Marius Pontmercy

February 12, 2018

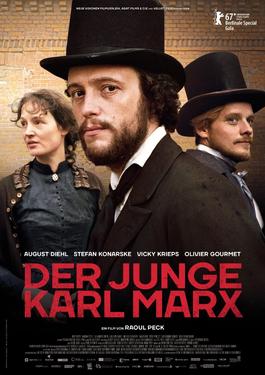

Raoul Peck, the Haitian-born director of Lumumba (2000) and I Am Not Your Negro (2016), has a new film. The Young Karl Marx, a period drama, recounts the life of the founder of communism between his exile from Germany in 1843 and the publication of The Communist Manifesto on the eve of the revolutions of 1848.

Justly described as a bromance by some reviewers, the film’s central story-line is the blossoming friendship of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. But Peck doesn’t overly romanticize these figures. On the contrary, he depicts them with human weaknesses and desires. More importantly, Peck shows us Marx and Engels as inter-organizational activists, at a time when the socialist left was nascent and disorganized, but poverty and injustice were pushing people towards a breaking point. We also see that, even before the The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels’ writing grew directly out of their efforts to organize the political and economic power of workers.

Marx and Engels spar with Proudhonists, exposing their failure to account for the growing divide between bosses and workers, but then team up with the Proudhonists against the German idealists; for, though pulling no punches in their critique of Proudhon, Marx and Engels were prepared to acknowledge the Proudhonists’ successes in building a base among French workers. Basically, Peck depicts Marx and Engels as upstarts with a purpose. Their tactics could be sloppy, but they were also strategic—and ultimately successful in earning the respect of the French socialists.

The film (surprise!) is not being shown in AMC theaters, despite the success of Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro. I saw The Young Karl Marx at the Coolidge theater in Boston’s Brookline neighborhood, at a screening sponsored by the Goethe Institute, a German cultural organization. The Coolidge is not your ordinary movie theater. It has the feel of an old theater or cabaret – a fitting space for a period drama. I arrived early, even though I expected that I might be one of the few attendees. (I thought that, besides myself, there might be just a group of sectarian leftists.) I couldn’t have been more wrong. The audience was large, and skewed towards an older demographic, but not exclusively. I saw what seemed to be a few extended families, from grandparents to grandchildren, coming and sitting together. Many of these families and older couples were speaking in German; it was heartening to see this film in a foreign-language cultural milieu akin to those that were once vital to the U.S. left. Who knew there were so many expat and immigrant Germans in the Boston area? What other groups like this might exist elsewhere in the US – or could exist, with the right organizing effort?

I also noticed quite a few younger Americans, about my age, but not the leftist sectarians I had expected. Judging by their conversation, they seemed to be liberals whose interest in this film was sparked by the talk of socialism during the 2016 presidential election, by everything that has happened since then in US politics, and by the centenary of the Russian Revolution. These were people who seemed newly open to radical politics.

Peck with cast members.

Peck with cast members.A woman from the Goethe Institute took the stage to introduce the movie. She explained that Raoul Peck had come to film through activism while a student in Germany in the 1970s. “Marxism was in the air everywhere among German students in the 1970s. Raoul took a seminar in the university about Marx at the same time he got involved in making film for German public television,” she said. She described the movie as a labor of love: Peck had begun work on it ten years ago, but obstacles slowed production. (In interviews, Peck has attributed those obstacles in part to political opposition to his project among government funding bodies.) Perhaps what is most subversive about this film is that Peck portrays Marx and Engels as human beings, and not mythological and untouchable historical figures.

After the film, as I was walking back to the nearest T stop, I encountered some young activists who were collecting signatures for a petition to place a $15 minimum wage and paid family sick leave on the ballot in Massachusetts. I pointed them in the direction of Coolidge theater, explaining that a movie about Karl Marx had just let out. They thanked me and walked over to meet the crowd.

Marius Pontmercy is a member of Solidarity.