by Nicholas Davenport

March 10, 2014

The question of what demands ecosocialists should put forward in response to the climate crisis is a pressing one. Robin Hahnel, in “An Open Letter to the Climate Justice Movement”, argues that the climate justice movement should demand a cap-and-trade policy, abandoning its traditional stance against carbon trading. To Hahnel, carbon trading is the most realistic way for society to make carbon emissions cuts in the necessary time frame, and, contrary to the arguments of activists, it can be done in a socially just way. Although I respect Hahnel as a sincere and principled radical, I find his argument troubling. I believe it is marred by a misunderstanding of activists’ arguments against carbon trading and, more fundamentally, a lack of attention to the dynamic of reform and revolution.

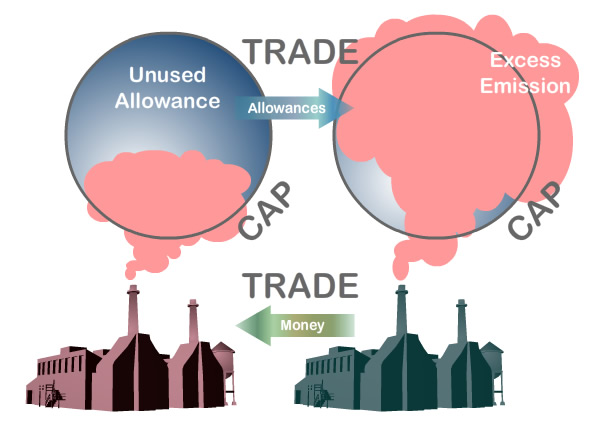

What is “cap-and-trade”? “Cap-and-trade” refers to a method of regulating carbon emissions where each country is allotted permits to pollute in accordance with a global a “cap” on emissions. Countries that don’t use all their permits can sell them to countries that need more, which, according to proponents, incentivizes emissions reductions. In theory, the system would be strictly regulated and the global cap would be reduced over time to bring carbon emissions down to sustainable levels, but climate justice activists argue that in practice, cap-and-trade proposals a ploy by global elites to avoid real action on carbon emissions.

Hahnel shortchanges the arguments against carbon trading. He acknowledges only three: that nature should not be turned into a commodity (a basically aesthetic argument which he easily demolishes), that Wall Street will take advantage of the carbon market and distort it (which, he argues, is a non-issue because even if there’s a financial market bubble, the number of carbon permits will be the same), and that corporations will be awarded bogus carbon credits (which would be impossible under the carbon trading system he proposes).

In fact, activists who oppose cap-and trade have made many other arguments against the system. For example, Larry Lohman, in Climate and Capitalism, argues that carbon trading is an antidemocratic system that interferes with positive solutions to the ecological crisis by supporting capital expansion rather than community-controlled alternatives (for example, favoring an energy company building a hydroelectric dam rather than the villagers practicing sustainable agriculture in the area the dam would flood). He also argues that carbon trading tends to prioritize the easiest cuts, usually in developing countries (which Hahnel touts as an advantage, since it makes the scheme more palatable to capitalists by reducing the overall cost of emissions reductions) when the most important task is to wean the developed world off fossil fuels. Daniel Tanuro, writing in International Viewpoint, deepens this critique, arguing that precisely because carbon markets are based on the quantitative principle of cost-effectiveness, they cannot drive the qualitative change we need to create a sustainable society. Carbon markets will favor mechanisms such as biofuel plantations, which are cost-effective in quantitative terms but are inconsistent with the energy revolution we need. Carbon trading points away from, not toward, an ecologically sustainable and socially just society.

Cap-and-trade for the people, or for the capitalists?

Hahnel calls critiques of carbon trading “ill-informed”, but he appears to be misreading them. These critiques are not targeting the ideal proposal for carbon trading that he presents—instead, these are critiques of the cap-and-trade schemes that have actually been proposed and implemented. These policies are in no way intended to challenge society’s reliance on fossil fuels. The experience of the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), the largest yet existing carbon trading system, neatly illustrates these critiques. It is well-documented that in the initial phase of the system, carbon credits were enormously overallocated, resulting in windfall profits to major polluters and a failure to actually cap emissions. Further, the ETS carbon market has been highly susceptible to false offsets, frauds and scams, resulting in a volatile and declining carbon price that fails to incentivize conversion to renewable energy. The result has been a system that, far from reducing carbon emissions, has reinforced a carbon-based economy by helping polluting industries avoid reducing emissions. The ETS is so bad that a group of European civil society organizations has given up on the possibility of reforming it, instead demanding that it be scrapped. Their declaration argues that it makes meaningful carbon reform even more difficult and provides a bad model to be exported around the world.

This is exactly what happened in 2009 when congressional Democrats proposed the American Clean Energy and Security Act (ACES). This bill would have implemented a national carbon trading system that would have repeated the failures of the ETS. Despite Obama’s campaign promise of a carbon trading system in which no permits would be given away for free, the bill would have given away 85% of the initial permits freely—again subsidizing polluters by giving them huge quantities of a tradable commodity (Chris Williams, Ecology and Socialism, p. 83). The bill allowed so many carbon offsets that it would not have met even the watered-down reduction standards it claimed—if polluters used the maximum number of offsets, emissions levels would not have dipped below 2005 levels until 2026. And this is assuming that the offsets purchased were real—most of them would have been international offsets, which are notorious for being fraudulent or altogether false (Williams, p. 83). ACES was not a proposal for dealing with climate change in any meaningful way—in fact, it might have made the situation even more difficult by instituting a “solution” that subsidized fossil-fuel companies while reinforcing North-South inequity through unfair international carbon offsets.

Hahnel is no doubt aware of the inadequacies of these cap-and-trade proposals. His proposal does not share these problems—rather, it’s based on social justice and climate science. I review the failures of carbon trading in the US and Europe in order to demonstrate that the cap-and-trade policies enacted by capitalist governments have exactly the opposite basis. Their purpose is to provide the appearance of doing something while, in fact, fending off a challenge to capitalism by permitting a fossil-fuel-based economy to continue for as long as possible, and, to the extent that transition from fossil fuels does occur, placing as much of the cost as possible on the working class and the developing world. These schemes, not Hahnel’s proposal, are what left critics of carbon trading are responding to. These policies represent the capitalist class’ favored “solution” to the climate crisis, and as such are a real threat. As such, it’s very important for the left wing of the environmental movement to expose and critique these policies for what they are. I therefore disagree with Hahnel that the left wing of the environmental movement should in any way temper its criticism of cap-and-trade as it actually exists.

One popular critique of “cap-and-trade,” that addresses the “devil in the details” of the plan.

How do we win reforms?

Of course, critique is only part of our task as ecosocialists. We also aim to win—to fend off ruling-class attacks, to win reforms, and, ultimately, to overthrow capitalism and replace it with an ecosocialist system. I agree with Hahnel that we must win meaningful climate reforms soon in order to avoid catastrophe. I disagree, however, about how we can win reforms. Hahnel seems to be arguing that the best way to win reforms is through a reformist program and strategy—but I think the best way is a revolutionary strategy.

It appears to me that Hahnel’s understanding of how reforms are won suffers from an excessively black-and-white understanding of the dynamics of power in capitalism and socialism. This leads him to a constriction of political possibilities and ultimately to a reformist strategy. He writes that, although it’s clear that we need radical emissions reductions within ten years to avoid catastrophe, an ecosocialist revolution “is not going to happen in the next ten years because eco-socialism requires massive political support that cannot be won overnight.” Therefore, although “massive demonstrations and civil disobedience are desperately needed to overcome lethargy and catalyze needed political action,” those demonstrations must focus on a program that’s limited by the possibilities capitalism offers. Indeed, Hahnel even defines a program as “a set of policies that will achieve these results [radical emissions reductions] even while capitalism persists.”

It’s certainly true that there is a fundamental distinction between a capitalist and an ecosocialist society. In the former, the capitalist class is hegemonic, and uses its power over the economy to exploit workers and the planet to accumulate profit at the expense of life. In the latter, the working class and oppressed groups democratically control the economy in the interest of justice for all and ecological sustainability. This distinction has an obvious impact on the kinds of policies that can be implemented under either system.

But, although in a capitalist system the capitalist class is always in power, at no point is the relationship of forces between classes static. The working class, the capitalist class, and other social forces are always vying for power and influence within the system and its units—within workplaces, neighborhoods, and various levels of government, for example. Reforms, in general, happen when the working class or oppressed groups gain enough power to force the hand of the ruling class—putting them in the position of either implementing the reform or losing needed credibility and influence.

People fighting for liberation have many choices of strategies in their battle with the capitalist class. They may choose strategies based on accommodation to the class enemy and seeking a role within the current system. This strategy may provide reforms for as long as the capitalist class is prepared to grant them, but tends to lead to a decline in the power of the movement’s base and the political co-optation of the bureaucratic leadership, as has happened with the US trade union movement and the British Labour Party. Alternatively, they may choose strategies that are not confined to bourgeois frameworks and which build popular power independently from state institutions. We see this strategy in the great worker-led strike waves of US history, the Black Liberation movement, and, today, in the youth immigrant rights movement. This is a difficult road, but ultimately one that, if successful, is far more likely to lead to the shifts in consciousness and power relations necessary to win major reforms. It is also more likely to lead to the development of a revolutionary movement, as it invites those in struggle to think and act outside of the confines of capitalist ideology.

Principles, not policy

Such a strategy of class independence is what I refer to as a revolutionary strategy. A revolutionary strategy does not preclude struggle for reforms—indeed, most of the time, except in revolutionary situations, revolutionaries are engaged in reform struggles. The question is how to struggle for reforms in a revolutionary way. Obviously, the answer to this question differs situationally and has many aspects. Hahnel’s essay addresses the question of program, so that is the aspect I limit myself to here.

Unlike Hahnel, I conceive of program not as a wish-list of policies we’d like to see implemented, but as a tool of struggle. Through our ecosocialist program, we articulate the politics of the movements in which we are involved in a way that promotes solidarity and draws attention to the conflict between the movement and the capitalist system. We typically argue for stances that are further to the left of those in the mainstream of the movement, while posing them in a way that is relatable and responsive to the movement’s aims. We should think strategically about the politics we put forth in our movement work: what demands, what slogans, and what ideas will help the ecological movement grow, develop alliances, become more powerful, and radicalize?

This way of posing the question immediately suggests some answers. In general, our program should address immediate concerns of working-class people. It should draw connections between the fight against ecological destruction and the overcoming of racial, national, and gender- and sexuality-based oppression. It should uncompromisingly demand a shift away from fossil fuels, done in a way that meets human needs. Finally, all of these demands should be framed in ways which, as much as possible, point in the direction of the environmentally and socially just society we want to see, inviting people to think outside the confines of capitalism. Hahnel is absolutely right to demand a global emissions cap based on science that would be vigorously enforced for all countries. Here are some other possible elements of an ecosocialist program:

- A shift away from fossil-fuel and nuclear electricity production; a free basic energy allowance for all individuals

- Free, improved and expanded public transit in all major cities

- Retrofit housing with passive and active solar heating; provide good-quality housing for all through rehabbing abandoned buildings and sustainable new construction

- To produce goods mentioned above, retool shuttered factories, providing safe and well-paying jobs; retrain workers who lose jobs in polluting industries

- A 30-hour workweek with no loss in pay

- A moratorium on all new fossil-fuel extraction; clean up polluted communities and areas

- Dismantle the global US military; use the money saved for reparations for sustainable development to countries which have been subject to US imperialism

- Greater investment in parks, education, and other public goods

Someone who is better than I am at coming up with slogans can figure out how to popularize these demands, but you get the picture. Demands like these are designed with the goals of a revolutionary program in mind. They are best able to meet these goals when that they focus on principles, rather than on policy. A focus on policy—the legislative means by which the reforms we want will be enacted—limits our political imagination to what’s possible within the capitalist system and pulls our politics rightwards. Instead of asserting that another world is possible, we adapt our program to the assumptions of the capitalist system. Instead of choosing strategies and tactics that confront the state and the capitalist class, we begin to think in terms of what is possible (or “realistic”) under the present system, to view progressive bourgeois legislators as our allies, and to think in individual rather than collective terms—leading to a weakening of the movement. To build the power necessary to force the capitalist class to grant us concessions, we need to focus on the principles that unite us, not on policy. It is bourgeois legislators’ job to figure out how to implement those concessions within the framework of bourgeois policy—we should not do their jobs for them. Of course, if legislators do propose policies which could partially mitigate the problem, we should critically support those reforms. But it would be a step rightwards for the left wing of the movement to make a particular policy reform part of its program.

Such an approach actually helps us build the power necessary to win reforms now. The more people view the ecology movement as tied to those of workers and oppressed people by the possibility of a just society, the more those movements will be united. The more people view the state as standing on the side of our enemy rather than a neutral actor that needs to be convinced, the more likely they will be to choose tactics that pose a militant challenge to the state. The more people are able to imagine a future beyond capitalism, the more the ruling class will feel the need to implement reforms to shore up their position. I’m sure Hahnel agrees with me when I say that the climate crisis and other ecological problems are rooted in the structure capitalist system (not just a few sectors of capital, like the fossil-fuel industry, but the system itself), and cannot be reformed away. Our program and strategy should reflect that understanding.

What’s realistic?

Hahnel’s argument seems to be motivated for a desire for a radical proposal to prevent catastrophic climate change that appears realistic. This is an understandable impulse: the movements of workers and oppressed people are relatively weak, making a global ecosocialist revolutionary movement that has the power to win meaningful reforms within the time frame we have seem like a remote prospect. It makes sense to look for a way to reduce carbon emissions that can be implemented immediately However, I disagree that Hahnel’s proposal is realistic.

To his credit, Hahnel does not water down his proposal in order to make it palatable to the capitalist class and the politicians that serve them. He insists that a global cap-and-trade scheme would have mandatory emissions caps for all countries based on science, differential emissions caps based on principles of global justice, and enforcement mechanisms to prevent cheating and bogus carbon credits. It’s a principled proposal. The problem is that, in order to keep it principled, he must put so many conditions on cap-and-trade that it might as well be a revolutionary demand.

We have seen that the cap-and-trade proposals which capitalist governments have been willing to countenance have little in common with Hahnel’s proposal: they are deliberately full of loopholes, promote the accumulation of capital, and protect the dominance of the imperialist countries with their carbon-heavy economies over and against the developing world. The ruling class would never agree to a policy like Hahnel’s proposal, which would amount to voluntarily abandoning imperialism and agreeing to destroy huge sectors of highly profitable capital. They would have to be forced to do. It wouldn’t necessarily require a revolution, but it would require a volatile political situation in which a mass movement had the power and popular support to seriously challenge the legitimacy of capitalist governments. But in such a situation, we would be in a position not only to demand market-based reforms, but to put forward the possibility of “system change”. So why should we limit ourselves to demanding carbon trading? Socialists should not limit themselves to demands that are theoretically possible under capitalism—especially when those demands are no more realistic than revolution itself.

In the meantime, we certainly do need to demonstrate that there is an alternative to capitalism. One obstacle to a global ecosocialist movement is that there does not appear to be any concrete alternative. However, we can show that our radical demands are possible without resorting to policy proposals. For example, when someone asks us how we would pay for the expense of providing food, housing, and education for all in an ecologically sound way, we can point to the way capital manages social resources inefficiently, how it produces things nobody needs in unsustainable ways, and how the vast profits currently appropriated by a small elite could be redirected towards a transition away from fossil fuels.

Toward a revolutionary ecosocialist strategy

Hahnel is not alone in arguing that the urgency of the climate crisis merits a shift towards reformist politics. Christian Parenti argues a similar point in Dissent and in the current issue of New Politics. Compared with Hahnel’s argument, Parenti’s engages much more with the reality of present-day politics, but I believe he commits a similar mistake as Hahnel. I don’t have the space or resources here to fully reply to Parenti, but I generally agree with the response of the Monthly Review editors to Parenti’s Dissent piece:

A revolutionary approach in this area is one that does not simply stop with whatever limited reforms are easily conceivable within the present system, but also: (1) seeks to accelerate the shift to a substantively equal and ecologically sustainable (global) society; (2) involves the mobilization of the entire population (and entire peoples), culturally, socially, and economically in the process of transformation; (3) prioritizes conservation of human and natural resources; (4) seeks to transform infrastructure and technology on a massive, democratically planned basis to meet ecological and social ends; and (5) opposes the logic of profit-making at every point along the line, substituting the alternative logic of people and the planet.

These principles may sound vague. Indeed, both Hahnel’s and Parenti’s arguments seem to be based on a judgment that revolutionary ideas are too abstract to offer guidance in this time of acute ecological crisis. Hahnel writes, “But unlike some in the climate justice movement I will not confuse good slogans and chants with a political program to prevent climate change,” and Parenti states, “I know this doesn’t sound revolutionary or radical, but what I’m trying to do is to be very, very realistic. Because I don’t think it is sufficient to be outraged about this and invoke the righteousness of our cause.”

There is truth to this. No manifesto, no strategic document that fully outlines an ecosocialist strategy has yet been produced. Much writing on ecosocialist politics and strategy has been quite abstract. For example, above I suggest elements of an ecosocialist program, but I do not translate them into accessible slogans or suggest settings in which to raise these demands. The problem is that translating ecosocialist principles into a strategy can only be done through experience, and the ecosocialist movement is in its infancy. We need further engagement of ecosocialists in the developing struggle and ongoing discussion of the lessons of that experience in order to concretize our strategy.

Fortunately, ecosocialism is growing as an organized left force. Within the past year, ecosocialist coalitions have formed around the world, including Reseau Ecosocialiste in Quebec, the European Ecosocialist Action Network and European Ecosocialist Conference, and the US-based System Change Not Climate Change: The Ecosocialist Coalition. These organizations share a commitment to ongoing, democratic political discussion linked with an engagement in struggle. Their growth reflects both the need for and the appeal of revolutionary ideas in a world beset with crisis. The experience of these and other efforts will be the basis for crafting a revolutionary ecosocialist strategy for the 21st century.

Nicholas Davenport is an environmental activist in Baltimore and a member of System Change Not Climate Change as well as Solidarity’s Ecosocialist Working Group. This article was originally published by New Politics.

Comments

2 responses to “Time to Adopt “Cap-and-Trade”? A Response to Robin Hahnel”