Bill Smaldone

October 2, 2018

Donald Trump’s election has emboldened white nationalist groups and armed militias who are entering public space in ways almost unprecedented in the years since the civil rights movement. In debates on the left about how to respond to this upsurge and, in particular, about the tactics we should use, Antifascist organizers often reference Germany during Hitler’s rise. They argue that Hitler, like Trump, began as a buffoon and that the early Nazis were a relatively small force, like the militias and white supremacists today. BUT because liberals did not take them seriously and failed to immediately and forcefully confront the early manifestations of fascism, they allowed the Nazis to grow. Learning the lessons of this history, they say, we should never ignore the mobilizations of the far right, using every means, including physical confrontation, to drive them out of public space and obliterate them as a political presence.

We thought it would be useful to explore the rise of Hitler with someone who has studied this in depth.

Bill Smaldone teaches History at Willamette University; his specialty is Germany in the 20th century. He is author, among other books, of Confronting Hitler (Lexington Books, 2009) and European Socialism: A Concise History (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014). Bill served four years as a radical on the Salem, Oregon, City Council. He also cofounded Radio KMUZ, a community radio station in Salem, and he’s on the editorial board of the Salem Weekly, an alternative paper.

In this interview, he outlines the conditions that permitted the Nazis to take power, including the nature of the German state and the German economy, the dilemmas and conflicts of the left, and the development of Nazi strategy and action. We conclude by briefly drawing the lessons of this history and their application to a left anti-fascist strategy, recognizing both the unsettling and ominous similarities of the contemporary U.S. to Weimar Germany and also the many profound differences between these two societies.

Part I: Defeat, Mutiny, Revolution, Republic—Germany 1918-1919

Soliwebzine: Let’s set the stage for the story by describing Germany in 1918–the moment of its defeat in World War I.

Bill Smaldone: In the fall of 1918, the German General Staff, recognizing that the Austrian armies had collapsed, their own military was losing, there were food shortages, casualties had been enormous and people were war weary, decided to end the war.

Although the military had effectively been running the country since 1914, they preferred not to negotiate a peace and suggested that the Kaiser give power over to a government that was answerable to the Reichstag, to the Parliament. Although there had been a Parliament for a long time, the Chancellor (the German equivalent of Prime Minister) was not responsible to the Parliament and could simply override Parliamentary decisions whenever it wished. So, this was a kind of revolution from above, carried out by the military, basically, in order to force the civilians to carry out the surrender.

In October 1918 the Kaiser appointed a liberal aristocrat, Prince Max, as Chancellor and Max then formed a cabinet with members of a number of bourgeois parties and the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the leading socialist party. This cabinet began to carry out parliamentary reforms and convert Germany into a true parliamentary republic, again with all of this being done now from above.

Meanwhile, the Kaiser undertook negotiations with the western powers who decided that they really didn’t want to negotiate with the German government until the Kaiser had abdicated. So, there was this sort of long month in which they were trying to get negotiations going. The German Officer Corps were unhappy with this news and this was particularly true in the Navy. Although Germany had built up an enormous fleet to challenge the British Navy, the German fleet only fought one major engagement with the British, in 1916. Germany was unable to break the British blockade and for the most part all of the surface ships sat in port during the war.

The Naval High Command decided that they were going to fight one more glorious battle and go down with all guns blazing. And they ordered the ships in the port of Kiel to steam up and get ready to fight it out with the British fleet in the North Sea.

The sailors on the ships thought otherwise, and decided they didn’t want to go down in a blaze of glory. They had already had tremendous tension with their officers, because conditions for rank and file sailors were terrible in the German Navy during the war. All of this basically fueled a mutiny that exploded in Kiel when armed sailors seized control of first the naval base and then the city.

They then took off from Northern Germany and traveled around the country calling on domestic garrisons to overthrow the established government. And so you had widespread, large-scale uprisings in most German cities in the first week or two of November.

On November 9th, the Kaiser abdicated and Prince Max handed over power to a new chancellor, Friedrich Ebert, who was a Social Democrat. The next day, Ebert invited Hugo Haase and the leadership of the Independent Social Democratic Party, a left-wing antiwar party, to join in a socialist coalition government. And this was the basis then of the new provisional government that would run the country for the next two months.

Soliwebzine: The Workers’ Councils were really running the cities. These were radically democratic organizations. For many of us on the left, this moment is an inspiring example of working-class self-organization

Bill: Workers and soldiers established a new revolutionary government and that revolutionary government was based in two institutions. One institution was the revolutionary Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils and the other institution was the provisional government, made up of the two existing socialist parties, the Socialist Party and the Independent Socialist Party. And what eventually transpires is that the councils transfer power to the provisional government and you have the emergence of a socialist provisional government in the fall of 1918, that laid the ground for the establishment of the German Republic in August of 1919.

In December of 1918, delegates from the workers’ councils met in The First Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies where they created an Executive Council that was elected to carry out the wishes of the Congress of Councils between congresses.

And what’s interesting here is you have a moment that on the surface appears to be similar to a period of dual power in Russia in 1917, where you had the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies and you also had the provisional government. So, for a moment, you have a kind of dual power system in Germany in the fall of 1918. The difference is that in December at the First Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils, the German councils essentially voted to give the lion’s share of authority to the provisional government under their supervision and then they voted to allow elections for January of 1919 which would be followed by a constituent assembly that would meet in February to write a new constitution and create a parliamentary government.

So, that meeting in December is a key moment, because the councils effectively handed their authority over to the provisional government. The members of the provisional government, especially Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the Social Democratic Party, wanted a parliamentary system. They did not want a council system. They associated the councils with the Bolsheviks. They didn’t want a Bolshevik-style revolution to come to Germany. They wanted a parliamentary system.

Soliwebzine: The councils mobilized workers and soldiers who were armed, yet they decided to cede their power.

Bill: Actually, there were variations across cities, but in most places, the councils held power briefly and they were mainly concerned with making sure that order was maintained in each locality. In very few cities did they really unseat completely the local authorities, that is, the local city councils and so forth. Often there was a great deal of communication back and forth between the different groups.

So, in most areas, in a short time, the authority of local city institutions was restored, and the councils gradually faded away. There were some important exceptions to this, but from January until the spring of 1919, the councils were definitely in retreat. They didn’t have the ability, the infrastructure, the resources to form effective governments that could compete with the long-time entrenched local authorities. And in fact, most of them didn’t want to take power away from these authorities.

And that’s really a key thing to understand. The reason the Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in effect handed power over to the provisional government in December 1918 was that most of the people elected to that body were Social Democrats. They followed what the party had been telling them for the last 40 years and that is: once we have power, we’re going to have a parliamentary system with proportional representation; we will win a majority and with that majority, we will build socialism.

Nobody had really been thinking about a system like a workers’ council system until very recently. Prior to the First World War, very few socialists had thought about what the socialist future would look like. No one had really talked about councils as bodies of socialist power in the prewar period. This is a creation really of the revolutions of 1917 in Russia. And that soviet model met with a mixed response, at best, when it was transferred into central and western Europe. You had some workers in the labor movement who were inspired by it and you had the majority of workers in the labor movement who were not or had mixed feelings about it.

Soliwebzine: What was the role of revolutionaries in the councils? Were there anarchists? Revolutionary socialists?

Bill: Those were very small organizations, and many of their leaders emerged as important figures for a short time in 1918, but they didn’t have staying power. Once you started having elections, once you began to draw the broader masses into political processes, very few of the radical groups were able to sustain themselves in power.

It’s very similar to the revolutions in France in the 18th and 19th centuries, where the revolutions began in Paris; Paris was the focal point of revolutionary activity. That’s where the population was most radical. And then as soon as the revolution spread to the rest of France, very conservative forces were able to bring power to bear, because in effect, revolutionary Paris was not revolutionary France.

The same was true in Germany, where in big cities like Berlin, Hamburg, or Munich, there was a lot of revolutionary activity. Those places were not the whole country and once the whole country was drawn into the process, it got much more conservative in terms of the general outlook.

Part II: The Weimar Republic: Social Democrats in Power, Contested from the right and the left, 1919-1923

Soliwebzine: And the Social Democrats, of course, had a party in the parliament before that and even though they supported the war, they remained sort of the opposition with a country-wide reach, whereas communists or anarchists were much smaller.

Bill: That’s right. In 1914, the Social Democrats betrayed their internationalist principles and voted to support Germany’s war effort. But, unlike the socialist parties in England and France, they did not enter the government. German elites were uninterested in really sharing power with the Social Democrats and did not allow the Social Democrats to join a governing wartime coalition. And so, during the war, even though the Social Democratic majority leadership remained loyal to the government and supported the war, they were less implicated in the politics of the regime than the other political parties.

As the war unfolded, a big anti-war opposition developed within the Social Democratic party. The result was a split in 1917, when the opposition broke away to form the Independent Social Democratic Party, which then pushed an openly antiwar policy. And when the new provisional government was formed in November, 1918, it was a purely socialist entity, in which the Social Democrats, headed by Friedrich Ebert, had three seats and the Independents, headed by Hugo Haase, also had three seats. While the two parties had parity within the new government, the Social Democrats had a much larger parliamentary delegation and far more members. They also retained control of the traditional infrastructure that they had built up over 40 years. The Independents initially lacked numbers, and they did not have a deeply established organizational infrastructure.

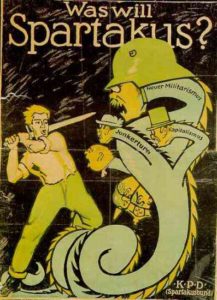

Further, the Independent Social Democrats were themselves divided. The far left, headed by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, was organized as the Spartacus League—a group organizing within the Independents to adopt more radical positions, far beyond opposition to the war. Two months after the provisional government was formed, the Independents split as the left wing broke away to form the German Communist Party (KPD), which was a very small group.

Now, suddenly, in January of 1919, you had three left parties: the Social Democrats, the Independent Social Democrats, which were not very large, but shared power with the Social Democrats, and the Communists. So, you had a fracturing of left forces.

The degree to which these parties had power could be measured by the election to the National Assembly in January of 1919. The Social Democrats got 37%; the Independent Social Democrats got 7%; the Communists refused to participate. Thus, the socialist parties had a 45% plurality, but they did not have an absolute majority, which forced them to form a coalition with some of the moderate bourgeois parties, such as the Democratic Party and the Catholic Party, in order to write a constitution.

So, given this balance of forces, you were not going to have a purely socialist constitution. In fact, you’re going to have at best a liberal constitution. So, when the National Assembly was elected, there was a debate on the left about what kind of a republic do we want. The Social Democrats in the main wanted to have a parliamentary republic in which they thought they could win a majority and bring about legislation that would transform the country along socialist lines.

The Independents were divided. You had many in the Independent Social Democratic party who wanted to have a strong council element. They wanted the councils to be somehow written into the constitution. And then, of course, you had the Communists, who wanted to have a purely Soviet-style republic. They wanted to get rid of parliament and simply have workers’ councils.

The Constitution of 1919 created the framework for a welfare state. It allowed for proportional representation, which had been a basic social democratic demand for a half a century, and in the minds of most social democrats, it opened the door to the reformist road to socialism. And so that was an impressive achievement.

The problem was the republic had few of the resources necessary to actually implement substantive reforms, while, at the same time, many of the legislative innovations that they did carry out were challenged by capital, which remained intact.

And you also have a growing right wing that consists of monarchist forces, people who wanted the return of the Kaiser or were looking for some other kind of authoritarian model, are completely opposed to the republic’s existence, and want to roll back any changes that the social democratic constitution brings about that empowers workers.

They organized new paramilitary units and underground organizations and began to launch attacks on the left. Over the course of the first three or four years of the republic’s existence, hundreds of republican officials, union leaders, and left leaders were gunned down by right wing radicals.

Soliwebzine: The Social Democrats also faced external enemies.

Yes. While the new constitution was being written, the country was still essentially under siege, because they were in process of negotiating with the Allies. The Versailles Treaty was not signed until June of 1919. So, from November 1918 until the Treaty is signed, Germany was subject to a blockade and that meant that food was not coming in; fuel was not coming in; raw material was not coming in; manufacturing broke down; the distribution of food broke down; you had widespread malnutrition, starvation in some places. The German economic situation was quite catastrophic.

Meanwhile, the Allies were demanding that Germany demobilize an army of 10 million men, very difficult thing to do under the best of circumstances, and you had millions of people, wounded soldiers and their families, killed soldiers and their families, who needed to be taken care of. These were enormous challenges.

The new government was very concerned with the maintenance of order, with getting production up and running, with just basically providing the nuts and bolts of life for people. The Social Democrats felt that if they expropriated private property, if they challenged the capitalists on their home ground, then this would have invited a foreign invasion and also a civil war. So, the Social Democrats stopped short of challenging property which they believed would precipitate an Allied invasion. (Although Germany lost the war, only the western regions around the Rhine River remained occupied.)

Soliwebzine: And the new government is challenged from the Left which is not reconciled to the Social Democrats’ vision of a bourgeois parliamentary regime.

Bill: Yes. In January 1919, there was an uprising in Berlin led by the Spartacus League (now the Communist Party) and radical allies, such as revolutionary shop stewards, which attempted to overthrow the bourgeois republic in favor of a soviet-type government. That was pretty quickly crushed on the orders of the Provisional Government—which by this time was completely controlled by the Social Democratic Party, because the Independent Socialists, furious at the SPD’s refusal to carry out radical reforms and its willingness to use force against the workers, had resigned from the government in late December.

Indeed, when the Provisional Government was formed, Friedrich Ebert, leader of the Social Democrats, had gone behind the back of his coalition partners and cut a deal with the Army Officer Corps. Basically, he said, we will leave you intact if you protect our interests against the radical left. And the army was happy to do that.

Friedrich Ebert and the leadership of the Social Democratic party were petrified of the Bolshevization of the revolution and were willing to mobilize whatever forces were necessary, including right wing ones, to defeat what they perceived, wrongly, I think, as a communist threat. I think that they overestimated the strength of the communists. They threw in their lot with reactionary forces who recognized that for the moment, it was in their interest to ally themselves with the Social Democrats to defeat the radical left. These reactionary forces calculated that the Social Democrats could be dealt with later, which did eventually happen under Hitler. The Social Democrats thought they would be able to keep the forces of the right in check, and then use the institutions of the republic to accomplish their progressive aims. And that’s where they miscalculated.

This left a lot of anti-republican elements in the government even after things settled down. So, the Weimar Republic was never really in the clear—it remained threatened by groups just waiting for a chance to restore the old order.

Soliwebzine: these groups included not just monarchists and traditional conservatives but also new right wing forces, including Hitler’s group, who are emerging in the wake of the military defeat and the economic collapse.

Bill: Yes, there were many far right forces of varied strength and Hitler’s group, which began in Bavaria in 1919, in Munich, was very small. And even when it started to grow, it remained largely a regional phenomenon, limited really to Bavaria. On the other hand, other authoritarian right-wing forces had a national reach. These were largely oriented around military officers, such as ex-general Ludendorff, who became one of the national heroes of the far right. In March of 1920, there was an attempted coup in Berlin, carried out by a group of officers who put a former official named Kapp into power. This was the so-called Kapp Putsch. For a few days it appeared that Germany was going to have a military dictatorship.

But, the government retreated from Berlin, went to the countryside and called a general strike. This call was widely followed, including by most government officials. The Putsch leaders were essentially paralyzed and their effort collapsed after just a few days.

Soliwebzine: In addition to the hardships imposed by the allies, the German economy was in quite a bit of trouble

Bill: The period immediately following the end of the war was one of economic hardship but also, in response, it was one of growing working-class militancy. The social democratic trade union movement won the eight-hour day, the right to collectively bargain, and the right to form works’ councils in most large enterprises.

However, beginning in 1922, inflation began a disastrous rise, peaking in 1923. In 1919, the value of the German mark compared to the dollar had been nine to one; by 1923 the value of the mark had fallen to 4.2 trillion German marks to the dollar. This caused extreme hardship—the value of savings was wiped out, wages did not keep up so the cost of living skyrocketed for people, and so forth. As inflation damaged the economy and unemployment rose, labor militancy also weakened. At the same time, labor’s radical wing grew stronger in the crisis.

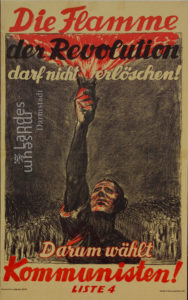

The German Communist Party (KPD), initially a sect, became a mass party in 1920 when, in keeping with the instructions of the Moscow-based Communist International (the Comintern), left-wing forces within the social democratic parties across Europe split off to form communist parties. In Germany the Comintern supporters succeeded in splitting the Independent Socialist Party, which by then had grown to 900,000 members and was poised to overtake the SPD in terms of total size. Two-thirds of the membership left the party, with most joining the KPD, transforming it overnight into a mass party. In 1923, the KPD had entered into coalition governments with the left-wing of the SPD in the states of Saxony and Thuringia where they began setting up armed units.

The far right also grew in the crisis, including Hitler’s group who carried out his so-called “beer-hall” putsch in Bavaria in 1923.

In August, 1923, the Social Democrats agreed to enter into a coalition government with several of the bourgeois parties. They, however, would not lead the new government, but would be a part of the coalition. The country would be led by Gustav Stresemann of the business oriented German People’s Party and Stresemann demanded from Friedrich Ebert, who was now the President, that he be given emergency powers allowed by the constitution in times of crisis. Essentially that gave him the ability to rule with minimal parliamentary consent and to use government decrees to mobilize the army to go into these places that were threatening the Weimar central government and unseat them.

And so, the left governments in Saxony and Thuringia, were deposed and replaced.

Meanwhile, the forces with whom Hitler tried to ally, which were the more traditional conservative forces, were really uninterested in following him and turned their guns against him. In Bavaria, when Hitler tried to seize power, he was defeated, but not by the left; he was defeated by conservative forces on the right who used local police forces to crush his putsch.

Soliwebzine: In the 1918 uprising, garrison troops led the mutiny and joined the workers’ councils. What happened to those left elements in the military?

Bill: Sailors and garrison troops may have precipitated the revolution, but they were soon swamped by millions of frontline soldiers who flooded back into Germany after the armistice. The vast majority of these troops were not revolutionary and their officers were largely horrified by the revolution. After the military was demobilized, only 100,000 soldiers officially remained in uniform in the new army or Reichswehr. These professional soldiers tended to be conservative and their officers were reactionary.

Part III: A Republic on Shaky Ground: Right-wing Control Within the Weimar State

Soliwebzine: It seems that in addition to the military, the courts were not reliable supports for the new republic

Bill: The courts punished revolutionaries on the left much more severely than the counter-revolutionaries on the right. Most of the people on the right were treated with kid gloves, because the courts were peopled by reactionaries held over from the old regime. So, the government failed to purge many of the institutions of the old system.

Soliwebzine: The treatment of Hitler and the Nazi Party itself is an example of how the courts tilted right.

Bill: After his failed putsch in 1923, Hitler was tried for treason and convicted. He received a five-year sentence, but he only served nine months and he was treated very well in prison. On the other hand, many on the left involved in revolutionary activity against the state were arrested; many were executed or sentenced to very long prison terms. Like the army and the courts, the police too, were quite conservative. These institutions were a threat to the Weimar Republic. You had the police units that were not reliable, military units that were unreliable, and courts that coddled the militant armed right.

Soliwebzine: What about the Social Democratic party outside of government? Did they take on the Nazis?

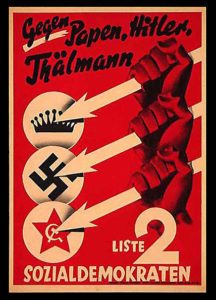

Bill: By the early 20’s the Nazis had created a street-fighting organization consisting of storm troopers (from the term Sturmabteilung or SA) known as Brown Shirts because they wore brown uniforms. They defended the party’s rallies and they attacked the rallies of their opponents; they were really tough street fighters. The Communists had their own street fighters who wore red uniforms and armbands and called themselves the Red Front fighters. And, by the middle of the ‘20s, the Social Democrats responded to this and organized a group called the Reichsbanner.

For a long time, they were by far the largest party-affiliated group; by the end of the ‘20s, they could put two hundred thousand Reichsbanner men in the streets at any given time. So, by 1930, you had three massive paramilitary formations, each one affiliated with one of these parties.

Another major para-military formation that existed was a right-wing veterans’ group called the Stahlhelm or Steel Helmets. This was also very important. The Steel Helmets were for a time bigger than any of the party formations. They participated in a lot of the street actions, generally siding with the right. So, that’s why understanding that Weimar politics were also paramilitary politics is important.

Soliwebzine: Apparently, the Nazis were quite clever in how they used their paramilitary troops.

Bill: Yes, as their organization grew, they used the paramilitary units on the one hand to sow chaos, but on the other hand to demonstrate how they would be forces of order if they came to power.

They were very highly disciplined. They did not attack enemy formations willy-nilly. They only did so in accordance with orders from above and they were generally used on a day-to-day basis to demonstrate the Nazis as a force of order against the chaos supposedly brought about by the republic.

On the other hand, because many middle class people feared the coming of communism, the Nazis tried to present themselves as a force that could be relied upon to “protect” public order. The Nazis were very effective at doing this.

Soliwebzine: The Social Democrats in power must have recognized what was happening and made attempts to control the police and army, get them to operate to meet their constitutional responsibility, to protect the Republic. Did the leaders of the Weimar Republic try, and why did they fail?

Bill: Every state had its own police force—there was no national force. Most of the states in Southern Germany, like Bavaria, were very conservative, and not much was done there to change the basis of the police leadership.

Prussia was the most important of all of the federal states and had a police force of about 80,000 men. The police were under the control of the Prussian interior ministry and for most of the Weimar Republic, the Social Democrats controlled that ministry and they were able to remove most of the reactionary officials from the top of the police.

So, in Prussia, there was quite a bit of change in the leadership, in some of the other states, hardly any change at all. However, this doesn’t mean that the rank-and-file were cleaned out. A lot of policemen who had been policemen before, stayed on. These are just rank-and-file people and they’re basically left in their jobs. Some of them were conservatives; some of them were not. What’s interesting for us is to consider is that when the Nazis emerged as a mass party and they were able to put into the streets tens of thousands of their own paramilitary forces, the Prussian police basically obeyed orders, and worked to enforce the law against the Nazis as well as against the left.

However, although the Prussian police obeyed orders, I think it is important to recognize that the Social Democrats took way too long and were not thoroughgoing enough in their efforts to transform the police. This became clear, as we will see later, when the Nazis gained control over the Prussian police in 1933. They were able to quickly Nazify the police department and use it as their own instrument.

Soliwebzine: Eventually, after the chaotic and conflictual period from 1919 to 1923, the Weimar government gets some breathing room.

Bill: Yes, the government was able to stabilize the currency which brought a kind of stability to the whole social order. But by 1923 the Social Democrats were exhausted. As the most important party in power during the immediate post-war years, they were held responsible by the public for the government’s policies, which included suppressing the radical left, and many ongoing problems, such as the impact of hyperinflation. Many SPD members had deserted to the Independents and then to the Communists. Others withdrew from politics or left the trade unions, that struggled to protect their wages and jobs. And now the SPD leaders wanted to stay out of power, operate as a loyal opposition, and lick their wounds.

The Social Democrats, the Democratic Party, and the Catholic Center party had formed the so-called Weimar coalition of pro-republican parties in the Reichstag. Together, the three could generally form majority backed governments. In the elections of 1924, the left and the right lost ground, but without the SPD, the bourgeois parties still did not have a majority. The SPD agreed to support the minority cabinet in parliament, so new elections would not have to be called. For the next few years this arrangement seemed to function adequately. The SPD tolerated the minority cabinet and, at the same time, rebuilt its membership and organization.

Between 1924 and 1928, life seemed to assume a new normalcy, which is why people later came to regard it as a kind of golden age. It was culturally very rich. There was still a high unemployment rate of about 10% in the country, but that was better than it had been. Capital was flowing into the country because arrangements had been made with Germany’s creditors, including the United States, to bring in investment capital. So, German industry grew and modernized, adopting American productive techniques. In this period, there was more economic vigor; there was a lot of cultural creativity, and the government was relatively stable.

And some important gains were made during those years. For example, a law was passed to establish a real unemployment insurance system for the first time in Germany. This represented an important element of the safety net that the new constitution had promised.

As a result of legislative success and a general economic upswing that people really felt, in 1927 the Socialists decided that in the next election, if they did well, they would be willing to reenter government.

In the spring of 1928, there was a big election and the Social Democrats recovered a lot of their lost ground. They got 29%, which made them the biggest party in the parliament. The Nazis at this time had only 2%–which gives you a sense of how small the Nazis were, and the communists were down around 10%.

The Social Democrats were buoyed up by their strong showing and decided to lead a new grand coalition with three other bourgeois parties, one of which was very conservative, but was willing to join the cabinet. The Social Democrats in 1928 had really high hopes that they could finally begin to achieve some of the goals they had for social reform in the country. In particular, they hoped to strengthen the positions of the trade unions and make good on their slogan of promoting economic democracy. And then, within a year, the depression hit and all of their plans ran into a wall. The parties in the coalition fought among themselves about how best to manage the crisis. Interest group politics made it difficult for the partners to develop a coherent response to the country’s worsening economic and social conditions.

PART IV: The Great Depression, the 1932 Election, and the Nazi Seizure of Power

And in that debate, Rudolf Hilferding, a major Social Democratic Party thinker and government Minister of Finance, was quite influential. On his advice, the Social Democrats adopted a rather conservative approach to dealing with the onset of the depression. They were not as willing to shrink the social state as were the right wing parties, but they nonetheless basically supported a balanced budget and austerity. Meanwhile, as government expenses rose rapidly to cover the costs of unemployment insurance payments and to provide people with extremely modest social support, conflict intensified about how to cover these costs.

The debate lasted until March of 1930. The bourgeois parties demanded higher taxes on workers’ consumption, in particular beer, and the Social Democrats said, “no; we have to find the revenue elsewhere, maybe from capital.” The government collapsed and new elections followed in the fall of 1930.

It was then that the Nazis achieved their initial breakthrough, winning about 18%. As the Nazis grew on the right and the Communists grew on the left, the pro-parliamentary center shrunk, and nobody was willing to work with the Social Democrats. This situation made it impossible to form a workable coalition government. Instead, the monarchist President, Paul von Hindenburg, appointed a series of increasingly anti-republican Chancellors who he permitted to rule by emergency decree. Between 1930 and 1933 there were several elections, but in each one the Nazis and Communists grew stronger and the Reichstag remained paralyzed. Parliamentary government was essentially transformed into a presidential regime dominated by reactionary Chancellors who aimed, ultimately, to create some kind of authoritarian state.

Soliwebzine. The left remained totally split throughout this period, even as the forces of the right were growing.

That’s right. You had a number of disasters converging on the left. On the one hand, in Russia in 1928, the COMINTERN had issued a directive arguing that the world was about to enter into a new economic crisis and that this would lead to intensified class struggle and in that intensified class struggle, the Social Democrats were more dangerous than the Nazis, because they were really fascists in red clothing. And Stalin said at that point that the fascists and the Social Democrats were in effect twins, and it was the duty of the Communist parties to defeat the Social Democrats first. So, now the gulf between the communists and the socialists, already made very deep by the mistakes during the brutal conflicts of 1918-1919, when the SPD crushed the left, deepen even further.

Meanwhile, the Social Democrats continued to treat the Communists as a threat and when they were in power, either at the national or the regional level, they often used their police forces to put down the Communists in the streets. For example, in 1929, in what became known as bloody May Day, the Social-Democrat-led coalition government in Prussia banned a May Day march in Berlin which had been called by the Communist party. The Communists defied the order and were met with violent police action in which 32 people were killed

These conflicts, and the rhetoric with which each leadership accused the other of terrible crimes, made a rapprochement between the two major left parties basically impossible.

Soliwebzine: What about the situation on the right? After the failure of Hitler’s putsch in 1923, the Nazis switched gears toward building a mass party, promising everything to everybody.

Bill: Right. Hitler developed a new strategy, which I, along with many other historians, have called a pseudo legal path to power, in which you use the instruments of the parliamentary republic to destroy the parliamentary republic, you use parliament to destroy parliament.

And this is where you have a kind of dialectic between the legal path to power in which the party puts up candidates and runs campaigns and operates like a parliamentary party, and the extra-legal path where, at the same time, the party foments riots, attacks people in the streets, breaks up the rallies of its opponents, spreads disinformation in its press, does all these things to create chaos and to simultaneously sell itself to the population at large as the only force that can bring about order.

From 1924 until 1929 and ’30, when the depression hit, the party remained small; it had about 100,000 members, mainly men. But, in that period, it built a national structure and it had a dedicated, energetic cadre operating at the local level, establishing local party offices, training speakers, building infrastructure.

And so, when the collapse of 1929 occurred, the party was extremely well-positioned to build on this infrastructure and win mass support, taking advantage of the growing anger at and disillusionment with the government.

After 1930, the Nazis began a very steep electoral climb, moving from 2% in 1928 to 18% in 1930 to the peak of 37% in the summer of 1932. First, they began to absorb a lot of the small right wing groups that had been formed in the ‘20s. Then, as conditions declined, as people detected the country slipping into chaos, many in the middle classes began to turn to the right and they left the moderate bourgeois parties. For example, the Democratic Party got 20% in 1919 and had declined to about 1 or 2% in 1930.

So, the bourgeois political center began to dissolve. The Catholic Party was the one exception; they were able to basically hold themselves together almost to the end. But, all the other bourgeois groups began to dissolve, as their former supporters turned to the far right.

After 1930, Social Democrats did not participate in the national government, but they cooperated in parliament. They did not want the government to fold, because that would initiate more frequent elections, and they feared that each election would only help the Nazis to become stronger.

For the first couple years of the depression, the labor unions went along with the austerity policy. But in 1931 and ’32, they began to talk about some Keynesian-like policies such as public works spending that would be deficit financed. Although efforts were made to push that line to the party leadership, the Social Democrats said no. Hilferding again played a big role, because he believed, along with many other economists of the day, that deficit financing would rekindle the kind of inflation that had devastated the country in the early 20’s.

Meanwhile, the Nazis didn’t give a damn about what had happened in 1923 and they, in fact, promoted deficit financing, claiming, “when we come to government, we’re going to spend whatever it takes to rebuild the country.” They had a lot fewer compunctions than the Social Democrats, who thought it was irresponsible to make those sorts of promises.

Soliwebzine: This must be one reason the Nazis began to win more votes.

Bill: That’s right. The Nazis were particularly skilled at telling every group whatever they wanted to hear. They were extremely effective, for example, in the countryside. Thirty percent of the population lived in the countryside. You still had a big peasantry in the 1920s. The peasants were really suffering and the Social Democrats had almost no standing among them. Partly this was because, good Marxists that they were, the SPD figured the peasantry was going to disappear, and anyway why should we appeal to these petty bourgeois forces? Meanwhile what did the Nazis say to the peasants? The Nazis said, “we’re going to offer you better prices. We’re going to pay you whatever it takes to keep you afloat.”

In the late twenties, when the Social Democrats realized, oh, my god, the peasants are voting, 60, 70, 80% in some places for the far right, we have to offer them something, it was way too late.

Soliwebzine: Tell us about the end-game. How does Hitler finally take power?

Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933. He was appointed because conservative elites around President von Hindenburg thought he could be used for their own ends. By bringing Hitler into the cabinet, they believed they would be able to use the Nazi parliamentary delegation, the largest in the Reichstag, to alter the constitution and transform the republic along authoritarian lines. They believed they could manipulate Hitler, but he outfoxed them.

Once appointed, he used the pretext of the Reichstag Fire to convince President von Hindenburg to declare a state of emergency and allow him to rule by decree. There is much debate about who set fire to the parliament building, although it was blamed on an anarchist who had been a Communist party member. But the important point is that this “attack” on the state allowed Hitler to pose as the defender of the political order and he was able to assert that unless he had emergency authority, then Germany would slip into chaos and would become vulnerable to a Bolshevik seizure of power.

Hitler used this emergency power to crush the Communists, to also begin to round up Social Democrats and to threaten all the other political groups in the country. This set Germany on the road to a one-party state that was achieved within about five months.

Here you see how the Nazis used the pseudo-legal road to power. Everybody should remember that. They used democratic means to destroy the democratic state. So, Hitler was extremely skillful at manipulating elections and manipulating plebiscites, or public referenda, to secure legitimacy through the popular vote or through votes in the Reichstag.

So, for example, in March of 1933, there was a Reichstag session in which all the parties, with the exception of the Social Democrats, voted to pass what was called the Enabling Act, which gave him sweeping powers for four years. They used a kind of democratic mechanism, something we would associate with parliamentary democracy, to essentially vote away the power of the Parliament and hand it over to this strongman.

Soliwebzine: And the Nazis/Hitler went after the media, as well. There was a very vigorous press that opposed them and vigorous political parties on the left who opposed them.

Bill: That’s correct, but he didn’t do it all at once, and you have to remember that. It took months. He did it using a combination of means. Some newspapers, like the Communist party newspapers were simply shut down and later on, the Social Democratic party newspapers were shut down when the party itself was abolished. Other newspapers that were not party-affiliated newspapers were heavily censored and over time, they were effectively bought out by the Nazi Party or by the German state. And so, it was a combination of censorship, buying out and the use of a ban that over time allowed the Nazis to bring all of the newspapers into line. The term the Germans used was the Gleichschaltung, which means effectively to bring things into line, to Nazify them and that took some time.

Soliwebzine: Hitler’s ability to neutralize and petrify the opposition depended on his ability to control the men with the guns and give them power. Within the military or the police, was there any resistance to what Hitler was doing? If so, how did he end that challenge?

Bill S: First, we have to be very careful. We need to be very clear that in 1933 in Germany, the army was intensely nationalist and opposed to the existence of the republic. So, many in the officer corps were very pleased with the Nazi seizure of power. They were anxious, however, because the Nazis also had an army of paramilitary fighters, their storm troopers, which numbered in the many hundreds of thousands in 1933, and it was the storm troopers who took the fight into the streets against the Communists and the Social Democrats and basically unleashed a kind of civil war in the country, while Hitler was manipulating the political system to secure his appointment.

Once the appointment was secured, then the army was quite happy to see the democrats crushed and the unions smashed, and they were extremely excited about Hitler’s proposals for rearmament, but they were very nervous about the storm troopers. And so, in 1934, Hitler organized the decapitation of the storm trooper leadership. Basically, he had most of the SA leaders assassinated, including his best friend, Ernst Röhm, who was the most important SA leader. Hitler showed the army that, as the country rearmed, it would do the recruiting, it would create the officer corps and the SA would not be folded into the army en masse and basically water down the power of the general staff. So, that’s how he won over the power of the army.

In terms of the police, the police were by and large, a rather conservative institution in all of the different states. Some of the states were more social democratized than others, but one of the things that Hitler did when he took power was he appointed Hermann Göring to be in charge of the Prussian police.

The big showdown comes in 1933 after the Nazis had power, that is, after they had gained a place in the national government. They got the Interior Ministry, not just of Prussia, but of the whole country and they used the Interior Ministry to deputize their paramilitaries and basically convert them into police. So, they swamped the regular police force with their own men. Even when there were loyal police forces among some of the German states, they were overwhelmed by this influx of pro-Nazi or pro-authoritarian units.

So, the Nazis actually learned quite a bit from the mistakes of the republicans. Where the republicans hesitated, the Nazis did not and they purged the state institutions of any perceived opponents very quickly, whereas in the early years of the republic, as I said earlier, the social democrats and more generally the republican forces, feared civil war and they hesitated; that was a huge mistake on their part.

By the time Hitler was appointed Chancellor the left faced not only the army, but the police forces and the Nazi paramilitary troops. The socialists and the labor unions were quite fearful that if they undertook a civil war, they would lose, which is why they hesitated once again.

Soliwebzine: Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January of 1933 and by July all the political parties were banned. How does he deal with other institutions that might be sources of opposition—for example, universities or the Catholic church.

Bill: On social questions, the Nazis were pro-family, anti-homosexual and so on. And all of these things were right in line with church teachings. The Catholic Church was wary of the party, fearing that the Nazis were going to intervene or interfere with the operations of church schools, of church youth groups, church institutional power.

Hitler cut a deal with the Pope in the spring of 1933; Hitler says, we’ll leave to you your schools, your youth groups and so on, in exchange for your agreement to dissolve the Catholic Party.

The Pope agreed, and the party was dissolved in the spring of 1933. The Catholic Party represented 20% of the electorate, so it was very substantial. And Hitler won a lot of support for his ability to compromise with the church there.

However, once the party was dissolved and Hitler got what he wanted, he basically did what he said he wasn’t going to do. He intervened in school policy and he dissolved the Catholic youth groups and so on, but by then the church was in no position to resist.

Regarding the universities, there wasn’t much that the Nazis had to do to win their support, because the universities were full of reactionaries in the 1920s. The student groups were basically dominated by the right. The Nazi student groups were by far the largest. The professoriat was extremely conservative and behaved shamefully when the Nazis took power and purged the universities of all Jews, democrats and Social Democrats, anybody they perceived to be a threat. The bulk of the professors applauded or didn’t say anything; and they were very happy with the so-called national revolution. The great example is the philosopher, Heidegger, who essentially became the rector of the University of Freiburg in 1933 and was regarded as a pro-Nazi figure. So, there was no resistance from the universities really worth mentioning. They behaved shamefully.

The liberal political groups all self-dissolved. So, in the spring of 1933, as I mentioned earlier, Hitler got all the parties in the Reichstag with the exception of the Socialists (the Communists had already been outlawed) to pass an enabling act, which gave him dictatorial power for four years. And in the wake of that, it proved pretty easy for him to pressure each of the bourgeois parties essentially to either fold themselves into the Nazi party or simply to self-dissolve, and they all did it, one after the other.

Soliwebzine: So they were intimidated?

Bill: There were intimidated and they were excited at the prospect of what they were calling the national revolution. They wanted to be a part of this national revolution and the national revolution was predicated on the idea of unity and to have a fractured polity with different political parties competing for power was regarded as unacceptable.

Part V: What Can We Learn from this History?

Soliwebzine: Let’s turn now to the lessons to be drawn from this history.

Bill: If you look at the German example of 1933 and if you look at the Austrian example of 1934, in both cases, you see socialist movements that are defeated by fascist movements, even though the socialists have very large membership rolls and they have large paramilitary formations that they try to use to defend their interests in the streets.

And the reason why they lose in both cases is that they don’t have control over state power. Even though the states were both ostensibly parliamentary states, they were actually under the control of people who were not interested in preserving the constitutional democratic order and, therefore, the institutions of the republic were not reliable. And once that became clear, that opened the road to the fascists to take power.

Soliwebzine: This point about the left’s paramilitary organizing is interesting because many on the left today argue that Hitler was successful because no one, including the left in Germany, took him seriously enough at the beginning. They argue that unless the left directly, physically, confronts far right groups now when they are a small minority, they will grow to monstrous proportions. In support of this approach, this statement (attributed to Hitler by Goering) is often quoted: “Only one thing could have stopped our movement – if our adversaries had understood its principle and from the first day smashed with the utmost brutality the nucleus of our new movement.”

I think that it is the job of the democratic state to crush illegal actions carried out by rightist paramilitaries. To argue that left-wing paramilitary forces should “smash with utmost brutality” the forces on the right is to argue for chaos and disorder on the streets, a condition that simply strengthens the claims of the right that the republic is weak and unable to maintain order. The left needs to win state power and to use the institutions of the democratic state to protect people from fascist violence. The Weimar state failed to do so and this made it look weak and illegitimate in the eyes of the public. While the Communists and Social Democrats often did confront the Nazis in the streets, paramilitary conflict only strengthened the position of extremist forces that pointed to the republic’s weakness.

We also need to build powerful extra-parliamentary organizations that can represent a non-violent counterpoint to the right and can press the government from the outside for what we want. That should include the demand that the state root out violent opponents of the democratic state and protect the interests of the people.

Soliwebzine: The Weimar regime, including the SPD, were willing to use state repression against the left and the right, although more harshly on the left. There is debate today about whether or not the state should tolerate right-wing extremists taking public space. What lessons do you draw from the German experience?

So, one of the things that I’m concerned about when we talk about confronting the fascists with an iron fist, using every means including physical confrontation, to drive them out of public space and obliterate them as a political presence, I’m not sure how you do that without undermining some of the fundamental advantages that we have gained in the construction of the democratic republic, particularly constitutional protections that we all think should be maintained?

I think on the left we have to have a conversation about what we think of the democratic republic. Do we think that, it is a vehicle that we can use to build our power, and to move toward the goal of socialism that we want? Or is it something that we should disdain? Is it something whose rules apply or not apply evenly across the board.

When you use phrases like “obliterate them as a political presence,” or “confront them physically” and so on, you’re asking the state to do certain things to them, to the fascists, that we wouldn’t want done to us, and that worries me.

Soliwebzine: From the early 20’s the left was deeply split such that even in the late 1920’s when the Nazis were clearly on the rise, the SPD and the KPD did not join forces politically. How significant was this split in accounting for the Nazi victory? And if it was significant, what are the implications for the left in the US today?

Bill: During most of the republic’s history, the SPD received support from roughly 30 per cent of the electorate and the KPD about 10 percent. With Socialists and Communists fighting each other in the streets, organizing competing trade unions, and at odds in parliament, they were unable to concentrate their forces for joint action against the Nazis and their anti-republican allies. Communist opposition to the republic’s existence helped to undermine the parliament’s ability to function, undercut the legitimacy of the democratic state, and strengthened the hand of the right.

Soliwebzine: You make the argument that although the Social Democrats were elected to office, they never really had control over state power. The Weimar republic was quite new and still riven with authoritarian, conservative forces. If a social democratic party were elected here, would they face the same or different problems?

If a Social Democratic party were to win power here, it would have some advantages that the German Social Democrats did not have in the Weimar Republic. I would argue that the United States has a long democratic tradition and the majority of the people and most state officials actually believe in the principles of the republic. So, if the socialists won a majority in Congress, I think most officials would carry out the laws and policies the congress would enact. That is not to say that there would be no resistance or foot dragging on the part of some officials, but we are not dealing with a context in which the monarchy has just fallen in the wake of catastrophic military defeat. Conditions would be much more favorable for the implementation of social democratic reforms.

Of course, that situation could change if conditions lead to the democratic state’s loss of legitimacy in the view of large numbers of Americans. That legitimacy has been declining over the last 40 years under the relentless assault of the neo-liberal ideology pursued by especially the Republicans, but also the Democrats.

That is why, in our struggles here in the United States, it seems to me that we have to mobilize forces in the streets, to put pressure, not only on the groups against whom we’re trying to do battle, so against the far right, but we want to keep pressure on the government to make sure that the state consists of institutions that respond to the people’s needs, both material and political, in democratic, constitutional ways. That is essential. It’s especially true in regard to the police.

Soliwebzine: In the US today there is in effect a national police—homeland security, the vast coordination, information and communication systems among local police departments, the militarization of the local police, etc. If the Nazi road to power relied on a conservative and anti-republican state apparatus and the Nazis were able to make a deal with both the military and the police forces, what are we going to do about that today in that the police and the military are aligning with conservative law and order politics.

Bill: Well, you have to win political power to combat and reverse the tendencies you describe. Control over the national, state, or local governments gives power holders the chance to reshape the police, whether its homeland security or the town police department. It is clear that the political character of the government matters. Police forces vary in their quality and their political character (although obviously, much more reform is necessary). The Social Democrats in Germany were unable to fully reform the police because they feared the repercussions of acting decisively. At different moments, they feared a violent response.

We must learn from that and, when we confront police forces that are out of control, we must be willing to bring them to heel. Many police departments in the United States have responded to political pressure and changed for the better. Others have not. It is an ongoing struggle in which organizations such as the ACLU can play an important role by turning up the heat on those in office. It is a place where socialists and liberals can and should work together.

Soliwebzine: In the early days of the republic, both the army and the police remained loyal to the government on the whole. And this was partly because the new government had broad popular support. It seems that in the crucible of the 1929 crash, the government’s failure to relieve suffering, the hostility of much of the revolutionary left toward the government, and the failure of the social democrats to organize at least some of the petty bourgeoisie (e.g. the peasantry) to their side, public support for the democratic republic waned and therefore that brake on the conservatives within the military and the police also disappeared. Again, what lessons for today might we draw here?

Bill: The history of the military in the United States is very different from that of Germany, where the power of the army and the monarch were linked and the army resented its loss of authority after 1918. In the United States the army has never directly challenged civil authority through an attempt to seize power. I am not arguing that militarism is not a problem here. It certainly is. We have a culture of militarism that allows the armed forces to absorb far too many resources and which promotes mass and elite support for an imperialist foreign policy. Our generals also have enormous influence over the making of government policy. But thus far they have never attempted to assert direct control over the civilian government and they generally respect the principles of the republican order. Of course, that could change if a socialist government in the United State radically cut military outlays and reversed US imperial policy. To undercut military resistance to such changes, it will be important to educate Americans about the role of the military and to win broad support for such changes. That should be at the heart of any socialist movement building and electoral strategy.

Soliwebzine: You make the point that the Nazis were very good at producing havoc in the streets and then presenting themselves as the guarantors of law and order. Thinking about the right in the US today, what conclusions do you draw from the German experience in terms of effective strategies that the left might use.

I do not believe that the left should organize paramilitary forces to confront the violent neo-Nazi and other far right formations. Violence by “left” groups like the “black bloc” alienates vast swathes of the population we need to win over. We need to win by force of numbers and we need to master non-violent techniques to protest against state policy and to counter the right. We must educate our constituency, train it for various forms of protest and demonstrations, which can include methods of self-defense, and convince people that we are not like our opponents, but are their opposite. At the same time, we need to win over the police and army to our side. As Engels knew well, victory in fights on the barricades stand little chance of success against modern armed forces. Victory is much more likely, though, when the army and police go over to the people, as occurred in the Russian Revolutions of 1917.

Soliwebzine: The depression seems to have been a real political turning point. One of the key mistakes of the SPD was the commitment to austerity—it seems that this was fateful because they were unable not only to do anything but even failed to propose a program that appeared to counter the impact of the economic crisis.

Bill: Yes, one key reason the Weimar Republic failed is that the people did not regard the institutions of the republic as legitimate. They did not feel the republican institutions functioned in their interest. And it seems to me that that’s the fundamental reason why the Social Democrats were unable to build the majority that they wanted.

I think that part of the problem was that the SPD were never able to actually make the state theirs. Wherever they were in power, they were always in power with others. And so they were always forced to make concessions and compromises in ways that I think in the end undermined the credibility of their project.

Soliwebzine: as the depression deepened and the government failed to act, this was a real problem

Bill: It seems to me that we have to be concerned about the state functioning better and meeting the needs of the people better, so that it has legitimacy in the eyes of the people and can then be expanded. It is the rights that we have, the services we expect, the reforms that we want, these can be built on the basis of institutions that have popular support. But, if the people don’t see the state as legitimate, if they see it as a failure, a parasitical entity that sucks their blood and meanwhile represses them, then the republic will lose its legitimacy.

Now, there are people on the left who would argue that the republic is illegitimate; it’s a class institution and should be destroyed; we need to build something else. That is easier said than done. There are others who argue, and Marx and Engels argued this, that the bourgeois republic is the terrain upon which you fight for socialism.

We know that ultimately revolution probably will not come peacefully through capturing the bourgeois state—the coup against the legitimately-elected Social Democrat Salvador Allende in Chile is a perfect example. Yet, whatever form this endgame takes, reform struggles are an important vehicle for building working-class power toward this moment of revolutionary possibility.

All reforms are not created equal; some have far more potential for challenging capital and organizing social power than others. As revolutionaries, we should be paying attention to the kinds of reforms we propose, the ideas we use to argue for them, and the organizing methods we employ. At every point we can make a choice for reforms that are more radical, arguments that challenge capitalist common sense, and more democratic modes of movement-building.

For example, labor unions can demobilize and pacify workers and promote pro-capitalist ideas. But fighting, democratic unions can operate to prepare the class in their understandings, organization, and forces to challenge capital not just for a bigger slice of the pie but for a genuinely different pizza

One of the things that I fear in our own society among many people, is that any sense that the state can do anything for them is crumbling. They see the world increasingly as this world of elite domination in which little people can only do best by watching out for their own individual asses. And if that means having a howitzer in your living room to keep the federal government out, then that should be legal.

And that, to me, is a really big danger sign. The democratic republic that we live in has been a flawed institution. But if you think about what’s happened over the past 200 years, people have been able to change it. That doesn’t mean that you’re going to have increasing democratization forever. The opposite can occur. That’s my great fear.

But let me conclude by saying that this is a moment of great concern, but it’s also a moment of great opportunity. I’m hoping that the left can use the opportunity skillfully and successfully.

This article began as a series of interviews with Bill Smaldone by Bill Resnick on the Old Mole Variety Hour, KBOO radio, 90.7fm, Portland, OR. Johanna Brenner and Bill Resnick then interviewed Bill Smaldone for Solidarity’s Webzine.