs at Solidarity House.

BRIBES AND CORRUPTION

The recent scandal of high-level officials taking bribes from Chrysler (now FCA) management has exposed a reality that most people wouldn’t have believed. Was a culture of corruption the payoff for negotiating contracts that significantly reduced labor costs?

Keith Mickens, once a militant, became the first UAW official sentenced. He was given a year in jail and slapped with a $10,000 fine. In minimizing his role, he maintained that he accepted the funds for personal use “out of intense pressure by his superiors, not malice or greed.”

Had Mickens failed to follow orders from his boss Vice President General Holiefield, who has since died, he would have been forced to relinquish his job and go back to the line. His statement that he feared going back into the plant was a slap in the face of every auto worker and showed the disdain that caucus leaders have for those of us “dumb enough” not to get ourselves better jobs.

The Detroit News revealed how former President Dennis Williams used interest from the strike and defense fund to have the union build for him a luxurious three-bedroom “cabin” fronting at the UAW conference center on Black Lake. Although no federal charges have been brought against him, a top aide told prosecutors that Williams encouraged UAW officials to save the union money by inappropriately charging various travel and entertainment expenses to the training fund’s tab.

At last year’s UAW Constitutional Convention, Williams, then the outgoing president, attributed the corruption to “a few bad apples.” He argued that none of the money came from union sources, but rather from jointly operated Fiat Chrysler training center funds. Actually these funds are partly financed by workers—for every hour of overtime an individual works, five cents of the wage is apportioned to the fund. The fund is to benefit workers by offering advanced training. If the funds aren’t there, training can’t occur.

BRING IN THE TEMPS

Opposition to the high-handed Administrative Caucus continues to appear. Websites pop up and a few dissidents even win local office or convention delegate seats.

Autoworker Caravan, one of a handful of networks of active and retired workers, was organized during the 2008-2009 economic crisis. We hold monthly conference calls, organize demonstrations and conferences, write and circulate UAW convention resolutions, and build solidarity with auto workers in other countries.

While UAW officials only printed up the “highlights” of the national contract, AWC continued the tradition of New Directions in demanding the actual contract language. We would circulate the draft contract and produce a leaflet outlining its “lowlights.”

Not until Bob King’s presidency did the union begin to post the contracts for each corporation to the UAW website. Should the current president fail to continue this tradition, we could resume distribution along with our analysis of the lowlights.

WHAT’S NEEDED NOW

UAW officials say they want GM’s Lordstown and Detroit-Hamtramck assembly plants to remain open. Yet they did not even match the demonstrations and meetings that the Canadian union Unifor organized against the threatened closure of GM’s assembly plant in Oshawa, Ontario. Nor did they respond to Unifor’s efforts to develop a unified strategy against the common employer.

Industry analysts note that despite the Big Three’s profitability over the last several years, there will be a slowing pace of sales along with a transition to electric vehicles that use fewer parts. But UAW officials plow ahead with the expectation that they can win contracts that the membership will ratify. Unlike 2015, they do not promise an end the extensive use of temps and tiers. Nor have they prepared the membership for a strike.

In the face of this massive restructuring of the industry, the AC has not developed innovative proposals that could capture the imaginations of members and of the whole country.

While the companies have developed work schedules that condemn some crews to permanent weekend work at regular pay, the AC remained silent. It could have looked in the UAW toolbox and come up with the slogan of “30 hours work for 40 hours pay.” But there hasn’t been serious talk of reducing the work week in the UAW since before the 1979-81 recession.

GM’S CEO Mary Barra talks about wanting GM to be known as a transportation corporation, not an auto company. But even that doesn’t seem to have jarred the AC into re-examining its model of negotiations. If several plants are to be shut in order to finance research and development for this new stage, why doesn’t the UAW assert that the Big Three must assume financial responsibility? The transition should not be on the backs of workers. If the corporations are unable to do so, the government should declare eminent domain and take over the plants.

HUGE TRANSITION NEEDED

At the beginning of World War II, auto production was suspended and plants were converted to war production within six months. Today we’re facing the even larger crisis of climate change.

Instead of being locked into a destructive fossil fuel economy, auto workers and engineers have the knowledge and ingenuity to develop an alternative and efficient mass transit system. Many cities are already moving to buying electric buses.

It’s a crime that the UAW’s Administration Caucus has become so corrupt and unable to think strategically that it is an obstacle to members using the power and know-how we possess to be the engine for a Green New Deal.

But given the crisis, perhaps we can use the example of teachers who recently struck even where striking was supposedly “illegal.” The teachers had to push reluctant union officials into action. But they did—and they started the process of democratizing their union as they won some of their demands.

Auto workers can use this negotiating period to be organizing on the job, preparing to vote down an inadequate contract and to strike. Such a perspective can open up the possibility of taking back the union. Having transformed ourselves, the UAW would be able to develop in-plant committees in the South and be capable of going up against the propaganda of the corporations and their front-men politicians.

Dianne Feeley is a retired auto worker active with Autoworker Caravan, a rank-and-file group that grew out of opposition to the concessions imposed during the 2008-2009 economic crisis.

This was originally published in Labor Notes on July 19, 2019.