Ron Lare

October 18, 2018

Readers following events in Germany may have seen the alarming news that in late August the far right took over the streets of Chemnitz in two days of racist, anti-immigrant actions. There is video of fascists in Chemnitz openly chasing down and beating immigrants. A police official said the cops regained their presence in Chemnitz streets only behind social-democratic mobilizations. More than 65,000 people attended an anti-racist rock concert in Chemnitz on September 3 protesting against the far right and neo-Nazi activities, but the trauma of the event remained.

Berlin demonstration

The news since has been better. On Saturday, October 13, the day before elections in Bavaria, 240,000 demonstrated in Berlin for diversity and against racism, xenophobia and other bigotry. Although the whole left participated, the rally did not have a militant overall character. Yet it was taken everywhere as a huge, vigorous and hopeful protest against the growing far right in Germany. In a change from Chemnitz, progressives dominated the streets.

Bavarian election

On Sunday, October 14, Bavaria held elections. Bavaria is Germany’s largest state by area and second largest by population and economy. It is relatively prosperous and in German terms tends to be conservative. The election results upset this image.

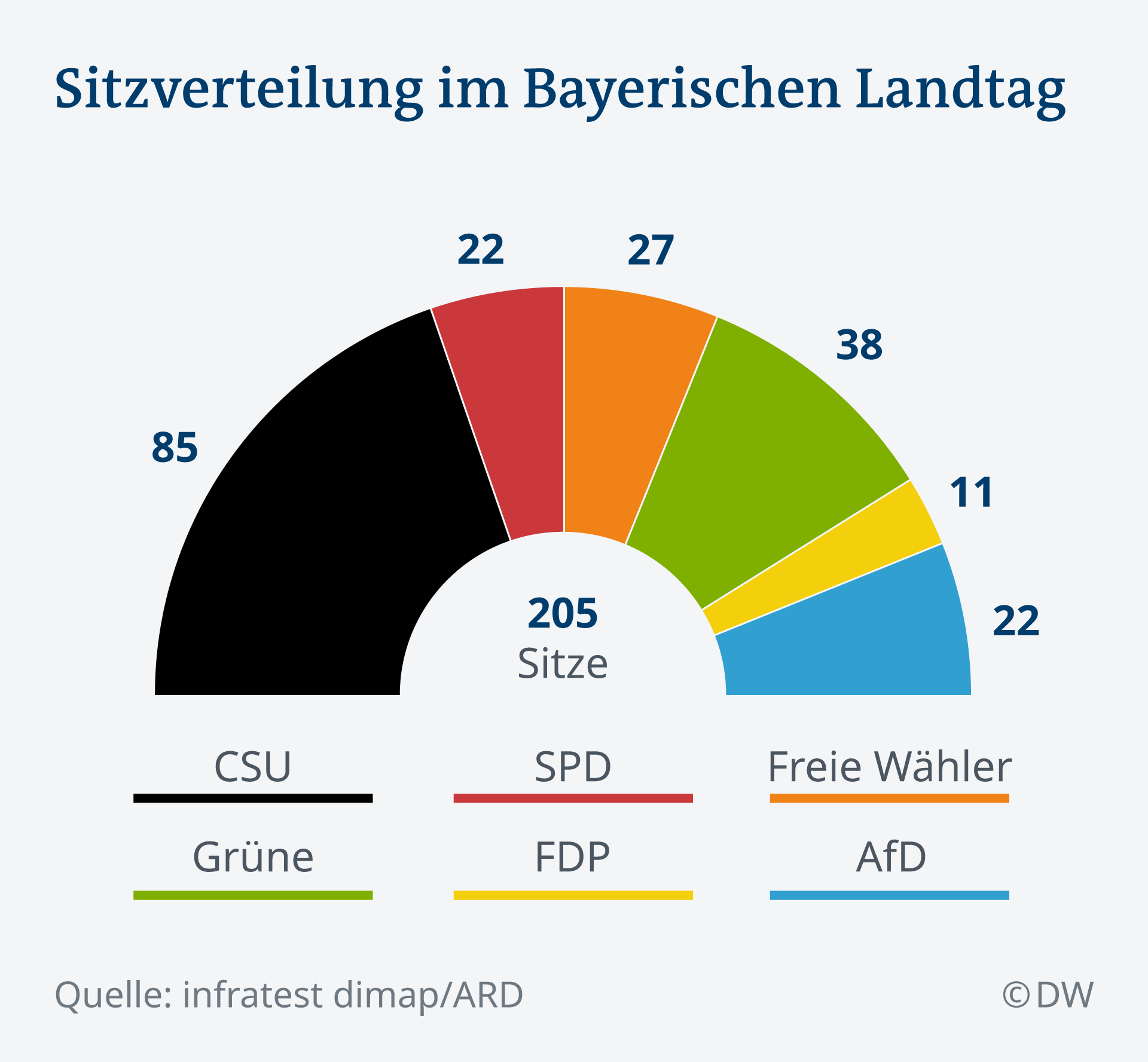

Those who gained big in Sunday’s Bavarian elections were the Greens and the far right Alternative for Germany (AfD). The AfD ran for the first time in Bavaria, receiving more than 10% of the vote. A spokeswoman said they are now “anchored and rooted in southern Germany” as elsewhere. However, the AfD did not do as well as many feared and finished behind the Greens and even the peculiar “Free Voters.”

US media wrongly seem to talk only about the very real and dangerous growth of the AfD, not about the Greens’ advance. Here are the results by party, with the change since the last Bavarian election:

| Party | Vote (%) | Change | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSU | 37.2 | -10.4 | Part of Merkel-CDU’s national center-right government |

| Greens | 17.5 | +8.9 | Perhaps party best known in US, aspires to govern |

| Free Voters | 11.6 | +2.6 | Pragmatic populists, not necessarily right wing |

| AfD | 10.2 | 10.2 | Far right with a Nazi wing; their 1st Bavarian election |

| SPD | 9.7 | -20.9 | Social Democrats, in CDU-CSU-SPD national government |

| FDP | 5.1 | +1.8 | Pro-business liberals |

| Die Linke | 3.2 | +1.1 | Far left among well-known parties, some FI members |

| Other | 5.1 | +3.3 |

For the first time, the CSU, the Bavarian sister party of Merkel’s national CDU (Christian Democrats), cannot rule in Bavaria without partners.

Why the shift?

Polls said Bavarians’ top issues were the environment, affordable housing and education, with only a third seeing immigration as a major concern.

The homegrown Bavarian Christian conservatives, the CSU, seem to have blown their majority by assuming that Bavarian voters would go for a Trump-ist campaign, allowing them to remain in the increasingly unpopular national coalition government with Merkel’s CDU and the SPD. Instead of the CSU, most voters who are rabid against immigration went for the real thing. That is, the far right AfD with its more virulent stance on immigration, including a Nazi wing (and its right-wing version of an appeal to working-class economic concerns).

But the other big choice of CSU defectors were the Greens. Polls indicate that the CSU lost more of its votes to the Greens than to the AfD, not what most expected. Why? If housing and education were so important in the exit and earlier polls, why did the social-democrats, the SPD, do so poorly? Voters likely thought the Greens were at least as good as SPD on these issues, better on the environment, and more trustworthy.

The SPD on the soft left, like the CSU center-rightists, suffers from being in a sputtering national coalition with Merkel’s CDU. 86% of former SPD voters agreed with the statement that the SPD “need to renew themselves in opposition in Berlin.” This is essentially what the SPD youth have long demanded and threatened to split over, and is now echoed more across SPD generations.

Among votes for all but one of the parties, women and men divided about equally, with women slightly more likely to vote for a left than a right party. But the AfD vote was different. 13% of men but only 7% of women voted for the far-right AfD. In some ways the leading spokesperson for the AfD is Alice Weidel, who seeks to give the AfD some progressive cover by noting that she is herself a lesbian single mom. She worked for Goldman Sachs and speaks Mandarin after working for years on China. But the AfD is a mainly a far-right white men’s club.

The proportion of women in the German parliament is not as great as one might think seeing CDU (Merkel), SPD (Nahles), Die Linke (Wagenknecht), somewhat the Greens, and the AfD feature women as top party leaders. As for CSU and FDP, woman leaders of theirs are seldom, if ever, featured in national TV coverage.

The Free Voters are an association with a grab bag of what they see as pragmatic positions. They are somewhat populist but seem not part of general European right-wing populism. The FDP is a pro-business liberal party. The media mention these two and the Greens as potential CSU partners in a new Bavarian government. As of today, the CSU prefers the Free Voters.

Having come in second in the election, would the Greens reject or accept a Bavarian governing partnership with CSU? The left of the SPD thinks that their party’s partnerships were political suicide. But the Greens may want to be in regional or national government badly enough to take the risk.

Die Linke and Aufstehen

This summer, Die Linke forces around Sahra Wagenknecht and Oskar LaFontaine initiated a movement, not a party, called Aufstehen (“Stand Up” or “Arise”). This draws in members of Die Linke but also of SPD and Greens as well as independents. For now, this leaves ambiguous Aufstehen’s relationship to Die Linke as a party. Does Aufstehen mean to renew Die Linke, recruit from SPD and Green youth and other youth not oriented to parties, start a new party, and/or stay a non-party movement? Do they aim at a place in a government?

Does Aufstehen fit the pattern of broad left party initiatives around Europe and the world? On the question of parties, Wagenknecht has said that if there were a party led by a Jeremy Corbyn in Germany, that would be worth following, but there is not one right now, given the state of the SPD and the small size of Die Linke.

What Aufstehen has to say about immigration is controversial on the left. A mainstream German news source says, “The movement could present a leftist case for limiting migration.” That essentially means Aufstehen wants to find a left compromise over against the far left and radical progressive demand for open borders.

Some on the left contend that open borders are impossible under capitalism. They conclude that if the left does not soon have a solution that can win workers’ majority support, a right-wing solution by the Trumps and Marine LePens will soon be in place and block a longer-term left solution.

Many on the far left see such proposals as a concession to rightwing populism in an attempt to win over workers such as those attracted to the AfD, Trump, etc. In reply, many radical youth, revolutionaries, and even some left and religious liberals, consider such a compromise on immigration unacceptable on principle and a dangerous opening to the right.

In parliament, Die Linke seems implicitly to aspire to be part of a minority in a government led by the SPD and Greens. For now, Die Linke does not have close to the electoral weight for that.

In the 1970s, supporters of the British IS in Germany founded a Trotskyist organization called Linksruck — left shift or turn. Hopeful leftists now use this word as a common noun without referring to that organization. They see Germany as turning to the left generally, as indicated by progressive mobilizations against fascism and to protect immigrants (including Mediterranean Sea rescues) and the environment.

A left turn is unlikely to be based on Die Linke or Aufstehen. However, to whatever extent there may be a left surge, the question of broad parties and entering capitalist governments arises.

On a lighter note

To end on a lighter note, the Süddeutsche Zeitung (South German Newspaper) has the largest circulation of any German paper. Its leftish views lead some wags to say the newspaper itself is the real opposition “party” in Bavaria.

When the right ranted about Bavaria being on the geographic front lines of a dark immigrant influx, the newspaper began a report denouncing the great mass of rowdy outsider lowlifes about to invade Bavaria, undermining culture, committing crimes and getting drunk…by which the newspaper went on to say they meant white ethnic Germans about to arrive in Bavaria to carouse at Oktoberfest.

The political situation in Germany is in some ways alarming. But most Germans reject fascism, and the Berlin mobilization and the Bavarian election show the possibility of a favorable outcome.

Comments

One response to “Better news from Germany

Berlin mobilization, Bavarian election”

Yes, Germany needs a linksruck!!