Posted June 16, 2008

The name Ashok Kumar rings a few bells: the field hockey star who helped win the 1974 World Cup? The famous Bollywood star who played the main character of India’s first soap opera? The jazz aficionado who, since 1997, has served in the British Parliament? Well – that last one is getting warmer, at least.

This afternoon I chatted on the phone with Ashok Kumar, the recent UW Madison graduate. Ashok and me have shared some memorable experiences – clubbing on Miami’s South Beach with his former frat brother, hanging out at Detroit’s Bronx Bar… I think we might have even crashed a hotel pool together last summer at the US Social Forum. Today, though, we talked about his experience as a socialist in elected office. For the past two years, Ashok served as a supervisor on the Dane County board, representing the progressive independent political party, Progressive Dane.

Know your Ashoks!

Isaac: How did you become involved in radical politics? What is your family background?

Ashok: My grandparents on my mother’s side were very active in the anti-colonial movements, the independence movement in India. My grandfather was arrested. On my father’s side, there were a lot of labor leaders and some members of parliament who belonged to the Communist Party of India-Marxist. My parents are very radical. So that’s the way me and my brother were raised in Chicago: we went to marches and other things that my father took us to at a young age. When I was thirteen, I briefly joined the Socialist Party. By the time I got to college at the University of Wisconsin, I felt that a lot of these sentiments could be crystallized into movement work. That’s the rough background.

When did you start college, and what were you involved with before getting into office?

I began college in 2003 and immediately began to be involved with tuition issues, access to higher education and affirmative action placement programs. I was in student government and in student of color organizations. So that was a two-year fight, and we failed. We organized on a lot of fronts: marches, rallies, hunger strikes, and an occupation of the military recruitment office. In the end, the Democratic governor of Wisconsin increased tuition by 67%. So I moved on to labor organizing with the Student Labor Action Coalition. Some students were doing anti-sweatshop campaigns, which I wasn’t particularly involved in – I focused more on working with local labor struggles. These experiences further radicalized me because of the people that I met.

The weird thing was that I was also in a fraternity at the time and people thought that it was strange that I related to the Greek world, to involvement in student government, and to the radical activist community in Madison. I ran for freshman class president my first year and in my fraternity helped initiate a “train the trainers” kind of activity where we instituted classes on anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-homophobia and challenging the hyper-masculinity of many fraternities. That program is now paid for by the school and all the frats take it.

Tell me about your campaign. What was your district like? How did you decide to run for office as an independent candidate?

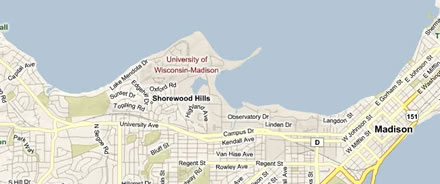

Dane County as a whole has over 60 cities, towns, and villages, half a million people and about a half-billion dollar budget controlled by the county board. The Fifth District is the most densely populated in the county. My district runs along Lake Mendota through downtown Madison and has five wards. One of the wards is Eagle Heights, which is mostly families, very international – about 70% immigrants. There are a lot of grad students and professors that live in another ward, Shorewood Hills. The district includes the entire university, Unity Hospital, the commercial district of State Street, and also has a lot of high-rise buildings. There’s student housing and transitional housing for people coming off substance abuse problems.

Downtown Madison, Dane County’s Fifth District

Progressive Dane is a local left-wing party that has existed for about fifteen years. It’s one of the last vestiges of a third-party movement in the early ‘90s, the New Party, along with the Progressive Party in Vermont and, to a lesser degree, the Working Families Party in New York. A number of the Progressive Dane people, and from the Green Party, said they would really like a strong candidate to run for a seat representing the Fifth District and asked if I would be interested.

At the same time, the chair of the local Democratic Party had heard that I might run as a Democrat and was afraid I might possibly run as candidate for a left party. So they decided to run some people against me, but also tried to get me to compete for the Dem endorsement in their primary. So they sat me down with this kid Awais Khalil – “Hey, he’s a brown guy! Let’s get them to talk!” – he’s actually the vice president of the College Democrats of America. He said, “Hey, you should really think about running with the Dems. If you run as a third party candidate, we’ll crush you.” Of course that motivated me even more to run!

So, I announced I was going to run and three days later the student newspaper, the Badger-Herald, ran a full page editorial called “Absolutely NOT.” People called me a “Trotskyite wannabe.” A “bomb-throwing Trotskyite wannabe,” actually. Then the right-wing paper, the Mendota Beacon, said that I was being propelled by extremist campus labor forces. So that was the beginning of a lot of attacks I faced from the right wing papers in Madison. About four other people also announced after that, as well, so this was the most contested race in the county at the time.

Could you talk about your political platform and your base of support in the election?

The primary issues that I addressed when I announced were criminal justice related. That was really the rationale for my run. I was working with a multiracial student coalition and the main thing I wanted to work on was this absolutely horrific statistic that we had. Dane County had, at the time, the worst Black-to-white incarceration rate in the country. Right now, it’s still the third worst in the country: 97 African Americans arrested on drug charges for every one white person. It was worse – I’m not sure what it was, but it was pretty bad! I wanted to create an elected civilian review board to look into this, and have a program where if a deputy arrested a high number of African Americans, they would go before the board. The white papers and radio stations really opposed this. I also did some stuff with immigration issues – and fighting the war on drugs, which resonated with the student population.

I also talked about Section 8 housing equality and ending housing discrimination. At the time, over 3,000 families – about 65% of them Black, and another 20% Latino – were on Section 8 housing assistance. But they were limited to only 20% of the housing stock. Those were in the lowest income, highest crime areas and landlords were taking advantage of the families because they had nowhere else to go. There had been the creation of ghettoized communities of color in a program that was supposedly meant not to do that. I said I would pass a law that would mandate all landlords must accept Section 8 vouchers. This was also controversial, with the Landlord Council funding my opponents.

Endorsements from groups like the Sierra Club, the National Organization for Women, and campus groups ended up building a sense of legitimacy with the broader public. I also had a lot of contacts among fraternities and sororities as well as in the co-op housing community in my district. All of this was helpful in the face of ongoing attacks from the press, including some messed-up stuff about my personal life that had a racist character. Some of these attacks actually backfired and won me some support because they were so ridiculous.

My base came from all over – the near east side, and endorsements from the Green Party, Progressive Dane, and the Socialist Party. A lot of support came from labor activists. We got the Central Labor Council endorsement even though AFSCME and some of the building trades were really opposed. At the vote, we just packed the room. Some campus unions – like AFSCME 171, the blue collar workers union, and the Teachers Assistant Association, had already endorsed me.

We ended up running the campaign on a shoestring budget. The average donation to the campaign was something like $8 and 80% of donations were from within the district. A lot of people came out to support us on the ground. There are about 15,000 people that live in the district and we knocked on every single door. Our literature just compared me with my opponents, rather than being attack ads. We had to do this because the other candidates which were better funded had all sorts of negative campaign literature that we had to respond to with clear positions.

In the four-way primary, I ended up picking up about 55% and then got 70% in the general election against the Republican candidate. [ed. note: in the recent 2008 election, there were fewer total votes in District 5 than voted for Kumar in 2006]

What was your main objective once in office? What were some of your larger goals, and what did you accomplish during your two years on the county board?

Everything I had done in the past focused on labor, housing, and criminal justice issues. But I realized that if there wasn’t much ground level activity going on, win or lose, the ultimate value of a policy is whether or not it organizes people. There’s a dual benefit to taking on some policy issue. When you have a victory, you win, but people also come to realize a sense of their own power. But even if I didn’t feel passionate about grassroots change, often you need that kind of organizing to win in the first place.

I had some basic platform issues but the policy I worked on was very influenced by what people were doing on the ground. For example, people had been fighting around the Section 8 issue for years, but had failed due to vetoes by the mayor and other setbacks. It had been fought over a decade and hadn’t been won, but there were still people passionate about the issue. I introduced the reform probably about a month after I got into office.

The day it came up, the room was packed: probably twice as many people on the left side, almost all Black and Brown, and on the right side it was male, pale, and stale. A bunch of old white people. The meeting lasted until 3am because there was so much testimony. We ended up passing it, and then succeeded in defeating an attempted repeal a few months later which had been introduced by the Madison Landlord Council. All of this happened because of the ground-level organizing, in every district, with the Affordable Housing Action Alliance pushing all of the county supervisors. The Democrats even came on board this time, although they had opposed it in the past.

Another example. There were also situations with issues that I didn’t personally feel very passionate about, but where there was grassroots organizing happening. There was an impeachment resolution that called for the impeachment of Bush, Cheney, and Gonzales (until he ended up resigning anyway.) This was coming from people who had supported my campaign – mainly older white people who did not relate to many local issues. So I said, if they’re organizing around it I would be happy to introduce it on the board. We became the second county to pass that resolution, with only three votes against, which was shocking because it hadn’t happened at the city level. I wasn’t really hyped about it, but people were organizing and, hey, it’s a good thing. It’s not a bad thing.

We have a vibrant and growing immigrant population in Madison, primarily Latino and Hmong people. They had been organizing with a number of strong, community based organizations such as the Immigrant Workers Union (mainly Latinos and Latinas) and Freedom, Inc (which was the Hmong organization.)

The target of their organizing was the sheriff. A few years back, Madison instituted a sanctuary policy that says we won’t ask for people’s immigration status on behalf of the federal government. But this new sheriff had started to arrest people and turn them in to ICE, even though this was a violation of county policy. Because the issue was criminal justice related, we were also able to develop a coalition with some Black organizations. There were a series of overflowing public hearings – Black, Latino, Hmong, lawyers, everybody. It was hot.

I also happened to be the treasurer of the public protection judiciary committee, which is the main overseer of the Sheriff’s Department and their budget. So we called a public hearing, brought out the media, and then two weeks later had a rally with 700 people. There wasn’t a policy or law I could work on that people could organize around, but given my position in the halls of (relative) power I could put together something like that that would allow people to come and not just yell at the sheriff, but add legitimacy to the issue and push public discussion to the left. Rather than operating from a defensive position, we went on the offensive.

Some other things weren’t as successful. We tried this program which would have given any resident of Dane County an ID, to protect people from anti-immigrant ID laws. There was a lot of press – this was the second initiative of its kind, after one in New Haven, Connecticut – it was on the cover of USA Today. We weren’t able to pass that, though.

One more area that crossed over between housing rights and immigrant rights was a series of forty-five or fifty amendments to strengthen the housing ordinance. We got full housing rights for undocumented people, full housing rights for ex-felons, for transgendered people – an across-the-board expansion of the law. Fines for discriminating against tenants would be raised to $50,000, and tripled and quadrupled for landlords who were repeat violators. We also sought to establish programs that gave a significant amount of the money to the tenants themselves. It was a great example of cross-community organizing that ended up getting vetoed by the county executive on a technicality, but will be reintroduced.

What were your main difficulties?

There were setbacks with a lot of labor-related legislation, such as mandating paid sick days for all workers and a county-wide neutrality agreement for union organizing campaigns. One of the difficulties of running as a third party candidate is the number of bridges burnt with sections of the establishment, including organized labor. I had a lot of support, but also a lot of enemies in high places because I am not a Democrat. So even if they supported the legislation, they might oppose things that I introduced. They thought this was some kind of strategy to get Progressive Dane to take over the county board. We spent a lot of time and energy on this and ended up feeling like it was wasted.

Obviously, another problem was that the next youngest person, after me, was decades older than I am! And being one of the only people of color on the county board was tough, because it was one more way to be attacked. It’s much easier for them to tag you as an “extremist” as a young person, or a person of color, and that was done over and over both inside the county board and outside of it. I was dubbed “Ashook the Kook” by a right-wing radio personality. During my two years, we sponsored some really controversial legislation – like replacing “Columbus Day” with “Indigenous People’s Day.” That exacerbated the ongoing attacks, isolating me and making it difficult for me to work with other county supervisors. Towards the end of my term, community groups would bring an issue to me and I would sometimes recommend they ask another supervisor to author it because it would have a greater chance of being passed.

The bigger issue is that we don’t have a strong, viable left-wing party in this country. The reality is that I had an uphill battle even during my campaign because there was so little left wing infrastructure.

So, with the lack of a strong Left, things are difficult even when we get somebody into office who’s a socialist.

Why did you decide to not seek re-election?

It was a tough decision to not run again. I figured that I had accomplished much of what I wanted to accomplish. You know, it’s funny that you ask this. I was asked this question in another interview and I told them that I felt more and more disengaged from the movement. The editorial board decided to run an article with the headline “I FEEL DISENGAGED”! So they turned it into something about me losing touch

with students.

But it’s really about being removed from organizing. By the time I had reached the end of the term, I was getting desperate and cut a few back-room deals. Even if they were small in scale, I felt that wasn’t the point. I wasn’t in office to just pass reforms, and thought that this wasn’t a good trend. Also, I needed to move away from Madison. A lot of people I’d known and who had worked on my campaign had left. I feel that I still would have won a re-election – in additional to my original base, there was probably more support I had won, especially financial support.

In the end I decided to not run again because I saw myself moving towards reformist work by the end of my term.

What are your final thoughts? Since you plan to go back to grassroots organizing, what can we learn from your experience in office?

When I came into elected office, organizing wise, I felt it would be a big boost to some of our strategies that hadn’t worked before. And, looking at some of the things we were able to pass, it was! Just recently, for example, we passed a “Sister County” agreement with a municipality in Venezuela – the first of its kind anywhere in the US since Chavez took power. With that, and everything else, we accomplished what we did because the people on the ground had a really strategic view of the way that power operates. Community activists and organizations understand how power works because they live under these power structures on a daily basis. That kind of organizing experiences helped a lot going into office.

But coming out of office, I have a whole different viewpoint of how power works within the structures that exist. I never really understood, I had a removed understanding of the State. I was talking with another elected official, a former Green who ran as a Democrat in Rhode Island. He told me that after serving in an elected office he understood the structures much better – but he also had far greater insight into people’s political motivations acting within them. The view of political maneuvering is far beyond anything I could have gotten had I not been in office. And now we can use that.

My friend Charlie always says – he said this before I got elected – “When you are in office, you should be like the guy at the water cooler, with all the information. Who knows all the stuff. People come to you and get information – you’re not the one that leads the struggle, but you can get the information out.” Now I’ve got the information, some of the knowledge and the experience, and I just want to distribute it to whomever can use it to organize!

Comments

7 responses to “A guy at the water cooler: Ashok Kumar talks about being socialist in public office”

I loved the article. I just randomly found this but I used to live in Ashok’s district. He really did have an immense amount of support but was continuously attacked by the media, business interests, and the political elite. I remember listening to the radio and hearing Kumar’s name come up all the time usually in the form of racist rants ..(http://podcast.loyalears.com/wtdy.php?task=browse&file_id=1804) like this one after he passed a law changing Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Great Article Isaac. I really enjoyed it!

When Ashok got elected, the County Board also shifted to the ‘left’ . Not to lessen anything Ashok was able to do, but he wouldn’t have succeeded without the changing balance of forces on the Board. Several conservatives were defeated and replaced by liberals. There was an uneasy liberal-left had coalition and Ashok pushed them all and mostly won.

The interview doesn’t mention a key reality. The County Board is nonpartisan. Ashok got endorsed by the Greens/PD/South Central LAbor Council but he didn’t run on a partisan ballot line. There was a steady/reliable PD minority for years on the County Board (Ashok won a district PD has controlled for many years) but when the additional liberal supervisors won, it created an opportunity and historic dynamic that Ashok was uniquely poised to take advantage of. Before 2006, no progressive would have ever expected to pass an impeachment resolution or address phone access for prisoners or expand Section 8 or create a sister county with Venuezuela -at the County level.

Ashok seized this historic opportunity. Because of his politics and focus he accomplished an incredible series of victories, in spite of the hatred on campus for him from the right.

He is awesome …. 🙂

Good interview.

This excellent summary of Ashok’s time in office, and on the possibilities and limitations of radicals taking local political office, reminded me of an article summarizing the experience of a comrade in Salem, OR, Bill Smaldone, who was on the local council there as an open “socialist/green”. Check it out

“Acting Locally” in the Age of Globalization: The Case of Salem

http://www.sdonline.org/34/bill_smaldone.htm

No, you’re right, I wasn’t making that narrow an argument about taking part in social activities. One could make a hella long and interesting list, including things like repairing grandfather clocks and going out dancing. And I thoroughly agree with you and your peeve.

I was just having that argument with an internet friend — about leftists taking power in a time of retreat — because I’d asked him what he thought about Nepal’s possibilities. I wish someone who was knowledgeable would write about that for this webzine. Or you could link me to some Maoist coverage — specific coverage, not just that general Kasama website.

How do you get actual paragraphs?! I hate that I can’t do that. Do I have to manually insert [br] using the triangular thingies, in order to have line breaks? I’ll experiment with that in this fairly short comment.

maeve66 is a middle school teacher in a working class suburb of Oakland.

A big paradox we’ve got is that socialists who have won office (in the state, or in their union) have an impressive vantage point of how power works. But because of security concerns, these experiences are usually not shared widely.

I have talked with socialists who, after being activists in the rank and file membership of their union (usually organizing “reform caucuses”) for many years, ran an slate to challenge the entrenched leadership and then and won office. Often, two things happen: first, the rank and file caucus, missing its key leaders, evaporates; second, the former “opposition” is now in the position of having to administer power during a time of retreat and incredible pressure to become reformist (and lacking a militant base to push things forward from below.) One question is, “is it ever too early to take power?”

When you scale this experience up, it is the heart of one of the big questions that has always vexed revolutionaries. Even on a global level, countries where the working class has a revolution in the absence of further revolutions find themselves isolated, the leadership becomes bureaucratized…

Second point I wanted to make (and I don’t think you were arguing this – but it reminded me of a peeve of mine) is that “operating naturally in the normal world” means a hell of a lot of different things within the working class. A lot of folks I’ve met think this means some strict adherence to “working class values.” To me that that seems like a big misunderstanding of the attempts by ex-student radicals to fuse with working class life in the 1970s.

Sometimes socialists get to thinking of them/ourselves as total aliens, and it becomes a self-fulfilling isolation. An important insight of the feminist and queer movements has been the incredible diversity of experiences and identities that are out there. At my last job, my coworkers were into, and often participated in groups around: building grandfather clocks, watching history documentaries, doing recreational mathematics, seeing live music and playing guitar, computer programming, playing on an international soccer team, reading about psychology, and on and on.

I think this is possibly the best thing that Solidarity has said about electoral politics this go-round. I appreciated your last thoughts about Obama-Clinton-McCain, etc… but I am heartily tired of debating Nader/McKinney when neither of them is going to generate the slightest interest among people who are new to socialism this time around. The buzz for independent politics this national election will obviously be lower than ever. I still think that we should work on the ground where we are active in the Greens, yes. But debating supporting every single independent socialist ticket, and wringing our hands about who will have a higher profile, Nader or McKinney? Ugh. Also, I am so tired of hearing the retreaded argument that “when the Democrat wins, people will become disillusioned that he doesn’t fulfill his promises”. Bullshit. I’ve very rarely seen that lesson learned. If ever. I’m only saying rarely in case someone can point me to an example, because I can’t think of any, en masse, since the Populists. Not in terms of individuals, obviously that happens. I *do* think that third parties like the Green Party offer an alternative that throws politics-as-usual into question — when they or independent groups like them TAKE OFFICE, as Ashok did.

So I’m glad that you chronicled a local experience with a very specific dynamic and very specific, concrete gains. Among the lessons that seem evident here are some ones that might seem so obvious as to escape comment: 1) we should do this where we can. We should try — IF we have an activist base and local credibility, and not otherwise — to get elected to local positions, for both propaganda and actual ameliorative purposes. 2) It’s a damn good idea to be able to operate naturally in the normal world, whether that is membership in a frat, or being on your local PTSA, or defending local libraries from budget cuts, or (well, I probably won’t be doing this, but all y’all should) joining city sports leagues, be it bowling or softball or soccer. 3) Oh, man, I am so impressed that Ashok was self-aware the entire time and could FEEL the reformist impulse getting stronger. That seems like an almost heroic struggle against Marx’s “being determines consciousness”.

maeve66 is a middle school teacher in a working class suburb of Oakland.

I think this is one of the best discussion pieces I’ve seen on the webzine yet. Big thanks to Ashok and Isaac for putting this together! (I like this version even better with the helpful “Know your Ashoks!” diagram, which will certainly clear up a lot of confusion in the Left)

One very helpful thing that this does is to move the discussion about electoral office from (sometimes very abstract) national independent party-building initiatives to the reality of taking (some) power and how to act appropriately. While the former process may be worthwhile, it is almost always limited to perpetual base-building around an objective that (under present and near-future conditions) will not be won. Like Maeve66, I get tired of this too.

The latter situation, what Ashok and others have gone through, offers much more fruitful experience for discussion, debate, and critical reflection. It really is a shame that (due to the security concerns Isaac mentions) we can’t broadly analyze these in depth. I’m a person who isn’t too familiar with precedents, which is another reason I appreciate the work Ashok and Isaac have done here.

What I found really interesting was how Ashok concentrated on using his position to open wider the potentialities for organized “mass” action. He attempted to create conditions where people could come out and push public debate in a progressive direction, as he explains about the local sheriff. I see this as a more creative use of local power than simply operating “by the book,” having your hands tied at every turn. Even when things were tried “by the book” (like creating new laws) it seems a lot of creativity was offered in introducing measures that were on the leading edge nationally (like the Dane County ID proposal). This shows me how occupying elected positions can potentially give us the leverage to go on the offensive–and even when this doesn’t work, it IS much, much better than defensive measures that don’t work.

Of course, we also need to keep in mind the caveats Isaac mentioned, like that of maintaining leadership in the “movements” outside of elected/administrative officialdom and keeping an organic link between these leaderships and those who win positions of power. By organic, I mean the importance of having leadership being rooted in these movements, having a history of active involvement in oppressed communities, etc.

I would like to say more about what happens when we “scale this up” to bigger electoral fights, but think I’ve typed too much already. I’m eager to see what others have to say about this very good piece! Thanks again y’all!