K Mann

Posted July 18, 2019

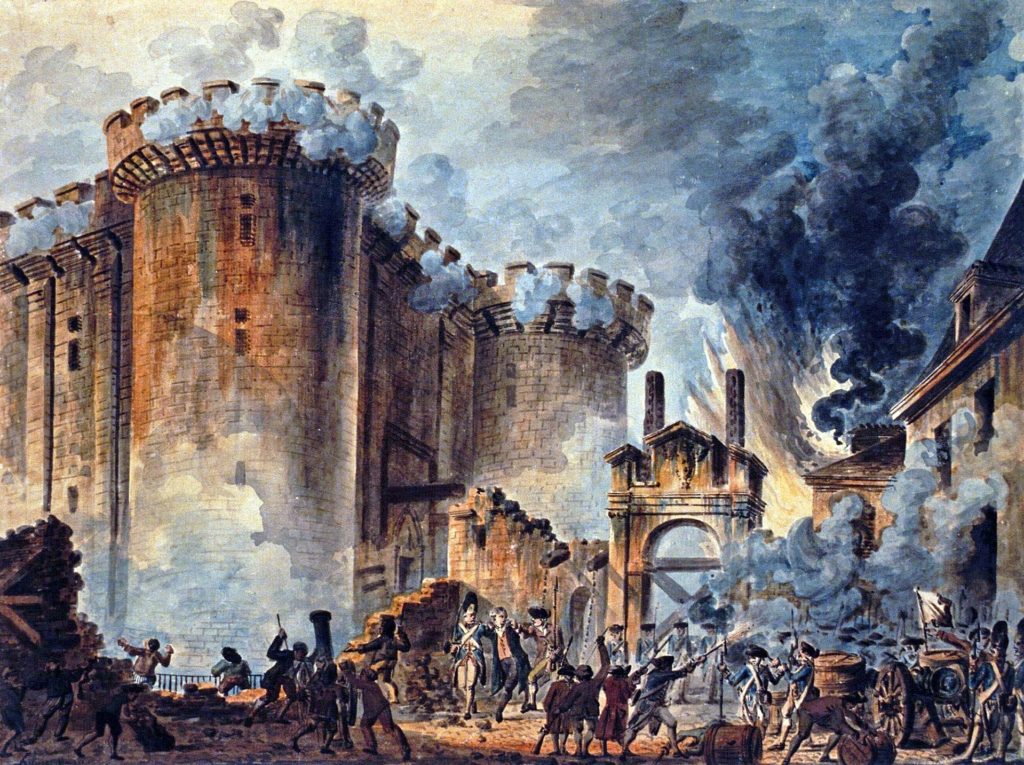

“The Storming of the Bastille,” by Jean-Pierre Houël, at the National Library of France

This year marks the 230th anniversary of the beginning of the French Revolution of 1789. The storming of the Bastille by an angry crowd of Parisians on July 14 of that year has always been the chief symbolic event of the French revolution. For good reason: the Bastille, a fortress in Paris used as a prison, was a symbol of old regime tyranny. But the attack on the Bastille including the freeing of its seven prisoners, the killing of the resisting officer in charge, followed by the stone by stone dismantling of the fortress was not only symbolic. The audacious attack on the fortress – royal property in the heart of Paris – marked one of the first direct entries onto the political scene of the people of France. The more astute representatives of Royal power sensed this was a grave turn of events. When asked by Louis XVI if the attack on the Bastille had been a “riot,” the king’s Minister the Duke de La Rochefoucauld replied, “No sire, it is a revolution.” Indeed, the entrée of the people onto the scene accelerated the revolutionary process.

Up until that point, the revolution had been largely an elite affair. The revolutionary process began as the political representatives of the three “estates” the clergy, nobility, and commoners assembled in nearby Versailles to bargain with the Monarch in the spring of 1789. That was a significant affair in its own right; the French monarchy had been powerful enough not to call representatives of the three estates over the previous century, a feature of the absolute rule of the crown. However, by the late 1780s, Louis XVI’s monarchy found itself badly in debt -– largely the result of a series of costly wars aggravated by expensive sinecures and government contracts doled out to royal favorites. As a result, the crown felt obliged to summon the representatives of the three estates in order to bargain over the terms that they might agree to in exchange for increased taxes. This set the stage for a series of skirmishes between the estates and the monarchy, fissures between and within each estate delegation, and an ensuing opening for the people of France and particularly Paris to begin the reordering of society on a more egalitarian basis.

Throughout France, assemblies had been held to choose delegates to the Estates General. During these meetings, cahiers de dolances or grievance notebooks were drawn up. The cahiers recorded the misery of the peasantry and laboring classes, and their resentment and anger toward their royal, aristocratic, and bourgeois oppressors, But it was the direct mobilizations of the popular classes themselves and the accompanying questions of popular democracy that followed, that are the heart and soul of the French Revolution and have particular relevance for socialists today.

The sans-culottes

Historical evidence suggests that the crowd that took the bastille corresponded to the amorphous non-aristocratic, non-bourgeois masses of Paris. Artisans, journeymen, apprentices, domestic workers, and unskilled day laborers were all united by concerns about the cost of living. These were the sans-culottes, (a reference to the breech-less pants worn by laboring men, in contrast to the knickers worn by the bourgeoisie and aristocracy). The sans-culottes were both a political and social designation. They were united as consumers rather than as wage workers, reflecting the pre-capitalist nature of France’s economic and social structure at the end of the eighteenth century. Their egalitarian, anti-monarchical political orientation and sustained political involvement was the political part of the san-culottes designation. In Paris and elsewhere, the sans-culottes and popular classes flooded into sections, clubs, and numerous public forums of debate and discussion. As they did so, natural leaders emerged and wide political consciousness and sophistication rose. Neither tradition nor law kept women from fully participating in this movement.

At various key moments the sans-culottes took direct action to assure the survival and deepening of the revolution and press their own demands – such as price controls for bread. On October 5, 1789, only several weeks after the storming of the Bastille, a contingent of approximately 7,000 mostly women sans-culottes, some armed, marched from Paris to Versailles, the royal palace where the French monarchy had lived since the time of Louis XIV in the 17th century. They demanded bread and the return of the royal family to Paris. The next day the women accompanied the royal family against its will, to its Parisian palace, the Louvre – a stunning victory for the popular movement over the monarchy.

Over the next several years, a series of urban uprisings by the sans-culottes, referred to by French historians as journées, pushed recalcitrant national legislative bodies forward. The pitched battle between an armed royal contingent and thousands of sans-culottes backed up by revolutionary contingents from Marseille and Brittany on August 10, 1792 in the gardens of the Tuileries adjacent to the Louvre, was a precipitating event in the fall of the monarchy.

As the forces of European reaction prepared military intervention against the revolution, the sans-culottes enthusiastically joined the revolutionary armies. These poorly trained but highly motivated “citizens’ armies” scored impressive victories over the much better trained professional armies of Austria and Prussia who were intent on overthrowing France’s revolutionary government.

Radical Demands Provoke Counter-Revolution

Popular power increased for the first three years of the revolution and peaked around 1792-93. As it declined, so did the most radical and egalitarian aspects of the revolution. The radical lawyer, Maximilian Robespierre, a prominent member of the Jacobin political clubs and the most powerful member of the revolutionary government’s executive body, the Committee for Public Safety, drew on popular support in his struggle against the more moderate Girondist political grouping and others to their right. But when the popular classes insisted on price controls for bread and basic necessities, he took measures to suppress organs of popular political participation. Having demobilized the popular movement, Robespierre was unable to rally mass support in his showdown with his political opponents, which led to the fall of his government and the guillotining of him and his closest associates in July, 1794. By the time that General Napoleon Bonaparte gave the revolution its coup de grâce in 1799, the French masses had been long cast to the sidelines.

The 19th century saw the birth of socialist and labor movements in France, Britain, the US and elsewhere giving the working masses a direct entry onto the stage of national and international politics. The rise of unions and working-class political parties, and a slowly expanding male suffrage – women had to wait until well into the twentieth century – signaled the entry of working people onto the stage of national and international politics. In France, the tradition of popular mobilization that figured so prominently in the French revolution was revived after the Napoleonic period. The revolutions of 1830, 1848, and the Paris Commune of 1871 all featured popular mobilizations that were decisive in toppling governments. The Paris Commune saw particularly bold experiments in direct democracy like instant recall of elected officials upon majority vote.

Festivals of the Oppressed

Revolutions, it has been, said are “festivals of the oppressed.” The feverish hunger and thirst of ordinary toiling people to participate in and control public affairs, and thus control their own destiny that we saw in the French revolution, is a fundamental feature of revolution and social movements in general. US revolutionary journalist John Reed, present in St. Petersburg at the time of the October 1917 Russian revolution, noted that passengers on an overnight train between Moscow and St. Petersburg formed a travelers’ soviet or council as they travelled between the two cities. More recently, we have seen this democratic impulse in social movements like the Occupy Wall Street movement in the US and elsewhere, which developed creative horizontal forms of decision-making. The yellow vest movement in France that began in 2018 has likewise developed highly democratic and egalitarian forms of organizing, including mandated gender parity.

Bastille Day celebrations in France have long been used by French governments to whip up patriotism and draw attention away from the glaring social inequalities in French society. Elaborate Bastille Day military parades, the envy of Donald Trump, give Bastille Day a narrow, nationalist character. Conservative historians and journalists never fail to use July 14 celebrations as an occasion to slander, co-opt, and otherwise obfuscate the revolutionary character of Bastille Day and the French Revolution. But as we look back to those turbulent times in 1789, socialists shine the spotlight of historical memory on the stunning and unceremonious entry of the people themselves onto the stage of history – perhaps the greatest legacy of the fall of the Bastille.