Dianne Feeley

Posted May 6, 2020

As the pandemic rages we realize that “necessary work” is not Wall Street and its stock market or the manufacturing of cars but the health and well-being of society. That is, the work that is central to society turns out to be what socialist feminists call “social reproduction.” These are the functions necessary to sustain human life, whether performed inside or outside the home, whether paid or unpaid. For the most part this has been considered “women’s work,” and if paid work, generally poorly paid.

In the midst of the pandemic, women are over-represented among workers deemed “essential” — 52% compared to 47% in the workforce as a whole. Of the 19 million U.S. health care workers, four out of five are women. At the lower end of the pay scale of the industry are 5.8 million who are working for less than $30,000 a year, with few benefits. Of those, half are people of color, 83% of the total are women. Shockingly, the Centers for Disease Control found that 73% of the health care workers who have been infected with the novel coronavirus are women.

With the governors of most states announcing “stay at home” orders, we see how vulnerable these “frontline” workers are. Whether grocery stores, nursing homes or hospitals, none of these workplaces are designed for emergencies. Rather capitalism’s latest and most vicious form, neoliberalism, has stripped these spaces of excess capacity. There is no extra stock in their pantries or warehouses and no excess staff if someone falls ill. Instead, the staff is expected to work harder and make up the difference. In fact, this just-in-time model was invented to find where slack existed and force its elimination.

Even now, at the height of the pandemic, as hospitals struggle to receive those who are too sick to stay at home with the virus, management is laying off hundreds of health care workers. As Trump remarked, when asked why he abolished the research team that was anticipating the next pandemic, as a businessman he didn’t like the idea of people just standing around.

Hospitals are unprepared for emergencies, because that is not where they earn their profits. John Fox, the CEO of the largest hospital complex in Metro Detroit — Beaumont Health — announced, at the height of the epidemic, that it is losing $100 million a month. This is primarily the result of having to reschedule lucrative surgeries and other outpatient procedures. Profitability, not the community’s health, is the bottom line!

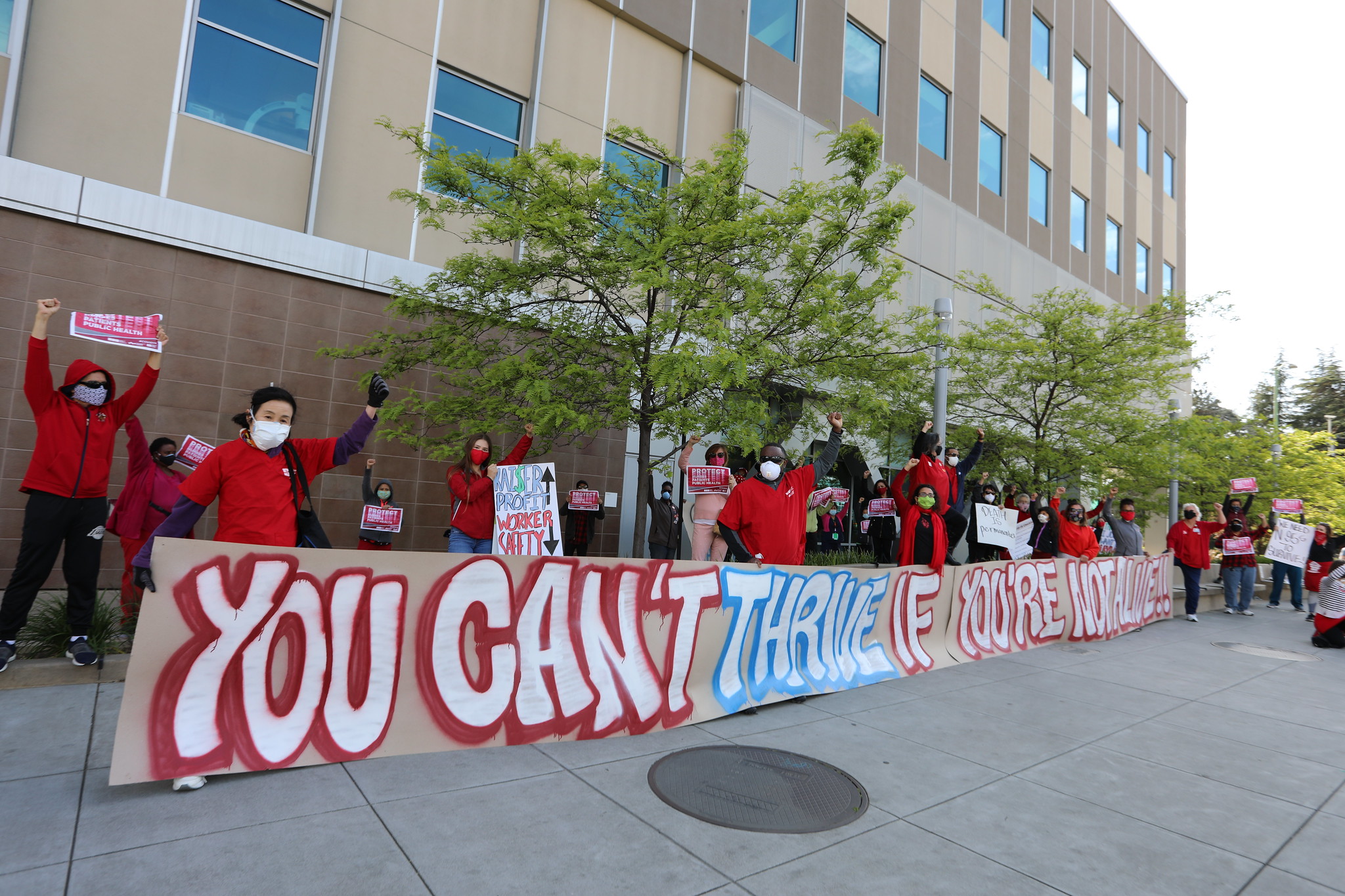

Lack of preparation leads to severe complications. That’s why nurses throughout the country have organized innovative protests — from gown-making parties, press conferences, socially distanced rallies to car caravans — against the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE). With a quarter to a third of the hospital staff quarantined with the suspected virus, these actions insist on mandatory safe staffing and that hospitals coordinate resources rather than compete.

Wildfire in Nursing Homes

In the case of the country’s 15,000 nursing homes with 1.5 million residents, the staff is 88% women, many of whom are African Americans or immigrants. Because the majority earn less than $30,000 a year, many pick up extra hours at more than one facility. Since they generally have neither sick pay nor adequate health insurance, when sick they are put in a position of staying home and losing their pay or going to work and possibly infecting already vulnerable patients. With even less access to PPEs than hospital workers, when they return home, they are less likely than hospital workers to have the space to isolate themselves.

Since lean production dictates understaffing, management generally urges them to come in. Although local governments regulate these facilities, under neoliberalism the regulations have been relaxed. This occurs through fewer on-site inspections; when inspections do occur, management is often informed beforehand.

In Detroit, where all nursing home residents and staff were tested, 25% tested positive, with half being asymptomatic. By April 20th, there were 124 recorded deaths. Particularly in New York City and New Jersey nursing homes have been so overwhelmed that bodies have been stacked up in garages. Reports are concluding that at least 20% of all Covid-19 deaths are nursing home patients and staff.

Perhaps now that the families of patients have raised the issue of how little nursing home staff is paid there will be greater awareness that the overwhelmingly female work force needs not only better pay, but safe working conditions and an extensive sick leave policy for starters.

Difficulties of “Stay in Place”

Eight out of ten homecare workers are women. Many have been laid off but do not qualify for unemployment. Many single women with children face not only financial insecurity but increased burdens of care in the home.

In addition to the usual household tasks, this includes working with their children on schoolwork. With schools closed and most day care reduced, mothers take on the bulk of childcare at a time when children have lost access to their friends and teachers. This is particularly difficult for women with disabilities or women whose children have one form of disability or another. It is also a problem for women when classroom learning is taking place online but there is no internet within the home.

Clearly, the pressure on women to care physically and emotionally for household members has increased.

Safety at Home?

Women have never been “safe” within their homes. Rather this space has always been a site of abuse, for women and often for their children. According to The Guardian (March 28). domestic abuse in Hubei province tripled in February and, as the virus spread to various European countries, rose there by 20-50%.

Every member of the household is suffering from the trauma of a pandemic: the isolation from one’s friends and relatives, from one’s daily schedule, from the requirement of continuously sharing one’s space, and fear of the unknown future. Under stress, a certain portion of men lash out at their women partners. With schools closed, violence against children, particularly children under five, is also likely to rise. At the same time, women and children have less opportunity to move away from the outburst or to tell someone what is happening.

Knowing that abusive behavior rises in moments of emergency, domestic abuse hotlines have publicized their willingness to help. They have found there are fewer phone calls but more text messages and use of email. However, some women’s access to cell phones have ended because cell phone plans are disconnected when household expenses have to be cut. Finally, the shelters’ ability to provide women and children with an alternative home is reduced in this moment.

The solutions to the pandemic cannot be a return to “normal” but a rebuilding of social solidarity. It not only means Medicare for All but viewing housing and education as rights. It means developing social networks that decrease the loneliness individuals face and increase their ability to make appropriate choices. It means prioritizing the reproductive work of society, placing greater importance on meeting people’s needs than on producing commodities.