by Román Munguía Huato

April 4, 2014

Translator’s introduction:

Mexico’s ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party’s (PRI) privatization of the country’s energy industry in December of 2013 was received with applause and glee by the U.S. and European financial press. The privatization of Petróleos Méxicanos (Pemex) is,

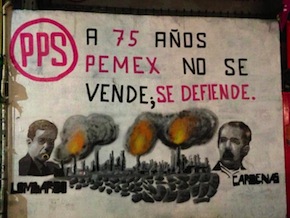

A sign at a demonstration opposing the privatization. It reads: “75 years later Pemex will not be sold — it will be defended.” according to one corporate advisor referenced in the Financial Times, “on a par with NAFTA in terms of macroeconomic significance.” Oil investor Kent Moors, blogging about his presentation to a Bloomberg-hosted conference in Mexico City on new oil investment opportunities, gloated that the privatization “promises to open up a series of unprecedented money-making opportunities for a select group of companies—and their investors.” So while investors pulled $18.6 billion out of emerging markets in the first five weeks of 2014—destabilizing currencies, increasing poverty and hardship, and threatening global economic stability—investors are eyeing Mexico as “a hidden gem.” As one Money Morning economist sneered, it is “Time to profit” now that “outsiders can become insiders that take part in Mexico’s renewed emerging market—and net huge gains as a result…” Two-thirds of Mexico’s oil and gas fields have been auctioned to private investors, a quantity potentially equivalent to the last 110 years of domestic oil production.

In the 1920s Mexico was the second-largest producer of oil in the world, but the country gained little from it. After years of labor organizing and military repression, a 1936 oil-workers’ strike paralyzed the country for twelve days and led directly to Cardenas’ hugely popular expropriation two years later. The United States and Britain imposed an international embargo on Mexican oil that decreased exports by 50% and supported company demands for exorbitant compensation.

On March 18th, the 76th anniversary of President Lazaro Cardenas’ expropriation of the American and British-owned oil fields, refineries, and shipping docks, a variety of demonstrations and marches led by the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), the new National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), the National Union of Workers (UNT), the New Workers Central (NCT), Mexican Electrical Workers Union (SME), the National Coordinating Committee (la CNTE, a dissident caucus within the Mexican Teachers Union) and by the People Congress for a Constituent Assembly and other social movements and local organizations were held in Mexico City and throughout the country in opposition to the neoliberal energy reforms. Expressing the same anti-imperialist politics that drove Cardenas’ expropriation, demonstrators in Jalisco marched under Mexican flags and homemade signs chanting, “No, no, no we don’t want to be an American colony, we want to be a free and sovereign country.” (No, no, no, no nos da la gana de ser una colonia norteamericana; sí, sí, sí, sí me da la gana, ser una nación libre y soberana.)

* * * * *

It was mere ironic coincidence that on the date of the oil expropriation the newspapers inform us that at the top of the social pyramid ten Mexican mega-billionaires hoard 133 billion dollars, which means that the annual income of almost sixteen million households equals less than two thirds of their fortune. That is to say, ten Mexicans possess an income that is almost as great as that of 80 million Mexicans. These dozen Mexican capitalists, with investments in telecommunications, mining and trade, hold a fortune of 132.9 billion dollars, around 1.8 billion pesos, according the list by Forbes magazine. The fortune of the ten magnates—Carlos Slim Helú, Germn Larrea, Alberto Bailleres, Ricardo Salinas Pliego, Emilio Azcárraga Jean, Eva Gonda de Rivera, María Asunción Arumburuzabala, Antonio del Valle Ruiz, Jerónimo Arango—is equivalent to 11 percent of the total goods and services produced in Mexico in one year, measured by gross domestic product (GDP), currently calculated to be 16 billion pesos.

This concentration of wealth correlates increasingly with social poverty. In Mexico, four of each ten persons do not have money to buy food, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). One of every five inhabitants live in extreme poverty and one of even two live in poverty. This situation is a product of the neoliberal privatization policies that began in 1982, and certainly will be aggravated further with the “structural reforms” imposed by Enrique Peña Níeto’s Pact for Mexico [a governing alliance of the three major political parties—PRI, PRD and PAN.]. The so-called energy reform is the privatization of the petroleum resources for the benefit of the local and foreign oligarchy. This reform in fact is a transnational subordination—Exxon, Chevron, Shell, Halliburton, Schlumberger, etc.–but this is especially a submission to the imperialist interests of the neighboring country to the north.

Peña Nieto.

This March 18th the official celebration of the oil expropriation that Lázaro Cárdenas del Río undertook in 1938 was led by Peña Níeto, the leader of the oil union, Carlos Romero Deschamps, the Secretary of energy, Pedro Joaquín Coldwell, the director of Pemex, Emilio Lozaya Austin, and the governor of Veracruz, Javier Duarte–the same governor accused of assassinating at least ten journalists. The ritual was nothing more than a pathetic act of simulation and cynicism. It is said that one of the most important derivatives of petroleum is corruption, as deep as a hydrocarbon well. Oceanographic [the Mexican oil services company under investigation for fraudulent dealings with Citibank via Pemex] is a visible example; one more recent scandal of the Mexican state.1

But the culmination of the corruption and cynicism is the ovation received by the corrupt union boss [charro] Carlos Romero Deschamps as speaker during the ceremony when Peña Níeto insisted, falsely, that the state will continue to be owner of Pemex. The fact that Romero Deschamps was present speaks to the nerve of the profound corruption that encloses government petroleum policies with looting and multimillion dollar frauds, as in Oceanography, the tip of the iceberg. To speak of this union charro super-millionaire is to speak of one of the principal masters of the union mafia, as journalist Francisco Cruz Jiménez tells us in his book. This union “leader” should be in prison same as the imperious “leader” Elba Esther Gordillo, but is an example of decency and of the petroleum union’s struggle as far as Peña Níeto is concerned.

For the past thirty years the neoliberal governments have been taking from, dismembering and embezzling Pemex to present the public with their “argument” that Pemex needs “regime change,” a euphemism used to hide the true intention of privatizing the most important enterprise in the county and in Latin America. The struggle against privatization of the energy industry was initiated in 1999 by the Mexican Electricians Union (SME). It is a struggle with profound class consequences. If Pemex and the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) are to be preserved as national inheritance and not as private business, the workers in this industry are the ones who will guarantee this condition. The government bureaucracies are completely intertwined with the interests of the capitalists and the corrupt union charros are their accomplices. The struggle against the privatization of Pemex is not a mere “nationalist” fight but a chapter in the class struggle of the Mexican workers to recuperate their country and avoid its complete alienation to the imperialist of the United States and the major world oil companies. If this struggle triumphs, the destiny of the energy industry will not remain in the corrupt hands of the PRI, PAN, or PRD politicians, nor will it be looted by the union charros anymore. It should be the start of a struggle for a non-capitalist economic project, aimed at meeting the needs of the masses and in which the participation of the workers is the key to democratization and to prioritizing collective interests and not the capitalists’ profits.

The struggle for national sovereignty requires the re-nationalization of the energy industry, primarily of the petroleum industry. That is why on Monday evening Guadalajara saw a highly combative march and rally of the Popular Front Against Privatization of the Energy Industry, adding to the call of the People’s Congress. During the march a contingent stopped in front of the U.S. consulate to read a manifesto, affirming that U.S. oil companies are the principal beneficiaries of the energy reform.

Román Munguía Huato writes on Mexican politics regularly for Rebelíon. Translated by Connor Donegan, a member of Solidarity.

Footnotes

1 From Reuters: “The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating Citigroup for accounting fraud after it disclosed bogus loans in its Mexican Banamex unit… The bad loans were made to Mexican oil services company Oceanographic, whose assets Mexican law enforcement officials have now seized. The oil services company was a contractor for Mexican state-owned oil company Pemex.”