Bureau of the Fourth International

Posted June 13, 2019

Even if the European Union has managed to contain the banking crisis for the moment and maintains an annual growth rate of 2%, this has been achieved at the cost of maintaining a high overall debt level of 86%, which serves as a basis for structural adjustment plans in several countries. These policies, which attack social protection systems and labour regulations, have further widened the gap in wages and living conditions across the Union for the working classes. Many countries in the South and East of the EU have seen a real exodus of their youth over the past 10 years.

At the same time, the EU, while blocking access for emigrants from Africa and the Middle East, causing more than 17,000 deaths in the Mediterranean over the past five years, continues to exercise its neocolonial policy towards African populations, in particular through the control of the European Central Bank with the African Financial Community (CFA) franc and the African-Caribbean-Pacific (ACP-EU) agreements. At the same time, in the face of the social exasperation caused by this situation, regimes have linked their ultra-neoliberal reforms and a strong state, restricting democratic rights and strengthening security laws, using the terrorist threat or the control of migrants as a pretext.

In this context, the results of the recent European elections reflected several aspects of the political situation in the European Union.

In general, they show a process of political fragmentation in which the extreme right seems to have made the most progress.

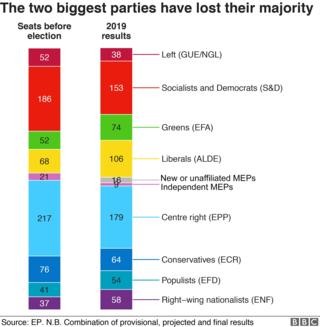

The traditional dominant parties, which are part of the European People´s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), have suffered a major setback, showing the increasing mistrust of European citizens to these traditional parties. This decline is only partly compensated by the rise of new pro-EU centre-liberal parties in the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), such as Ciudadanos, the British Lib Dems and, in France, the Macron En Marche movement.

The Green parties have had an important increase, obtaining their most seats ever. This reflects partly an increasing environmentalist consciousness across Europe, also shown in the discourses of some mainstream parties. The recent social movements across Europe, in particular of youth against climate change, with the importance of Fridays4Future mobilizations, show that this is becoming more and more a central political issue. However, unfortunately, the response of most Green parties to this trend is to direct the changing consciousness to policies of management within the neoliberal policies and institutions, the German Greens being the most clear example.

The parties to the left, grouped in the European United Left–Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL), have suffered a major setback, going from 52 members to 38 and becoming the last group of the chamber.

The general trend is to a strengthening of the most reactionary parties. The far right directly gains 78 seats and, above all, polarizes all rightwing groups, both conservative and nationalist.

The far right, led by Italy´s Matteo Salvini and France´s Marine Le Pen, is now on the rise in Europe. Without challenging the power of the large capitalist groups responsible for social injustice, precariousness and the abandonment of social protection systems, it has been able to adapt its discourse on European issues. From a policy of exiting the EU and the Euro they have decided to try to conquer it from within, building alliances across the continent and provoking the European institutions to appear as challengers to the EU order. They are limiting their programme above all to two issues, which they consider to be priorities: migration flows and security issues. On these themes, by pushing to the end the logic already implemented by the leaders of the EU and most national governments, it seeks to divert the exasperation of the working classes produced by austerity policies towards a racist, nationalist and Islamophobic expression.

In government in several European countries in recent years (in Italy, Austria, Slovakia and Bulgaria in particular), despite its demagogic statements, it is obviously adapting itself to ultra-neoliberal policies. Moreover, the traditional right is easily accommodated, coexisting with Poland’s Law and Justice Party in the case of the British Conservatives, with Hungary’s Viktor Orbán in the case of the EPP, and with Spain’s Vox in the case of the EPP-affiliated People´s Party and ALDE-affiliated Ciudadanos. Today, there is indeed an “orbanization” of the European right. This is also true for “liberal” parties such as France’s En Marche, which, while presenting itself as a barrier against the extreme right, are themselves implementing an ultra-neoliberal policy, coupled with a frontal challenge to democratic rights and increased police violence. Its ally in the Spanish State, Ciudadanos has chosen to become an openly rightwing party, willing to establish agreements with far-right Vox in order to build rightwing majorities.

The crisis of the parties to the left of Social Democracy points to several phenomena. In 2014, during the last European elections, after several years of massive mobilization of the Greek people against the dictates of the EU, Syriza affirmed a policy of rejecting austerity. Similarly, Podemos had just formed in the wake of 15M [the mobilizations which began on May 15, 2011] and the Mareas [the “tides” popular assemblies], major social movements, and stated that it wanted to affirm, on the left, a policy of breaking with social-democratic management. Around these two experiences, in Europe, tens of thousands of activists hoped to find a political response to their struggles, to mobilizations for social, democratic and environmental emergencies, to the rejection of discrimination and gender-based and homophobic violence, to the reception of migrants in the face of racist policies.

Syriza´s surrender succeeded in deeply shaking this hope. The Podemos experience has been shaken by internal disputes, given its inability to establish a proper inner democratic functioning able to maintain unity, and the Pablo Iglesias leadership has increasingly taken the line to become a subordinated ally to the Socialist Party. Jean-Luc Mélenchon´s France Insoumise has also chosen to give itself a functioning model based on charismatic leadership, and has been unable to attract the great discontent expressed in the Gilet Jaunes movement. Overall, the credibility and usefulness of the radical left has not kept pace with the powerful social movements of recent years.

On the other hand, it is necessary to note the electoral success, especially of the Left Bloc (Bloco) and of the Workers Party of Belgium (PTB), which were able to advance their political position in these elections.

The Brexit disaster has stressed the necessity of advancing a project to challenge the European Union that goes hand in hand with the interests of the working classes.

The 2016 referendum, called in an attempt to heal the longstanding pro-Europe vs pro-US rift in the ruling Tory party, has led to three years of chaos and crisis as the government has failed to negotiate an agreement. The period since the 2016 referendum campaign has been characterized by a carnival of reaction with increased media and physical attacks on those perceived from to be migrants, i.e. from Black, Muslim, Middle Eastern or Eastern European communities. Nigel Farage’s new Brexit Party, its sole platform being for a “hard” or “no deal” Brexit, won the European elections. Labour’s support declined, both the “remain” and “leave” camps, and it was overtaken in the European elections by the clearly “remain” Liberal Democrats. After one extension, Britain is set to leave on October 31 — almost certainly with no deal — and it is likely that only a general election and/or a second referendum can stop that.

The challenge for the radical left is to be credible and useful in the field of mobilizations and standing, in campaigns and elections, for political requirements in response to social, democratic and ecological emergencies. The task is not easy: while the far right moulds itself into the capitalist system to develop its xenophobic and reactionary themes, the radical left, like the social movements on which it relies, clashes head-on with the system in putting forward its political demands. It is against it that the political attacks of the ruling class and the media, whose editorial line it controls, are really carried out. The other great pending task of the moment is to be able to build mass organizations that combine a democratic and militant structure with the ability to address themselves to the broad masses. Here we have to learn both from the successes and failures of the recent years.

But the dynamism of international mobilizations against violence against women and discrimination, those taking place throughout Europe for the climate, the depth of mobilizations such as the yellow jackets in France, must stimulate us as to the urgency of building political mobilizations in Europe capable of pushing these social demands, to build political movements linking them to a social emancipation project, directly facing capitalist exploitation and oppression.

This statement appeared on the International Viewpoint website on June 9, 2019 here.