Bayla Ostrach

December 8, 2017

New York Coalition for Human Rights in Catalonia

New York Coalition for Human Rights in CataloniaThe liberty of an oppressed nation can never depend on the form of government that dominates it; it depends solely and exclusively on the will of the people to achieve it.

–Lluis Companys i Jover (1882-1940)

Lluis Companys was the last democratically elected Catalan president to face (illegal) arrest and extradition by Spain. Companys was taken back to Barcelona in 1940, with assistance from Hitler and Mussolini, and killed upon Franco’s orders. Since the October 1st self-determination referendum in Catalunya, various Spanish politicians warned that the current democratically elected President of autonomous Catalunya, and now-leader of the Republic of Catalunya declared on October 27th, Carles Puigdemont, may meet the same fate when he comes back or is forced to come back from Brussels. Puigdemont traveled to the capital of Europe, with several Cabinet ministers to seek assistance defending the human rights of European citizens in Catalunya, when European and other world leaders did not come swiftly to Catalunya’s aid in the first days of the Spanish coup.

From graffiti in the streets of Barcelona, to signs at independentist and anti-austerity protests, locals from across the political spectrum display and explain the widespread understanding that was one of my first lessons as an anthropologist living and working in the region: “THIS IS NOT SPAIN.” For context, participants and research collaborators with whom I carry out fieldwork, including those who’ve become political comrades, taught me that there was a Catalunya before there was a Spain. At least as early as the 1100s, Catalunya existed as a nation on the Iberian Peninsula–an independent, autonomous, historically recognized Catalunya, later conquered by two European kingdoms that became Spain, more than three hundred years ago.

Barcelona street graffiti. Photo by author

Barcelona street graffiti. Photo by authorFor decades, a growing politically and culturally diverse grassroots movement in Catalunya has been struggling to reassert that freedom, drawing on an older, deep-seated cultural sense of autonomy but also inspired by the history of Catalan resistance to fascism and a commitment to inclusion and protection of migrants, defense of workers, and struggles for gender equality.

This background – Catalan history, culture, and past and current commitments – has not been covered by the mainstream press, in Spain, Europe, or the U.S. In fact most Spaniards have been prevented from ever learning it; it’s not taught in Spanish schools. As a result, many, including Leftists here and there, ignore the situation, react with skepticism, or downplay further Spanish repression since the recent October 1st referendum (when Spanish military police beat bloody almost 900 peaceful self-determination voters, and prevented or stole the votes of 770,000). Many appear to have been captured by the false narrative, promoted even by NPR, that Catalunya is trying to ‘leave Spain’ for narrow, exclusionary, nationalist reasons, or to keep wealth generated in Catalunya, solely for Catalans. The reality is that Catalan independentists have long organized in reaction to a history of lived experience with historical and financial occupation by Spain, political repression, and growing, reactionary right-wing, and creeping fascism – all coming from Spain’s government.

The starting point for this understanding of Catalan independentism, and of the current Spanish coup in Catalunya, have been my conversations over the past five years with Catalans, immigrants who’ve come to live in Catalunya and want to become part of the new Catalan Republic, and people who support Catalan independentism. They tell me they are asking for and demanding recognition of what Catalunya has already been –what was repressed for hundreds of years following the 1714 War of Succession, and especially under Franco, as well as the anti-fascist and communitarian organizing for which Catalunya has been known since its first Republic, under Companys’ leadership. The 1978 Spanish constitution recognized Catalan’s autonomy, but the Spanish central government prevented full implementation of the ensuing articles of autonomy. When the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) gained a sweeping majority in the early 2000s, they did so in part by promising the sizeable number of Catalan voters who supported them they would rectify this — but they did not fulfill that commitment in the seven years that followed. (Now, the Socialists have partnered with Spain’s far-right Partido Popular to oppose Catalan self-determination, and have failed to speak out against the Spanish violence of October 1st, or the coup.)

“People before banks” Anti-austerity march and rally, late 2012, Barcelona. Photo by author.

“People before banks” Anti-austerity march and rally, late 2012, Barcelona. Photo by author. Resistance to Austerity

Since 2012, and in the context of the economic crisis and resulting austerity accepted by Spain as a condition of Germany’s bail-out, in turn shoved upon Catalunya by Spain in an attempt to make Catalunya disproportionately pay for Spain’s financial rescue, the recent austerity measures, overlaid on the long history of autonomous identity and memory, fueled the groundswell of interest in full separation and increasing desire to demand recognition of the ways that Catalunya is different from Spain. A key driver of independentism, along with history, has been a recognition of the suffering caused under austerity, its effects on everyone in Catalunya, and a commitment to safeguard aspects of the Catalan nation that the Spanish government continually threatens to roll back: continuation of publicly funded healthcare including for unregistered migrants; guarantee of fully legal abortions; public multilingual education, and welcoming refugees including with subsidized housing.

An Inclusive Nationalism

All of these are characteristic of what makes Catalunya, and Catalan independentism, representative of what my colleague Nina Kammerer and I have termed an inclusive nationalism, as described by many Catalans, immigrants who’ve made Catalunya home, and by people who are recently arrived, but welcomed and included in the definition of what it is to be Catalan. They tell me, “This is what makes Catalunya different from Spain; this is what we are trying to protect, and build, by becoming fully independent.” Independentism is a rejection of far-right nationalism, a rejection of Spanish fascism, falangism, and neo-nazism. These movements have increased in Spain in recent years, as elsewhere in Europe, especially so around the Catalan self-determination referendum, and now in the ugly brew of the Spanish coup.

Catalan politicians and elected officials, including political prisoners imprisoned without bail for over a month for simply having listened to the people, have not been the ones leading the movement. They responded to calls by the people. The independentist movement has also become a more Left, more grassroots, and more open movement over time. The main body that has been guiding the independentist movement, the Assemblea Nacional de Catalunya, the national assembly, is a grassroots movement, with neighborhood-level representatives. Because of this, they have relationships with labor coalitions, with neighborhood associations, with civic organizations and cultural groups, women’s groups, immigrant organizations, and so on– which range widely in terms of how progressive and radical they are. It includes some of the more anarchist unions and even the farthest-left Catalan party often described as an anarchist party, the CUP, but also includes some labor coalitions and parties that, by U.S. leftist standards might seem progressive, but which are, in the Catalan, multi-party, pluralist, parliamentary context, far from the most progressive.

What I have seen in Catalunya, doing extended fieldwork there beginning in 2012, but first visiting and observing the independentist movement going back to 2009, is a collectivist understanding of historical lived experience that nevertheless makes space for the needs and experiences of newcomers. This understanding is reflected in the independentist movement which represents a wide diversity of people who are talking about what they want Catalunya to be, and for whom, and deciding together in this very communitarian way how they want to get there. The limits on the possibilities of what it can be, how radical and revolutionary it can be, are largely based on how violently Spain is responding, and will respond going forward — and how negligently and willfully the rest of the world is going to allow Spain to do as it likes.

Creativity and Collectivity

The limit is not on the creativity or the power of what Catalunya can do. In the few days before the referendum, parents, teachers, neighbors, and neighborhood self-defense committees organized to occupy and defend schools, civic centers, and other spaces to ensure not only that those who wanted to vote on self-determination could, but also that there would be neutral respite sites where people could seek medical care, food, rest, meet up with loved ones, and take their children if (when) things got ugly. People worked together to communicate securely, in real time, about where the Spanish military police tanks and trucks were advancing through towns across Catalunya, to redistribute protection guards to different polling places, and to get volunteer units of medics to care for those who’d been beaten. All the while, volunteers did art projects with the kids, Castellers (human tower builders) and dancers and musicians kept things lively, creative, festive, and inspired people’s bravery and fortitude, so that the movement would have the energy to keep going.

Castellers commemorate Catalan National Day, September 2017. Photo distributed by comrades in Barcelona.

Castellers commemorate Catalan National Day, September 2017. Photo distributed by comrades in Barcelona.For me as a scholar, and for the comrades I hear from on a near-constant basis, the looming threat to Catalunya’s creative spirit of resistance and organizing brings back memories of the Catalan revolution of the 1930s that preceded the Spanish Civil War, the war itself, and Franco’s long occupation of Catalunya after the war ostensibly ended. The First Catalan Republic had agrarian collectives, worker-owned cooperatives, legal abortion, legal divorce (long before the U.S.), and many other measures of greater equality, in comparison to other parts of Europe at that time. It was Franco that destroyed it, and the world let him. What will powerful nations now do about Spain’s coup in Catalunya? Watching NATO and EU members, the answer appears to be, very little. As Pau Casals, a world-famous Catalan cellist and composer said before the United Nations in the 1970s, upon receiving a Medal of Peace,

“Our only weapon is our solidarity and our people. . . . We need your help now more than ever…The struggle of the Catalans should also be the struggle of all. Help Catalunya.”

In the context of the current Spanish coup in Catalunya, young Catalans, including some who arrived in the region as refugee children from Srebrenica and other areas from which Catalunya welcomed thousands of displaced persons, re-enacted Casals’ full speech and asked that their video be sent around the world to call attention to the current repression.

Even in recent weeks, there are new developments in the post-referendum process: several of the Catalan government ministers-turned political prisoners arrested by Spain and held without bail were released in the first week of December; the arrest warrant for President Puigdemont has been dropped (at least for now – how long Brussels will host him remains to be seen); voters in Catalunya await news of the status of potential Parliamentary candidates whose parties should appear on the December 21st ballots but who, if they are still in jail without bail, may not be allowed to serve if elected; more than 60,000 people marched in Brussels on December 7th to demand the release of all political prisoners, to show support for President Puigdemont and his ministers, and to draw attention to the upcoming election.

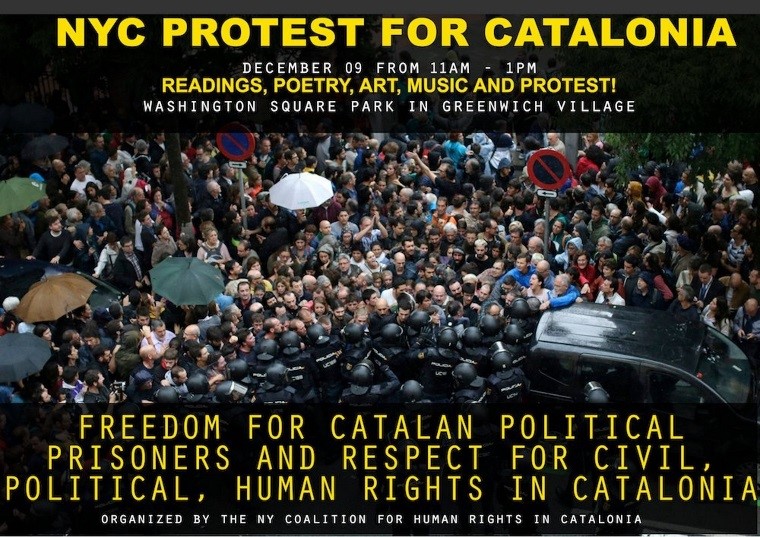

Last but not least, supporters of Catalan self-determination in the United States attended a snowy solidarity protest on December 9th in New York City.

Bayla Ostrach is an applied medical anthropologist and member of Solidarity