by Ellis Boal

January 30, 2014

This article was originally published by Global Frac News. We republish it here with a new interview conducted by the editors of this website.

Solidarity Webzine: Your article reports on an important legal victory against fracking. For our readers who may not know much about fracking, could you explain briefly what it is and the problems it causes?

Ellis Boal: “Fracking” — an industry term — is short for “hydraulic fracturing.” In its most alarming form these days fracking is done in wells which have been drilled first vertically, and then after a right-angle turn at the depths, horizontally. The vertical and horizontal legs can each be two miles or more in length. Wells in Michigan are that big.

In fracking, a slurry of water, sand, and chemicals is pumped down at very high pressure to create fractures or expand natural fractures found in the rock. The slurry may sum to millions of gallons, 31½ million in three of the 13 Department of Environmental Quality-approved wells which were just enjoined here. The purpose of the sand is to hold open the fractures once they are created and the water pressure relieved — in effect making impermeable rock permeable.

The chemicals used may vary from one well to the next, and have a variety of different purposes (for instance, to reduce friction or to kill organisms which live at the depths). Some which are frequently used are carcinogenic or are endocrine disrupters. Some have ingredients which the industry refuses to disclose on the ground they are trade secrets. One with a secret ingredient used in Michigan — called “acid inhibitor 2” — is a flammable liquid and vapor, which may explode or flash back from a source of ignition, according to the manufacturer. It is fatal if swallowed and may be fatal if inhaled.

There are a variety of other harmful side effects of fracking too, including dangers in the “plowback” material that comes back up and in the disposal of that material.

Once the fracking process is done the well can start producing. Propped open by the sand, the fractures expose surface area, allowing gas to flow into and up the wellbore under its own pressure. In Michigan fracking is done primarily for natural gas. In other states such as North Dakota it is done for oil. One of the problems with gas — a problem aggravated by the fracking process but still a problem even with non-fracked gas — is that some inevitably escapes to the air unburned, either at the wellhead or in the pipelines some of which are decades old. Most of the gas is methane, a tremendously destructive greenhouse gas.

Most people consider the threat to underground water sources as the most important drawback of fracking. I consider the threat to climate to be greater.

S: You won an injunction against Encana Corporation. What exactly did you win? How likely is it to hold? It is clearly an important symbolic victory, at least–is it more than that too?

E: The process is slanted in favor of tracking well operators; it is a two step process and Encana can appeal to the second step if it loses but Brady can’t if he loses. The judge sent Brady into the process anyway. But at the same time the judge understood that once Encana starts to drill there is no going back. So he enjoined the wells till the process is over and Brady has a chance to come back to court. That would probably be this summer. The chances of the injunction becoming permanent? As the article says, not bad if Brady handles himself well in the hearing. But even if he wins, the company can re-apply and provide good data to show non-interference. That is, provide good data if it has any. It didn’t try to produce the data in court. Even if it does have data, the wellheads would still have to be separated by 660 feet. That requirement might induce the company to pack up and go away.

Meanwhile a separate problem has arisen. The DEQ is now proposing new rules which could go into effect this year after a public hearing. The new rules would eliminate the requirements of 660-foot surface separation and proof of non-interference. But even if new rules go into effect, the judge has power to insist on the old rules.

S: As you say in your article, “court battles based on regulations cannot prevent the onslaught.” What could prevent it?

E: A “people’s injunction” — or an initiative — as described below. The wording of our initiative would ban horizontal fracking and storage of frack waste in the state, and repeal the state’s 75-year-old statute requiring DEQ regulators to “foster” the oil-gas industry “favorably,” and to “maximize” oil-gas production. Maximizing production maximizes oil-gas profits as well as Michigan’s contribution to global warming. For the exact language of our measure, see the Let’s Ban Fracking website.

S: You refer readers to the letsbanfracking.org website to help win a “people’s injunction” against fracking through a referendum. What would the initiative do? How likely is it to succeed?

E: Not every state constitution gives citizens the initiative power. But Michigan’s does, a result of progressive-populist agitation the early 20th century. Our constitution says if we get a certain percentage of the voters to sign petitions for a measure, it must go on the ballot for an up-or-down vote. This year the percentage works out to 258,000 signatures, which have to be verified by state canvassers. Before going on the ballot the legislature gets a chance to enact it without need for an election. The legislature can also put a conflicting measure on the same subject on the ballot. Or it can take no action, which then automatically places our measure on the ballot.

If voters put a ban into effect the governor cannot veto it, and the legislature cannot repeal it except by a 3/4 vote of both houses. In Michigan, unlike in Vermont, New York, and New Jersey, the legislature — both Republicans and Democrats — have no stomach for a frack ban. Just the opposite. Almost all of them are for increasing gas production. But polls in Michigan and regionally are showing a shift in our direction. See here and here.

S: How do injunctions and referenda fit in with other strategies activists are pursuing, including direct action, mass demonstrations, and trying to mobilize unions and community groups? Are there any organizations working to build resistance to tracking in your area, or attempts to build such organizations?

E: There is but little direct action in Michigan. I wish it were otherwise.

S: What do you think are the next steps, or how do you plan to follow up on this legal victory and push the advantage?

E: What the legal victory did was embarrass Encana and the DEQ, as well as give some breathing space for people in Kalkaska County. Other suits are in the works which could produce similar results. The main task now is the ballot initiative. It got 30,000 signatures in 2012, and 70,000 in 2013, using an almost- all-volunteer force of over 500 petitioners. The industry took us seriously. The state chamber of commerce mounted a billboard campaign against the initiative, collecting $425,000 from the industry according to state records. We have to start over again each year; signatures must be collected in a 180-day period. We will collect in 2015 for the 2016 ballot. This time we are fundraising to hire paid circulators. We have found paid collectors can do a better job.

* * * * *

A state court judge ordered an injunction in October against Encana Corporation, stopping eight big horizontal frack wells in Kalkaska County, Michigan. The injunction was later extended to five more wells. An administrative hearing is to follow, conducted by the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), the agency which had permitted the wells.

The order, signed by Judge Clinton Canady III on November 13, held Encana “shall not commence drilling operations” pending the administrative hearing.

They would have been deep shale wells, four miles in measured (vertical + horizontal) depth, in Michigan’s Utica-Collingwood layer.

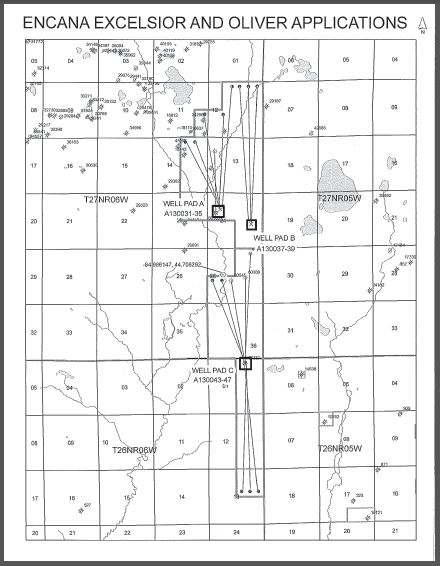

Encana plat of proposed 2013 development, showing 4 existing wells and 13 proposed new wells, on well pads A, B, and C.

The suit, brought by nearby landowner Paul Brady under the state’s environmental protection act, highlighted two violations of Michigan regulations: 660-foot surface spacing required between adjacent wells, and the DEQ’s failure to investigate the possibility that fractures from the wellbores might interfere with each other underground.

Encana, a Canadian corporation with worldwide assets, has capitalization of US$14 billion. At $8 million each, the company would have spent over $100 million on the 13 wells.

Encana’s applications estimate that the 13 wells together would use 387,660,000 gallons of water for fracking.

Three of the wells are in Oliver Township on pad C (see above plat). At 31,500,000 gallons of water each, Brady declared in an affidavit they would be the largest frack wells he knew of in the world. Recently a larger Encana well in British Columbia’s Horn River Basin was noted, at 45 million gallons. The Oliver wells would set merely a US record.

The cited regulations apply to all wells, vertical or horizontal, when an operator seeks a “spacing exception.”

Administrative regulations — sometimes also called “rules” — are enacted by state agencies after public hearings, a process less formal than that used by the elected Michigan legislature for enacting statutes. Typically statutes reflect broad social policy while regulations are more detailed and technical. Once enacted, an administrative regulation or rule has the force of law unless overruled by a court.

Violation of the 660-foot rule was apparent on the face of the DEQ permits. The 13 wells were to be on three pads along Sunset Trail in Excelsior and Oliver Townships. Platted surface separation of the wellheads proved to be far below the limit: 50 to 55 feet.

But proof of DEQ failure to investigate interference was problematic. It was uncovered by a request last summer under Michigan’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) by Ban Michigan Fracking (BMF) for information about the permits. DEQ refused at first. BMF threatened a separate suit and sanctions. DEQ relented and said BMF could have it, but for $516. BMF narrowed the request to include only documents about the spacing exception. Finally 396 pages of FOIA documents arrived, for free.

Brady filed the pages and cited them in his affidavit. None show DEQ examination or discussion of any data on the interference issue. This nailed the case.

The two regulations

What is the reason for the regulations?

- As to spacing, Cornell University’s fracture mechanic engineer Anthony Ingraffea says disturbance of young cement due to adjacent drilling activities on the same pad is a key negative influence on well structure integrity. The city of Dallas Texas recently adopted a 1500-foot setback requirement between wells.

- As to interference — also called communication or a frack hit — fractures can travel over a milecreating a channel between adjacent wellbores. Communication through the fractures can result in spills and environmental problems at the surface. Brady cited the following:

- Encana frack operations in New Mexico last fall blew out an old producing well a half-mile away. Two hundred barrels of oil and wastewater went onto the ground.

- An oil well being fracked in Alberta in 2012 caused a geyser of oil and frack fluid in another well 3900 feet away. Twenty thousand gallons of oil and frack fluid went on a farmer’s field, coating 100 trees with a fine mist.

The Excelsior-Oliver well sites are in pristine woods of the Père Marquette State Forest, an area frequented by hunters, hikers, and snowmobilers. Brady has a young family. He lives 2-3 miles from the involved wellpads and frequently snowmobiles by them. The endpoint of one well was to be a half-mile from the main buildings and lake of the Boy Scouts’ 1200-acre Camp Tapico. The Cranberry Lake boat launch and the North Branch of the Manistee River are nearby.

When Encana applied for the 13 wells it claimed the wellbores would be “at least 900 feet apart.” This proved to be false. BMF’s FOIA documents contained reports called “anticollision” reports. They show the geometry and distances between wellbores (not between fractures). These reports showed the maximum “distance between centers” for two of the wellbores was 854 feet, at least 45 feet less than what Encana said. Similar discrepancies were found for the other wellbores.

Encana makes corporate presentations every month for investors. It has its eye on Michigan. Early in 2013 the presentations highlighted the company’s 429,000+ net acres and 500+ well locations in Michigan’s Utica-Collingwood play. The play covered most of the state’s northern lower peninsula.

In January 2013 the presentation listed the play’s number of well locations even higher, at over 1700.

Encana arguments

DEQ did not oppose the injunction. But Encana did. Here were its arguments:

- First, the company attacked Brady, saying he had no real interest in the case. The possibility he might be injured due to a blowout as he went by on a snowmobile, or that he might have to slosh through thousands of gallons of frack fluid on the forest floor, or that he might have to see the trees coated with a fine mist — none of these were environmental issues, the company brief said: Permits for wells which are too close and might communicate “cannot harm the environment.”

- When Encana applied for the wells it claimed that data from three nearby comparator wells (pictured here, here, and here) fracked in 2011, proved that underground interference was impossible. But it never actually gave DEQ data from the 2011 comparators. Even if it had, the comparators were not as deep as the 13 new wells and there were no wellbores nearby at the time they were fracked. No promise was made to frack the 13 at the same or lower pressure as the three comparators. When it came to court the company shifted the explanation. It provided one-page “well completion” records for two different wells fracked in 2012 on the same pad as one of the three comparators, and said the two had had “no detrimental effect” on the one. But the 2012 completion records had no technical microseismic, tiltmeter, or streaming pressure data. There was no 3-dimensional diagram or map of the fracture planning zone. The records did not state distances between the wellbores. They said nothing at all about interference. So which was it, three comparators or two? Shifting explanations are evidence of lying. And even if there were no accidents in 2012, at most this shows Encana was lucky at one pad. Moreover, the applications for the 2012 wells had cited the same three 2011 comparators, and similar to the 13 wells at issue for Brady, they provided no actual microseismic or other hard data. Had he started the suit a year earlier the two 2012 wells could have been enjoined too.

- Though the regulation explicitly defines the “location” of a well as measured at the earth’s surface, Encana asked the court to measure spacing at the level of the bores’ 2-mile deep “productive” portion. Current Michigan regulations do not even define that term.

- Encana claimed that DEQ has a good record since 1952 regulating 12,000 frack wells in the state. But it ignored that the great majority of the historic wells were vertical, not horizontal, and they typically used only 50,000 gallons of water. This is a sixth of a percent of what Encana planned for the huge wells on pad C. Stated otherwise, the 13 wells at issue in the case would use as much water as 7,753 of the traditional vertical wells. The DEQ’s past record with small vertical wells is irrelevant to whether it has the ability to control the beasts Encana was planning for Sunset Trail.

- It claimed that if Brady’s case succeeded the end result would be an increase in the number of wellpads and forest impact, contrary to the environmental interests he purports to assert. But equally, the result could be Encana will not drill at all, because of the expense of siting so many wells on separate pads.

Encana’s 2012 wells, under construction on well pad C. Photos: LuAnne Kozma.

On October 25, five days before Judge Canady’s announcement, Encana applied for two additional nearby wells in Oliver Township. On November 14, two weeks after the hearing, it withdrew those applications.

DEQ precedent

The case established a legal precedent. In three of its court briefs the DEQ said:

A party that seeks to challenge the DEQ’s decision to issue any permit under [the oil and gas law] has the right to challenge that decision administratively.

There is a Michigan statute which allows administrative appeals of permits, but the statute only allows a producer or owner to invoke it. An “owner” means a mineral owner, which Brady isn’t. However the DEQ brief was not referring to that statute. It was referring to “part 12” of its administrative rules for oil and gas operations.

Encana supported DEQ’s reasoning (and made no objection to Brady’s administrative standing). Judge Canady agreed with both of them.

The surprise result is a member of the public can force a part 12 hearing over any well. No Michigan court has ordered or allowed a permit-objector into part 12 before.

At first glance the ruling looks like an empowering win for citizen activists. Part 12 hearings are under Michigan’s Administrative Procedure Act (APA) with discovery and subpoena power. APA hearings must be conducted in an “impartial” manner. They are open to the public. Unlike in a court, the objecting party need not hire a lawyer. The proceedings typically take a year or more. In the meantime the objector can find something improper in the permitting process and get a court injunction.

What is important about the principle is that the DEQ stated it, not just that Judge Canady agreed. When another permit case arises the DEQ has to be consistent and say the same thing.

This is interesting because last summer a governor-approved fracking assessment by the Graham Institute at the University of Michigan said the opposite. It said ordinary citizens have no right to intervene while a permit application is pending. In a detailed policy/law technical report, one of a series on fracking, it wrote:

Unlike many environmental permitting programs, oil and gas well programs do not historically give the general public the formal opportunity to review and comment on permit applications, or require agencies to respond to comments…. Michigan law gives local governments the opportunity to comment, but not the general public…..

This gave the deflating impression that Michigan law gives citizens no power. The head of the DEQ’s Office of Oil, Gas, and Minerals, Hal Fitch, sat on the Graham assessment steering committee and met with the report author before this passage was written. Presumably he endorsed it.

It’s true citizens have no power, but not just for the reason in the Graham report, which took no notice of part 12 in relation to permits.

Administrative hearings under part 12

Consider the specifics of part 12:

Its stated purpose is to “receive evidence pertaining to the need or desirability of an action or an order” of the DEQ. Hearings are conducted under APA standards. The APA covers both rulemaking and contested cases. Receiving evidence about the need or desirability of an action is a rulemaking procedure, not a procedure to resolve a contested case. In fact, part 12 makes no mention of contested cases. Commonly it is used to decide whether compulsory pooling is necessary over a mineral owner’s objection. DEQ does have a different set of rules for deciding contested cases, but by its terms this set does not apply to oil or gas permits.

Nothing in part 12 prescribes when it may be invoked. The desirability of a permit application which has not yet been granted fits part 12′s wording perfectly. Accordingly if part 12 applies to permits at all, Brady need not have waited. He could have started the hearing process while Encana’s permit applications were pending.

Part 12 is expensive, cumbersome, and industry-oriented. Brady argued that Judge Canady should not send him there:

- DEQ will itself be the decider of the “need or desirability” of wells it already approved. The proceeding can hardly be termed “impartial.”

- “Need or desirability” of a permit is not the same as the question whether it complies with existing regulations. Compliance is the standard DEQ is supposed to use to grant or deny a permit. Two different standards means there is a moving target, which the industry knows how to exploit.

- One of the part 12 rules says objectors have to submit well production, testing history, and reservoir and geological data when they start the proceeding. A nearby landowner typically has no interest in that kind of information, or access to it without trespassing or hiring an expensive expert. For industry people on the other hand it is their stock in trade.

- Part 12 says the objector has to front substantial funds for a legal notice in a trade publication. Industry-controlled Michigan Oil & Gas News is the only such publication in the state. It charges $22/column inch. The MOGN publisher has the right to refuse a legal notice from someone like Brady who does not subscribe, according to an affidavit in the case. MOGN’s refusal would abort Brady’s hearing. Part 12 says he must also pay to publish the notice separately in a general newspaper.

- The hearing will be a waste of time. Brady’s evidence is expected to include the incriminating plat and FOIA documents which are already in the court record. Encana’s evidence will be its one-page “good-luck” completion records (see above), also already filed in court. It cannot retroactively present new evidence in support of a permit already issued.

- A part 12 hearing has two steps. According to the rules Encana can appeal to the second step if it loses at the first because it is an “owner or producer.” As a non-owner non-producer, Brady does not enjoy that right. If somehow he were granted the right anyway, he would have to pay for expensive new legal notices in the newspapers.

Given the problems with part 12, Brady might find himself back in court sooner than anyone thinks.

A Democratic bill was introduced in the Michigan House in 2013 under which interested people would be able to get a public hearing and have comments considered before a well permit is issued. The precedent established by DEQ in this case means a part 12 hearing requirement is already the law, though the procedures are different than those contemplated by the bill.

DEQ surrender

DEQ had an explicit duty under the regulations to examine and judge interference data. It had an explicit duty to prohibit wells closer than 660 feet. Why did it suck up to the company instead? This was like a guard giving a prisoner the keys and saying “Let yourself out when your term is over.”

The answer does not lie in corruption, intimidation, negligence, or incompetence.

On November 1, two days after Judge Canady’s hearing, DEQ published several regulation revisions it is planning to implement in 2014. The particular regulation in Brady is R 324.303(2). The planned revision of this rule will jettison the spacing-exception requirement of 660-foot spacing and review of interference data.

A public announcement of regulatory changes and public hearings had been made on October 22 before the court hearing. The announcement summarized changes which would be made only on other subjects. After the hearing was when DEQ revealed it was targeting the spacing and interference requirements.

This tells us the decision not to examine Encana interference was deliberate, a pre-figuring of what DEQ was already planning without telling anyone.

The only justification for such an end run would be the state’s policy — legislated into statute in 1939 — requiring DEQ regulators to “foster” the oil-gas industry “along the most favorable conditions” and to “maximize” oil-gas production.

Encana and the Canadian frack industry generally claim to take the issue of well communication seriously. According to voluntary best practices in Canada, interwellbore communication can lead to unintended surface or subsurface flow, or a blowout. To prevent that, frack operators delineate a fracture planning zone. The zone must be based on an estimate of the maximum predicted fracture distance or influence. The number is then doubled. Every other well within that radius is then identified and evaluated for risk methodically.

Michigan doesn’t have anything like that even on a voluntary basis, and now the plan is to reduce what little it does have to zero.

The governor-approved Graham policy/law report ignored the whole issue.

The DEQ proposed a second under-the-radar rule change in November. It would permit an operator to drill and frack in a unit that is not totally leased or pooled if the operator claims a “good faith” effort was made to obtain voluntary consent from mineral owners. When production is ready to start the operator can then start a part 12 proceeding to compulsorily pool the unit. Like building the gallows before holding the trial, this is to intimidate hold-outs, including environmental hold-outs. To soften the blow, the term “compulsory pooling” will be changed to “statutory pooling.”

After the hearing

Ordinarily a judge will not order an administrative hearing if it would be a fruitless task due to the result being forgone. But this is what happened here. The end result of the hearing is already written on the wall. Fortunately, when the process ends the injunction will stay in effect for 30 more days, to allow Brady to come back to court.

Under Michigan’s environmental protection act, even after a loss in the administrative hearing and even with a new emasculated regulation, Judge Canady has power to reject the hearing result and apply the old standards. He can hold that Encana has to prove its case if it wants the wells. He can hold a showing of past good luck is not sufficient.

One alternative, always open to Encana on the interference issue since Brady started the case last June, was to withdraw its applications and file new ones, spoonfeeding the DEQ complete, rigorous, and truthful data. Meanwhile if the proposed new DEQ spacing regulations go through in 2014 and the company gets around the judge, it could have a clear path on that issue as well. The result would be uncontested permits, and a threat to the enjoyment of hunters, hikers, snowmobilers, and Scouts in the state forest.

One reason why the company didn’t re-apply and produce good interference data could be the data just doesn’t exist. All Encana has shown are the one-page completion reports from two lucky wells, and those two shouldn’t have been permitted either.

As mentioned, the company has its sights on a large swath of northern Michigan. As also mentioned, the state’s policy at least for now, is that oil and gas are state-favored special interests.

A Michigan citizen temporarily did put on the brakes. Only time will tell if the injunction holds. Even if it does, Encana still has hundreds more places to try.

Michigan is under threat by many operators in addition to Encana. Court battles based on regulations cannot prevent the onslaught. Far-thinking activists in Michigan are seeking a “people’s injunction” — a permanent statewide ban of horizontal fracking. Go here to help.

Legal Filings

Affidavit of Paul Brady — 10/23/13

Affidavit of Ellis Boal — 10/23/13

Second Affidavit of Ellis Boal — 10/30/13

Order — 11/13/13

Ellis Boal is a lawyer in Charlevoix, Michigan, and a Solidarity member.