Jim Naylor

Posted June 7, 2021

As someone who has written about the history of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and the New Democratic Party (NDP), I’ve been intrigued by the recent discussion on this site of the CCF/NDP and of the British Labour Party (BLP). I agree that each provide lessons relevant to debates in Solidarity and the DSA. So far contributions have been well informed, although I think I can contextualize Canadian developments in a manner that will move the discussion along.

The Canadian and British cases are closely connected. Discussions of program and strategy in Canadian socialist circles tended to reference British developments much more than they did those in the U.S. Large scale migration of British workers to Canada early in the twentieth century led to close and ongoing connections to British socialism and particularly to the British Independent Labour Party (ILP). The discussion so far has referenced the ILP’s role in establishing the BLP, but it persisted as an explicitly socialist organization within the BLP and, following World War I, moved leftward.

In 1929, the British Labour Party, led by Ramsay Macdonald, formed a minority government just as the Great Depression was starting. The BLP proved incapable of confronting the crisis, introduced deep austerity measures, and then ceded power to an all-party “National Government.” Not surprisingly, the BLP was decimated in the next election.

The ILP, which had already been reassessing socialist strategies, disaffiliated from the BLP and, internationally, led in the formation of the “3 1/2 International” or “London Bureau,” a regroupment of socialists to the left of the Second International such as the German SAP and the POUM in Spain. Politically, Trotsky considered the London Bureau a centrist formation, straddling the boundary between reform and revolution.

These events in Britain occurred on the eve of the formation of the CCF in 1932-33. The new CCF identified closely with the ILP, generally sharing its critique of the reformism and bureaucratism of the BLP. CCF provincial newspapers followed the British events closely, regularly reprinting articles by ILP (and London Bureau) leader Fenner Brockway. CCF libraries, through the 1930s, were dominated by British writers from various left formations — debates in the old country provided much of the lens through which CCFers understood Canada and the world.

The CCF itself was a complex organization. It had no direct membership; rather, it was a coalition of labour, socialist, and farmer organizations, each with their history and politics. Within this mix, it was the socialist organizations in industrial centres, particularly Toronto, Winnipeg, and Vancouver, that provided both the organization spark and political identity of the CCF. And, although it included non-working-class affiliates, the CCF’s immediate roots were in the post-World War I labour uprising (including the Winnipeg General Strike).

The federated structure of the CCF was rooted in the determination of the founding socialist parties of the CCF to preserve their own working-class organizations through which they could provide class-conscious leadership to the larger movement. Significantly, the CCF denounced the Communists’ turn to the Popular Front in 1935 as the abandonment of working-class principles and politics.

In the 1930s, the CCF experienced considerable success, including electorally. Still, the decade was one of working-class defeat in Canada. Unemployment, of course, decimated unions and, unlike the U.S., the CIO organizing drive was effectively defeated. The outbreak of war in 1939 derailed the CCF in other ways; membership slipped sharply. However, wartime conditions resuscitated the union movement.

In 1943, one in three of all Canadian workers went on strike. There was no no-strike order in Canada, largely because Canada had no equivalent of the U.S. Wagner Act which provided a degree of union security and required employers to bargain. As workplaces organized and as demands for such legislation grew, the CCF was the clear beneficiary.

Along with growing hopes for a more equitable social order after the war, CCF membership soared. In the large industrial province of Ontario, for instance, CCF membership grew from 1,600 to 20,000 during the war; in the 1943 provincial election, the CCF came out of nowhere to win 32% of the vote and elect 34 members of the provincial legislature (largely trade unionists), just four seats short of the governing Conservatives. Nationally, the CCF edged out the two bourgeois parties in opinion polls.

Although the strike wave was the result of a groundswell of working-class militancy, it was generally not, as had been the case in the World War I era, a rejection of the existing union leadership. Union leaders had every reason to support Wagner-type legislation which secured their unions without challenging their leadership.

The Canadian Confederation of Labour (which represented, mostly, CIO unions in Canada) readily endorsed the CCF as “the political arm of labour” in 1943. The CCF became much more akin to the British Labour Party, both in terms of its organic ties to unions and in its politics. That identification was further encouraged by some of the gains that British Labour was able to achieve when they won power in 1945, such as socialized health care.

Many of the thousands who joined the CCF in the 1940s did so based on the British model and had little of the socialist education that had been central to the purpose of the CCF in the 1930s. For many longtime members of the CCF, this growth came at the price of the abandonment of anticapitalism as the CCF understood it in the 1930s and of increasing the weight of union officials in the party.

So, what is to be learned? First, in the 1930s, socialists who led in the building the CCF prized working-class political independence. The Liberal Party, which governed Canada after 1935, varied in character across the country, but even in places such as British Columbia where their “progressive” wing dominated and echoed U.S.-type New Deal policies, the CCF not just maintained their independence, but was able to counter the allure of capitalist reform quite successfully in provincial elections.

Secondly, when class conflict picked up again during World War II, the CCF was in place to attract those looking for a means to fight for working-class rights against Liberals who had, historically, promised much and delivered little.

It must be added, though, that the specific character of the wartime radicalization remade the CCF quite fundamentally. This, of course, is to be expected; any social mobilization will create structures appropriate to its composition and goals. (As an aside, I would argue that this earlier transformation reshaped the CCF more fundamentally than the somewhat orchestrated renaming and reorganization of the CCF into the NDP in the early 1960s).

How all of this is relevant to the debate underway in the U.S. requires an assessment of specific contexts and possibilities there. Still, Barry Eidlin, in Labor and the Class Idea in the United States and Canada (2018) argues that, whatever the shortcomings of the CCF/NDP, it kept alive a popular consciousness of class and contributed, for instance, to the much higher union density in Canada today.

As a corollary, it contributed greatly to the growth of the welfare state, while at the same time it participated in running that state with often less than stellar results. Socialists in Canada, of course, have been arguing about the NDP throughout its existence.

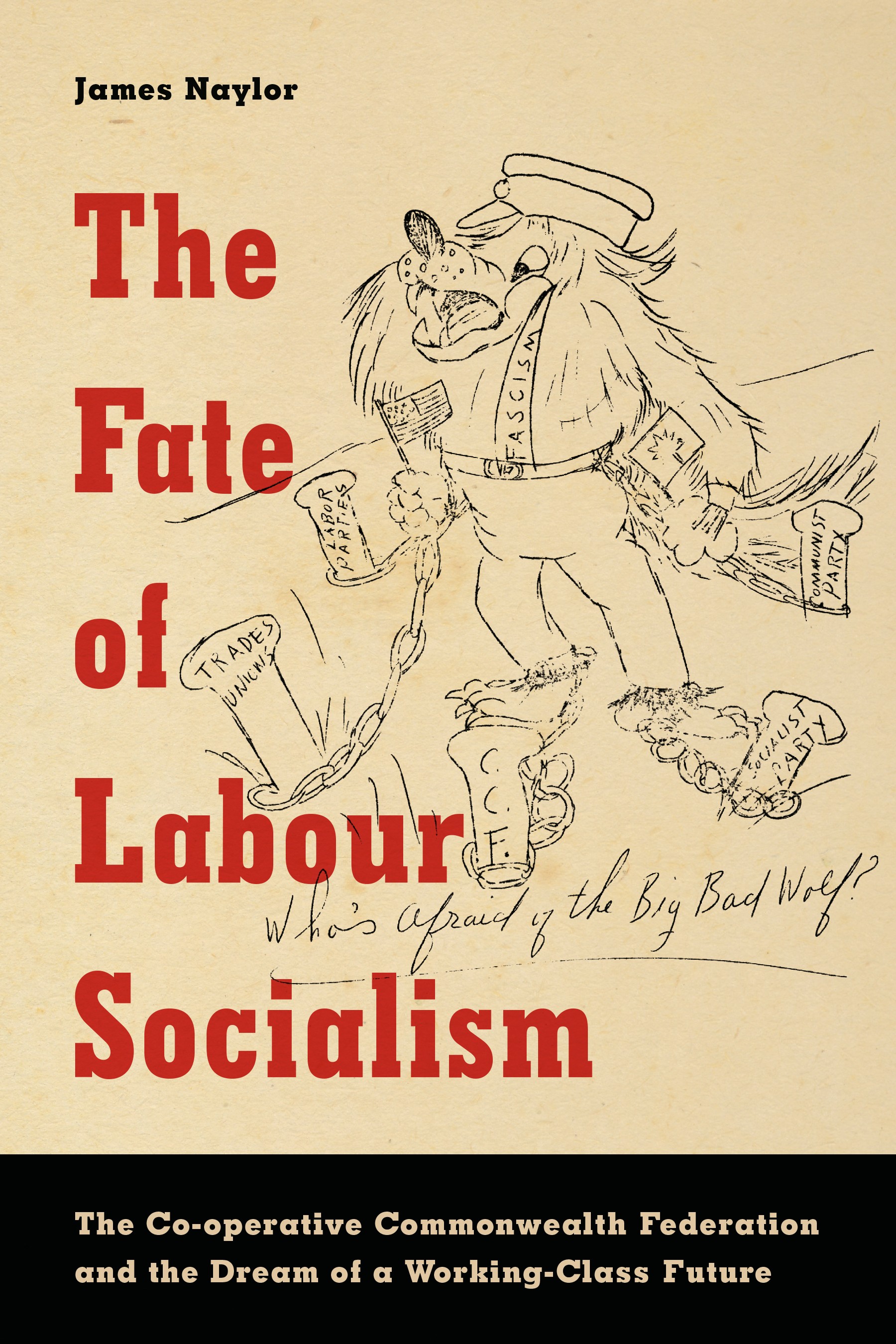

Finally, these short comments about the CCF in the 1930s and 1940s naturally simplifies much; anyone interested can find more in my The Fate of Labour Socialism: The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and the Dream of a Working-Class Future (2016).

Jim Naylor teaches History at Brandon University in Manitoba.

Comments

2 responses to “Clarifying the Canadian Example”

Please add something about relation of CCF with Social Credit Party.

The answer to your question largely revolves around the CCF’s reaction to the popular front.

For those who are unfamiliar, Social Credit was one of a range of movements that emerged in the 1930s as a response to the crisis of capitalism. It considered the source of the Depression to be ongoing shortage of consumer spending power and proposed a monetary dividend be paid by the state (“social credit”) to citizens. Led by radio preacher “Bible Bill” Aberhart, the Social Credit Party won the 1935 election in the province of Alberta, defeating a “United Farmers” government. The promised dividend never materialized, and the Social Credit government became increasingly right wing and authoritarian.

Beyond Alberta, Social Credit gained little traction. However, events in the neighbouring province of Saskatchewan raised interesting questions about CCF strategies.

The CCF generally dismissed the economic panacea that Social Credit offered, and third-period Communists panned them as incipient fascists. When their strategy shifted however, the CP changed their tune and sought to attract Social Crediters as popular front allies. This had little effect in Alberta where the Social Credit government effectively controlled the movement. However, Social Credit began to take off in in Saskatchewan, potentially challenging the substantial organization that the CCF had built. At the same time, a considerable segment of the CCF was open to participating in a version of the popular front. The CP-inspired “On-to-Ottawa Trek” of unemployed workers had won broad support – particularly in the provincial capital city of Regina where it was violently suppressed by police. In the same city, the CP and CCF (against CCF policy) cooperated in a very successful municipal election.

At the same time, some CCFers were sympathetic to the CP’s new attitude to Social Credit. Feeling that Social Credit’s appeal challenged the dominance of finance capital and that it was counterproductive to directly oppose them electorally, the CCF cooperated with Social Credit in a few constituencies around the province. However, this movement toward a de facto popular front was short lived. The alliance with the Communists in Regina soon fell apart, and clear right-ward trajectory of the Alberta Social Credit government undermined any potential co-operation anywhere.

This was an interesting moment with its own lessons. Both the CCF and the Popular-Front era Communist Party were interested in building broader movements within which working-class based parties would remain dominant. The CCF very quickly determined that Social Credit was rapidly evolving into a deeply antisocialist movement and they noted that the appeal of Social Credit beyond Alberta was rapidly fading. The Communists continued to speak of them as potential antifascist allies, but with little success.