Promise Li interviews To Chi-kuen of Borderless Movement

Posted November 16, 2020

Interviewer’s note: Hong Kong’s protest movement has seen a major setback with the introduction of the National Security Laws in July. In this atmosphere, continuing to archive, analyze, and humanize the political choices protestors made is no retreat. Rather, it’s a necessary part of advancing the city’s ongoing fight for democracy and self-determination, while making sense of its contradictions. In January of this year, I had the privilege of sitting down with my friend and comrade, To Chi-kuen (杜志權), for an evocative discussion documenting his journey through Hong Kong’s social movements over the last decade or so.

Kuen’s experiences complicate a linear perspective of Hong Kong’s political opposition and its histories, and shines a light on under-reported aspects of political organizing in the city—some of which are obscure even to many of his fellow Hongkongers. Kuen knows well that there are neither easy victories nor total defeats. From organizing his co-workers as a rank-and-file truck driver to serving as a community de-escalator in the protests last year, Kuen’s story takes us from Hong Kong’s little-known workers’ organizing and left-wing circles to the frontlines of an international geopolitical struggle. Through his political biography, Kuen reminds us of what he sees as the core values of being a left-wing organizer and political activist.

This interview was translated by the interviewer from Cantonese into English. The text below has been condensed and edited for clarity. It appeared on the Lauson website on October 17, 2020 here.

‘It was natural for us to look out for each other and defend one another’s interests in our workplace’

Promise Li: Hong Kong burst into the international spotlight with the 2014 Umbrella Movement and the 2019 anti-extradition bill protests. But your experience in community organizing goes back earlier before these movements. Can you tell us more about how you became politicized and what your earliest political experiences were?

To Chi-kuen: To be honest, my personal interest in politics was not really about helping others at first; it was about self-protection/self-interest (自保/自利). I started by participating more in my apartment complex’s tenant association, encouraged by my mother. It was the first time I wasn’t just trying to work hard for myself and family, but was devoting extra time to participate in something beyond myself. I thought it was a good way to advocate for my own interests as a tenant at the time while being able to help others.

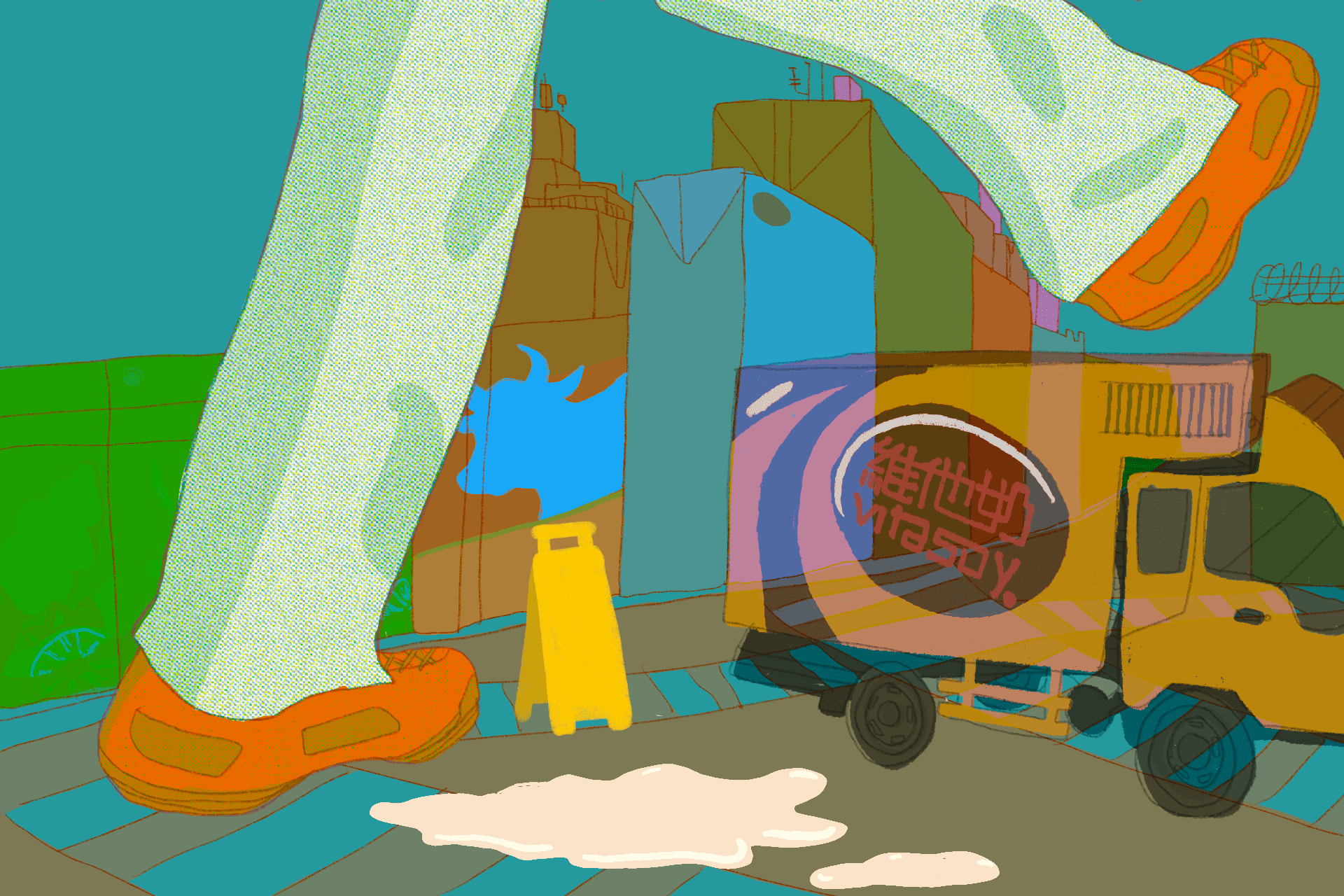

Then, I became more politically active in my workplace. In the early 2000s I started working for Vitasoy—a very large corporation. (1) I was already working as a driver for small transport companies since I was an older teenager but this was my first time working for a big corporation. In my old jobs, you can see the boss every day and bring any grievances directly to him, but at Vitasoy, you might not meet the higher-ups during your whole time in the company. For us, the work is pretty straightforward: we deliver the goods to the preset customers, from vending machines to markets, and we get our paychecks. For the bosses and management, the main task is looking for ways to make more money—a lot of times this is done by cutting our wages. So there’s a contradiction in the workplace. They employ a lot of rhetoric to remind us of our precarity, to make us stay and work, saying they don’t need us and that there are other workers waiting to be hired. So we Vitasoy workers tend to begrudgingly accept our positions.

But more and more people eventually started questioning why the management persists in cutting our wages while the company’s profits continue to increase. We couldn’t talk to the bosses about these grievances, and I realized that we couldn’t fight this alone. We needed to resist together, collectively. I guess that’s when I first started thinking about what you can call “organizing” now. Even then it wasn’t out of any political principle, but more about standing up for myself and some of my coworkers and friends since a few of us became close after years of working with each other. I see my colleagues more than my family, and I entered Vitasoy in my early 20s, so it was easy to develop close ties with people. It was natural for us to look out for each other and defend one another’s interests in our workplace. So it wasn’t about anything like pushing for systemic political transformation at first, where I’d be helping to fight for people I don’t know as well.

In addition, Hong Kong labor protections are almost non-existent so it was dangerous to do shop floor organizing, and one could be easily fired. But our managers kept making pay adjustments to cut our wages, saying things like they miscalculated and we are actually making more than the market rate, and etc. In 2003, SARS happened and their excuse for cutting wages was that everyone needed to share this burden together to weather this crisis as a “family.” Indeed, consumer demand went sharply down, since you didn’t have to drink Vitasoy as much—it’s non-essential. We were already making less since our pay depends on how many orders we can deliver.

They said that they’re cutting our pay because they don’t want to fire people. This sounds kind of reasonable at the time to us with the sharp drop in deliveries, but remember: SARS didn’t last that long, and workers started questioning why our wages weren’t returning to normal even after the epidemic subsided and business went back to normal. We can see the company profits and they’re making a lot again—but without raising our pay. Since then there were a lot more internal tensions, and more people were skeptical of whatever the management said. When they announced another “pay adjustment,” we would calculate it on our own; sure enough, we’d always discover that these “adjustments” weren’t fair.

Ten years into my time in Vitasoy, I became more and more well-known on the job for helping to bring my friends’ grievances to management. Some would ask me to help communicate specific frustrations to their managers, either because they weren’t ready to confront them on their own or they didn’t know how to. Again, I didn’t see this as activism or organizing yet: it was helping out friends. The management would ask why I’m sticking my nose in other departments’ businesses and that’s what I’d say.

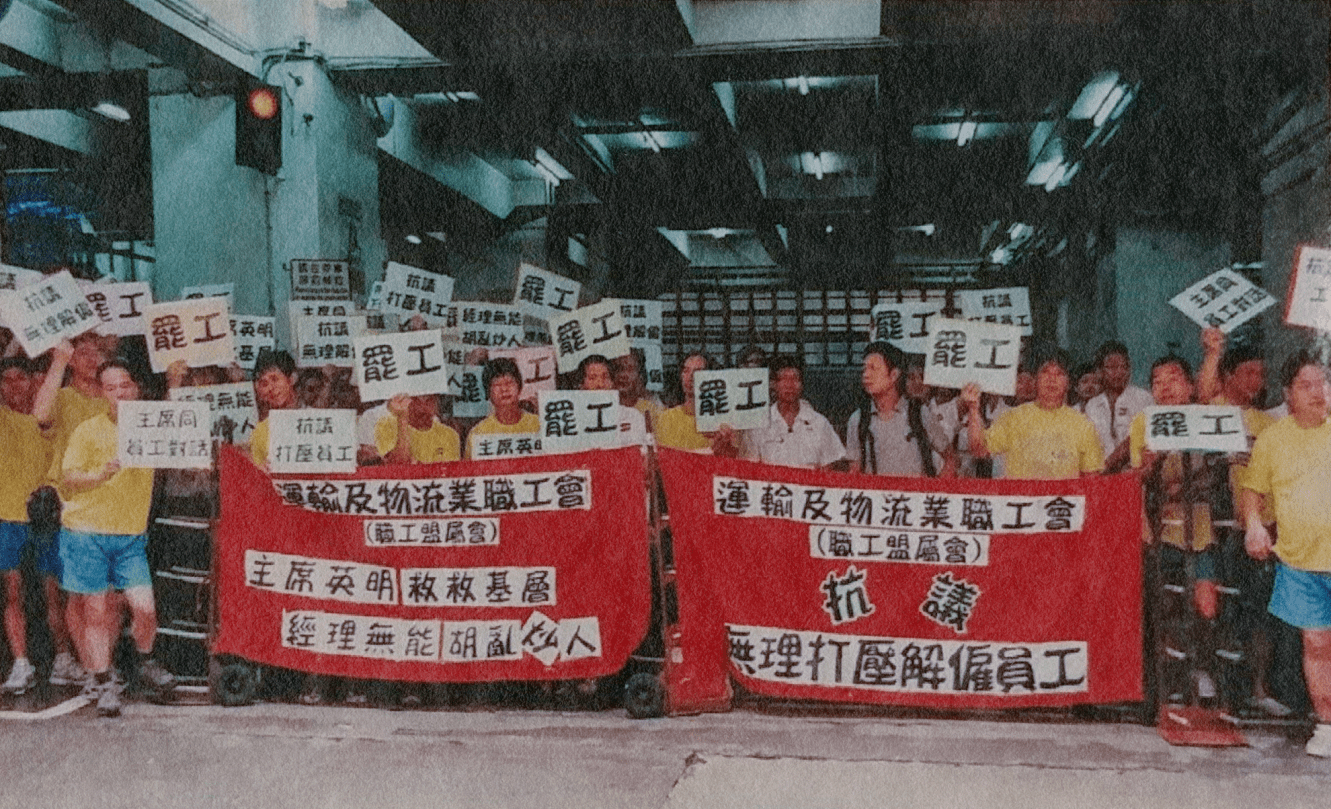

It wasn’t until getting fired in 2008 when I really organized with my colleagues. By that point, people were sick of another wage cut and things reached a breaking point. I started organizing other workers to not take the wage cut and collectively negotiate with management. They quickly realized that we were seriously organizing against them and decided to pluck it at the root. One morning, they silently fired me and sent me home without explanation. Even though the company was big, word spread quickly on the shop floor and on the same day, my closest friends at work contacted me and said we needed to organize and strike. They said at the time, if they can fire you, they’d fire others who try to speak up in the future too. We didn’t have a union at the time, we were just figuring things out ourselves. My friends confirmed that as long as I’m willing to come back to help lead this action, other workers will join. But at the time, we didn’t really know how to organize a strike, we just had the heart to fight the boss, so we looked for help.

At the time, word on the streets and what we saw on TV often was that the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU) was the group usually helping out with strikes and workers’ issues, so I reached out to them. (2) There were old colleagues at the time who asked me why didn’t I try the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU), and even then, I had known and heard enough from other workers to know that HKFTU doesn’t have workers’ interests in mind. Despite their radical past, they have been focused more on getting workers and bosses to come to a quick agreement behind the scenes, and helping bosses make sure you don’t organize in recent years.

So we went with HKCTU, which taught us the basics of how to strike, and how to tell the difference between ‘unreasonable termination’ and ‘unlawful/wrongful termination’. Apparently, they said that Hong Kong law at least guarantees that firing a worker for joining a union counts as unlawful. So we all joined the union before we launched the strike. It ended up being successful, and most of the people in logistics stood side by side to oppose the boss. Honestly, at that point we weren’t totally sure about HKCTU’s assurance that we can’t be legally fired after joining a union.

Afterwards, the union really wanted me to return to work to keep organizing, but I really couldn’t stay in that environment. When I first joined, at least some of the managers began as workers like us on the shop floor and there was more sympathy and room for negotiation. But by the time I was fired, college-graduated bureaucrats, who are trained to strengthen the management’s power against workers, had already filled the management’s ranks. I saw that despite our victory, this trend wasn’t going to change and I decided to take my chances and use my severance pay to buy my own truck to do freelance deliveries for a while with a friend.

‘Helping others in politics doesn’t have to be separate from helping myself’

PL: Workers’ organizing in Hong Kong is not usually something popularly discussed but for you, your experience in rank-and-file workers’ organizing directly leads into your participation in the city’s recent major social movements. Can you tell us more about how one led to the other for you?

TCK: HKCTU still continued to keep in touch with me, and eventually persuaded me to join its ranks to talk to more people about unionism and grassroots solidarity. This was the first time I started really connecting local struggles to larger dynamics of political oppression in the city. So I helped out on staff in HKCTU for a while, organizing small-scale protests, and doing some lobbying work for better labor policies. We didn’t have minimum wage at the time yet, for example, and we organized to bring that to the Legislative Council. This was when I really learned that we need collective power to protect oneself and others’ interests. I left HKCTU in a few years, after the union’s General Secretary Lee Cheuk-yan approached me to run for district council elections to energize working-class voters. (3) I quickly realized that the electoral path was not for me; one reason was that, because of my low education, and my poor reading and writing skills created real limitations for a role like that. So I dropped the prospect and took a break from organizing to focus on work.

In 2013, Benny Tai and others began talking about Occupy Central, and I began getting more involved again—this time in a larger social movement. I began participating in the ‘Deliberation Days’ or ‘D-Days’ conversations, where members of the public were invited to discuss Hong Kong’s political future together, not just political leaders. Around that point, I had less financial burden: I had just finished paying off my apartment after decades and my son had started working. So I made a decision with my family to quit my full-time job and devote more time and energy to the burgeoning social movement.

During this period, I met new friends in the movement and this was when I really first learned about left-wing ideas more rigorously. I met people like Au Loong-yu, who taught me a lot, especially the principle that helping others in politics doesn’t have to be separate from helping myself. This echoed something I said to a reporter in 2008 after the Vitasoy strike. She asked me how I viewed the result of the strike, which saw higher wages for my co-workers but me still getting fired. I said that we can’t just look at immediate gains and need to look at larger, social, or industry-wide impacts of actions like these. I still worked as a truck driver afterward in the same industry, and since Vitasoy is a large corporation in a small city, our victory was able to set a new industry-wide wage standard. So even though I got fired, by helping other workers raise their wages, I end up indirectly improving conditions for myself too, still working as a truck driver. The important thing is that you never know when engaging in collective organizing would actually end up materially benefiting your own conditions too.

‘I still don’t know what we could’ve done differently then’: Reflections on Umbrella

PL: The Umbrella Movement started right around the years Benny Tai’s initiatives began taking off in public discourse. What was your participation like during Umbrella, and what are your observations about that movement’s political direction and kind of organization? Lastly, how do you interpret Umbrella’s failure and the years since, leading up to the protests last year?

TCK: So during the Umbrella Movement, I had more time to get involved but struggled with figuring out what the best role is for me in the beginning. I heeded the call to occupy Central, risking arrest to engage in civil disobedience. Only, of course, at that time, no one was arrested indiscriminately like they are now. I wasn’t involved in political leadership but I attended the occupation a lot. I was naturally pretty good at de-escalating conflicts, especially when things often got tense between protestors on the ground, and eventually I was looped in to help out by some self-organized groups to serve as security and de-escalator in the occupying locations. I felt like the role was a good way for me to contribute to the action, though not all the occupation sites welcomed such a role.

At the time, the three main points of occupation—Admiralty, Causeway Bay, and Mong Kok—had very different vibes. Admiralty recognized the leadership of some prominent liberal political figures like Tai, though the situation got pretty muddy toward the end. Mong Kok had more organizations fighting for power and the dynamic was much more combative and territorial between the protestors. Though there was a pretty helpful democratic platform to feature different voices during the occupations, whoever had the loudest voice or most supporters got more of a platform in Mong Kok. I think democracy should entail respectful and accountable processes for dialogue and debate, and this was something eroding from the start.

I really felt the power of state repression for the first time in 2014, when it felt like all the resources and energy spent on the occupation weren’t amounting to many positive actions from the government, which continued to operate with impunity. The younger folks were getting agitated by the traditional, pan-democratic leaders’ incessant and ineffectual meetings, and wanted to escalate. I can already sense the public opinion shifting rapidly against us as the government was content to let the occupation drag on and let us fizzle out. I asked the pan-democratic leaders how we can continue the momentum and maybe rework the movement so it can be sustained without making it feel like we are retreating or giving up. No one gave an adequate response at the time, and to be honest, I still don’t know what we could’ve done differently then. Of course, the movement faded and Hong Kong social activism ebbed once again.

‘People think they don’t have power and abstain from participating in the few venues they have to influence how things around them are run’

TCK: People faulted traditional pan-democratic organizations for the loss, and there was a lot of in-fighting afterward in Hong Kong political circles. One positive thing for me at least during the time after Umbrella is that there was more time to think, self-educate, and process larger political questions. I read and learned more about what it means to be a part of a social movement, and how to think of Hong Kong’s struggles alongside other oppressive regimes globally. I learned and read a lot in these years and participated in smaller-scale social activism, building organizations like Voters Rising (選民起義) and Borderless Movement (無國界社運).

Voters Rising was formed to stimulate people to pay attention to electoral politics, not just to center on personalities but to talk about what it means to push for concrete ideological platforms. And if you aren’t convinced by certain candidates’ platforms, how can you still engage in community activism to change things? I also met Eddie Chu Hoi-dick (朱凱廸) in 2016 and helped him with his electoral campaign, and deepened my engagement with people in the movement. (4) Borderless is more explicitly left-wing and became a small hub for political education and discussion that continues to this day, and also served as an online publication to stimulate left ideas in political discourse.

I did stuff like that all the way up to the eve of the anti-extradition bill protests in 2018/early 2019. Some Borderless friends and I started Community Self-Organizing (自己社區自己搞), where we’d set up street stands to promote popular education about political theory. Borderless is mainly a publication and discussion space to bring left-wing political ideas and history to a Hong Kong audience. I’m more of a listener than a writer, and I’d try to understand as much as I can and rework these theories in accessible ways for a broader audience.

Many Hongkongers, largely because of the colonial educational system, just think the government is immutable, and that people have no real power and we should just adapt to new laws that are given to us. We would try to talk to people on the streets about how governments are products of history and can be transformed, and how people can build power and hold them accountable to meet our needs. We noticed that people have a lot of grievances, but have been so engrained in thinking that they have no political power and cannot influence policy. We also ended up producing three short pamphlets, analyzing distinct sectors that we thought would be relevant to everyday people to encourage them to organize and build power where they’re at. One pamphlet addressed education, and how both the colonial and CCP regimes reinforced an education system that prioritizes training people as laborers for the market rather than actually developing people’s interests and capacity to think independently.

Another Borderless member who studies labor history in his free time wrote one on labor rights, and I wrote one drawing on my experience participating in tenant associations. These associations are really a microcosm of Hong Kong society; people think they don’t have power and abstain from participating in the few venues they have to influence how things around them are run. We pay fees to these housing associations, so shouldn’t we deserve to have say over the conditions we live in? So by focusing our discussions on education, housing, and labor, we want to show how people can be empowered to change things around them through engaging in very immediate parts of their lives. But this project was difficult to sustain, and while people were interested in listening to us, most ended up just telling us to keep up the work but say they were too busy. And shortly after we took a break, the anti-extradition bill mobilizations began.

New foundations and difficulties in the 2019 movement

PL: What is your role and perspective on last year’s protests, and how was it similar or different from your experience of Umbrella?

TCK: One important thing to note is that the groundwork for the movement actually already started back around February or March of last year. Though some of these mobilizations were much smaller in scale and have barely caught the public eye yet, we see already what I think is one of the most important and under-discussed elements that kickstarted the larger movement: the role of student organizing. After 2014, many of the student groups imploded in various ways. The Hong Kong Student Union, which played a pivotal role during Umbrella, saw internal splits and were left with only four associated schools at one point.

Most social movement activism between then and the anti-extradition bill protests was mainly held up by a lot of older folks—other long-time activists. May was the breaking point last year but that energy would not have been possible without the initial rise of secondary school students self-organizing “anti-extradition bill concern groups” within their campuses. The youth became stimulated en masse again for the first time in years, and over a thousand local or campus-specific concern groups surfaced before June. This eventually sparked similar concern groups self-organized by parents, by region, online, and even by certain apartment complexes’ tenant associations. In other words, the massive June 9th march was neither a sudden nor isolated affair.

Whether this movement is successful or not, the ray of light for me is that my fellow protestors showed me that change is possible.

So these different groups began from discontent over the specific bill and quickly tackled larger issues about Hong Kong’s political future. This was a huge difference from the years before 2019 and before the Umbrella Movement. As a leftist, I thought it was an important victory already on a basic level that everyday people were energized to collectively determine and work out their own political future.

As I’ve said, I think my values are pretty simple at the end of the day: the ruling class suppresses and disempowers oppressed and marginalized people at the bottom. Capitalist forces—from the government to real estate moguls—disenfranchise us, and we the exploited must rise up to defend our rights. And this movement showed me that people are learning to organize to take back these things. History and the current situation suggest that we might probably fail this time around again, but we have this record for the future: that Hongkongers tried their best to stand up against their oppressors and we have something to contribute to the history of mass movements, and for our own future movements. Whether this is successful or not, the ray of light for me is that my fellow protestors showed me that change is possible.

This is not to say the situation isn’t grim. Despite loud gestures from world leaders, international support has not been that successful in stopping Beijing’s repression. The US’ HKHRDA last year, for example, not only does not accomplish much for the Hong Kong people, but if you read the contents of the bill, it’s clear that it’s all about the US’ own self-interest. The sanctions, for example, benefit no one but the US, and is clearly using Hong Kong for its own purposes.

International solidarity from below has not been built as strongly yet, and it continues to be more difficult than ever to stay connected with the resistance and dissent in the Mainland, let alone support them. Cross-border solidarity is obviously important, but how we do that effectively and strategically remains to be seen and continues to be debated by the left. Beijing is keen to not totally eradicate its opposition, but only to disarm or co-opt it and keep it within its grasp. The movement’s rejection of leadership is one tactic to bypass this problem: it’s hard for Beijing to know who to target if everything is decentralized.

This time, the movement has changed so fast, and the political situation can look radically different from one day to the next with no clear direction. This is pretty different from 2014, where there were much more clear leadership, proposed schedules, and so on. The protestors and the government were circling each other like chess pieces, and the government had no clear strategy either.

I found myself taking on a similar role as the one I took up during Umbrella though in a very different context. I stayed on the frontlines with other friends, from social workers to local politicians, to help as a community de-escalator to prevent the police from brutalizing the protestors. This was effective at first, when the police were sensitive to the media and cameras. I would find myself on the frontlines urging folks to calm down, and tried to encourage the police to stay rational and not unilaterally escalate and attack the protestors. The main point is to prevent violence as much as possible, if not at least buying time for other protestors around me so they can leave safely.

Of course, my role gradually became more ineffective as the police grew completely irrational, and the protestors on the frontlines were also losing patience with each confrontation. I’ve seen way too many protestors get violently beat up. One thing the media doesn’t report as much is that most of these “confrontations” are really just protestors trying not to get beaten up by the police while delaying retreat as long as possible. There really is no way for protestors, with scrappy DIY gear, to actually take an offensive against the cops in riot armor.

One of the few times I actually witnessed the cops being forced to retreat by the protestors was in Kwun Tong, when the police cornered the protestors so much that they were forced to fight back head-on. Eventually, I tried to draw from my years of experience in the movement to engage with other protestors on the ground, analyzing tactics and strategies with and in support of them. For example, I tried pointing out some of the frontliners’ increasingly sacrificial or martyr-like attitudes to police confrontations, and asking them whether this is effective for the movement in the long run.

Is losing that many comrades worth it? How can we continue to stay tactically flexible, and keep thinking about the movement’s substance and direction un-dogmatically? Molotov cocktails may be visually powerful, but does that actually deliver long-term, substantial blows to state violence? As the months dragged on, the police suffered minimal injuries, whereas we are losing protestors to arrests and injuries by the thousands. Some protestors call me “left plastic” (左膠) (5) for being averse to the violence, but I will continue to show up to support and be there with them as the movement continues to work out its future.

Notes

- Vitasoy is a beverage company whose products have been a cultural touchstone in Hong Kong for decades, found in most vending machines and grocery stores in the city.

back to text - HKFTU and HKCTU are the two main labor coalitions in Hong Kong, representing most of the city’s trade unions. The former has a long history of workers’ organizing, especially during the 1967 riots, but since Beijing’s turn to market reform and the 1997 Handover, it has consistently negotiated against workers, barring legislation to call for the right to collective bargaining, and holds an unchallenged hegemony in the Legislative Council’s Labour functional constituency. The latter is pro-opposition, which grew from a mix of independent unions, church-affiliated workers’ groups, and other grassroots organizations into a key force in the opposition camp post-Handover. Its ties to some foreign funding, bureaucratic internal structure, and historical lack of major organizing successes have invited criticisms.

back to text - Lee Cheuk-yan is a long-time political leader in the city’s political opposition and one of its most visible labor activists. He also co-founded the Labour Party and has served for years in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council. Most recently, he was one of a number of high-profile political figures arrested earlier this year for participation in the anti-extradition bill protests in 2019.

back to text - Eddie Chu is a progressive activist and politician who led a number of grassroots, anti-displacement campaigns through community groups like Land Justice League, and played a prominent role in the past year’s anti-extradition bill protests on the streets and in his capacity as a current Legislative Council member.

back to text - A derogatory Cantonese catchphrase for people who are left ideologically and unstrategic practically. It first became popular as a derogatory phrase against certain protestors who object to any form of escalation and radical action.

back to text