by Dan La Botz

October 16, 2012

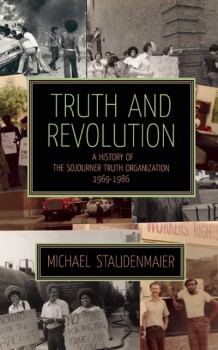

Michael Staudenmaier’s Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, recently published by the radical AK Press, is a thoroughly engaging critical history of one of the most interesting revolutionary socialist groups that emerged from the radical upsurge of the 1960s and 1970s. While Staudenmaier clearly admires STO, many of whose members he knew and several of whom were his friends, this is far from being a hagiographic work. The author presents the group with all its foibles, it many frustrations and its ultimate failures, without ever letting us forget that what he admires about this group was its attempt to develop socialist theory while also being deeply committed to organizing and struggle. It is not surprising that this book is being widely read by many of the new non-state socialist groups such as Advance the Struggle and the Black Orchid Collective that have arisen out of the social movements of the last decade and become visible through their work in the Occupy movement, for today they are striving to establish a theory and practice just as STO did—-and just as many other groups from a full range of left perspectives did-—in the 1970s. While there are now a pile of books about the party-building efforts of the 1960s and 70s, Staudenmaier’s is the most interesting one I’ve encountered.[1]

Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, 1969-1986

By Michael Staudenmaier

Oakland: AK Press, 2012

Paperback, $19.95

Perhaps I like this book so much in part because I lived in Chicago in the 1970s and knew a few of the STO members and always liked them. I was a member of the International Socialists (IS) and some of our members worked in the International Harvester tractor plant with some STO members and our two groups often collaborated, and sometimes differed, on workplace and community issues that arose there. Though STO formed part of the New Communist Movement and the IS had come out of the Trotskyist tradition, our groups overlapped in many of our political positions and in our work. We shared not only labor and community organizing experiences, but also found ourselves over the years involved in the same movements for international solidarity with the initial revolution in Iran in 1979 and with the Central American national liberation movements of the 1980s, and we shared preoccupations with the issues of African American struggles for civil rights and social justice and women’s fights for equality and liberation. Like STO, we in the IS wrestled with the problems that arise in a political organization from young people’s passionate personal relationships, with the issue of parenting and childcare, with the problems of leadership “heavies” who often seemed to make decisions without adequate consultation with the ranks. I think that anyone who was active in the left of the 1970s in almost any group would recognize themselves in parts of the STO story, and that new groups arising today will profit from Staudenmaier’s thoughtful examination of STO’s history.

STO’s Theory

The Sojourner Truth Organization was founded in Chicago in 1969 and Chicago remained its headquarters throughout its history, though in the 1970s and 80s the name was also applied to a network of organizations in cities mostly in the Midwest affiliated with and largely led by STO in Chicago. Several initial founders, who remained its leaders throughout most of its history, came out of Communist Party backgrounds. Don Hamerquist had been an outstanding young leader of the Communist Party who some believed would succeed its longtime chairman Gus Hall, but after attempting “to lead a coup in the party” and failing, he quit. Noel Ignatin (later known as Noel Ignatiev) had also been a Communist, but had left the CP with Ted Allen and Harry Haywood to found the Provisional Organizing Committee to Reconstitute the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (the POC). Carol Travis was the daughter of Bud Travis, a Communist Party leader in the seizure and occupation of the General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan, by autoworkers in the strike of 1936-37. Many of the STO founders had also been members of Students for a Democratic Society (sds) and one had been a member of the Black Panthers. While STO formed part of the New Communist Movement, largely made up of Maoist organizations, it was from early on influenced by the C.L.R. James who had come out of the Trotskyist tradition. Then too, Ken Lawrence had come out of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) experience, and brought the syndicalist idea into the group. Though its initial founding core had one African American and one Latina woman, both soon left the group and throughout most of its history STO was an all white organization.

What STO’s founding members had in common was a desire to build what they understood to be a Leninist organization based on independent workplace organizing and a belief that to do so they would have to challenge the racism of white workers. The notion of the importance of organizing workers had its roots in Marx and Lenin, but it had taken on a new sense of urgency and possibility as a result of the May-June strike in Paris in 1968, the “hot autumn” of strikes in Italy in 1969, and the massive strike wave in the United States in 1970. Unlike other groups in the New Communist Movement, the International Socialists, the Maoist “parties,” and other groups that had gone into the workplace to build rank-and-file or reform caucuses within the unions, STO argued that it was necessary to build completely “independent workers’ organizations” that would not be part of unions and would not contest to control union structures and offices. The theory of independent workers’ organizations (or workers councils as they were sometimes called), principally crafted by Don Hamerquist, was one of the two distinctive theoretical and strategic ideas developed by STO.

The other idea that STO developed and popularized was “white skin privilege,” a theory first suggested by Noel Ignatin and Ted Allen (not an STO member) in a paper called “The White Blindspot” originally written for a debate in sds in 1967. (Actually Allen had used the term in 1965 in a piece commemorating John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry; the kernel of the idea came from W.E.B. DuBois Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880.) White supremacy, they argued, was largely founded on white skin privilege, a set of real social and material benefits that accrued to those deemed to be white, from preferential treatment by government and police to first hired and last fired in the workplace. White skin privilege was seen as the principal obstacle to unity between black and white workers. STO argued that in the course of labor and social struggles, whites would have to repudiate their white skin privileges and show support for the struggles of African Americans and Latinos, and that by doing so, unity between white workers and workers of color would make possible a united proletarian struggle to overthrow capitalism.

Hamerquist, who helped to develop these theories about white workers’ racism and about the nature of the union, brought in the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci whose then recently translated Prison Notebooks used the concept of “hegemony” rather than simply the state’s monopoly of force to explain bourgeois rule. (Gramsci later became enormously popular among leaders of the more social democratic New Left, who used his concept of hegemony and the “war of position” rather than a “war of maneuver” to justify their turn to the Democratic Party. Gramsci also became enormously popular in academia where his writings were used for cultural studies rather than cultural or social revolution.)

Hamerquist argued that bourgeois hegemony was exercised over the working class through the labor bureaucracy and through white racism. He developed the concept of “dual consciousness” (not to be confused with W.E.B. DuBois’ use of that term), meaning that workers tended to have in their minds a bourgeois and a proletarian consciousness, and the job of revolutionaries was to help them in strengthening their proletarian consciousness. (In the political tradition from which I come, we never had such a Manichaean notion of workers’ consciousness, but tended to recognize that most people of whatever class have a “mixed consciousness”—-our minds made up of residues of beliefs and concepts from our family, religious training, grammar school education, the world of teenage peers, the bombardment from commercial advertising, and politicians’ appeals to patriotism—-the challenge being to come to think clearly about the world so that they can make intelligent choices for a revolutionary alternative.)

While independent workers’ organizations and white skin privilege were the two key ideas that distinguished the STO from other left organizations, during the 1970s and into the 1980s, the group also developed other positions that differentiated it from the New Communist milieu out of which it had come. During the 1970s Hamerquist and Ignatin wrote important documents breaking with Stalinism: they repudiated Stalin, they rejected the notion that Khrushchev or his successors had reformed the Soviet Union, and they rejected the idea that China or Cuba were socialist states, arguing that all were state capitalist. No doubt the influence of C.L.R. James had been important in leading them to this conclusion. They also rejected the Stalinist forms of party organization, arguing that most of what the left called Leninism were actually undemocratic structures and practices that would better be called Stalinism.

Finally, STO had throughout its history a very healthy concern about the relationship between a cadre organization or a political tendency attempting to build a revolutionary party and the movements, usually small but sometimes mass movements, in which it worked. Later in the 1970s and early 80s, STO would characterize this question between what we call in my tradition the issue of “party and class” as the issue of “autonomy.” This notion of autonomy is perhaps what Staudenmaier values most in the STO experience, though as he would be the first to admit, nowhere did the group succeed in either adequately explaining the theory or in working it out in practice. Autonomy was for STO, as it has been the other groups on the left, a slippery concept expressing the high ideal of freedom of thought and action for a social group, but constantly entangled in the questions of organizational structure, leadership, and program.

C.L.R. James: “This independent Negro movement is able to intervene with terrific force upon the general social and political life of the nation, despite the fact that it is waged under the banner of democratic rights … [and] is able to exercise a powerful influence upon the revolutionary proletariat, that it has got a great contribution to make to the development of the proletariat in the United States, and that it is in itself a constituent part of the struggle for socialism.” (Revolutionary Answer, 1948)

Workplace Organizing

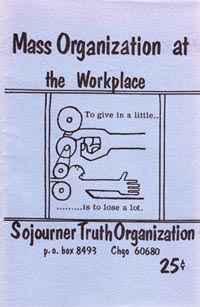

Staudenmaier provides a useful chronology of the STO’s activities: from 1969-1975, workplace organizing; from 1976-1980, anti-imperialist solidarity; from 1980-1986, tendency building and direct action. During the first period of workplace organizing, STO grew to fifty members in the Chicago area, many of those members engaged in organizing in factories in Chicago and for a while in steel mills in Gary, Indiana. In those workplaces STO often put out factory bulletins with names like Talk Back and Breakout! as well as its newspaper Insurgent Worker. STO, and the several lawyers in the group, also became involved in assisting workers in plants where it did not have members. While STO was sometimes involved in heroic and inspiring struggles, as Staudenmaier’s account makes clear, the group’s labor organizing activities seldom led to the formation of stable groups in workplaces. In part this was due to STO’s refusal to run for union office—though it did sometimes tacitly support reform candidates in the unions.

Though many STO members were in unionized workplaces, the union was not an arena of struggle for the group and consequently it could not turn its workplace struggles into institutional victories that might have changed the character of the unions. This problem was exacerbated by the fact that in many of the larger workplaces in Chicago, such as the Stewart-Warner plant, STO was only one of several left groups—-from the Communist Party to the New American Movement from Maoists to Trotskyists-—that had organizers in the plant, often with their own bulletins and newspaper. STO’s refusal to permit its members to run for office led to splits in the organization, as several of its best organizers, such as its leaders of the Latino caucus at the International Harvester plant, left the organization. Nowhere did STO succeed in creating the independent workers’ organization which stood at the center of its political theory.

All of the revolutionary socialist groups on the left in the 1970s were attempting to build a revolutionary party out of their work in industrial workplaces. The STO experience might be compared to that of other leftist groups, mostly Maoists, that ran their members for election as union steward, built local union caucuses, and participated in broader union movements, such as Steelworkers Fight Back, a caucus that supported Ed Sadlowski’s campaign for president of the United Steel Workers (USW) in 1977. Local union and national campaigns gave activists an opportunity to talk not only about shop floor issues, but also about the large issues facing the union, the industry and the society. When workers found their shop floor work had an impact on union policy and relations to the employer, they achieved power, as well as a greater sense of their own power, and often also improved their wages, working conditions, and benefits.

The most successful among the left organizations in such union work was IS, which was involved in initiating such caucuses in the United Auto Workers, the Communications Workers of America, as well as participating in such caucuses in the American Federation of Teachers and the USW. Most significant of these experiences was the IS’s role in establishing Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), a long standing caucus in the Teamsters union.[2] The IS also initiated Labor Notes, the union reform newspaper and education center with biannual conventions that attract a thousand union activists each year. While the IS initiated these projects, they were never conceived of as socialist projects and from the beginning were independent (autonomous) organizations with their own leadership, organization and resources, and programs. The collapse of the social movements of the 1970s (among African Americans, Latinos, women and students) and the end of the recent period of labor militancy with the recessions of 1974-75 and 1979-80, accompanied by the country’s right-wing administration under Ronald Reagan and depoliticization of the society, made the task of relating labor work to socialist ideas and organization a challenge for all of those on the left, with no simple answers.

Throughout that first five years of labor organizing, STO had constant interactions with African American and Latino workers and leftists, but its white skin privilege theory proved of little use in building alliances between white workers and workers of color, and STO could never decide if it should recruit people of color to their own organization, or urge them to join an African American or Latino socialist group. STO literature often challenged white workers to give up their white skin privilege and to support the demands of African American and Latino workers, but in practice it was not always clear what this would actually mean. Most other left groups viewed STO’s white skin privilege theory as liberal and moralistic; in any case, it proved no guide to action. Based on Staudenmaier’s account, African American and Latino organizations and leaders appear to have been mystified by STO’s theory and practice. The few African American workers who joined STO during this period left in the splits. By the mid-1970s, STO was reduced to six members.

Anti-Imperialist Work

In 1976 STO decided that the economic and political climate was at a “lull,” suggesting that workplace organizing would not be possible for some time. The group therefore should turn its attention to theory, education, and work in the anti-imperialist movements. (This is very similar to the notion of the “downturn” developed by Tony Cliff of the Socialist Workers Party of Great Britain in 1978 and then the International Socialist Organization of the United States shortly afterwards.) So in 1977 Ken Lawrence developed the STO’s mandatory “Dialectics Course” with reading from Hegel, Marx, Lenin, Luxemburg, Gramsci, Luckacs, C.L.R. James and Mark Twain (yes, that’s the same Mark Twain you’re thinking of). STO members would take a week off work and political activities to go out into the country for these sessions in which all members participated, first as students and then as instructors. The “Dialectics Course” helped to give the STO a reputation as one of the most intellectual and theoretical groups on the left.

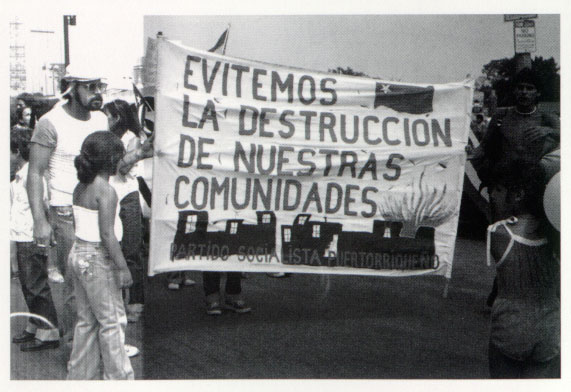

Puerto Rican Socialist Party at a demonstration.

Most of the group’s work at this time was in support for anti-imperialist struggles, particularly the struggle of Puerto Rico for independence. STO worked at first with the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP), a Marxist-Leninist party in Puerto Rico and the United States, closely aligned with Cuba. STO eventually, however, became part of the National Liberation Movement (MLN), a collection of left groups that supported the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN), a Puerto Rican group that set off 120 bombs in Chicago and New York between 1974 and 1983. STO members believed that they had to support the Puerto Ricans struggle against imperialism, including the armed struggle.

While STO sometimes differed with the FALN and other Puerto Rican groups, it would not make its political difference public because of the repression that the armed movement and other Puerto Rican organizations were facing. Consequently, STO’s own political positions became completely lost in its unconditional and apparently uncritical support of the MLN and FALN. Also, like some other left groups, STO took a position of support for the revolution in Iran, including initially backing the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini who ultimately brought the right-wing Islamic dictatorship. Similarly, STO found itself becoming an unconditional and uncritical supporter of Central American revolutionary movements during the period of its participation in the solidarity groups such as the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES). Throughout the years of this work, Staudenmaier explains, STO’s member worked frantically, rushing from one crisis to another, from one organization to another, until in the frenetic race from one emergency to another some in the group felt that they lost sight of their own identity and objectives.

Tendency Building and Direct Action

After five years of work in the anti-imperialist movements, STO changed its direction once again, this time to tendency building and an emphasis on direct action. STO had had a wealth of organizing experience, and despite being unable to point to many significant victories, its core ideas-—independent workers’ organizations and white skin privilege-—had become attractive to a number of organizations in cities in the Midwest and in some other areas of the country, most notably Denver, Colorado, and Portland, Oregon, though there was also an attempt at organizing in Mississippi. Led by STO, these local collectives now put their energies into the anti-war movement that had developed against Ronald Reagan’s wars in Central America and into the new anti-nuclear movement led by the Clamshell Alliance. STO was attracted to these movements because of their commitment to direct action, though appalled by their pacifism and opposition to violence, and frustrated by the middle class, white composition of the movements.

Student contingent at a 1987 rally led by CISPES against South African apartheid and US imperialism in Central America.

The attempt to build a national tendency eventually failed for several reasons. Since its founding in 1969 STO had been plagued by what Staudenmaier calls “informal hierarchies,” that is, a small group of the original founders-—Hamerquist, Ignatin, Travis, Lawrence, and a couple of others—-dominated the group whether or not they held formal office. They tended to develop the positions, write the documents, maintain contacts with local and national organizations, and determine the course of the group. STO failed throughout its history to establish democratic structures and processes and that both undermined its own functioning and proved an obstacle to establishing a national tendency. Then too, STO’s core theoretical concepts—-independent workers’ organizations and white skin privilege—-seemed to be unrelated to the group’s work in the anti-war and anti-nuclear movements in the 1980s, work which had little to do with the workplace or with winning white workers from their racism. Finally, demography was a real factor: many of the group’s members were aging, a few were parents with responsibilities for their children, and others, having left the industrial workplace, were moving on to other careers. (Ignatin, for example, born in 1940, turned 45 in 1985, and left the group a year before it died.) While STO had been interested in building an international tendency in the 1980s together with the autonomia groups in Italy and Germany, the debilitation of its own base in the United States made this impossible.

After STO withered away in 1986, several of its leaders went on to have interesting jobs and professions in other areas. Carole Travis, breaking with STO’s historic opposition to taking union office, became the president of United Auto Workers Local 719 at the GM Electromotive plant, serving three terms (nine years), and later went on to work for the Service Employees International Union as Director of the Illinois State Council for thirteen years. Most recently she participated in the Occupy movement in both Zuccotti Park and Oakland. Michael Goldfield became a professor of labor history at Wayne State University in Detroit focusing his research on workers’ movements and labor, and in particular on the failure of the labor unions to organize the South. Noel Ignatin became a professor at the Massachusetts College of Art, best known for his book How the Irish Became White and for his journal Race Traitor. The Sojourner Truth Organization’s survivors and successors have put its digital archives on the net, with as complete a collection as possible of its journals, newspaper, and pamphlets. Many of the former STO members retain their revolutionary socialist worldview and continue to contribute to movements as they have in some cases for fifty years.

The Lessons of the Experience

Sojourner Truth Organization represented only one of dozens of groups and involved only hundreds of the thousands of leftists who, in the period between the late 1960s and 1980s, were involved in attempts to build revolutionary organizations. American economic and political power, police repression, and the difficulties of developing a political theory and practice appropriate to the United States led all of those efforts to fail. In 1979-1981, most of the Maoist groups collapsed; the Socialist Workers Party, the largest Trotskyist group, after a belated and brief attempt at entering industry and the unions, evolved into a Castroite sect; the International Socialists split three ways between 1978 and 1979, and the New American Movement majority gave up its revolutionary vocation and merged with the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC) to form the Democratic Socialist of America (DSA). The STO suffered the common fate that befell what we can call the Generation of 1968.

After finishing Staudenmaier’s book, three points stand out in my mind. First, STO never succeeded in developing the democratic structures and processes necessary for an effective political organization. Second, STO’s two core theories-—white skin privilege and independent workers’ organizations-—never proved a guide to action. They did not accurately describe the nature of workers’ movements in the labor unions with their particular relationship to capital, nor did they adequately capture the nature of American racism in such a way as to guide the work of activists. Third, STO’s healthy concern about the autonomy of mass movements, workers’ organizations, and the struggles of African Americans and Latinos never emerged as a clear theory of any sort. While it always considered itself Leninist, STO never succeeded in describing the relationship between a revolutionary organization and the way it should relate to the movements in which it operates.

What lay behind the STO’s white skin privilege and union abstention theories? I suspect that STO’s theories were rooted in their attempts to grapple with the strengths and weaknesses of the Communist Party out of which either they or their parents had come. The white skin privilege theory expressed their profound frustration with the widespread racism of white workers—which had become so palpable South and North during the Civil Rights movement and the War in Vietnam—-and which proved so obdurate. The Communists—-despite the remarkable work they had done (not without its serious problems created by the vicissitudes of the Stalinist era, but better than everyone else’s), despite their often brilliant and courageous African American cadres, and despite their remarkable and also courageous white fighters against racism—-had not been able to turn the corner on the issue in a big way on a national scale (organizing the South being the big unfinished job as Goldfield has pointed out), though they did a remarkable job in various places during the CIO period. The race problem in America is just so terrible and so intractable. And then, of course, the Communist Party had by the late 1930s become tied to a strategy of trying to ally with or to penetrate the union bureaucracy, a policy which had further distorted its own Stalinist politics. STO leaders like Hamerquist, Ignatin, and Travis attempted to think their way out of these problems by developing critical theories of white racism and the nature of the labor bureaucracy, which is to their credit. But in the end, those two theories, this self-definition, failed to serve as a guide to action and also became so important to the group’s sense of its unique identity, that theory formed a barrier to practice, that is, to mass work, recruitment, and ultimately to the group’s survival.

Notes

[1] Others include: Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals turn to Lenin, Mao and Che (New York: Verso, 2002); A. Belden Field, Trotskyism and Maoism: Theory and Practice in France and the United States (New York: Praeger, 1988); Fred Ho et al., Legacy to Liberation: Politics and Culture of Revolutionary Asian Pacific America (AK Press, 2000); Milton Fisk, Socialism from Below in the United States: The Origins of the International Socialist Organization. Fisk’s book is really a history of the International Socialists (IS) up to the founding of the ISO. There are also many memoirs of revolutionary activists of the period now available.

[2] Dan La Botz, “The Tumultuous Teamsters of the 1970s,” in Aaron Brenner et al., eds., Rank and File Rebellion: Labor Militancy and Revolt from Below during the Long 1970s (New York: Verso, 2010). See also Dan La Botz, Rank and File Rebellion: Teamsters for a Democratic Union (New York: Verso, 1990).

This article originally appeared in New Politics.

Dan La Botz is a Cincinnati-based teacher, writer, activist, and member of Solidarity.

Comments

6 responses to “Lessons of the American Revolutionary Left of the 1970s: A Review of “Truth and Revolution””

Thanks to Jeffrey B. Perry for taking the time to respond as such length to my review. I appreciate him clarifying the original authorship of the “white skin privilege” concept, which, I agree (as I noted in my article) was first used by Ted Allen.

Perry, basing himself on Allen’s own argument, make the important point that racism was damaging to white workers and to the white working class. At the same time, it is obvious that “white skin privilege” provided immediate, short term, and ultimately consciousness distorting and disfiguring benefits to whites in the area of labor (employment, wages, promotion), in the area of society (less police harassment, arrests, convictions, beating, lynchings), and in politics (right to testify as a witness, right to sit in a jury, right to vote, stand for office). Obviously we would not be discussing “privileges” if there had been no benefits.

The real issue posed to the left was how to overcome racial prejudice that often among whites became racial hatred, a process which required not simply the slogan “black and white, united ad fight,” but support for African American demands for economic, social and political equality. The achievement of equality necessitated a recognition of the right of African Americans to self-organization both within society, labor unions, and left parties, as well as a self-conscious policy among African American allies of supporting affirmative action in all areas. The issues are parallel for Latinos in the United States, especially in the Southwest. Similar approaches prove to be important in overcoming male privileges over women and straight privileges over LGBT folks. While definitely not the same, the problems of oppressed groups prove to be analogous, and the touchstone of the political problems can be found in the notion of self-emancipation, even if it proves that self-emancipation of the working class, African Americans, Latinos, immigrants from everywhere, women, LGBT folk and all of us also means collaboration and the building of working class movement with a humanistic and emancipatory consciousness.

The symposium on Insurgent Notes is great. I urge those interested in STO and the left of the time to look at it.

I would like to thank Dan La Botz for commenting on my response to his review article “Lessons of the American Revolutionary Left of the 1970s: A Review of “Truth and Revolution.’”

In my first response I tried to do three things:

First I tried to make clear that, based on the historical record, Theodore W. Allen pioneered the “white-skin privilege” analysis in 1965 and he was the originator and principal developer of the theory.

Second, I tried to make clear that Allen did not consider “white-skin privileges” to be “benefits” for working people. Allen argues that “white-skin privileges” were created and maintained by the ruling-class to serve its interests for purposes of social control. He emphasized that “white-skin privileges,” conferred on European-American workers by the ruling class, are ruinous to the class interests of European-American workers and all workers and that “the day-to-day real interests of the white workers is not their white-skin privileges, but in the development of an ever expanding union of class conscious workers.”

Third, I tried to call attention to the importance of Allen’s writings, particularly the new Verso Books publication of his two-volume, magnum opus The Invention of the White Race, which is due out in November.

As I understand La Botz’ response to my posting, he accepts my first and second points on Allen’s pioneering role and that Allen did not consider “white-skin privileges” as a benefit.

Regarding my third point — I do not read La Botz’ response as one that encourages the reading of Allen. I feel that is unfortunate because, as I stated, Allen was a major anti-white supremacist working-class intellectual/activist whose writings have much to offer us today.

I am not alone in this sentiment. I encourage people to read the comments on Allen’s work by such scholars and labor, left, and anti-white supremacist activists as Bill Fletcher, Jr., Audrey Smedley, Tim Wise, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Gene Bruskin, Tami Gold, Muriel Tillinghast, Joe Berry, George Schmidt, Noel Inatiev, Carl Davidson, Mark Solomon, Gerald Horne, Wilson Moses, David Roediger Joe Wilson, Charles Lumpkins, Michel Zweig, Margery Freeman, Michael Goldfield, Spencer Sunshine, Ed Peeples, Russell Dale, Gwen-Midlo Hall, Sam Anderson, Gregory Meyerson, Younes Abouyoub, Peter Bohmer, Dennis O’Neill, Ted Pearson, Juliet Ucelli, Stella Winston, Sean J. Connolly, Vivien Sandlund, Dave Marsh, Russell R. Menard, Jonathan Scott, John D. Brewer, Richard Williams, William L. Vanderurg, Rodney Barker, and Matthew Frye Jacobson.

I also encourage people to read easily accessible Allen articles including:

“Class Struggle and the Origin of Racial Slavery: The Invention of the White Race”

“Summary of the Argument of “The Invention of the White Race”

“In Defense of Affirmative Action in Employment Policy”

“‘Race’ and ‘Ethnicity’: History and the 2000 Census”

“On Roediger’s ‘Wages of Whiteness’”

In addition, my article “The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy” offers a section (beginning on p. 99) on Allen’s last major unpublished work, “Toward a Revolution in Labor History.”

“The race-privilege policy is deliberate bourgeois class policy”

It Serves Ruling-Class Interests

In reading La Botz’ original review and response to my posting it seems that the position he initially inaccurately attributed to Theodore W. Allen – the idea that “white skin privileges” are a “benefit” to “white” workers – was in fact La Botz’ position, not Allen’s. If I read La Botz correctly, he says “white skin privilege” was a set of “benefits” that somehow “accrued to those deemed to be white” and, to La Botz, it is “obvious” that “‘white skin privilege’ provided immediate, short term . . . benefits to whites.”

Here is where I think that Allen’s anti-white supremacist, class-conscious historical analysis is particularly instructive.

Allen is talking about European-American workers, not about the “white” ruling class and not about the multi-class formation “whites” that La Botz says accrue “benefits.” Allen historically details how ruling-class “whites” benefit from the system of “white-skin privileges” – it is in their class interests. He is emphatic, however, that for European-American workers, “white-skin privileges” are not in their interest and they should be challenged.

Allen’s details the origin of the system of “white race privileges” as he argues:

1. The “white race” was invented as a ruling class social control formation and a system of “racial slavery,” a form of racial oppression, was implemented in response to labor solidarity as manifested in the latter (civil war) stages of Bacon’s Rebellion (1676-77).

2. A system of racial privileges was deliberately instituted as a conscious ruling-class policy in order to define and establish the “white race” as a social control formation

3. The consequence was not only ruinous to the interests of the African-American workers, it was also disastrous for “white” workers.

He also describes how “The normal course of capitalist events brings on a deterioration of the conditions of the laboring classes” and deep crises such as those of the 1870s, 1890s, and 1930s. In each of these “three periods of national crisis [the Civil War and Reconstruction, the Populist Revolt of 1890s, and the Great Depression of the 1930s] characterized by general confrontations between capital and urban and rural laboring classes” Allen details how “The key to the defeat of the forces of democracy, labor and socialism was in each case achieved by ruling-class appeals to white supremacism, basically by fostering white-skin privileges of laboring-class European-Americans.”

“The “Developing Conjuncture . . .” (pp. 34, 87-89) article cited above describes how Allen developed the “white race” privilege concept and how he emphasized that these privileges were a “poison bait” and they “do not permit” the masses of European-American workers nor their children “to escape” from that class. He explained, “It is not that the ordinary white worker gets more than he must have to support himself,” but “the black worker gets less than the white worker.” By, thus “inducing, reinforcing and perpetuating racist attitudes on the part of the white workers, the present-day power masters get the political support of the rank-and-file of the white workers in critical situations, and without having to share with them their super profits in the slightest measure.” As one example, to support his position Allen used statistics showing that in the South where race privilege “has always been most emphasized . . . the white workers have fared worse than the white workers in the rest of the country.”

Probing more deeply, Allen offered an additional important insight into why these race privileges are conferred by the ruling class. He pointed out that “the ideology of white racism” is “not appropriate to the white workers” because it is “contrary to their class interests.” Because of this “the bourgeoisie could not long have maintained this ideological influence over the white proletarians by mere racist ideology.” Under these circumstances white supremacist thought is “given a material basis in the form of the deliberately contrived system of race privileges for white workers.”

Allen added, “the white supremacist system that had originally been designed in around 1700 by the plantation bourgeoisie to protect the base, the chattel bond labor relation of production” also served “as a part of the ‘legal and political’ superstructure of the United States government that, until the Civil War, was dominated by the slaveholders with the complicity of the majority of the European-American workers.” Then, after emancipation, “the industrial and financial bourgeoisie found that it could be serviceable to their program of social control, anachronistic as it was, and incorporated it into their own ‘legal and political’ superstructure.”

Allen felt that two essential points must be kept in mind. First, “the race-privilege policy is deliberate bourgeois class policy.” Second, “the race-privilege policy is, contrary to surface appearance, contrary to the interests, short range as well as long range interests of not only the Black workers, but of the white workers as well.” He repeatedly emphasized that “the day-to-day real interests” of the European American worker “is not the white-skin privileges, but in the development of an ever-expanding union of class conscious workers.”

Allen made clear what he understood as the “interests of the working class” and referred to Marx and Engels in “The Communist Manifesto”: “1. In the national struggles of the proletarians of the different countries they point out and bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality. 2. In the various stages of development which the struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie has to pass through, they always and everywhere represent the interests of the movement as a whole.” He elsewhere pointed out, “The Wobblies caught the essence of it in their slogan: ‘An injury to one is an injury to all.’”

Throughout his work Allen emphasizes, “the initiator and the ultimate guarantor of the white skin-privileges of the white worker is not the white worker, but the white worker’s masters” and the masters do this because it is “an indispensable necessity for their continued class rule.” He describes how “an all-pervasive system of racial privileges was conferred on laboring-class European-Americans, rural and urban, exploited and insecure though they themselves were” and how “its threads, woven into the fabric of every aspect of daily life, of family, church, and state, have constituted the main historical guarantee of the rule of the ‘Titans,’ damping down anti-capitalist pressures, by making ‘race, and not class, the distinction in social life.’” That, “more than any other factor,” he argues, “has shaped the contours of American history – from the Constitutional Convention of 1787 to the Civil War, to the overthrow of Reconstruction, to the Populist Revolt of the 1890s, to the Great Depression, to the civil rights struggle and ‘white backlash’ of our own day.”

Based on his research Allen wrote, “history has shown that the white-skin privilege does not serve the real interests of the white workers, it also shows that the concomitant racist ideology has blinded them to that fact.” He emphasized, “‘Solidarity forever!’ means ‘Privileges never!’”

“Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?”

From the perspective of wanting to encourage reading of the writings of Theodore W. Allen, it is unfortunate that in his review La Botz, in addition to incorrectly characterizing a main aspect of Allen’s “white skin privilege” theory, also provides a link to a version of “White Blindspot” that is not the most complete version — it is a link to a version that doesn’t include Allen’s very important article “Can White Workers Radicals Be Radicalized?” [Note — “Workers” was crossed-out by Allen, but kept in the title. In the future this article will be cited using Workers/Radicals to indicate that the word “Workers” is crossed out and the word “Radicals” remains.]

The most complete version of “White Blindspot” had three component parts; the one that La Botz linked to only had two. As I explain in “The Developing Conjuncture . . .” — “the most complete version” was published as Noel Ignatin (Ignatiev) and Ted (Theodore W.) Allen, “‘White Blindspot’ & ‘Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?’” (Detroit: The Radical Education Project and New York: NYC Revolutionary Youth Movement, 1969). That stapled, mimeo publication had three components, an article by Ignatin and Allen entitled “White Blindspot,” “A Letter of Support” that was written by Allen, and Allen’s extremely important article “Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?” (The “White Blindspot” linked to by La Botz only had the first two pieces.)

The activist Dennis O’Neill, in “Some Thoughts on the Contributions of Ted Allen,” explains that Allen and Ignatiev wrote “‘White Blindspot’ (including another piece entitled ‘Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?’), which became one of dozens of pamphlets published by the SDS-affiliated Radical Education Project. Within six months of its publication, this cheaply mimeographed piece by two little-known authors set the terms for nearly all discussion of racism and what to do about it within the most influential radical group on US campuses. The concept quickly spread throughout the broader Left and there too set the terms in a discussion that had been raging since 1965.”

Thus, in terms of encouraging readers to read Allen’s important writings, it is unfortunate that when La Botz offered his link to “White Blindspot” it only included the first two pieces “White Blindspot” and “A Letter of Support” and it did not include Allen’s “Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?”

The more complete version of “White Blindspot”, with the three components and including Allen’s “Can White Workers/ Radicals Be Radicalized?” is available online and is also available as a link on my webpage in the section “Theodore W. Allen (with audio and video links)”. I very much encourage people to read it.

“Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?” takes up a number of issues that I think should be of special interest to readers today.

It first addresses the issue of “general historians and labor and socialist specialists” who “have sought to explain the ‘traditional’ generally low level of class consciousness of the United States working class as compared with that of the workers of many other industrial countries.” Writing in the late 1960s, Allen described the prevailing consensus among left and labor historians as a consensus that attributed the low level of class consciousness among American workers to such factors as the early development of civil liberties, the heterogeneity of the work force, the safety valve of homesteading opportunities in the west, the ease of social mobility, the relative shortage of labor, and the early development of “pure and simple trade unionism.”

Allen argued that the “classical consensus on the subject” was the product of the efforts of such writers as Frederick Engels, “co-founder with Karl Marx of the very theory of proletarian revolution”; Frederick A. Sorge, “main correspondent of Marx and Engels in the United States” and a socialist and labor activist for almost sixty years; Frederick Jackson Turner, giant of U.S. history; Richard T. Ely, Christian Socialist and author of “the first attempt at a labor history in the United States”; Morris Hillquit, founder and leading figure of the Socialist Party for almost two decades; John R. Commons, who, with his associates authored the first comprehensive history of the U.S. labor movement; Selig Perlman, a Commons associate who later authored A Theory of the Labor Movement; Mary Beard and Charles A. Beard, labor and general historians; and William Z. Foster, major figure in the history of U.S. communism with “his analyses of ‘American exceptionalism.’”

Allen challenged this “old consensus” as being “seriously flawed . . . by erroneous assumptions, one-sidedness, exaggeration, and above all, by white-blindness.” He also countered with his own theory that white supremacism, reinforced among European-Americans by “white-skin privilege,” was the main retardant of working-class consciousness in the U.S. and that efforts at radical social change should direct principal efforts at challenging the system of white supremacy and “white-skin privilege.”

Probing further, Allen also discussed reasons that the six-point rationale had lost much of its force and in so doing he provided important historical analysis. He noted that the free land safety valve theory had been “thoroughly discredited” for many reasons including that the bulk of the best lands were taken by railroads, mining companies, land companies, and speculators and that the costs of homesteading were prohibitive for eastern wage earners. He similarly pointed out that heterogeneity “may well . . . have brought . . . more strength than weakness to the United States labor and radical movement”; that the “rise of mass, ‘non aristocratic,’ industrial unions has not broken the basic pattern of opposition to a workers party, on the part of the leaders”; and that the “‘language problem’ in labor agitating and organizing never really posed any insurmountable obstacle.”

He then focused on what he described as “two basic and irrefutable themes.” First, whatever the state of class-consciousness may have been most of the time, “there have been occasional periods of widespread and violent eruption of radical thought and action on the part of the workers and poor farmers, white and black.” He cited Black labor’s valiant Reconstruction struggle; the Exodus of 1879; the “year of violence” in 1877 marked by “fiery revolts at every major terminal point across the country”; the period from “bloody Haymarket” in 1886 to the Pullman strike of 1894 during which “the U.S. army was called upon no less than 328 times to suppress labor’s struggles”; the Populists of the same period when Black and white poor farmers “joined hands for an instant in the South” and when Middle Western farmers decided to “raise less corn and more hell!”; and the labor struggles of the 1930’s marked by sit down strikes and the establishment of industrial unionism.

Allen emphasized that in such times “any proposal to discuss the relative backwardness of the United States workers and poor farmers would have had a ring of unreality.” He reasoned, “if, in such crises, the cause of labor was consistently defeated by force and cooptation; if no permanent advance of class consciousness in the form of a third, anti-capitalist, party was achieved . . . there must have been reasons more relevant than ‘free land’ that you couldn’t get; ‘free votes’ that you couldn’t cast, or couldn’t get counted; or ‘high wages’ for jobs you couldn’t find or

. . . the rest of the standard rationale.”

His second, “irrefutable” theme was that each of the facts of life in the classical consensus had to be “decisively altered when examined in the light of the centrality of the question of white supremacy and of the white-skin privileges of the white workers.” He again reasoned, “‘Free land,’ ‘constitutional liberties,’ ‘immigration,’ ‘high wages,’ ‘social mobility,’ ‘aristocracy of labor’” are “all, white-skin privileges” and “whatever their effect upon the thinking of white workers may be said to be, the same cannot be claimed in the case of the Negro.”

In another very compelling section of “Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?” (with great relevance today), Allen offered important historical analyses of three previous crises [the Civil War and Reconstruction, the Populist Revolt of 1890s, and the Great Depression of the 1930s] characterized by general confrontations between capital and urban and rural laboring classes. He explained how, in each case, the ruling class moved to maintain power by turns to white supremacy and by reinforcing “white race” privileges and, as he later summed up, “The key to the defeat of the forces of democracy, labor and socialism was in each case achieved by ruling-class appeals to white supremacism, basically by fostering white-skin privileges of laboring-class European-Americans.”

In yet another section of “Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?” (and in another section of “A Letter of Support”) Allen offers additional insights that should be of great interest to contemporary readers. Allen was a very serious and principled proletarian scholar and he tried to honestly identify and address objections people might have to what he was saying. As he would later do in his major work, “The Invention of the White Race,” Allen put forth arguments that might be raised by those who challenged what he said, and then sought to address those positions in an informed and principled way.

In “A Letter of Support” he specifically countered the arguments that: (1) he “exaggerate[d] the importance of the Negro question”; (2) that “the fight against white supremacy . . . cannot be regarded as THE key; there are others, equally important, such as the struggle against the Viet Nam war and imperialist war in general, or solidarity with the nationally oppressed peoples of the world struggling against the yoke of imperialism”; (3) “that the struggle against white supremacy and the corrupting effects of the white-skin privilege cannot be the key for the simple reason that it is not possible to ‘sell’ the idea to the white workers, who have those privileges and who are saturated with the white supremacist ideology of the Bourgeoisie” (or, as some argue, “That it is not really in the white workers’ interests” to oppose white supremacy); and (4) that what he proposed amounted “merely [to] whites reacting subjectively out of feelings of guilt.”

In “Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?” Allen similarly sought to “cut the ground out from all the artful-dodging” (the artful dodge concept is derived from the Charles Dickens character Jack Dawkins, who was known as the Artful Dodger, in “Oliver Twist”) of “white” “radicals” on the issue of the centrality of the fight against white supremacy. (Hence, the crossing out of the word “Workers” and insertion of the word “Radicals” in the title “Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?”)

The five artful dodges that Allen addressed and countered were:

1) “‘level up; don’t level down! . . . don’t ‘take anything away from the whites’”;

2) “the new working class – the technical specialists and educators – will be able to deal with the white-skin privilege . . . because they are almost completely insulated from the effects of Negro competition, they are not affected by the white supremacy that the lower orders of whites have taken on”;

3) “the immediate interests of the white workers are in conflict with those of the Negro, . . . But their long-range interests in ‘the revolution’ are in common. Therefore, we need a strategy of ‘parallel struggles’ with each group fighting for ‘its own interest’ against the Establishment. Eventually our efforts will join when the long-range tasks are at hand. In the meantime, however, racism cannot be the main issue among the white workers; at the same time it must be the main issue among the black workers.”;

4) “Eventually, when the depression and/or austerity times roll around, the corporations will move to cut their losses by reducing the privileges that they have extended to the white workers. When that time comes, the white workers will sing ‘Solidarity, forever!’ again and join the black workers in the struggle against capital”;

5) “Don’t waste time on the United States white workers . . . The privileges of these workers are paid for by the super-profits wrung out of the super-exploited black, yellow and brown labor . . . The victorious national liberation struggles of these peoples will, sooner, or later, chop off these sources of white-skin privilege funds. Then, not before, the white workers will ‘get the message.’ Meantime, the role of white radicals is simply to ‘support’ the colonial liberation struggles.”

Allen’s responses to the four arguments against and to the five artful dodges still have great relevance today. His responses can be found online in “‘White Blindspot’ and ‘Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?’ ‘. In another effort to stimulate the reading of works by Allen, I encourage readers to go directly to that site to read them in their entirety.

In sum, I would again strongly encourage people to read writings of the anti-white supremacist proletarian intellectual/activist Theodore W. Allen, to read (in particular) the newly expanded Verso Books edition of “The Invention of the White Race”, and to ponder Allen’s use of the word “Solidarity” taken from “Can White Workers/Radicals Be Radicalized?” — “‘Solidarity Forever!’ means ‘Privileges Never!’”

The anti-white supremacist, working class intellectual/activist Theodore W. (Ted) Allen (1919-2005) was one of the most important writers on race and class in twentieth-century America. His seminal, two-volume magnum opus, The Invention of the White Race, which is being published in a new expanded edition by Verso Books in November 2012, is increasingly recognized as a classic and his writings have much to offer us today.

For a host of reasons, however, Allen’s writings have often been inaccurately described, improperly cited, and ignored rather than having been read, engaged with, and given the serious attention they merit.

It is with the aim of encouraging engagement with Allen’s work in mind, and in a fraternal spirit, that I offer the following comments in response to Dan La Botz’ statements about Allen.

1. Regarding La Botz’ statement that “white skin privilege” was “a theory first suggested by Noel Ignatin and Ted Allen” –

As documented and discussed in my 2010 Cultural Logic article “The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights From Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Struggle Against White Supremacy (esp. pp. 8-9, 31-34) the record is quite clear that Theodore W. Allen pioneered the “white skin privilege” analysis in 1965 and that he was the originator and principal developer of the theory.

Noel Ignatin (Ignatiev), explains: “My first act in 1966 on finding myself outside the group [POC] was to get back in touch with Molly [Theodore W. ‘Ted’ Allen]. It was then he introduced me to his thinking on white-skin privilege, which he had developed after he left the POC [in 1962] . . . not to be too grandiose about it, if Ted was Darwin, I was his Huxley.” (Noel Ignatiev to author, June 17, 2005, possession of author.)

Ignatiev adds that in the fall of 1966 he became convinced of “the correctness” of the “position that the white-skin privilege has been the Achilles’ heel of the labor movement in the US, and that the fight against white supremacy (beginning among white workers, with the repudiation of the white-skin privilege) is the key to strategy for revolution in this country.” (Noel Ignatin (Ignatiev) “Author’s Note,” October 5, 1969, in Noel Ignatin and Ted (Theodore W.) Allen, “White Blindspot” & “Can White Workers [crossed out] Radicals Be Radicalized?” (Detroit: The Radical Education Project and New York: NYC Revolutionary Youth Movement, 1969.)

2. Regarding La Botz’ statement that Allen argued that “white skin privilege” was a set of “benefits” that “accrued to those determined to be white” — this is simply not what Allen argued.

Allen repeatedly argued that for European-American workers the “white skin privileges” were not “benefits” – they were “poison,” “ruinous,” a baited hook – they were against the class interests of working people. (See “The Developing Conjuncture . . .” pp. 34, 78-80.)

He emphasized that the ruling class deliberately instituted and maintains a system of “white skin privileges” (in their class interests) for purposes of social control.

In the above cited “Can White Workers [crossed out] Radicals Be Radicalized?” article (pp. 15, 18) Allen writes: “history has shown that the white-skin privilege does not serve the interests of the white workers, it also shows that the concomitant racist ideology has blinded them to that fact.” He further explains, “The day-to-day real interests of the white workers is not the white skin privileges, but in the development of an ever expanding union of class conscious workers, white and black.”

In his 1975 pamphlet Class Struggle and the Origin of Racial Slavery: The Invention of the White Race Allen explains that the “three essentials [that] have informed my own approach in a book I have for several years been engaged in writing . . . on the origin of racial slavery, white supremacy and the system of racial privileges of white labor in this country” are:

Clearly, Allen consistently argued that “white skin privileges” are not “benefits” – rather, they are ruinous to the class interests of European-American workers and all workers.

Finally, I think it important to call attention to the fact that Allen pointed out that slogans such as “‘Solidarity forever!’ means ‘Privileges never!’” have meaning for contemporary struggles as do such slogans as “Workers of the world unite,” “Abolish the wage system,” and “An injury to one is an injury to all!”

Thus, in addition to encouraging people to read Allen’s writings, I would also like to encourage readers of “Solidarity,” while looking at the masthead, to think about the slogan “‘Solidarity forever!’ means ‘Privileges never!’”

This is a wonderful review by Dan Labotz–I’m ordering the book right away. Let us hope that veterans of the I.S. and other revolutionary organization will provide us with studies as rich, candid, and well-documented as this one appears to be.

We have published a symposium on Staudenmaier’s book in the new issue of Insurgent Notes (http://insurgentnotes.com). It includes contributions from members of STO, younger activists influenced by the organization and a response by Mike.

John Garvey