Posted March 8, 2009

March 8 is celebrated around the world as International Women’s Day, but IWD is not very well known or celebrated in the country of its birth. Fortunately the feminist movement of the 1970s has at least partially uncovered and reintroduced it.

IWD arose out of the work of the Socialist Party’s Women’s Commission, which demanded in 1910 that the party set aside a special day to coordinate on a national level the campaign for women’s suffrage.

Dozens of socialist papers carried special articles about the need for women’s suffrage and leaflets were distributed in the various languages of the U.S. working class spoke then. Between 1896-1910 no state had been added to the suffrage column–but between 1910-1917 the party played an important role in winning women’s suffrage in five states: California, Kansas and Nevada in 1912 and New York and Oklahoma in 1917.

Following on the success of the initial action, the party proposed to the congress of the Second International that the action become an international event, as it has been for nearly a century.

In addition, American socialist feminists of that period were very active around the fight for “voluntary motherhood,” as the struggle for women’s right to make reproductive choices was then known. Socialist feminists also discussed what kind of housing arrangements would work best for the world they wanted to build–suggesting child care centers and communal kitchens ought to be built in apartment complexes.

Louise Kneeland summed up the perspective of a growing number of socialist feminists when she wrote, in 1914: “The socialist who is not a Feminist lacks breadth. The Feminist who is not a Socialist is lacking in strategy.”

Comments

2 responses to “The Origins of International Women’s Day”

The origins of International Women’s Day (IWD) arose from the labor movement at the same time of rapid industrialization. In conjunction with this trend, the beginning of the 20th century also marked a time of global economic expansion. These times of widespread change were the effects of not only the maturation of manufacturing but because of the labor movement’s protests over working conditions. On 8 March 1857, female garment workers, many of them immigrants, from clothing and textile factories protests in New York City for fair and living wages along with better working conditions. These same women established their first union 2 years later.

This day of recognition came from a need for better labor conditions. Women were entering the industrial labor sector and introduced to the corruption of a capitalist production process. The socialist, working-class, and struggle origins of International Women’s Day are generally concealed by maintsream media in favor of identity-based politics like feminism. The real history and meaning behind this commemorative day have been demonstrated by women worldwide with displays of solidarity and resistance against capitalism. The history of this day goes beyond the need to eradicate patriarchy, and is a history of the labor movement’s ability to revolutionize society.

Inspired by that march in 1857, women immigrant garment workers staged a three-month strike against Triangle Shirtwaist and other sweatshops in 1909-10 aka “Uprising of the 20,000.” Women, as young as 16 years, confronted police battalions in the harsh of winter. Only one year later, 146 immigrant workers, women and girls, perished in the horrific Triangle Shirtwaist fire. This is why IWD protests continue to demand workplace safety regulations and memorialize those who have lost their lives over the pursuit of capital.

Days of observation can be really important for several reasons. Understanding our history, as workers, opens our eyes to how change is done. The protests mentioned above are a perfect example of what happens when we learn from history. Those women followed suit and organized in the late 19th century against labor exploitation and actually gained rights within their garment factories. These women learned a lesson from history by deciding to rise up against unjust work. Their actions and winning rights as a result, became a symbol on IWD. It is the symbol of solidarity between working women across all borders, and the symbol of organized resistance against the unjust.

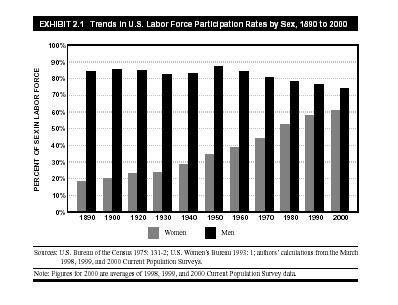

These actions spawned the birth of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in the 1960s, as well as other organizations representative of working-class women and women of color like 9to5: The National Organization of Working Women and the Coalition of Labor Union Women. It was these groups that the women’s movement of the 1960s and ’70s built itself upon. There is debate over whether the successes of these organizations were due to their direct organizing or their legal efforts. Major changes occurred in the status of working women between the ’60s and ’80s.

Legal restrictions on gender-based occupations were loosened, and pay discrimination eliminated. The gender wage gap narrowed, and occupational segregation rapidly followed in the 1970s. The wage gap continues to shrink, as working-class women were making 77 cents for every dollar a man was making in 2005, compared to 59 cents forty years earlier in 1964.

In the 1990s these improving trends began to stagnate, and in some circumstances digress. Inequalities in the workforce were growing between white women and black women, also distinguished as women with different levels of education. Economic changes can explain this emerging pattern, such as off-shoring of factory jobs and service industry expansion. The social movements of this time period are also much to blame for the segmentation of the working class.

Much of the upward mobility we see from women in the workplace is that of white, college-educated women. These gains should not be overlooked as trifling, but we have to look at the whole story to understand why this trend occurs. Her success is not a universal or a given; there are very specific conditions that allow for this sort of mobility. Struggling to balance a job and a family really limit the chances to be in control of your labor, because there are no support systems in our society to help deal with this.

In 2005 only 27% of all women over the age of 25 obtained a college degree. Only 19% of black women within this age group had a college degree, and the same went for just 12% of Hispanic women. There are significant discrepancies between race and ethnicity that give white women an advantage in society. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics just released an entire report with statistics on women in the labor force.

Workplaces don’t usually offer childcare and it’s hard to find a fair-wage job with schedule flexibility. If you don’t have children or a family to support, than your ability to develop in the capitalist mode of production is enhanced. This is not to mention that, at this point in time, job security is almost void which does much to prevent struggling women (and men) to climb the status ladder.

36% of female-headed families with children under the age of 18 are living in poverty. This is a percentage worked out from 2000 which is steadily rising meaning this situation is only worsening. There are very few women employed within higher-waged occupations because of serious barriers of educational attainment and sexual harassment. Even occupations that don’t require college educations show an oppressive wage gap between males and females. Janitors, who are primarily men, earned an average wage of $10.15/hr in 2005. Maids and housekeepers, who are primarily women, earned an average of $8.74/hr that same year. The same is seen in the field of nursing where men earned $16.96/hr on average and women earned $10.67. Click here for an update on these statistics.

These trends demonstrate how entering the paid labor force does not translate into a rise in class position. Class mobility is low in the United States and research suggests it is decreasing with time. Gaps are widening between different social-identities, especially those based on race and ethnicity. There are other factors and relationships significantly influencing changes in our social conditions, however. The ways in which we organize and act also explain the trends of labor.

The framework for which we exert our agency affects the outcomes of our struggles. After World War II the U.S. labor movement failed to organize collectively as a working-class. This can be seen in select actions. Instead of fighting for universal health care, the labor movement won employer-based health care. The interest of improving working conditions and employment opportunities for all workers was pushed aside for the sole interest of union workers. This was a snap in the rope of solidarity bonding all members of the working-class, non-union workers included. This divided workers, as well as weakened the fight for non-unionized workers’ rights to health care and job security.

Changes that were made by workers post-WWII were thus products of individual legislative victories, not the collective action of united workers. People were forced to search outside of the labor movement to find a medium for their agency. Workers were pushed out by their comrades, and forced into identity-based organizing. This is when the civil rights movement of the 1960s became so powerful in terms of granting employee rights. The approach of today’s women’s movement is based on this same methodology.

Individual solutions have been granted, and victories have been won within this schema. Identity-based social organizations have used their successes to emphasize individual strategies for working-class women. To decrease the wage gap they advocate for more programs that get women into college, rather than organizing within the workplace and fight for fair wages at the shop floors. Education isn’t equally available for all members of society, so the solution can’t be based in programs improving chances for women to enter college. Some of these women never made it through grade school because they couldn’t learn to read. If we want to decrease the wage gap, we’ve got to fight for our rights where we have the most control. This is in the workplace. We could use legislation to argue for better pay, but unionizing and acting collectively to approach payroll supervisors is much more direct and progressive. We’ve got to organize around the process of production we are a part of all day long. We’ve got to use our labor, our means of existence, as an agent of change. Using our social identities, like advocating feminism, lead us down a dead end road. Labor movements, on the contrary, do not end.

Women who have benefited from individually-focused solutions should use their power to get lawyers, lobbyists and voter to win on the collective’s behalf. Unionization has improved wages and job quality for working-class women in the United States. 9to5, now with members in all states, organized to help pass the Civil Rights Act of 1991, the Family and Medical Leave Act, state health and safety laws, as well as local living-wage ordinances. They’re worked directly with their locals, on individual shop floors, as well as reached out to the national community to fight for all workers’ rights. These successes are sustainable and empowering for all people, all workers.

The struggle is no where near complete. The largest occupations for women have lower than average union density rates. Jobs, like waitressing or cashiering, come with very little social power. The employees are viewed as easily replaceable.

This is to say that most women workers are not benefiting from individual, identity-based solutions or the collective efforts of unionization. Collective action is limited by our lack of class consciousness. Mark Brenner and Stephanie Luce write, “First, in the short term, they can only address job quality, and not class position. Even with greater union density in all female-dominated occupations, if we are still living in a class economy, working women would still be exploited by their employer and alienated from their labor. Second, collective approaches that are only aimed at improving wages and job quality are still limited in the impact they can have on the lives of working women, because they do not address the social reproduction of labor. Women need collective solutions to non-market activity as well as market activity.”

So, as we venerate the 101st IWD, let’s remember what Brenner and Luce continue to argue, “…most organizations today that are concerned with issues related to women and work are ultimately hemmed in by the framework of equalizing market access: recommending more job training for women so that they can fill higher-wage jobs; child-care subsidies so that more women can enter the labor market; and comparable worth policies that force employers to recognize and fairly compensate women’s human capital. In the end, these solutions can only improve the chances that women gain access to well-paid working-class jobs, or at best, leave the class all together. What this approach leaves hidden is an acknowledgment that class, at the core, is a system where workers and employers have inherently opposing interests. The primary challenge facing working-class women and their allies today is how to fight for better conditions for workers under capitalism, while recognizing — and struggling to overcome — the limits of capitalist as a system. The experience of women in the United States in the last forty years has made abundantly clear that there will always be competition for the living-wage jobs that exist under capitalism, and the ways in which those jobs are parceled out will be influenced by systems of patriarchy and racial oppression. Individual solutions based on market access won’t be enough: women also need class-based solutions. In fact, individual solutions have only exacerbated the problem for many women.”

In the spirit of IWD, rise up and grab arms, the patriarchy is calling for duty. Down with sexism and down with racism as social dividers. Unite as a working-class of laborers, and fight for permanent solutions to the exploitation, oppression, and alienation of our labor.

Hate the fact that eight hours a day

Is wasted on chasing the dream of someone that isn’t us

And we may not hate our jobs

But we hate jobs in general

That don’t have to do with fighting our own causes

We the American working population

Hate the nine-to-five day-in day-out

When we’d rather be supporting ourselves

By being paid to perfect the pastimes

That we have harbored based solely on the fact

That it makes us smile if it sounds dope!

– 9-5ers Anthem, Aesop Rock

Continuing on in the spirit of IWD, and for some of the most amazing material on women and class please read Women and the Politics of Class by Johanna Brenner.

Thought I would share this question-and-answer piece by a local collective:

What is International Women’s Day?

International Women’s Day is an annual day of recognition observed around the world on the Eighth of March. We celebrate the achievements and contributions of women in the past. We educate each other about the conditions, needs, rights, and demands of women in the present. We mobilize everyone, women and men, for the complete liberation of women and all people in the future. In the United States, IWD is now the anchor of Women’s History Month in March.

What is the goal of IWD?

The overarching goal of IWD is to promote friendship, understanding, and solidarity among women worldwide. In a divided and unequal world, we “hold up half the sky.” Coming from all countries, cultures, communities, and classes, women can find commonality in diversity. United, we are a tremendous force for peace and justice, locally and globally.

What are the origins of IWD?

The origins of International Women’s Day are found a century ago in the labor and women’s movements in the U.S. New York women socialists rallied for women’s suffrage in March 1908, and the American Socialist Party observed National Woman’s Day in February 1909. These actions were reinforced by a great strike movement among women workers in the garment and needle trades. Following the call of the German socialist leader Clara Zetkin, the first International Women’s Day was held in March 1911. Marches, rallies, and strikes in observance of IWD grew over the next several years, despite the outbreak of the First World War. In fact, peace activists founded the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in 1915. The culmination of these protests was the famous strike of Russian women workers in 1917, which sparked the Russian Revolution. In honor of these women, the Eighth of March became the date for IWD worldwide in 1918.

Was there a global women’s movement to take up IWD?

Women were on the move after the turn of the twentieth century. Formed in 1904, the International Woman Suffrage Alliance brought together suffragists who aspired to full citizenship in their own independent countries. This first wave of global feminism was by no means confined to the U.S. and Europe. In the colonial and dependent countries, the demands for national self-determination and women’s self-determination were often intertwined. Women played active and visible roles in the Iranian, Mexican, and Chinese revolutions and in protests against colonial rule and white supremacy in India and South Africa. Mexican women held two Yucatán Feminist Congresses in 1916, and Latin American women organized an International Feminine Congress in Argentina in 1919. After both Muslim and Christian women participated in the Egyptian revolt against British rule in 1919, Huda Shaarawi founded the Egyptian Feminist Union in 1923. Some 25,000 Chinese women celebrated IWD in Guangzhou in 1927. The Pan Pacific Women’s Conference in 1928, the All Asian Women’s Conference in 1931, and the Arab Women’s Conference in 1944 were all signs of the worldwide scope of women’s activism. For example, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, who founded the Abeokuta Women’s Union in 1946 when Nigeria was still under British rule, soon emerged as an international as well as national activist and leader. Increasingly, women won the right to vote in conjunction with decolonization or revolution.

Did the observance of IWD + women’s suffrage = the emancipation of women?

In 1922 International Women’s Day became a day of recognition for women in the Soviet Union. After the Second World War, it became a public holiday in China and other socialist countries. However, the onset of the Cold War discouraged the widespread observance of IWD in the U.S. Although the equality of women and men was a cornerstone of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, many women did not really enjoy free and full participation in government and society. For example, some or all women of color and indigenous women were denied the right to vote in the U.S., Australia, Canada, and South Africa. Even when women were enfranchised, as most were worldwide by 1980, formal and informal bars stood in the way of access to education, employment, property, and the professions; freedom of sexual orientation, gender expression, marriage, and divorce; legal availability of contraception and abortion; and security against sexual and domestic violence.

Who revived the observance of IWD?

Women were on the move once again in the 1960s. In the U.S., women in the civil rights and antiwar movements challenged men who tried to subordinate them. Many women – working women and housewives, women of color and white women, older as well as younger women – began to demand changes in the homes, workplaces, and communities they shared with men. Some younger feminists went on to found the movement known as Women’s Liberation by forming consciousness-raising groups, studying women’s history, protesting the Miss America pageant in 1968, and reviving the observance of IWD in many cities in 1969 and 1970. The Great Speckled Bird, Atlanta’s underground newspaper, publicized IWD in March 1969. Thus this year’s observance marks the fortieth anniversary of the revival of IWD in Atlanta.

What was internationalist about the revived observance of IWD in the U.S.?

In the U.S., the observance of IWD foregrounded the rich history of women’s abolitionist, suffrage, and labor activism. Equally important, it was internationalist in two senses, reflecting what many saw as the inner and outer dimensions of a U.S. empire. On the one hand, IWD highlighted the activism of African American, Asian American, Chicana, Puerto Rican, and Native American women – the women of communities and peoples suffering from racial and national oppression inside the U.S. On the other hand, IWD highlighted the struggles of women in Chile, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Palestine, the Philippines, South Africa, Vietnam, and other countries – the women of countries affected in one way or another by the actions of the U.S. government and corporations.

When did the United Nations recognize IWD?

The second wave of global feminism has surged from the 1970s through to the present. The United Nations recognized IWD in 1975, at the start of a series of conferences on global women’s issues held in Mexico City, Copenhagen, Nairobi, and Beijing. It adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 1979. CEDAW is a component of the international human rights framework. By the time the fiftieth anniversary of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights was celebrated in 1998, the principle that women’s rights are human rights was widely acknowledged.

What does it mean to observe IWD in 2009?

Observing IWD 2009 is not just an opportunity to look back to National Woman’s Day in 1909 or the revival of IWD in 1969. In recent years, younger women, women of color, immigrant and indigenous women, LGBTQ women, and Muslim women in the U.S. have continued to infuse feminism with new demands and enliven it with new energies. We have learned how forms of oppressions are interlocked and how we can take an intersectional approach to build alliances and unlock the system of oppression. To the extent that it reflects an inclusive vision of women, IWD is part of this grassroots, living, twenty-first century feminism.

Where do we go from here with IWD?

We are living in a moment of profound crisis and reform following a long period of backlash and reaction. Now more than ever we need to grasp the interconnected nature of the issues facing us, locally and globally. We need to find inspiration in the worldwide efforts of women in the past to better organize to scale to meet the challenges of our times in the global South and global North. One way forward concerns the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. In 1980, the U.S. government signed CEDAW, but ever since the senate has refused to ratify it. Much like the ill-fated Equal Rights Amendment, the failure to implement and enforce CEDAW reminds us that powerful forces in our society actually support hierarchies of gender, race, and class and oppose the inclusion and empowerment of all women. Perhaps when we observe IWD 2010 we will be talking about a movement in metro Atlanta to pass municipal and county human rights charters and CEDAW ordinances?