by Dan La Botz

October 2, 2012

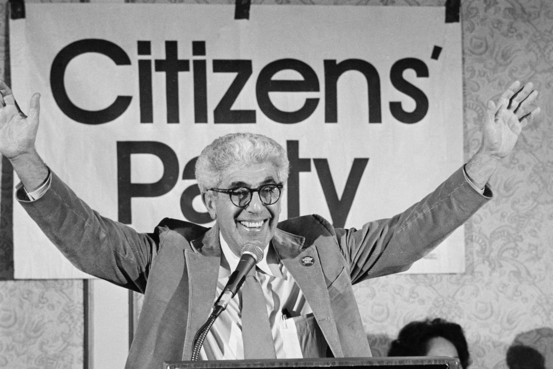

Barry Commoner, the great environmentalist, has died at the age of 95. I first learned about Commoner when in 1980 the socialist group of which I was a member, the International Socialists, decided to support his campaign for the presidency that year on the ticket of the Citizens’ Party. Our idea was that his campaign could bring together the social movements, particularly the environmental movement, and the labor movement.

Our idea was also Commoner’s. Having been educated as a youth in Marxism and then studying biology at Columbia and Harvard, he became not only the founder of the modern ecology movement, but the founding figure of eco-socialism. His early studies of the effects of nuclear radiation on children—-documenting strontium 90 in baby teeth-—led him to become a nationally known figure and turned him into an activist. Through public lectures and a series of books, the most influential being The Closing Circle, he educated the public and helped to educate a cadre of environmental activists.

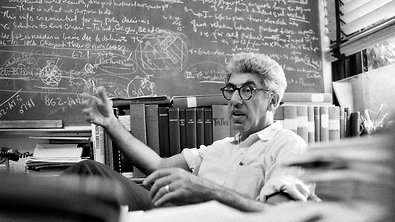

Barry Commoner in 1971 at Washington University in St. Louis.

Feeling at the time that I should know something about our candidate, I went and read his book The Poverty of Power. Having spent the previous ten years as an activist in the anti-war movement and then in the Teamsters union, I had neglected the environmental issue, and the book was a revelation to me. Commoner put the problem of power, of energy, into its economic and political context. His critique of environmental problems was rooted in his critique of capitalism.

In Chicago, the organizing committee of the Citizens’ Party was led by Dr. Quentin Young of Cook County Hospital, Studs Terkel the great writer and culture critic, and Sidney Lens, the labor organizer and historian. We also had organizers from the United Electrical Workers (UE), including one who had worked on the Henry Wallace campaign in 1948, and students from the University of Chicago who knew Commoner’s reputation. With Young, Terkel, and Lens leading our discussions, the meetings were wonderful talk fests and even did some organizing, including gathering petition signatures to put Commoner on the ballot in Illinois and Michigan.

I remember that organizers from the Consumers Party of Philadelphia, which formed part of Commoner’s Citizens’ Party, came to Chicago to talk about the campaign. One of their organizers told us, “You work as organizers and activists for years to build a movement, but you don’t create a political party, so you do the sowing and you let the Democratic Party do the harvesting.” Our job in the Citizens’ Party, he said, was to create a political expression of our work for democracy and militancy in the unions, against racism, against war, for women’s rights, and for a healthy environment. In the end, Commoner won only 234,000 votes, as Ronald Reagan defeated incumbent Jimmy Carter. But Commoner had raised all important issues.

The Democratic Party continues to do the harvesting. We have not yet had that convergence of social upheaval and political alternative which alone can provide the basis for fundamental change. But we continue to work to build the movements and alternative campaigns so that when that opportunity presents itself, we will be ready.

We have few chances in America to vote for candidates or causes we believe in. In 1968 I voted for Eldridge Cleaver, the Peace and Freedom Party candidate on the California ballot, though Dr. Benjamin Spock, the famous baby doctor, was the candidate in New York State. As the name Peace and Freedom suggests, it represented the convergence of the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s. Again in 1996 and 2000 I could cast my votes for Ralph Nader, the Green Party candidate whose consumer advocacy and social conscience had evolved into a campaign that had a socialist character, even if the word was never used.

Yet, I think that perhaps it was Barry Commoner’s campaign which represented the best values of an entire era in the US: on the side of the labor movement, for racial and gender justice, opposed to militarism and war, and for the protection of the environment. I thank Barry Commoner for having given us that opportunity and know that with his death, we have lost one of our most inspiring figures.

Dan La Botz is a Cincinnati-based teacher, writer and activist.