Posted October 15, 2007

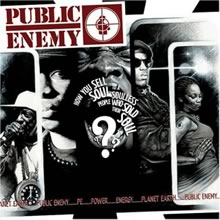

So, when I first heard plans for this Solidarity blog at our 2006 convention, I wanted to do a review of New Whirl Order (2005) and Rebirth of a Nation (2006,) and compare them to Flavor of Love. Since then, How You Sell Soul to a Soulless People who Sold Their Soul? (2007) has been released. Flavor of Love had a second season, and spinoffs I Love New York and Charmed School gained widespread attention.

I have learned that “Rebel without a Pause” is part of the soundtrack to Grand Theft Auto: Sand Andreas, an addictive video game widely noted for racial stereotyping (the player’s character is a Black man and the objective is committing brutal crimes).

I wrote the review in Fall 2006, but “my computer ate it”…really. However, most of my thesis is much better conveyed in a blog entry entitled The Political Significance of the Flavor of Love.

I was motivated to write this blog (and to post the link to Jenifer’s blog above) because Public Enemy once spoke to me. Their lyrics prodded me to do more than listen and love music. Sometimes they still do. A few years ago, Solidarity bought copies of their single Make Love, F*ck War (2004 “power to the people, ’cause the people want peace.”) and played it at anti-war events.

But since 1991 Public Enemy has continued a decline from a chart topping political hip hop group to obscurity. No album since the 1998 soundtrack to Spike Lee’s He Got Game has even hit the Billboard charts. They can still occasionally drop a track that will rekindle fire in the heart of a revolutionary. But their tired lyrics and mediocre beats don’t speak to the youth.

Flavor of Love: turn off that bullshit!

Capitalism makes a fool of our heroes. Once proof that a hip hop act could drop science without selling out, Public Enemy is now content to preach to the already converted thought their internet releases and college radio play. In turn, we all- Chuck, Flav, you, me, the movements- suffer from their self-imposed isolation. Media corporations have enormous power. The industry that Chuck D decided to take on “turn off the radio…turn off that bullshit”… “burn Hollywood, burn!” have power over placement and distribution and even music reviews. Meanwhile, Flava Flav drank the Kool Aid and has moved from the hype man of a leading force for social change to a leading minstrel in the television world of failed human relationships.

Later this year, Public Enemy- together with Louis Armstrong and Count Basie will be inducted into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame. Oh, did I say they were also admitting Mariah Carey?

Comments

4 responses to “Public Enemy off the Charts”

The Roots are now Jimmy Fallon’s house band. Public Enemy guests:

This just shows the illusions of many on the left who think that hip-hop is automatically progressive. PE were always suspect; even at their most “political”, they played cartoonish superhero outlaws while the passive masses cheered from the sideline. “Flava of Love” is not so much a betrayal as an extension of this fundamental elitism and market orientation.

I agree, it is depressing to see the trajectory of Public Enemy. Luckily there are some great young artists out there making very political, and great, music. Check out, for example:

Outernational

http://www.outernational.net/

and Debajo Del Agua

http://www.myspace.com/debajodelagua

I agree about the sad state of Public Enemy. There might be a more positive spin to take on it, though. The hip-hop world has moved on in style since Public Enemy’s day, and there are new hip-hop artists who offer useful political perspectives, if not as often or as overtly as Public Enemy. Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and Common (and maybe I’m even a little outdated here) often combine productive political critiques with great music. That said, of course, these artists are by no means politically “pure”–they sell their images and songs to advertisers, for instance. I wonder, however, whether political “purity” is a fair thing to ask of our musicians and artists. Maybe we should embrace their useful artistic creations as tools for good political work and accept that the artists themselves don’t always live up to our ideals.