Cyryl Ryzak

January 25, 2018

From October 22nd to the 25th, the AFL CIO held its quarto-annual convention in St. Louis, Missouri. The choice of city was, if not intentionally, appropriate.

Within St. Louis’ history is an extended case study of the American working class’ past militancy and current predicament. The great boom of capitalist development in the mid-nineteenth century caused a migration of workers from Europe and agrarian areas of the East Coast to the growing industrial towns of the American Midwest.

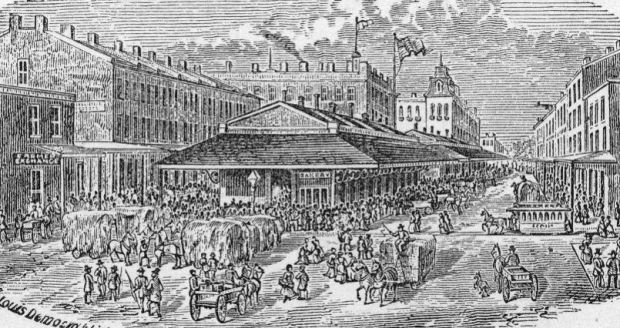

St. Louis strikers rally at Lucas Market Square

St. Louis strikers rally at Lucas Market SquareWhen this great boom came to a screeching halt, becoming the Long Depression of the 1870s, manic railway expansion across the United States came to haunt the bourgeoisie in 1877, as workers across the United States struck against the railway companies. In St. Louis, the railwaymen were joined by workers across industries in a General Strike that became an almost Paris Commune-type situation.

Fast forward to present, St. Louis reads as a characteristic case of contemporary American capitalism’s triplet blights: de-industrialization, urban collapse, and union decline. The former railroad hub’s fortunes fell with that mode of transport; employment in meatpacking and leather goods vanished. With the decline of these industries came the decline of unions. With decently paying union jobs gone, the small businesses which sold to St. Louis’ heavily black working class also went bankrupt. With both its workforce and circle of employers shrinking, the municipal authorities found themselves with a much narrower tax base. The authorities responded with austerity. Taxes went up and public services were cut. The combination of all these factors led to mass flight. The city’s resident population was halved between 1960 and 1990.

Given St. Louis’ character as a microcosm for neo-liberal pathologies as well as its historical symbolism, the failure of the labor movement to seriously challenge capital’s offensive in the final quarter of the last century was staring the delegates right in the face. In an alternative universe, the setting might have acted as further motivation to throw away failed strategies and begin to put an end to the erosion of worker power in the United States. There would be a certain historical justice if labor historians of the future could the write the words: “In St. Louis, a city ravaged by de-industrialization and urban decline, the AFL-CIO finally turned to the left and laid the foundations for a socialist labor movement which fundamentally transformed American society in favor of the working class.”

Growing Polarization within the Labor Movement

The actual course of events, unfortunately, did not conform to this fantasy.** If the history books pay any attention to the 2017 AFL CIO convention it will be as yet another stepping stone in the growing polarization between the emerging, yet still poorly defined left-liberal faction pushing for a more social movement oriented direction and a business unionist bloc.

The fragility of the federation was reflected in the attendance, reportedly lower than before. Unions no longer with the AFL-CIO, such as the ILWU, did not, of course, show up. Representation from Central Labor Councils was down as well.

The elephant in the room was the political situation, now substantially worse since the last convention in 2013. The Republicans have seized the Senate and the White House, and continued their almost unstoppable conquest of state government. The legislative horror of a National right to work law poses a severe threat, while the president staffs the Department of Labor and NLRB with anti-labor functionaries.

Above all, the most immediate threat to the AFL CIO is the Janus case. The incredible harm which this ruling would do to public sector unions would undermine the existing structure of the federation. Further, if the more parochial, conservative building trades pull out, the AFL-CIO would be reduced to a largely volunteer operation.

The slogan of the convention: “Join Together, Fight Together, Win Together” expressed the aim of AFL-CIO leadership: to keep the affiliated unions from breaking decisively. There were obligatory references to the need to organize and to the dire political straits in which unions have found themselves. Nobody, however, takes the rhetoric seriously. Despite the AFL-CIO leadership urging greater efforts at organizing in the 1990s and 2000s, the labor movement continues to suffer from an inability to break its weak position. AFSCME and AFT are focusing on internal organizing against National Right to Work. The recent failures to organize southern manufacturing were unacknowledged.

Labor’s currently defensive position, its almost total reliance on the survival of public sector unionism, is the product of a long decline. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, union membership in 2015 was

only half of the 1983 rate. But in 1983 it was only 20% of the labor force. Even in its supposed golden age in the 50s and 60s, after purging the labor left, American labor was afflicted with a syphilis of bureaucratic inaction, famously symbolized by George Meany’s claim that he never walked a picket line. This refusal to go beyond the confines of limited, legalistic industrial relations, a dependency on any Democratic Party politician no matter how right wing, and failure to organize outside of the urbanized Northeast and Midwest were the structural roots of labor’s current crisis.

The left-liberal wing took initiative at the convention to push for a more independent, social movement-oriented labor movement. Unfortunately the weight of conservative forces makes transforming a united AFL-CIO into an adequate instrument for class struggle unionism currently unimaginable.

Independent Political Action on the Agenda

Meetings held by Labor for Our Revolution, the carry-over organization from Bernie Sander’s labor supporters, and the APWU on the topic of a labor party were relatively well attended. On the other hand, despite the acknowledged need for labor to adopt some form of political action independent of the Democratic Party, no one believed labor had the ability to play a serious political role on its own.

The need for political independence was vaguely acknowledged by a resolution put forward by AFSCME calling for an end to a “lesser of two evils” politics. It was acknowledged that labor wins around issues not Democratic Party personalities. This resolution was offered as an alternative to a much stronger political independence resolution proposed by Mark Dimondstein, the pro-labor party leader of the APWU. In the end, both resolutions were passed together

The left pole of at the convention was anchored by the APWU and National Nurses United. The Nurses, who had boycotted the previous convention, were Bernie Sander’s main labor backer. Despite Sanders’ popularity, it was impolite to mention his name at the convention. Any accommodation towards even the soft left could not go too far.

A Step Forward for Medicare for All

The Left’s greatest success at the convention was getting a resolution passed in favor of Medicare for All which will enable single-payer organizing by labor on the local level. The Labor Campaign for Single Payer (LCSP) dominated the discussions surrounding healthcare. Coordinating with allies, LCSP had the mics at the convention covered, and were in tune with the sentiments of the majority at the convention.

NNU delegate Sandra Falwell speaks on single payer

NNU delegate Sandra Falwell speaks on single payer”

LCSP however faced a hurdle in the resolution committee which was packed with representatives of the building trades. The building trades, the main conservative force in AFL-CIO, wanted to concentrate on going after the Cadillac tax. Unions that have large Taft Hartley funds are concerned about how single-payer would affect their funds. In the end, however, the LCSP carried the day. The building trades chose not to block the momentum for single payer. Medicare for All gained the support of not only the APWU and the NNU, but industrial unions such as the CWA, UAW and the Steelworkers.

A Step Backward on Green Jobs

The success of the left in healthcare was not mirrored in efforts to push labor totake a stand on the environmental question. While a resolution was passed recognizing the problem, it lacked a sense of urgency. Moreover, a thorough policy addressing climate change by creating jobs in the clean energy was lacking. The Labor Network for Sustainability, which had advocated for a comprehensive climate change resolution,

criticized the approved resolution for its vagueness in formulating a “green jobs” creation policy.

On climate change, undoubtedly the victors were a conservative bloc composed of the building trades and the extractive industrial unions. The UMW, despite its militant tradition, from spearheading the CIO to the Miners for Democracy movement, stuck by their immediate interests in defending the coal industry from environmental constraints.

Challenges Facing Just Transition Politics

Unfortunately, the conservative stance of extractive industrial unions is almost inevitable. The left’s position hinges upon “just transition”–, that is, industrial policies geared towards promoting sustainable jobs which would match or improve the employment, pay, standards, and benefits of workers in industries detrimental to the environment. The problem, however, lies in the absence of any force capable of pushing for such a transition. The labor movement is too weak and the Democratic Party is disinterested. The Republicans in power are certainly not going to implement a just transition. It simply is far more pragmatic for the UMW to stick by their industry than bet on something that seems unrealizable in the short term.

The real tragedy is that just transition is the only hope for depressed coal mining communities. Even if environmental regulations were lifted, even if coal mining was more heavily subsidized, the only way for coal mining to survive as an industry in the face of growing competition from natural gases are drastic cuts in capacity. For coal companies to restore their profitability, there would have to be a massive wave of coal mining closures amounting to a loss of about 160 million tons according to a report from business magazine McKinsey Quarterly.

The environmental question demonstrates that workers only have two choices: the ecologically blind capitalism of the coal bosses, whose fraudulent appeals to miners mask the exploitative relation between them, or a socialist industrial policy based on just transition. This dichotomy corresponds with the fundamental issue at the heart of the labor movement’s growing polarization. Either the labor movement remains a federation of organizations who put the short-term interests of their respective industries first or it becomes a movement for social transformation in the interests of all workers.

Underneath the Complacency A Progressive Force Begins to Stir

The 2017 AFL-CIO convention did not resurrect the spirit of the St. Louis general strike; but ,while this was not the decisive battle, there were some signs that the future belongs to an emerging left. The victory on healthcare and the fact that the leadership was forced to acknowledge climate change and pay lip service to independence from the Democratic party in very watered-down resolutions show that the tide may be turning. The convention may have been a depressing ritual of self-affirmation in the face of an increasingly grave predicament, but underneath the complacency, a progressive force begins to stir.

Cyryl Ryzak is a member of Solidarity in Portland, Oregon.

** Interview with a delegate, Traven Leyshon, whose firsthand account of the convention was indispensable for this article and whose edits saved the author from the sin of journalistic exaggeration ↩