A review by Martin Oppenheimer

Posted January 31, 2019

Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia

By Peter Cole

University of Illinois Press, 2007, 227 pages.

A century ago the Industrial Workers of the World controlled the Philadelphia waterfront. The rise and fall of Local 8 of the IWW, a predominantly Black but integrated union, is the subject of Peter Cole’s gripping Wobblies on the Waterfront. He follows this remarkable union from its total shutdown of the waterfront in a 1913 strike to its demise in 1922. Weakened by years-long government repression, its end came after a bitter strike in 1922. It could not survive internal disputes, an employer lockout and scabs from the competing International Longshoremen’s Association. The return of the shape-up system of work assignments (depicted in On the Waterfront starring Marlon Brando) to displace the IWW’s hiring hall then ended equal employment rights for African-American waterfront workers.

Working conditions in the early 1900s were abysmal. Before the IWW came along, the shape-up was compared to a “slave market” (14). The labor was “brutal” and there were many injuries and deaths. Safety rules were unknown. The work was irregular and pre-union wages at U.S. ports were barely subsistence.

Housing was wretched. In South Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward, where many Black dock workers lived, W.E.B. DuBois described the conditions in his famous study The Philadelphia Negro. On top of that, the politicians of Philadelphia were among the most corrupt in the nation, as the muckraker Lincoln Steffens made clear in his report “Philadelphia, Corrupt and Contented.” The police were in the pockets of the employing class, whether in shipping or any other industry, and regularly arrested and beat strikers while protecting scabs.

Dock work was the third most common source of employment for Black men in the Seventh Ward, exceeded only by domestic and hotel jobs. African-Americans “were excluded completely from most of the city’s workplaces, notably the city’s many industrial plants…” (22). But on the waterfront the need for workers was too large to exclude Black men, and despite the efforts of other ethnicities, especially the Irish, to keep them out, shipping employers hired Blacks. Employers used inter-racial hostilities to keep workers divided and longshore unions out.

Initial efforts to organize the New York and Philadelphia waterfronts were initiated by an organizer from England’s Dockers’ Union. The idea was to assure that New York and Philadelphia longshoremen would not load ships during English dock strikes. The new American Longshoremen’s Union quickly enrolled 15,000 men in New York. The Philadelphia Local, with some 1,500 men, struck on June 1, 1898 for wage increases and more safety measures and quickly won most of their demands. However, a financial scandal in the New York Local resulted in the collapse of the ALU only a month later.

The Philadelphia Wobblies first organized Hungarian metal workers, then a range of other occupations such as bakers, railroad workers, some textile workers, and even button makers, consolidated into a single Local 57 since there were insufficient numbers for separate units. The IWW had been targeting many kinds of workers on the East Coast by then, but until 1913 had not found a foothold on the Philadelphia docks. The Wobblies did not go out to find longshoremen to organize; rather, as Cole puts it, “the longshoremen found the IWW” (40). The Wobblies were conducting a strike at a sugar refinery when a group of longshoremen approached the strike organizer, who quickly helped them formulated a set of demands. On May 14, 1913, some 1,500 longshoremen closed down the port. Most of them had joined the IWW, and Local 8 was chartered a few days later. Fourteen days later the city’s shippers gave in to most of the strikers’ demands, including the novel idea of negotiating with a multi-ethnic, inter-racial union committee. The strike “ushered in a decade of Wobbly power on the Philadelphia waterfront” (49) despite having to fight off numerous attempts by the ILA (abetted by the shipping employers) to raid and destroy Local 8.

The Great War in Europe was a bonanza for the shipping industry. In May 1916, on the third anniversary of Local 8’s founding, “three thousand longshoremen withheld their labor to honor themselves” without repercussions (68). The Local now included 3,500 longshoremen, 160 sailors (mostly coal shovelers) and the harbor boatmen. Port employers went along with demands for higher wages except for the Southern Steamship Company, which was soon struck. The Company hired strikebreakers and “special officers” to guard their piers. Black and white union men battled replacements, which included Black strikebreakers but even as segregation was increasing in the city, the union’s interracial bonds held. Thousands of strikers and strikebreakers fought in the streets. There were shootings and several men were killed. Mounted police charged strikers and soon “the district looked as if martial law had been imposed” (71). Although the strike petered out, the Local continued to grow. However, when the U.S. entered the war, Local 8 and the IWW faced an entirely new situation.

On September 5, 1917, IWW halls and offices across the country were raided by the U.S. Justice Department. Local 8 and its allied Marine Transport Workers’ offices were raided and masses of documents were seized as evidence of sedition. The IWW’s Textile Workers Industrial Union’s offices on Allegheny Avenue in Northeast Philadelphia were raided by police. Six Philadelphia Wobblies including one African-American were among 166 nationwide (Big Bill Haywood included) arrested for interfering with the Draft and violating the Espionage Act. In August 1918, after a Chicago trial lasting four months, the 101 who had been indicted were all found guilty, based entirely on pre-war written materials which of course reflected the IWW’s militantly anti-capitalist and anti-war position. Two of the Philadelphians received twenty-year sentences, the other four ten years each. “The purpose of the raids and arrests was abundantly clear…to destroy the IWW” despite the fact that their members “loyally loaded thousands of vessels…” (88). The rank-and-file of Local 8 supported the war effort, hundreds serving in the military, which seems contrary to the IWW’s position on the war. No work stoppages took place after May 1917, and ironically the U.S. Navy did not allow explosives to be loaded in Philadelphia unless by Local 8 longshoremen. ILA members were not trusted due to a record of accidents.

The war was only the opening salvo in an all-out campaign by “corporate America and many in the government to suppress the labor movement via the Open Shop and Red Scare” (91). A series of anarchist bombings (including two in Philadelphia), the fear of bolshevism, and a strike wave beginning on January 1, 1919, with the Seattle General Strike whipped up a nativist hysteria begun during the war. This culminated in the Justice Department’s infamous “Palmer Raids” that began on November 7, 1919. Employer groups now decided to put an end to labor unions by stepping up an “Americanism” campaign “equating patriotism with the open shop and socialism with being un-American” (105).

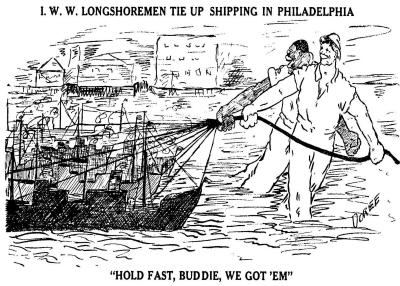

IWW Local 8, with an inexperienced new leadership replacing their imprisoned comrades, faced a growing employer offensive coordinated by the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce. The workers demanded higher wages to cope with inflation and a drop in the work week to forty-four hours. The companies refused. The strike that began on May 26, 1920, ”was the largest the port of Philadelphia had ever seen, with close to 9,000 workers out (and) more than 150 ships immediately…idled” (111). But the union could not sustain the strike and after six weeks called it off.

Government repression certainly weakened Philadelphia’s IWW, but Cole insists there were two additional elements in its downfall. “The brutal infighting among pro- and anti-Soviet Wobblies (and) the debate over centralization…whipsawed Local 8 and the entire IWW.” (129). This conflict lasted from August 1920 to November 1921 (chapter 7). In August 1920 the Chicago-based IWW General Executive Board expelled Local 8 for allegedly loading arms intended for General Pyotr Wrangel’s counter-revolutionary “white” forces in Russia. Some Wobblies believed at the time that Communist sympathizers within the IWW “cooked up” the arms story when they realized that they could not “capture” Local 8. Ben Fletcher, the African-American IWW leader, is quoted as saying the Communists engaged in a “Liquidating Program upon orders from Moscow” (136).

By August 1920, the conflict between the rising Communists and the declining IWW was intense. The Comintern’s official policy had changed from a “dual union” approach similar to that of the IWW to a policy of boring from within the AFL. This came after Lenin’s famous attack on sectarianism, “Left-Wing” Communism, An Infantile Disorder (May 1920). Effectively this meant supporting the ILA. The conflict over the Soviet Union spilled over into a battle between Local 8 and the GEB over initiation fees, which pitted local against GEB policies. Despite these problems, neither the Garveyites nor the ILA were able to split Local 8 to create breakaway locals, although these attempts did force Local 8 to compromise in order to be readmitted to the national IWW.

The inflation following the war forced the marine industry unions to call major strikes “only to see their organizations torn asunder by ferocious employer counteroffensives, often with federal aid” (148). Increasing numbers of African-Americans emigrating from the South swelled the ranks of the unemployed, meaning there were thousands more workers for employers to try to recruit as strikebreakers. In October 1922 a cabal of shipping employers determined to break the IWW’s hold on the Philadelphia waterfront. It was decided to cease dealings with Local 8 and lock their members out in order to prevent them from working. On October 27 the members of Local 8 voted to strike. 5,000 longshoremen were now out and thirty ships stood idle. Substitutes were soon available including from ILA members from New York. The U.S. government’s Shipping Board fully supported the employers, even supplying a ship to house the scabs. Within ten days the strike had collapsed.

Cole’s narrative stops at this point. There were still more splits to come, and by the mid-1950s the IWW was scarcely more than a sect. But did the IWW perhaps help lay the groundwork for the direct action CIO strikes of the 1930s? Cole doesn’t say. It would have also been useful if Cole had carried his story forward to the present because the IWW has survived and is engaged in organizing efforts among service workers, as at some Starbucks outlets. But apparently it has no presence in the “blue collar” industrial world or on the waterfront. Today the much diminished competing ILA has a tenuous hold on Philadelphia shipping, battling other unions and employers using non-union labor. Moving shipping from ILA-controlled terminals to non-ILA facilities has been a recent anti-ILA strategy.

The IWW was able to hold on to the Philadelphia waterfront so long as inter-racial solidarity held. It was committed to rank-and-file union democracy, as opposed to the top-down, actually dictatorial structure of the ILA. But during the 1922 strike it was unable to compete with massive numbers of strike-breakers These included Black workers, many of them illiterate, who were fleeing the South’s economic decline and racist practices.

The question is whether even the most militant and democratic union with a sterling record of inter-racial solidarity could have coped with forces far beyond its control. Even if Local 8 had survived the 1920’s, the Depression would have weakened it further. Following the Second World War and the onset of the Cold War, the anti-communist hysteria would have caught the IWW in its coils. It was listed on the infamous Attorney General’s 1950 List of Subversive Organizations even though it barely existed as an organization by then. Finally, the containerization process in shipping decimated employment on the waterfront. This book is a powerful reminder of what a militant and democratic union can accomplish, but also serves as a warning that only a far more powerful labor movement than we have at present can avoid the kind of tragedy depicted here.

Martin Oppenheimer is professor emeritus of sociology, Rutgers University, where he was a grievance counselor for the AAUP-AFT. He is a member of Central N.J. Democratic Socialists of America.