by Steve Early

September 4, 2014

For many years, American unions have been trying to “organize the unorganized” to offset, and, where possible, reverse their steady loss of dues-paying members. In union circles, a distinction was often made between this “external organizing”–to recruit workers who currently lack collective bargaining rights–and “internal organizing,” which involves engaging more members in contract fights and other forms of collective action aimed at strengthening existing bargaining units.

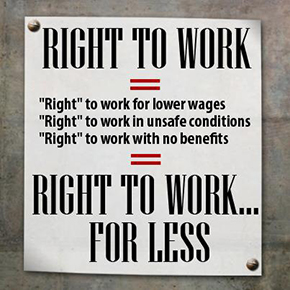

Thanks to the growing success of corporate-backed “Right-to-Work” campaigns, these two forms of union outreach now greatly overlap. Virtually all labor organizations face the expanded challenge of recruiting and maintaining members in already unionized workplaces where the decision to provide financial support for the union has, for better or worse, become voluntary. (Some left-wing critics of “contract unionism” have long argued that automatic deduction of dues, by employers for their union bargaining partners, makes the latter overly dependent on management and less responsive to rank-and-file workers.)

Throughout the country, labor foes have succeeded in limiting the ability of unions to collect dues, or the equivalent in “agency fees,” from more of the 16 million workers they are legally certified to represent. In the private sector, 24 states now have an “open shop,” which means that union membership or fee paying by non-members cannot be required in contracts with employers, including, most recently, those operating in Michigan and Indiana.

In the public sector, the parallel legal/political assault on “union security” agreements and automatic deduction of dues or fees from government employee paychecks has unfolded in those two states, neighboring Wisconsin, and every state with recently created bargaining units for home-based direct care providers.

With adverse ramifications for 700,000 similarly situated union-represented workers in other states, the Supreme Court ruled, in June, that publicly funded home health care aides in Illinois were only “quasi-public employees.” According to the Court’s decision in Harris v. Quinn, they are no longer subject to the requirement, under local public sector labor law, that non-members pay their “fair share” of the cost of union representation and services which unions must provide to everyone in their bargaining units.

Membership Exodus

When Service Employees organizer Rand Wilson and I wrote about this emerging trend two years ago, in an essay for Monthly Review Press entitled “Union Survival Strategies in Open Shop America,” we noted that there were already more than 1.5 million Americans covered by union contracts, who had declined to become members. Based on developments then underway in the mid-west, we predicted that the guaranteed revenue stream that many U.S. labor organizations had long enjoyed–and used to pay for their large complement of lawyers, lobbyists, full-time negotiators, and field staff–would soon be interrupted.

For example, in Wisconsin, where public employees had just been battered by contract concessions and then stripped of meaningful collective bargaining rights, most of their unions had not functioned as voluntary membership organizations for three decades or more. We expressed the concern that a new, more intimidating workplace environment might combine with rank-and-file resentment over wage and benefit give backs to send dues receipts plummeting–if unions did not move quickly to strengthen their shop-floor presence.

In Indiana, from 2005-11, a similar Republican revocation of “dues check off” and more limited bargaining rights caused state worker union membership to drop from 16,400 to less than 1,500. In Michigan, after legislators excluded home care workers from their state’s definition of public employees and stripped them of bargaining rights granted by a previous Democratic governor, membership in the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) declined by 80%–from 55,000 members to less than 11,000 in a single year.

Painful Transition

As The New York Times reported last February, the forced transition to a new model of functioning has been no less painful in Wisconsin. Since Republican-backed Act 10 “severely restricted the power of public employee unions to bargain collectively,” the state worker membership of the American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) “has fallen by 60 percent; its annual budget has plunged to $2 million from $6 million.”

Founded in 1932 as a pioneering AFSCME affiliate, Madison-based Local 1 went from 1,000 to 122 members. To keep the union alive, “99 percent of what the staff does is organize,” explained AFSCME council director Marty Bell. “Without the ability to bargain, Bell’s union mostly represents members and engages in collective action,” according to The Times. Local affiliates of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) have been similarly decimated—in part because of official resistance to lowering dues—while their counterparts in the National Education Association (NEA) had done better maintaining Wisconsin membership.

Now comes Michigan again, where the most recently enacted state “right to work” law is going into effect for 112,000 public school teachers, who represent one out of every six union members in the state. During all of August, they’ve had a chance to “opt out” of paying for their union representation. In a previous “opt out” period last year, only 1,500 or 1% did. But this summer, teachers have been bombarded with anti-union mailers and newspaper ads–the latter purchased by Americans for Prosperity, a Koch brothers creation. These have urged them to withhold annual payments of up to $822 to the Michigan Education Association and its parent organization, the NEA.

Michigan union members protest the state’s adoption of Right to Work.

Other major unions in Michigan, including the United Auto Workers (UAW) have multi-year contracts that are in effect until 2015 or later. When those expire, more private sector union members will have the same choice as teachers this summer. As the Associated Press reported August 25, “a significant number of drop outs would deliver a financial blow to labor in a state where it has historically been dominant”—or, at least, far more influential in the past than today.

When a cash-strapped UAW hiked its dues earlier this year, opponents of that measure warned that higher dues might discourage more of the union’s 50,000 Michigan-based autoworkers to drop out next year. Of particular concern is the simmering resentment of more recently hired UAW dues payers, who are demanding changes in the Big Three’s two-tier wage structure that leaves them far below the hourly pay of higher seniority workers. If that issue is not satisfactorily resolved in the next round of auto industry bargaining, the Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity may even gain traction in a few auto plants.

Pre-Emptive Organizing Needed

In an anticipation of an unfavorable ruling in Harris v. Quinn, some SEIU and AFSCME locals, with large numbers of home-based workers paying agency fees rather than dues, stepped up their efforts to convert them into actual members, who would stick with the union when and if “free riding” became possible. These efforts have paid off, in some places, but still have a long way to go in SEIU affiliates like United Long Term Care Workers in California. SEIU-ULTCW has publicly claimed to have 170,000 “members” at the same time its U.S. Department of Labor filings showed that 80,000 or more were, in fact, just “agency fee payers,” with no membership rights whatsoever and, apparently, little connection to the union.

Newer additions to the nation’s unionized homecare workforce—like the statewide unit of 27,000 personal care attendants in Minnesota who won union recognition August 26—will need continuous internal organizing, to boost their post-election membership levels. In that new group, only one fifth of the workers eligible to vote actually cast a ballot for or against SEIU, which won by a margin of 60-to-40%. In an open shop environment, under a less friendly governor, the other 21,000 could easily go the way of SEIU’s now lost dues paying majority in Michigan home care.

As former SEIU organizer Jane McAlevey has argued, based on her past union experience in open shop Nevada, “even in the face of campaigns by employers to get workers to drop their membership, workers will continue to be members and contribute from their paycheck when they experience their union as their union.”

Ironically, some of the best examples of what McAlevey calls the “high participation model” of union building can be found in southern “right-to-work” states. As Wilson and I reported in our “open shop” organizing chapter in Wisconsin Uprising: Labor Fights Back (Monthly Review Press, 2010), “non-majority” unions have been constructed by public sector members of the Communications Workers of America in Tennessee, Texas, and Mississippi and the United Electrical Workers in North Carolina—all in the absence of formal collective bargaining and any mandatory payment of dues or fees.

These member-driven labor organizations have devised more reasonable dues structures, ways of collecting dues voluntarily, and, most important of all, a workplace and community presence not defined by employer recognition or statute. Their survival and effectiveness depends on worker activity–the kind of member mobilization around job-related and legislative/political issues that labor needs, in many other states, to remain “organized” without the legal props of the past.

Steve Early worked for 27 years as an internal and external union organizer for the Communications Workers of America. He is the author, most recently, of Save Our Unions (Monthly Review Press, 2013). For more on his work, see his website or contact him at Lsupport@aol.com.