Nechama Sammet Moring, Ashley Houston, Bayla Ostrach

January 30, 2018

Even as many mainstream liberals and feminists recently celebrated the anniversary of Roe v. Wade, which solidified the legal right to abortion – for those who can afford it – economic inequality continues to limit abortion access. Being unable to access wanted abortion deepens poverty and vulnerability to other forms of social suffering.

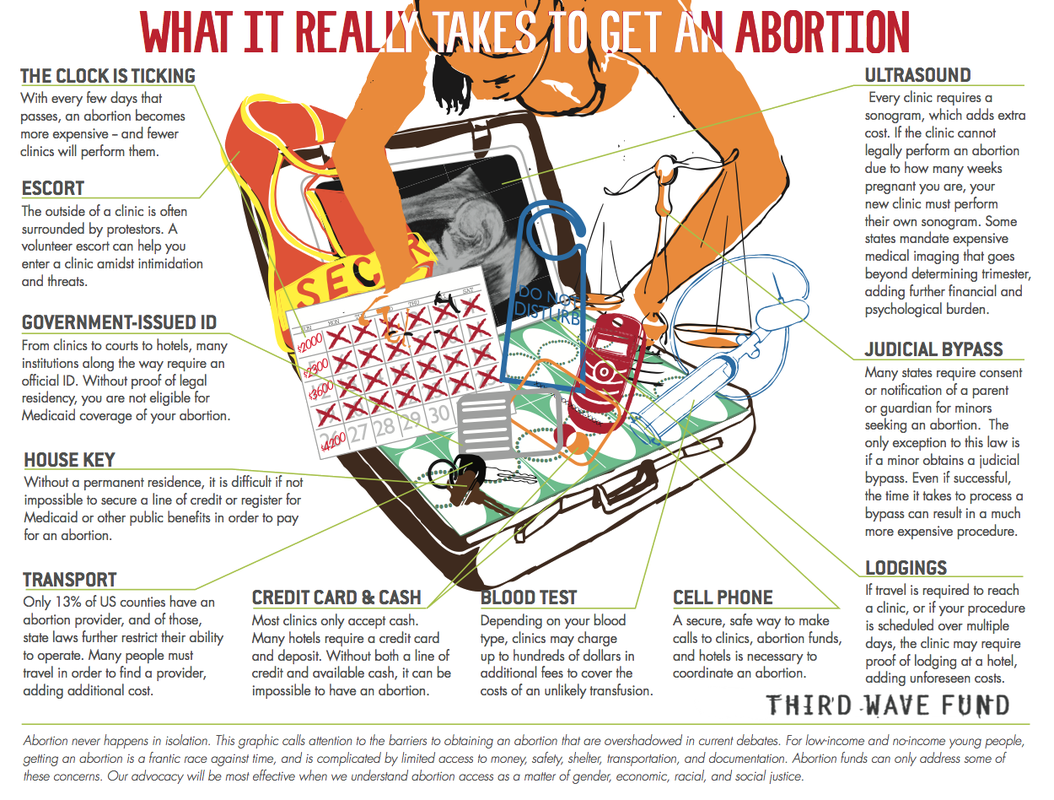

Economics of abortion access (Third Wave Foundation)

Economics of abortion access (Third Wave Foundation)Beyond abortion, poverty impacts many aspects of reproductive health and agency, and is more likely to be experienced by women, people of color, trans and gender non-conforming people, immigrants, people with disabilities and others oppressed in our unequal society. While perhaps less straightforward than simply safeguarding the legal right to abortion, ensuring true reproductive freedom is dependent upon righting economic inequalities that affect personal and community well-being — including expanding access to the full range of reproductive options.

Intersectional Reproductive Justice (Allied Media Project)

Reproductive Justice

Decades ago, Black feminist Loretta Ross coined the term reproductive justice to situate reproductive rights within broader social, political, and economic contexts. In this spirit, we present three stories, drawn from our collective research and activist experience, about the struggle for reproductive freedom in situations of economic and other inequality. They demonstrate the relationship between economic injustice, poverty, and the power to set one’s own reproductive course — the original impetus for Roe.

Nia’s Story: Nia, 28, is a queer, non-binary Black parent married to Alicia, a transgender woman. They use Masshealth (Medicaid). Nia had hoped for an unmedicated birth with their son, now 5, but felt hindered by frequent interruptions and rushed, unsupportive hospital staff, who misgendered them, referred to Alicia as their sister, and made belittling comments and racist assumptions. Nia felt overwhelmed by staff’s insistence that they comply with hospital rules (which weren’t based on medical evidence), and overpowered by their doctor’s insistence on frequent vaginal exams, which Nia, a sexual violence survivor, experienced as re-traumatizing. After 14 hours, Nia gave in to pressure to have a cesarean, for which they were not given adequate informed consent. They were later re-hospitalized for a cesarean-associated infection (a common complication after cesarean birth) contributing to the alarming rate of serious, preventable complications, especially among people of color in the U.S.).

Now pregnant again, Nia wants a vaginal** birth after cesarean (VBAC), and to be more in control of their experience. They think this is more likely to happen at home, with a midwife of color who understands their cultural and gender-related needs. However, Masshealth and private insurance don’t cover homebirth, and they cannot afford to self-pay. Nia nervously prepares for another hospital birth, telling Alicia that if their next birth is as traumatizing as their son’s, they will seek sterilization. The couple originally desired a large family.

Nia’s story reflects the U.S.’s liability-avoidant and profit-driven approach to childbirth (as opposed to decision-making based on medical evidence or the informed desires of the pregnant person). This has resulted in both higher healthcare spending and higher mortality than any other high-income country, especially for infants and birthing parents of color. This crisis was intensified by white public health officials’ 20th century push to eliminate Black midwifery. Medicaid-pay patients and patients of color receive lower-quality care and have higher rates of unnecessary interventions, including many that increase the odds of needing a cesarean, often resulting in trauma, hospital-caused injuries and worsened outcomes.

As hospital policies ban or curtail access to VBAC, typically a safer option than repeat cesarean, people who can afford it often turn to homebirth for evidence-based, personalized care for physiologic birth. In Massachusetts, where homebirth midwives are unlicensed, homebirth, as well as support, are not covered by Masshealth — and thus out-of-reach for many low-income folks. Efforts are currently underway to open a Black-owned birth center in Boston to address some of the constraints that limited Nia’s choices.

Birth Justice is Social Justice (graphic by Nick Anderson)

Birth Justice is Social Justice (graphic by Nick Anderson)Maribel’s Story: Maribel, 25, a U.S.-born daughter of low-income immigrant parents, was diagnosed with autism and a mild intellectual disability at age four. In school, Maribel was pulled out of her class for group tutoring, and missed the sexual health education her peers received. Maribel wasn’t supported with college applications or attaining a living wage job. After graduation, she started work in a sheltered workshop for disabled people, earning less than minimum wage. Maribel’s doctor assumed that disabled people are asexual, and handed Maribel a contraception pamphlet (which she couldn’t read) instead of providing the counseling and education she needed.

When George, a middle-aged co-worker, began pressuring Maribel for sex, she didn’t understand what was happening – or her right to decline- and she became pregnant. Unsure of pregnancy symptoms, she began prenatal care at 8 months. After Maribel gave birth, a postpartum nurse called the Department of Children and Families (DCF) when she noted the intellectual disability diagnosis in Maribel’s chart. The DCF social worker removed the child immediately, without due process, under the assumption that Maribel would not be able to parent her daughter.

Maribel and her family couldn’t afford private legal counsel to regain custody, and the assigned social worker monitored Maribel closely, subjecting her to intensive scrutiny, but did not advocate for her or teach her baby care skills. Maribel’s supervised visits with her daughter (now 2) are ending next month when the foster family she was placed with finalizes her adoption. Maribel is pregnant again and hopes that if she forgoes medical care, DCF won’t learn of her next child’s birth, allowing her to keep this baby.

Had Maribel gone to school in a higher-income district, she might have been diagnosed earlier, and thereby benefited from early intervention, improving her reading. She might have received English Language Learner support, or a 1:1 aide, allowing her to remain in class with her peers during sex ed; lacking sex education increases disabled people’s already high vulnerability to sexual violence. Economic justice in the form of accessible supports, equitable education, a living wage job, and legal counsel may have vastly improved Maribel’s access to real reproductive choice. Finally, DCF’s frequent but erroneous assumption that disabled people are unfit parents reflects historic eugenics-based practices attempting to limit parenting rights.

Taifa’s’s story: Taifa, a middle-aged mother of two, was circumcised in her native Somalia before immigrating to the U.S. Like other Somalis she knows, Taifa has had difficult experiences with U.S. reproductive health care. Taifa can only access one provider in the Boston area trained to provide care for circumcised women. Taifa’s family members in other areas of the U.S., where there are no skilled clinicians, are unable to receive preventative reproductive care altogether. Luckily, when Taifa’s children were born, she was able to work with a clinician who supported her desire to give birth vaginally. Yet, many of Taifa’s friends were pressured into cesareans due to language barriers and the fact that their providers did not know how to deliver circumcised women vaginally. Taifa says this is a source of frustration in her community, as Somali women have been vaginally delivering while circumcised for hundreds of years. Taifa feels that American providers are unwilling to listen to Somali patients’ needs and concerns, and has not been to a doctor in over five years.

Boston Somali women (photo by Ashley Houston)

Western clinicians are often unfamiliar, inexperienced, and, occasionally, visibly alarmed by female circumcision, and often do not have gynecological instruments small enough for circumcised women. This leads to poor communication, mistrust, patient dissatisfaction, as well as low rates of preventive screenings, pre- and post-natal care and reproductive health disparities These biases in healthcare reflect the compound discrimination displaced Somalis face due to skin color, Muslim religious identification, and/or perceived immigration status. Like Taifa, immigrant women are more likely to live in poverty and less likely to be represented in clinical settings or have access to appropriate health care.

Taken together, the stories of Nia, Maribel and Taifa represent some of the many ways that economic inequity limits reproductive freedom, especially for those of us who live at the margins. These stories also illustrate that, as Black reproductive justice scholars point out, true reproductive freedom includes dismantling the economic and social inequities that eat away at access to multiple forms of reproductive care. It is time for reproductive justice to extend the victories of Roe to all.

What can YOU do?

- Support reproductive and birth justice in your community – be an ally to efforts like Southern Birth Justice Network, SisterSong, SisterLove, Birth Sanctuary Boston, and other community-based collectives such as those organized and led by activists, doulas, and midwives of color. Consider supporting coalitions advocating for Medicaid and insurance coverage of doula care and homebirth, to expand access for low-income folks.

- Don’t assume you know or understand someone’s cultural background, gender identity, the terminology they prefer for sexual and reproductive health discussions, or what is best for people or their bodies in those contexts — especially if you work in or around healthcare. Listen to people’s experiences, preferences, and questions. Become a queer and trans-friendly provider – resources and training are available.

- Fund abortion, through your nearest member fund of the National Network of Abortion Funds. Provide practical support by volunteering on a hotline or to offer shelter or transportation for folks in need of solidarity to overcome logistical obstacles to abortion.

- Make sure your feminism is intersectional, inclusive and committed to true reproductive justice, beyond the more widely discussed right to access contraception and abortion. Reproductive justice involves examining the context in which people make choices, and working to ensure that all people and communities have equitable access to true choice, including and especially people who are marginalized in our society, such as people of color, trans, non-binary, and gender non-conforming people, immigrants and people with disabilities.

**Vagina is the term Nia prefers for their genitalia, noting that they do not consider vagina to be a gendered term or body part, in the same way that their kidneys are not gendered. Correct terminology of course varies by individual, and individuals should always be asked how they refer to their own bodies and identities.↩

Nechama is a midwife, a participatory action researcher focused on health equity, and a science writer at her company Rebel Girl Research Communications where she blogs about science and social justice.

Ashley is a medical anthropologist, community-engaged researcher involved in the Greater Boston Muslim Health Initiative, and former member of Boston Solidarity.

Bayla is an applied critical medical anthropologist, long-time abortion provider, and Solidarity member active with the Gendered Violence Commission.