Dan La Botz

Posted February 10, 2024

The article below is based on notes I prepared for my part in the Marxism List Forum held on February 3, 2024, on the subject of “The New U.S. Labor Movement: An Update on the Resurgence of Labor in the United States,” where I spoke with Bill Fletcher, Jr., and Eric Blanc.

The video of the panel can be found here.

The labor movement in the United States is passing through a transition from the stagnation of the period from 1980-2010 to a new period of dynamic change in industrial decentralization, new technologies, work, organization, union activism, and the enormous and enveloping issue of climate change. The new labor activism has been accompanied by new social movements, from Black Lives Matter to the new Palestinian solidarity movement. At the same time, the far right has been actively fighting progressive ideas and policies, from local library and school boards to judicial appointments and elections at all levels. Led by Donald Trump and his political allies, they are preparing an executive and legislative program to suppress the rights of workers, minority groups, women, LGBTQ+ people, and immigrants. So, this moment opens both progressive possibilities and reactionary dangers.

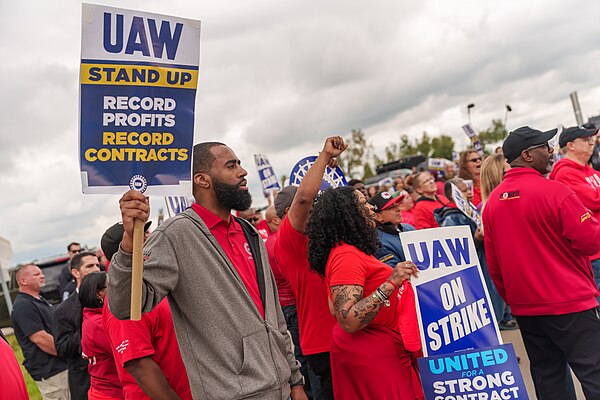

A New Era of Strikes

The last few years have seen a resurgence of strikes in the United States, beginning with teacher strikes in 2019 and culminating last year in major strikes by actors and writers in the movie industry, the health workers strike at Kaiser Permanente, and the United Auto Workers strike against the Big Three carmakers. In 2023, we saw a real strike wave. According to Barron’s, there were 400 strikes involving 400,000 workers. As Kate Bronfenbrenner wrote, “not only are more workers striking, but more unions are winning, and winning big.” These strikes are very significant, though they are still a far cry from the last great strike wave of 1970.

Workers have also carried out short strikes and brief walkouts at Amazon warehouses and Starbucks coffee shops, where there are ongoing organizing campaigns. Workers of all sorts have begun to engage in strikes against their employers, so that we can say we have in the United States the beginning of a return to open class struggle.

Women have played a central role in the strikes of teachers, health and hospital workers. And Black and Latino workers have been important local leaders and activists in strikes of both industrial and service workers. While racial and gender tensions are rife in our society, they do not seem to have so far inhibited joint workers’ action, though racism and sexism continue to exist in many workplaces and in some unions.

The strikes are not only for labor’s usual demands of higher wages, better conditions, and health benefits, but also defensive measures against technological change, whether AI in the movie industry or electronic vehicles in the auto industry. Other groups of workers, such as Los Deliveristas Unidos, are organizing among the 65,000 delivery workers in New York City whose work is controlled by electronic platforms. Nurses have been fighting for higher staffing levels in hospitals and clinics that have been transformed by technology, which has reorganized their workplaces. Yet, these strikes are taking place only among a small proportion of the working class. Today, unions represent only 6% of all private-sector workers.

The New Labor Leaders — A Mixed Bag

Some of these unions, like the UAW, have had rank-and-file caucuses that fought for changes in the leadership and pushed for these strikes. The strikes and the words of leaders such as Fran Drescher and Shawn Fain, who discuss strikes as demonstrations of “working-class power” against the corporations and “the billionaire class,” suggest that not only is there a break with the passivity of U.S. unions for the past 50 years, but also a change in rhetoric that may contribute to a change in class consciousness. Shawn Fain says that the UAW will “organize like hell” among the as-yet unorganized auto companies such as Tesla and Toyota. He has also called for all unions to synchronize their contracts to expire on May 1, 2028, to make possible a national general strike. No union leader has talked about such things for more than 100 years.

In the Teamsters, on the other hand, union president Sean O’Brien gave militant speeches, and with the backing of Teamsters for a Democratic Union, Labor Notes, and the Democratic Socialists of America, was hailed as a reformer and a militant. But he preferred to reach an accommodation with UPS that failed to resolve the issues of part-timers but avoided a strike. Many rank-and-filers and leftist union activists were disillusioned and disappointed by O’Brien. All of this opened up space for a new opposition group made up of a small number of leftists and rank-and-file UPS workers in a new dissident group called Teamster Mobilize.

In any case, whoever leads the unions, we should remember that the labor bureaucracy, especially at the highest levels of big city, state, and national officials, constitutes a social caste with its own interests and ideology. Labor officials often enjoy a privileged situation economically and socially compared to the workers they represent. The officials, based on their social position where workers, bosses, and government intersect, tend to believe they know what is best for the working class. In reality, they face pressures from both employers and workers, and most attempt to placate both. Some even become the employers’ disciplinarian of the workers, enforcing the no-strike for the life of the contract pledge found in most contracts. Rank-and-file organizations are necessary to put forward militant leaders and keep them on the workers’ side.

Unions and Politics

Most unions and most workers usually support the Democrats because they believe the Republicans would be worse. Union leaders also prefer the Democrats because the politicians’ backing can represent an alternative to rank-and-file mobilization, especially in the public sector. Many unions and their leaders have a longtime and intimate relationship with Democratic politicians and believe they have leverage with this, though it is often difficult to demonstrate the benefits.

President Joe Biden, in a first in U.S. history, went to a UAW picket line where he spoke in favor of the union, as had Senator Bernie Sanders. Not surprising, then, that Fain and the UAW executive board have endorsed Biden for president, though there was no union-wide discussion, meetings or vote. Many UAW members are politically conservative. An internal UAW poll conducted last summer showed that 30% of members supported Biden, 30% backed Trump, and 40% were independent, that is, voters who sometimes support the Democrats and sometimes the Republicans. The great majority of unions endorse Biden, but the rank-and-file members of the building trades largely supported Trump in 2016 and in 2020, and most still do. The same is true of other white industrial workers in unions, such as the United Steel Workers. Teamster leader Sean O’Brien, who has glad-handed a number of far-right Republicans, recently went to Mar-a-Lago to meet with Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, angering some members. But O’Brien’s remarks after a recent meeting with Trump, at which the Teamster leader praised Biden’s accomplishments, suggest that meeting with Trump was a sop to his union’s Trump supporters and that, in the end, the union will endorse Biden.

Worker militancy, even when accompanied by an incipient class consciousness, does not necessarily correlate with radicalization or a leftward-leaning politics. With the vanguard of the current labor militancy, the UAW, endorsing Biden, and with many rank-and-file workers mesmerized by Trump, there is little chance of some new progressive political development in the working class. While many on the left would like to see the creation of a Labor Party, there is not even any serious discussion of such a development in the unions. The Green Party, the largest and most significant left party in the country, on the ballot in most states, has virtually no following among unions. Its presidential candidates usually receive about 1 to 2 percent of the vote nationally. An independent candidate like Cornel West has just begun to organize a new political party, but, so far, his name appears on only two state ballots. Most unions and progressive workers find the threat of Trump’s authoritarian, quasi-fascist politics too threatening to vote for a third party.

The Left in the Unions

There are hundreds of young radicals active in a number of unions — nurses, teachers, the UAW and the Teamsters, for example. Some are members of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), and others are members of some smaller socialist groups. Some of these leftists work with Labor Notes, a newspaper, a website, and an educational and training center that works to further union democracy, militancy, solidarity, and internationalism. Both DSA and Labor Notes have worked to establish networks of rank-and-file caucuses, such as those in the teacher’s union. Still, the left in the unions is not large enough or coherent enough to actually lead any important unions or workers movements.

The left in the unions is generally in favor of more militant action, but also sometimes raises other issues. Many leftists in the union made efforts to involve their unions in the Black Lives Matter movement. Some leftists in the labor movement work to involve the unions in developing policies that can become legislation to deal with climate change. They mobilize union members, for example, to join the climate marches. For decades now, partly thanks to the left, many unions have developed strong positions for women’s and LGBTQ+ people’s rights.

Most recently, some union activists have expressed support for a ceasefire in Israel’s war on Gaza, and some UAW members spoke out at the union conference and voted against endorsing Biden, who continues to provide arms to Israel. As the popular leader of his union, Shawn Fain has been able to call for a ceasefire and show support for the Palestinians. Not all union activists are in a position to do so. The ceasefire and Palestine solidarity positions taken, for example, by teachers’ unions in the Bay Area, have proven divisive in the union and in the community. Raising such issues requires a base in the union, education on the issue, and finesse. Unions that passed such resolutions have been accused of anti-Semitism and have not been prepared to rebut such false accusations.

The Possibility of a Labor Upsurge and Radicalization

Leftists have historically looked to economic crises to detonate mass working-class struggle, often exaggerating the possibilities of a crisis and expecting an automatic and immediate response from workers. No such crisis has occurred since the Great Depression of 1929, almost 100 years ago, and the workers’ reaction then took at least four years to begin then. Today, we have no such crisis. While many Americans perceive that the economy is weak, there is little basis for this in fact, and the situation is not dire for most working-class people. While there is a lot of economic inequality in the United States, and it is growing, and a good deal of poverty, we are not now in an economic crisis such as the 2008 Great Recession caused by the bursting of the housing bubble or the 2020 crisis that resulted from the COVID pandemic. And neither of those produced a worker upsurge.

The economy revived and remains strong, with high levels of profitability, higher wages, and the lowest unemployment in decades. Inflation — at the cost of some jobs and wage gains — has been brought under control by government policies. As usual, the situation is worse for Black and Latino workers. On the other hand, when the economy is strong and there is low unemployment, workers often feel they can make bigger demands and take action without fear of being fired and unable to find a job. So, there is little likelihood that the current economic situation will in the short-term precipitate an upsurge and radicalization of labor — though we also know that crises can erupt suddenly, as they have done repeatedly in the last forty years, such as 1981-82 and 2007-08.

Or Perhaps a Political Crisis

We could also imagine, however, that a political crisis could affect the working class. Since Trump’s refusal to concede his defeat, accompanied by a four-year campaign of lies and agitation, as well as the insurrection and attempted coup of January 6, 2021, there has been an underlying political instability in the country. The right has mobilized around issues of gender and race at school and library board meetings, and has also targeted teachers and librarians. A serious political crisis is likely should Trump lose the election, leading to violent responses from his followers. How the unions would respond to such a development remains unclear.

If Trump, on the other hand, should win, he and his advisors are planning to reorganize the federal government, doing away with laws and regulations that protect workers’ rights, the rights of racial minorities, women, and LGBTQ+ people, and that provide social benefits. All of this is laid out in great detail in the Project 2025 policy agenda titled Mandate for Leadership. Our existing civil rights, labor law, and whatever remains of immigration protection would be erased. One can see these changes as taking us back to the 1950s or even the 1920s, or forward into a new authoritarian regime on the way to fascism.

If Trump is elected, the working class could well be faced with an authoritarian government and repression, such as we haven’t known for decades. We should remember that during World War I, Woodrow Wilson’s administration suppressed the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World, and that the army, police, and the American Legion destroyed union and socialist halls and print shops, and large numbers of leftists and labor activists were beaten, imprisoned, and a few killed. Also, recall the Smith Act trials of 1941, when the Trotskyist Teamster leaders in Minneapolis were tried, convicted and imprisoned. And the McCarthyist period of the 1950s, when many Communists were jailed, left-led unions repressed, and workers fired. Unions were not able to stand up to the repression either in the 1920s or the 1950s. Once again, how the union movement will react in such a case remains to be seen. We don’t know whether such a repressive environment would lead to mass labor action or to a new labor radicalization. In any case, we should have our eyes wide open as we go forward.

The left’s agenda, then, despite the unique character of the moment, remains largely the same as it has been for some time. Organize rank-and-file workers, organized and unorganized, into a militant class-struggle movement, ally with Black, Latino, women’s, and LGBTQ+ movements to fight the right wing’s racist, sexist, and anti-working-class agenda, work with the climate justice movement to fight climate change, and build an independent political movement. We have a lot to do.

This article originally appeared on the New Politics website on February 5, 2024, here. We’ve corrected some typos, but the article is otherwise as it appeared there.