Posted April 29, 2008

Order your copy of Hell one Wheels today!

| One copy – $2 | |

| Five copies – $5 | |

| Fifteen copies – $10 |

Bigger bulk orders are also $.75 per copy. Inquire by emailing us!

The review below is from The Chief-Leader, New York City’s Civil Service weekly newspaper.

Rise and Fall of New Directions: TWU Got Fooled Again

By ARI PAUL

How did a reformist opposition caucus struggle for a decade and a half in one of the city’s most rambunctious unions, only to die a year after it came to power? This is the question Transport Workers Union Local 100 officer and New Directions co-founder Steve Downs attempts to answer in “Hell on Wheels,” his just-published book.

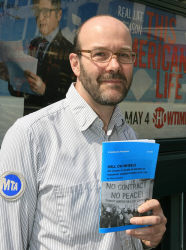

BEFORE THE WHEELS CAME OFF: Steve Downs holds a copy of his book, ‘Hell on Wheels,’ about the dissident group New Directions that accomplished a changing of the guard in Transport Workers Union Local 100’s leadership only to find itself marginalized by Roger Toussaint after it helped him win the union presidency.

The Chief-Leader/ Adrienne Haywood-James

In the process of describing its history, Mr. Downs also argues that current Local 100 president Roger Toussaint, who broke with New Directions shortly after he was first elected in 2000, was always more interested in top-down leadership than building the union from the grass roots up.

Like many of his comrades in Solidarity, a Detroit-based socialist organization, Mr. Downs ventured into the mainstream workforce two decades ago in order to reform an influential union. He obtained work as a Train Operator at what was then called the Transit Authority to organize members from the ground up.

Union Too Cozy?

The Local 100 leadership under then-President Sonny Hall had been conciliatory towards management in some members’ estimation, Mr. Downs begins.

Members were disenfranchised from the decision-making process and were left in the dark about the direction of the union, he writes, saying that it didn’t even have a newsletter. Fellow Train Operator Tim Schermerhorn collaborated with Mr. Downs and New Directions, which had no relation to the United Automobile Workers dissident movement of the same name, was born.

Hell on Wheels

The group started by holding meetings for members and the publishing a newsletter called Hell on Wheels.

New Directions members became vocal against the givebacks in contracts with the TA. Mr. Downs explains that in 1992, Mr. Hall had negotiated a contract with wage and benefit cuts for new hires, because as the union president explained, “Downsizing is going to come. We have to get as much as we can for the people who are left.”

Mr. Schermerhorn became the New Directions candidate for president, who hoped to not only democratize the union but to form a leadership that would more militantly fight management for better contracts and conditions. The next two Local 100 presidents, Damaso Seda and Willie James, were part of the so-called old guard, whose contract settlements continued to anger New Directions members. Mr. Downs explains that after the authority tried to lay off 2,000 Cleaners, Mr. James secured a pledge from the TA to keep a “minimum number of cleaners on payroll” in exchange for his allowing “WEP workers (welfare recipients forced to work for their welfare check) to clean trains, stations and buses.”

Toussaint Hops Aboard

It was during the James years that as New Directions grew in numbers, it saw the addition of two prominent members. Track Division Chairman Toussaint, a maverick who had learned the art of militant protesting during the civil unrest in his home country of Trinidad and Tobago, joined in 1994. Three years later, Stations Division chairwoman and former James loyalist Darlyne Lawson came in with her followers.

In 1999, Mr. Downs writes, the New Directions executive board members were able to win a victory for union democracy by forcing the union to hold a general membership meeting in December, which he calls the first of its kind in “a generation.”

And he shows that in the same year, two factions in New Directions emerged, one with himself and Mr. Schermerhorn honing the group’s ability to organize on-the-job actions against management, while Mr. Toussaint believed it should focus on influencing union contract demands.

Roger Not the Radical?

POLITICAL PRAGMATIST: Although much of the media has long viewed Transport Workers Union Local 100 President Roger Toussaint as a radical, former ally Steve Downs in his new book says Mr. Toussaint faulted the dissident group New Directions as so radical ‘that it scared people away,’ and once in office used union staff jobs to buy the loyalty of fellow board members.

Despite Mr. Toussaint’s reputation as a radical, when he challenged Mr. Schermerhorn to run for president as the New Directions candidate in the 2000 election, Mr. Downs writes that Mr. Toussaint already showed signs of watering down the group’s rhetoric. According to the author, in the contract fight in 1999, it was Mr. Schermerhorn and not Mr. Toussaint who called for a strike authorization in defiance of then-Mayor Giuliani’s court injunction against the union either going on strike or discussing a work stoppage.

“In his bid for the nomination, Toussaint argued that ND was perceived by the membership as too radical and that it scared people away,” he writes. “Instead of telling the members how much they would have to do and risk after electing ND, he wanted to pitch the campaign in terms of choosing a new leadership to clean up and rebuild the union.”

Mr. Schermerhorn did not help his cause when he made the public-relations blunder of stating, first at the Brecht Forum and then in a New York Times interview just before the 1999 contract expired, that he would relish a strike near Christmas to deprive businesses of their “orgy of profit-taking.”

‘Tim Wasn’t Up to It’

Former New Directions activist Ainsley Stewart insisted that Mr. Toussaint was the more-charismatic leader and thus able to become the new candidate for the caucus.

“It was a simple thing,” he said last week. “Tim had run on two occasions and he didn’t make it to the top, and he established himself as more or less an unviable candidate, a candidate who was too weak for the task. This Toussaint guy came along, a guy who barked loud and gave you the impression that he could bite, and everyone went towards him.”

In addition to popularizing the phrase “plantation justice,” in reference to his termination from NYC Transit, Mr. Toussaint was known for battling the Local 100 administration after he and several other officers were barred from contract negotiations, a violation of the union’s bylaws.

In the summer of 2000, New Directions members chose Mr. Toussaint as their candidate over Mssrs. Schermerhorn and Downs. Mr. Toussaint was able to win and bring New Directions to power that December, after the old-guard ticket split between Mr. James and another veteran Local 100 officer, Eddie Melendez.

Upon his rise to power, Mr. Toussaint and his staffers “stayed away [from New Directions] and the group ceased functioning within a year,” Mr. Downs writes.

‘A Military Structure’

“Toussaint, [Ed] Watt, [Marc] Kagan and their supporters replaced the radical democratic vision that had been promoted by ND with a hierarchical, at times explicitly military, model of organization,” he continued. “In this model, all decision-making authority lay in Toussaint’s hands. At rallies, Toussaint was referred to as ‘our general’ and Kagan exhorted critics within ND to be ‘good soldiers’ and follow his leadership.”

The contract terms for which Mr. Toussaint settled in his first negotiation did not thrill a sizable minority of his members. That 2002 deal forced the union to forgo a first-year wage hike in exchange for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority providing an extra $46 million to make the union’s health fund solvent.

Mr. Downs contends that Mr. Toussaint was able to use a powerful tool to keep officers loyal to him: patronage jobs. The Local 100 leader made the decision to place several board members on payroll, leaving some reluctant to disagree with him and lose those salaries. The book outlines how this fear became reality during the 2002 contract talks.

A Costly ‘No’ Vote

“For most of them, being on the union payroll had meant a large pay increase and the obvious benefit of not having to work a dirty job under sometimes petty and abusive [Transit] supervisors,” Mr. Downs writes.

Several staffers lost their jobs when they voiced opposition to the contract terms to which Mr. Toussaint had agreed. But one case that stands out, Mr. Downs writes, is that of Mr. Kagan, a vice chairman of the union’s Car Equipment Division.

“A close ally of Toussaint’s for almost 20 years, he was serving as Special Assistant to the president during the contract talks,” Mr. Downs writes. “He wrote most of the union’s literature promoting the agreement. However, in the most striking demonstration of what would happen to a staff member who disagreed with Toussaint, Kagan was fired after he told co-workers from the shop he had worked in for over 15 years that he would be voting against the contract.”

As the 2005 contract talks came closer to the December deadline, Mr. Downs writes that Mr. Toussaint rejected the MTA’s demand that the retirement age and years of service be raised for new hires while requiring them to contribute more toward their pensions. The union went on strike for three days, but Mr. Downs contends that the local did little to prepare its members, and that the workers’ power was weakened by hostile news coverage, and lack of support from the TWU of America and the city’s other unions, which he claims either gave Local 100 milquetoast backing or asked that Mr. Toussaint end the work stoppage.

It ended without a formal contract, and when Mr. Toussaint presented the members with the tentative deal the next month, it contained one of the items that prompted the walkout: an MTA demand that they pay for part of their health coverage. The members rejected it by seven votes, only to have an arbitration award with similar terms imposed on them.

Became What He Fought

Since then, union dissidents have publicly complained that Mr. Toussaint is practicing the anti-democratic methods he fought against when he was a member of New Directions. Some officers in the union’s Private Lines Division have alleged that Mr. Toussaint has barred them from contract negotiations with MTA Bus, for example.

With the New Directions caucus dead, Mr. Downs said that many dissidents are doing the same type of organizing – holding meetings, staging demonstrations and publishing propaganda – against Mr. Toussaint that his group did against Mr. Hall and the two presidents after him.

Spokesmen for Mr. Toussaint did not comment on the book.

The 55-page book is available for one dollar, and readers can order it by e-mailing solidarity@igc.org, or by mailing $2 plus postage to Solidarity, 7012 Michigan Ave., Detroit, MI 48210.

John Samuelsen, a former Toussaint loyalist who will likely run for Local 100 president in 2009, said Mr. Downs had a fair take on the current president in his book.

“It’s not an attack,” he said. “He actually mentions some of the good stuff he did.”