Emily Pope-Obeda

May 28, 2016

While the machinery of deportation has reached an unprecedented scale in recent decades, its roots are both deep and critical for understanding its place in modern U.S. society. The massive infrastructure for removal that looms over the nation’s immigrant population has its underpinnings in the early 20th century.

This article will examine the growth of the deportation regime during the 1920s, and explore the enduring ramifications of early deportation practice and the renegotiation of the state’s coercive power over migrants. It will particularly emphasize how deportation and migration control evolved to serve the interests of the modern capitalist nation-state, both in controlling the flow of precarious labor, and in the direct service of private profit through immigrant removal.

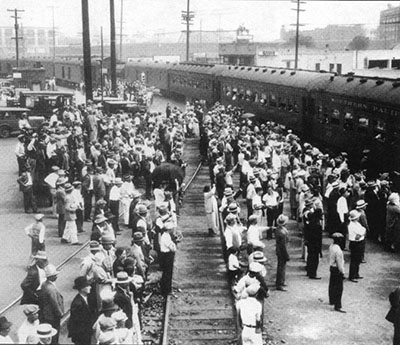

Mexican Americans being deported by rail, ca. 1931.

Throughout the 1920s, as the federal government consolidated its practices of deportation under a newly efficient, centralized system, financial expediency was chief. Frequently, railway lines wrote to immigration officials selling their credentials as possible deporters, and offered incentives to gain lucrative government contracts. A September 1924 letter from the District Director of Immigration at Kansas City, Missouri to the Commissioner General reported that the Katy Road Railroad Company had offered “inducements to the Immigration Service for this deportation business”: furnishing of guards and free passage for the Immigration officers, meals for deportees at fifty cents apiece, and a special Pullman tourist car, as well as the right to appoint guards of their choosing.1

By the end of the 1920s, with the “deportation business” booming, the state as well as agricultural and industrial interests carefully calculated how to maximize their profits.

Although the average yearly deportations over the last decade have increased 200 fold since the 1920s, what is striking in each decade is the rate of acceleration. During the 1920s, deportations escalated from 2,762 in the year 1920 to 16,631 for the year 1930.2 Once again, in the most recent decade, deportations have spiked rapidly over a short time span, from a previous record high 211,098 removals in 2003 to the record high of 438,421 removals in 2013. This growth, which has earned president Obama the unflattering moniker of “Deporter-in-Chief,” reflects a far longer trajectory of rising deportations over the last century. Falling between the more commonly cited deportations of the so-called “first Red Scare,” and the mass removals of Mexican Americans during the Depression era of the 1930s, the 1920s were a critical period for the consolidation, systemization, and growth of the deportation state.

Rise of Deportable Labor

During the 1920s, as the Quota Acts and increased coordination between institutions transformed deportation from a more limited, targeted system to a broader, more encompassing dragnet, the state renegotiated its powers of social control and policing. Individual states had exercised their own forms of immigration control since the colonial era, but it was only in the 1870s and 1880s that the United States consolidated its first federal immigration laws. The nation did so in line with accelerating and diversifying migration, as well as rising industrialization and increased global mobility of unskilled labor migrants.

The 1875 Page Act, the first exclusion law enacted by the federal government was designed as a labor control act, barring “alien convicts,” prostitutes, and “coolies.” In 1882 the federal government extended the excludable classes to include “any convict, lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge,” as well as creating the first federal legal infrastructure for removing and returning undesirable migrants and banning most Chinese migrants.

It is telling to note that in the early decades of the 20th century, authority for immigrant removals was vested with the Secretary of Labor; only in 1940 was the Immigration and Naturalization Service (formerly the Bureau of Immigration) transferred from the jurisdiction of the Department of Labor to the Department of Justice, revealing how closely migration restriction was tied to labor control. The dramatic deportations of suspected radicals have had the most enduring grip on the public imagination of immigration control, but it is important to recognize that its role as a system and enforcement mechanism of labor control has been both more mundane and perhaps therefore all the more menacing.

By the 1890s additional exclusions were added, including “paupers,” people suffering from “loathsome or dangerous contagious diseases,” polygamists, and “persons whose ticket had been paid for by another.” The inclusion of paupers, physically impaired, and those dependent on others for travel expenses reflects the abiding concern with the exclusion and removal of those who might become dependent on public welfare.

The 1891 act also provided legal grounds for the removal or post-entry deportation of those who were “liable to become a public charge,” or had become public charges after their arrival. By 1903, additional classes included epileptics, the insane, professional beggars, anarchists, prostitutes, and procurers, and in 1907, the list grew again with the inclusion of “imbeciles,” “feeble-minded,” persons with tuberculosis, persons found mentally or physically defective, persons having committed a crime of moral turpitude, persons whose tickets had been paid for by a private organization or foreign government, and unaccompanied children.

In short, anyone deemed unfit to be a productive, compliant member of the burgeoning industrial workforce was unwelcome. Subsequent legislation during the 1910s and 1920s extended the period of time after entry within which deportation could be effected, creating an even more elastic and vulnerable migrant labor force.

As mass removals of Mexican Americans during the Great Depression demonstrated, deportations provided an important state mechanism for ensuring the labor pool of the nation could contract and expand at will. This served both corporate interests–guaranteeing a cheap but vulnerable labor force that faced removal if they spoke out or demanded higher wages–and also government interests, by making sure that migrants could be removed when they became public charges, attempted to draw on government services or benefits, or became entangled with governmental institutions such as prisons or hospitals.

Beginning in the early 20th century, the federal government did not just wait patiently for deportees to be rounded up in mining towns, lumber camps, or agricultural fields when economic needs dictated. In fact, it actively reached out to local governments asking for lists of potentially deportable public charges who could be made ready for the next regularly scheduled deportation transport.

Deportation has never merely been an enforcement arm of immigration restriction or extended border control. It has always maintained a more central function at the heart of regulating and maintaining the authority and smooth operation of the capitalist nation-state.

State Institutions and Deportation Terror

Then as now, the infrastructure required for apprehending, detaining, and physically transporting thousands of immigrants a year was vast, and its successful creation acts as a marker of the intrusive, militarized, social control of the population. One of the most essential and overlooked significances of deportation in the 1920s was the standardization, centralization, and planning imposed, which undergirded the rise of deportations in subsequent decades.

Although the deportations of radicals at the end of World War I have held a particularly important place in national memory, these were a minority of total deportations, even at their height, and fail to reflect the less-visible, everyday deportation machinery being standardized during the 1920s. Most deportees were not victims of free speech repression captured in sensational raids. They were men imprisoned in county jails for petty theft, children receiving treatment for illness in public hospitals, and women receiving public aid to keep their families fed.

This evolving machinery was premised on the ability to coordinate among federal, state, and local governments, to increase contact with institutions throughout the country, and at the end of the day, to keep the trains running on schedule. The INS coordinated deportations on an increasingly regularized and frequent schedule throughout the decade, communicating with dozens of regional subdistricts to consolidate deportation parties for pickup at major districts across the country. As the contemporary debate often reveals, much of deportation revolves around the capacity to remove foreign-born laborers from the country as soon as they seek the services, benefits, and rights provided by society.

The Commissioner General of Immigration corresponded regularly with the District Heads, demanding lists of potentially deportable charges at all of the public institutions in their area, including prisons, hospitals, almshouses, juvenile reformatories, and insane asylums, with the intention of rounding up any foreign-born residents who had become a financial burden to the nation. This system acted as a rudimentary version of the modern Secure Communities program (recently replaced by the Priority Enforcement Program), which runs the information of arrested individuals against federal immigration databases, and sends the arrestee’s fingerprints to ICE to find potential deportable matches.3

Today, while apprehension and deportation from jails has received the greatest scrutiny, other institutions continue to be bound up in the removal of those posing a financial burden on public or private services. Hospitals, although acting outside of the directed policies of federal immigration officials, have gained attention in recent years for the practice of “medical repatriation” (sometimes referred to as medical “dumping”) of non-citizen patients who are coerced or pressured into removal to their nations of origin when unable to pay for medical services, often at great danger to their health.

The Center for Social Justice explains of this practice that “acting alone or in concert with private transportation companies, such hospitals are functioning as unauthorized immigration officers and deporting seriously ill or injured immigrant patients.”4 This practice echoes the efforts of immigration agents in the 1920s to eliminate migrants who didn’t possess healthy, hearty enough bodies to be considered useful laborers.

As disability historians have begun to examine, some immigrants were excluded not for any specific disease or debility, but merely for having a “weak physique” (a label often used particularly against eastern European Jewish migrants), which convinced officials that they ought to be categorized as “likely to become a public charge.” In this way, the developing institutions of modern American society in the early 20th century, from explicitly punitive institutions like jails and reformatories to public welfare institutions like hospitals, were all brought together as part of the carceral arm of the government-corporate deportation agenda.

The steep increase in deportations demonstrates more than a fervent public sentiment against immigrants; it reflects the development of an unprecedented capacity to surveil, apprehend, and remove unwanted non-citizens. In transforming the regulation of undocumented migrants, one of the most critical contributions of the 1920s was in fact in creating a more organized system of documenting and tracking non-authorized individuals.

Despite the emphasis on dramatic raids and violent repression of radicalism, most of deportation was about a far more pedestrian and, I would argue, more ominous form of social control. Rather than eliminating a narrow ideological threat, deportation was a broader project of corporate-governmental collusion for controlling the flow of labor.

As the growing deportation machinery brought the federal government, local police forces and institutional bureaucrats into contact, they worked together to continue to expand the reach of the INS into towns and communities across the country. At every step, immigration officials struggled with the challenges of building an apparatus powerful, comprehensive, and efficient enough to transport thousands of individuals a year, from hundreds of U.S. cities and towns to myriad cities across the globe and, just as importantly, to do so within budget.

Profit, Detention, and Forced Return

Among the most disturbing aspects of the present deportation state is the clear profit motive, including the competition of private companies and local governments for lucrative detention contracts. Deportation activists have joined with prison organizers in decrying the damages done by the for-profit prison industry, which thrives on the incarceration of citizens and non-citizens alike.

While the for-profit prison industry in its modern incarnation is a new phenomenon, the profit margin in immigrant removal has deep roots, and expulsion has long been an enticing business opportunity for private companies. Throughout the 1920s, railroad lines, steamship companies, and food suppliers competed for the growing government appropriations for deportation, and in so doing established deportation as a tantalizing business endeavor.

The particular combination of racial nationalism and economic competition involved in enforcing deportation practice in the 1920s is evident in the 1928 correspondence between the Commissioner General of Immigration and the Panama Mail Steamship Company, in which the Commissioner states:

“The Bureau acknowledges receipt of your letter of the 24th ultimo, requesting that aliens destined to Mexico, Central and South America, be deported on vessels of your line or other American vessels when available, even though the rates are higher than either the Mexican or Japanese Lines which are now utilized. While the Bureau would be glad to patronize American Lines in deporting aliens, it must of necessity effect deportations at the lowest rates and unless you can compete with foreign lines, it is regretted that nothing can be done in the matter.”5

To sell themselves as strong contenders for deportation specials, railway companies relied upon their business records, arguing that if they were efficient transporters of goods, they could be relied upon to transport humans. The Wabash Railway Company wrote to the Bureau of Immigration in 1921 regarding the plans to move a large number of Mexicans from Saginaw, Michigan to “the Mexican Frontier.” The company had “handled a large volume of this Mexican business to Michigan, and from letters of commendation received from the sugar company, I believe that our service has proved as good, if not better than that of other lines.”

Starting in the early twentieth century, deportable migrants have been increasingly reduced to train fare and price-per-bed calculations. As anti-deportation activists have noted, the competition of private companies for ICE facilities is “a process that both lines corporate pockets with taxpayer money and turns human beings into commodities.” Today, as nearly a century ago, deportation reflects some of the most brutal, dehumanizing realities of the capitalist state, and so long as policing and punishment of non-citizen residents comes bound up with profit, immigration reform will remain stalled and ineffective.

As immigration officials in the 1920s sought to escalate deportations, they frequently struggled with the question of detention, which has arguably remained one of the most controversial and appalling facets of deportation practice. Before the rise of federal detention centers, the INS cobbled together a makeshift network on local detention facilities, county jails, and even at times, detention in the homes of private citizens. As the District Director of Immigration at El Paso reported in 1927, there was a massive overcrowding of local jails, unequipped to hold both the criminal population they were designed for and also detainees held for deportation. Indeed, he explained, deportees were being held in the houses of private citizens for lack of space in public institutions, such as the home of Mrs. Carmen Sanchez in Globe, Arizona at a cost of $1.00 a day, and the home of Mrs. Chavez in Tucson, at sixty-five cents a day.6

The growth of deportations was motivated not only by the calls of national leaders and nativist demagogues, but also from the pleas of localities heavily burdened by detention costs. Today, this system has grown exponentially and detention is often seen as a boon to local economies, with local governments often competing to house ICE facilities. Again, finance serves as a driver for the deportation infrastructure, as many of these localities “seek out such contracts with the aim of generating extra revenue, which only furthers the commodification of immigrant detainees.”

Immigrant activists block traffic at Broadview Detention Center in Illinois.

By now, the detention infrastructure has grown into a behemoth of incarceration, abuses, and profit. From the creation of the first private prison as an immigrant detention center in Houston, Texas, the revenue involved in immigrant detention has burgeoned. As historian Greg Grandin explains of the recent resurgence of deportations of Central American migrants since the start of 2016, “the deportation regime is completely dependent on the interests of privatized detention companies, with an over-militarized and arbitrary federal bureaucracy that terrorizes those that live under its thrall.”7 Yet while the massive network of detention centers looms large over immigrant communities, it has managed to stay, as one organization described it, “nearly invisible…vast, ever-changing, and shrouded in secrecy.”

By 2011, nearly half of all immigrant detainees were housed by private prison companies, including the Corrections Corporation of America and the GEO group, which have reported billions of dollars in detention profits over recent years.8 As of 2014, in spite of claims that DHS was conducting more targeted and selective detention practices, the agency was budgeting up to $5.6 million per day for immigrant detention, with a capacity of 31,800 detainees at over 250 facilities around the country.

Race, Removal, and Social Control

While I have emphasized the economic underpinnings of the modern deportation regime and explored the creation and evolution of immigration control as a powerful tool for ensuring and policing a pliable labor market, these functions are inherently intertwined with the racial and social functions of deportation. During the 1920s, as the Quota Acts were introduced and then refined, the federal government increasingly broadened and quantified its project of racially defining the national population through exclusions and expulsions. While Chinese exclusion had been on the books for decades and various categorical criteria for exclusion had been used unofficially to restrict particular ethnic populations, this marked the start of truly categorical racial boundaries for entering and remaining in the United States.

Since the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 abolished the quota system, immigration exclusion and deportation practice has reverted to an unofficial model of regulating the racial composition of the nation. Throughout the past century, immigrant neighborhoods of particular ethnic densities have been targeted for deportation raids; while current policy is ostensibly race-neutral, its impact is far from that.

As deportation scholars have increasingly noted, deportation holds a power far greater than the actual numbers deported; its impact lies also in the imposition of a regime of terror over immigrant populations, perennial vulnerability, and a persistent fear that at any moment, you or your family member could become a target. This has been critical in keeping undocumented immigrants from taking advantage of public services and resources, in suppressing protest and pushback against conditions, particularly in the workplace, and in allowing the state to continue to benefit from cheap unauthorized labor while refusing to extend rights and protections to those providing it.

Incidents in Chicago separated by nearly 90 years demonstrate the persistence of racially based enforcement of deportation law. In a 1926 deportation drive in Chicago, purportedly carried out to clean up Sicilian organized crime and rid the city of dangerous “mobsters,” the Chicago Police department raided the Italian immigrant neighborhoods of the city for weeks, picking up hundreds, including women and children. When detainees were turned over to the immigration officials to determine if they were deportable, agents found large numbers of Greek and Mexican people lumped in by their skin tone and residential proximity. While most of the detainees, Italian or otherwise, were ultimately not deportable, the raids and the smaller number of actual deportations had their more critical goal of terrorizing and controlling immigrant communities met.

The conjoined processes of racial profiling and immigration control remain rampant in Chicago, and just this past year gained attention when a May 2015 report demonstrated that 84% of DUI checkpoints in the city took place in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods. This trend not only demonstrates the continued, deeply-rooted structural racism of the police force, but also puts immigrant populations at particular risk, as apprehension for a DUI, considered as a “significant misdemeanor” by ICE, automatically makes an undocumented individual a “priority for deportation.”9

As many immigrant rights activists have emphasized in recent years, deportation and immigration control pose particular hazards to queer and transgendered immigrants who face additional vulnerabilities, including danger and violence in detention and return to hostile, threatening political climates. These dangers, while only recently a focus of public discourse, reflect a century-long connection between the policing of migration and the control or repression of non-normative sexualities. Much of the earliest federal immigration restrictions and deportation criteria arose out of an effort to ban or expel those perceived to be a risk to the sexual morality of the nation.

This took a multitude of forms from the exclusion of suspected homosexuals, unmarried women with children, and those with particular sexually transmitted diseases, to the racialized removals of women suspected of prostitution, women living out of wedlock with men, or men accused of bigamy. Throughout the 20th century, the ill-defined and therefore flexible deportation category of “crimes of moral turpitude,” allowed immigration officials great leeway in patrolling the morality of migrant populations.

Alongside the control of labor, one of the clearest agendas of the deportation state has been to enforce heterosexual traditional family structures as a criteria for belonging within the nation. Indeed, it is telling that even as LGBTQ activists struggle for greater protections under immigration law, it was only in the 1990 Immigration Act that the U.S. finally ended the practice of denying entry to homosexual migrants.

Describing how immigration authorities terrorize unemployed seamen in New York at the start of the 1930s, one deportation critic described the following scene:

“They are kicked and punched to waken them. They are grilled. They are accused of being [some] criminal for whom the dicks and police pretend they are searching… It is a weapon forged by government, to make it a lot easier for the bosses to reduce the workers standards, as a way out of the crisis. It is an important spoke in the capitalist wheel of war.”10

While the primary targets of immigrant enforcement officers have changed, the scene of immigrants wakened by ICE officers under false pretenses remain a familiar story. During a century when deportation practice rose from a small-scale, targeted effort to eliminate specific perceived “threats,” to a mass-scale project of social and labor control, deportation has again and again proven to be a critical weapon.

Emily Pope-Obeda is a sympathizer of Solidarity in Chicago.

Footnotes

1 National Archives, Immigration and Naturalization Services, Record Group 85.

2 Annual Reports of the Commissioner General of Immigration for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1930.

3 “Priority Enforcement Program,” U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement website.

4 “Discharge, Deportation, and Dangerous Journeys: A Study on the Practice of Medical Repatriation,” Center for Social Justice, Seton Hall Law School, December 2012.

5 National Archives, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85.

6 Ibid.

7 Greg Grandin, “Here’s Why the U.S. is Stepping Up the Deportation of Central Americans,” The Nation, January 21, 2016.

8 “The Math of Immigration Detention,” National Immigration Forum, 2013.

9 “Criminalize, Then Deport: Are Chicago Police Abetting Deportations,” Organized Communities Against Deportation, September 11, 2015.

10 Tamiment Library, RG 129-Labor Research Association Records.