by Barry Sheppard

September 19, 2013

September marked two related anniversaries. The first was the collapse five years ago of Lehman Brothers, which came to symbolize the financial collapse, the subsequent Great Recession, and the anemic recovery. The second was the upsurge of the Occupy movement two years ago in response, which popularized the idea that the richest one percent are the enemy of the rest of us. This slogan has taken hold in mass consciousness, and is the enduring legacy of Occupy.

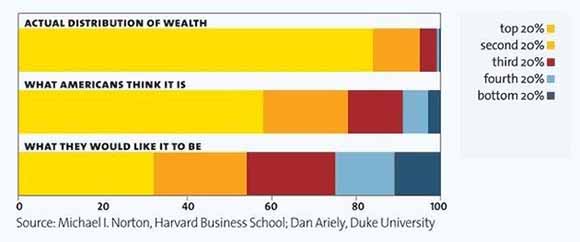

The divide between the wealth of the one percent and the rest of society is now at its highest since the government began collecting such statistics a century ago. The gap is even greater if we look at the one percent versus the working class, which makes up the majority of the 99 percent.

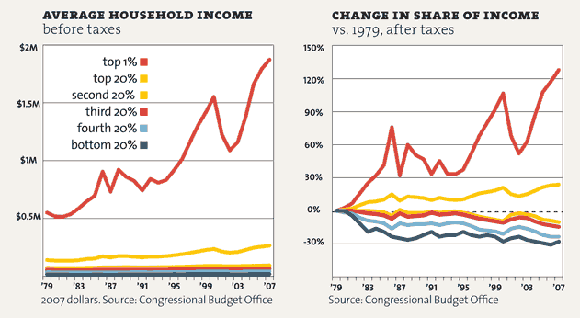

Changes in wealth by income percentile from 1979 to 2007 (the trend has only grown worse since ’07).

The wealth gap reached a peak in 1928, on the eve of the Great Depression. A comparable peak was reached in 2007, on the eve of the Great Recession. In the years since the end of the end of the recession in July 2009 (using official figures) the gap has grown. Up to 2012, the top one percent has captured 95 percent of the income gains in the recovery. The inequality is even evident among the one percent. Sixty percent of the income gains went to the top 0.1 percent.

The top 10 percent scooped up half the nation’s income in 2012. Meanwhile, the median wage keeps dropping. The median household income (which includes two-earner families) is 8.3 percent lower than in 2007. Since these figures include better protected, higher paid workers and management, the drop is greater for most workers. There are no countervailing forces to reverse these trends in the immediate future. We can expect the wealth gap will continue to grow in the years ahead.

Unlike in the present recovery, the wealth gap did not grow in the period of the 1930s after the crash. What accounts for the difference? In the 1930s there was the largest labor upsurge in U.S. history. Powerful industrial unions were formed and continued in the three decades after the Second World War, and won significant gains through struggle. Since then, labor has declined significantly, and continues to do so, to the point where only 6-7 percent of workers in the private sector are unionized. Public workers and their unions are weak and under attack. In this “recovery,” there simply isn’t the working class power to counter the rapaciousness of the ruling class, so the wealth gap continues to grow.

There has been a spate of articles in the press about the growing income gap, including in the New York Times and Financial Times, as well as in books by bourgeois economists. None put forth any serious proposals to alleviate the situation. Obama himself referred in a recent speech to the “one percent” and even to the “top 0.1 percent,” but beside bemoaning the fact and blaming the Republicans, he has not made any serious proposals either.

At the bottom, tens of millions are near or below the official poverty line. Since the 1970s, the bottom 20 percent has seen its wages fall. This has accelerated in the aftermath of the financial collapse. Census data show that nearly one in two Americans now is classified as low income or lives below the poverty line, itself set arbitrarily low (far lower than a true living wage). More than a third of African American and Latino children live in poverty as legally defined, often in hunger.

A new book by Sasha Abramsky, The Other American Way of Poverty: How the Other Half Still Lives, chronicles many of the poor’s stories across the country. His book updates Michael Harrington’s book of 50 years ago, The Other America. One story he tells sheds light on the fragile nature of the so-called safety net, that of Megan Roberts. This was even before the crash. She and her family had been on Medicaid, a medical insurance program for poorer workers.

When her husband got a raise of $1 an hour, that ironically made things worse. In her own words: “The dollar raise knocked us off [subsidized] housing. We went from $612 rent to $1,030 rent. It knocked us off food stamps, so we did not get any food assistance whatsoever. We had no Medicaid at that point because the dollar pay raise knocked us off that. It left us hanging. He [her husband] was only going to get private health insurance through his work. It would have taken effect January 1, 2006.

“But I got sick December 12, 2005. So we were left with this bill. We ended up having to – I believe it was April 16, 2006 – we filed for bankruptcy.” Megan’s story demonstrates the artificial nature of official definitions of poverty, and the fragility (often non-existence) of our social safety net.

A Modest Proposal the Financial Sharks Hate

The immediate cause of the financial collapse was the bursting of the housing bubble. With the collapse in employment and income in the Great Recession and its aftermath, millions of workers were unable to keep up with their mortgage payments on their homes, and the banks foreclosed on them. Some three million homes still are in danger of being seized through foreclosure.

In addition, there are millions of homes “under water.” That is, the price paid for them through mortgages during the bubble is higher than their market price now. Many people living in these homes continue to pay on their mortgages which are at the bubble price. They can’t pay off their mortgages by selling their homes because the selling price is much lower than what they owe.

The city of Richmond, CA came up with a plan to help such people stay in their homes and avoid foreclosure. Richmond would pay the holders of these mortgages (often “bundled” and sold by the original lenders) the fair market value of the homes. This would be the same amount the mortgage holders would receive if they foreclosed and sold the homes on the market. The city would then set new mortgages at the new fair market price, which would mean lower mortgage payments for the homeowners, and help save them from foreclosure.

Photo by Brant Ward, The Chronicle.

This would also help the city economically, both by putting more money into the hands of the homeowners, and by preserving home values from shrinking further. If the mortgage holders refused to sell, the city could use eminent domain to force the sale, at the market price. It should be noted that this whole modest proposal is based on the rules of capitalism and the market. Everything would be paid at current market prices. (The Obama administration could have done this on a national scale early on and averted much suffering, but did not.)

Big finance capital raised a storm of opposition to Richmond’s decision. Wells Fargo, Deutsche Bank, and Bank of New York Mellon filed suit against the city, saying the proposal violates protections against impairing private contracts. They also hired a public relations firm to launch a propaganda blitz aimed at all the residents of Richmond, charging that the proposal would lower property values (the opposite is true). Some opponents have charged “socialism.” As a result, the struggle has broken into the national media, and taken on national significance. If Richmond prevails, other cities might follow suit.

When the laws of the market benefit the rich, as they do almost all of the time, the rich are all for these rules. If workers can use market prices to make even modest gains, the rich are against it. Unfortunately, the rich almost always get their way.

Barry Sheppard is a member of Solidarity in the Bay Area. He has written a two-volume political biography about his time as a leading member of the Socialist Workers Party. He writes a weekly letter from the U.S. for the Australian Green Left Weekly and Socialist Alternative magazine, where this article also appears.