by Keith Mann

November 23, 2014

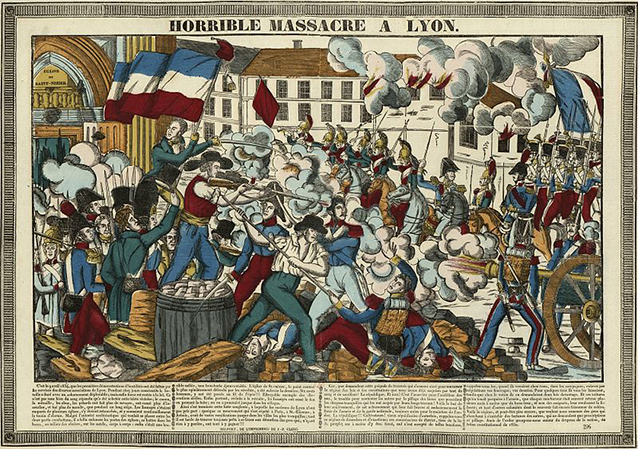

The young Karl Marx admired and drew inspiration from their tenacious struggle.1 French belle époque poet and cabaret entertainer Aristide Bruant (subject of a well-known poster by Toulouse Lautrec) immortalized them in his “C’est nous les canuts”, a song which has long been a staple of working class and left wing political gatherings in France.2 These were the weavers of the industrial city of Lyon, known in French as canuts (“can-oos”) in their masculine version, and canuttes (“can-oots”) in the feminine. In 1834, facing starvation during one of capitalism’s periodic crises, their misery exacerbated by a voracious local merchant capitalist class, they launched a furious struggle under the banner “Vivre Travaillant ou mourir en combatant”–live working or die fighting (there had been a previous revolt in 1831). For several days they fought pitched battles with local armed militia suffering numerous casualties followed by repressive judicial vindictiveness after the revolt was crushed.

These were not property-less proletarians in the strict sense. Rather, they were highly skilled craft workers who owned their own looms working under a system of domestic production carried out in their cramped apartments. In most cases, male weavers were aided by female family members who prepared the silk which was then mounted on spindles in preparation for the weaving. Merchant capitalists provided raw silk and design orders for various products. Dyers (tenturiers in French) were part of a later process that added color to the products. The class cleavages, and struggles, sprung from the amount of pay (the tariff) paid by the merchants (called fabricants in French although they fabricated nothing but exploitation) to the canuts and canuttes. In times of boom the canuts and canuttes enjoyed a relatively high standard of living which resulted in a high rate of literacy and radical craft pride. When demand declined, so did work orders and the tariff rate.

This system existed since the late Middle Ages and early modern period when Lyon became the cross roads of a precocious international trade in silk products. Evidence of the prosperity of the merchants can still be seen today in Lyon’s old town in the well persevered, tastefully designed residences the merchants built during the 16th century, (this was the period of the French renaissance for which architecture was paramount). The dominance of this nascent bourgeoisie with their refined tastes, at a time when parasitic landed feudal lords ruled over French and European society, gave a certain modernity and sophistication to Lyon’s social climate. The 1834 crisis and revolt it sparked was not the first time the city’s social tranquility was disturbed. Economic crises in 1744 and 1786 had also led to acute social tensions and revolt.

The silk weavers and dyers were also at the forefront of other political and class struggles. The city hall in the city’s fourth district or arrondisement bears a plaque commemorating the uprisings of 1848, in which the weavers play a prominent role.3 The Paris commune of 1871 found one of its rare provincial echoes in Lyon when a revolutionary government took power before being overthrown after several days.

From the late nineteenth century through the 1920s the traditional labor system of silk weaving production steadily gave way to more modern forms of industrial production as changing fashion styles, mechanization, the invention of artificial material like rayon, and increased availability of capital led to mechanized factory production. By the 1930s silk production was largely carried out in medium and large sized factories employing a mostly female semiskilled labor force. The skilled dyers too were replaced by mechanized semi-skilled factory arrangements. As union density increased in the 1930s many Lyonnais textile workers joined these unions, often organized by the French Communist Party.

The 1934 US Textile Strike

A hundred years following the 1834 silk worker revolt in Lyon, 400,000 semiskilled and largely white workers4 on the US east coast stretching from Alabama to Maine launched a desperate struggle in the depths of the depression for union recognition, a living wage (many suffered near starvation in spite of working 55 hours a week in the mills), dignity (foremen were particularly harsh and sexual harassment against women workers was widespread), and most of all against speed-up referred to in the southern mills as the “stretch out.”5 As was the case in Lyon a hundred years earlier, the industry suffered an acute crisis brought on by the contradictions of the capitalist system: in this case overproduction which led to falling prices for cotton and other textile products.

Striking textile workers march through Gastonia, NC.

The revolt was inspired not only by the horrendous conditions but by the worker’s interpretation of the largely toothless National Industrial Relations Act (NIRA), New Deal legislation that authorized unions and collective bargaining.6 “Flying squadrons” of motorized workers in their beat up jalopies sought to erect and reinforce picket lines and prevent scabs from entering the mills. This was class struggle in its most naked and brutal form. The flying squadrons and other tactics attested to the tremendous creativity of the strikers. The repression was brutal. Local police, state militia, and vigilantes in the pay of the mill bosses did not hesitate to use deadly force against the strikes. Scores were wounded and several killed. Many were shot in the back as they fled the police riots.

All of this was carried out with very little help from national AFL-affiliated unions. After 22 days, the strike was ended, sold out by union bureaucrats with little knowledge of the mill workers’ plight, particularly those in the South. The workers returned to the mills with nothing but vague promises that their grievances would be considered and that workers would be re-hired without discrimination regarding their participation in the strike. Those promises were honored in the breach. Conditions in the mills remained horrendous, wages low, and over 75,000 workers were blacklisted, many forced back into the impoverished upcountry towns and villages from whence they had come. Decades later the bitterness and fear engendered by the striker remained, contributing in no small part to the weak implantation of unions in the South.7

Both the 1834 silk worker and 1934 textile revolts were defeats, but both reflected the determination of working people to struggle against seemingly insurmountable odds when they simply could no longer accept starvation wages and intolerable working conditions. Their struggles are an inspiring part of the history of working people’s determination to defend themselves. Today, as low wage workers at companies like Wal-Mart and fast food outlets move toward increasing confrontation with their employers, they knowingly or unknowingly pick up the thread of the heroic struggles of Lyon’s silk workers and the US textile workers in the dirty mill towns of the 1930s. And when they do, their wage masters can expect the same sort of fierce resistance of their counterparts in the past. But this time, hopefully, the workers can expect aid and support from other workers and engaged community forces.

Keith Mann is a member of Milwaukee Solidarity, and author of Forging Political Identity: Silk and Metal Workers in Lyon, France, 1900-1939 (Berghahn Books, 2010).

Footnotes

- Mentioned in his article “Critical notes on ‘The King of Prussia and Social Reform by a Prussian’ published in volume 63 of the German language newspaper Vorwarts, on August 7, 1844. In the same article, Marx also rendered homage to the textile weaver’s revolt in the German province of Silesia in June of 1844.

- The first few stanzas of the song recount the misery of the canuts/canuttes. But the last stanza is more uplifting. Here is a rough translation: ‘But our reign will commence when yours (the merchants’) ends. We’re weaving the funeral shroud of the old world for we already hear the cry of the coming revolt. We are canuts and we will no longer live in misery.”

- This is the Croix Rousse neighborhood to where many canuts and canuttes moved from their cramped apartments in the old town following the invention of the Jacquard loom in the early nineteenth century.

- Blacks constituted perhaps 2% of the work force and were relegated to the most poorly paid, ancillary jobs such as sweepers and haulers.

- In spite of the huge numbers of workers involved, this strike is far less known than the more celebrated strikes in Minneapolis, Toledo, and San Francisco which also took place in 1934. To learn more about the textile strike see Janet Irons’ Testing the New Deal: The General Textile Strike of 1934 in the American South (University of Illinois Press. 2000).

- The 1935 National Labor Relations Act or NLRA, which is still law today, offered a slightly more enforceable version of the NIRA.

- See this moving trailer to a recent documentary on the strike.