by Dan La Botz

August 31, 2013

We thought we might be getting beyond this with the Arab Spring, but here we are again facing war in the Middle East. We have lived for decades in fear of a regional war in the Middle East. Now we are at one of those points where once again it seems not like some distant danger but a real possibility. The United States is threatening to bomb Syria in retaliation for its alleged chemical attack on hundreds of civilian non-combatants, a plan opposed by Russia and Iran, and rejected by the Arab League and also independently by Egypt. Iran has announced that if Syria is bombarded by the U.S. that it will in turn attack Israel.

Well informed people consider Iran’s threat a bluff, pointing out that Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has been restrained in his statements. Still the possibility of Iran taking action should not be rejected out of hand, as new pressures on the Bashar al-Assad regime could lead its Iranian ally to react in unexpected ways. Given the historic ties and treaties between governments in the region one cannot be sure exactly how events will unfold. And that is the greatest danger. A U.S. attack on Syria, even the “limited” strike that has been proposed, can bring in its wake unforeseen consequences that could upset the existing shaky balance of forces in the Middle East leading to a broader war.

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

While it was wonderful to learn that the British Parliament had voted to reject a so-called humanitarian intervention in Syria, we should have no illusions in the government of the United Kingdom. Still it is clear that the House of Commons felt that the British public could not be sold this bill of goods again—at least not yet. Still, François Hollande’s Socialist Party government in France says that it backs the United States and that it is prepared to act without Great Britain. Russian President Vladimir Putin has challenged the United States to present evidence of the use of chemical weapons to the United Nations, where Russia will surely block any resolution to take action against Syria.

President Obama, his personal credibility at stake after his statement that use of chemical weapons was a “red line,” seems bent on a military strike that has clear positive benefits for the United States. Secretary of State John Kerry suggested that Assad must be punished for his violation of a fundamental international principal that such weapons of mass destruction cannot be used against a civilian population. Yet the claim that the United States holds to a higher standard rings hollow given the long American history of the use of weapons of mass destruction against civilians from the fire bombs dropped on Dresden, to the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to the carpet bombing and napalm bombing of Vietnam, to the white phosphorus used against Iraqis. Not to mention the drones used in Pakistan.

The United States will be supported in this action only by France and Turkey, though Saudi Arabia will be providing the money and guns to fighters on the ground working to overthrow Assad. Like Iraq and Afghanistan, an attack on Syria could prove another intractable problem for the United States, an imbroglio for the diplomats, and a greater tragedy for the people of the Middle East. The irony here is that there is no clear gain for the United States in taking such an action. It will not overthrow Assad. It shows the political weakness of the United States in its failure to create a coalition to undertake such an adventure. And it will surely fuel the anti-American and anti-Western sentiment in the region. At the same time, it will encourage other regional powers on various sides of the conflict to inject themselves even deeper into the situation.

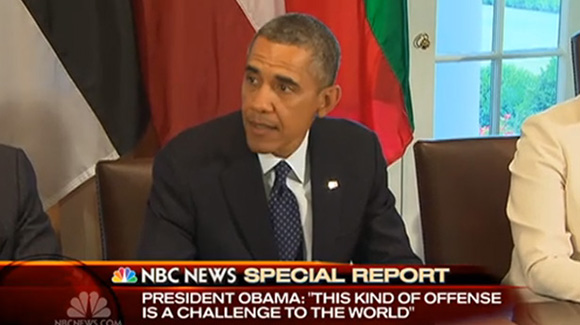

President Obama discussing intervention in Syria.

The depressing situation in the Middle East had been held in suspension—a reactionary peace—for at least two decades by the Great Powers (the United States, Europe, and Russia), other neighboring states (Turkey and Iran), and by the dictators in the region, as well as the rightwing government of Israel. A new era of change and instability opened with the Arab Spring that erupted in 2010, a democratic movement that toppled rulers in several nations and saw mass democratic protests throughout the region. By 2012 Spring had turned to Fall as a combination of foreign intervention, an upsurge in Islamic fundamentalism in some states, and the entrenchment of authoritarianism in others chilled the movement. In Egypt the Spring was short, the Fall shorter, and Winter set in with the military coup that overthrew the Muslim Brotherhood government of Mohamed Morsi.

Syria became the site of the most intense and ultimately the most violent confrontation between democratic reform forces and authoritarianism, fundamentally because of the narrow demographic and social base of the government of President Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian branch of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party which he leads. The state security forces and the military are dominated by the Alawite sect, though over the years the Assad regime also created ties to the Sunni bourgeoisie through government contracts. The Syrian peasantry which once supported the “socialist government” has been left behind. Consequently, because of its narrow social base, Assad has relied on its security forces and the army to buttress the regime, even if it has meant the destruction of much of the country and the death of tens of thousands.

The Arab Spring’s democratic movement thus represented a tremendous threat to Assad, to his one-party state—the Socialist Ba’ath Party is constitutionally the “leading party.” The Spring was a threat in Syria to the Sunni bourgeoisie and to the government’s Alawite and Christian supporters. The massive democratic protests from January through March of 2010 were met with the Assad government’s violent repression on March 18-19. After that that came the civil war, the more than 100,000 killed, the more than 1.5 million refugees, and the destruction of cities and towns throughout Syria.

The Syrian Civil War became an opportunity for covert intervention by the Great Powers, the regional powers, and by the rightwing Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). The democratic and progressive forces in Syria, as in Egypt, though they still exist, have been marginalized by the conflict between secular authoritarianism (ironically sometimes called “socialism”) and an equally reactionary religious fundamentalism. The great and potentially transformative process that opened with such hope in Tunisia in December of 2010 has brought us now to Syria in August of 2013 and to the possibility of a regional conflagration.

A member of the Free Syrian Army observed an anti-Assad demonstration.

The new era of Middle Eastern instability that began with the

Arab Spring three years ago represented the greatest threat to Great Power domination of the Middle East since the United States replaced Great Britain as the hegemonic force in region at the end of the Second World War. Once again, as at the time of World War I and World War II, there was the possibility of a great Arab Awakening, that is, of a combination of anti-colonialism, regional self-determination, a chance for democracy, and the more distant possibility of socialism.

Nothing could be more horrifying to the Western Powers that have dominated the Middle East since the 1860s, and which by the twentieth century controlled access to the region’s tremendous and all-important petroleum deposits. The West’s domination of the region depended above all on control of Egypt and the Suez Canal and domination of the eastern end of the Mediterranean, of the Levant, that is, of Israel, Palestine, Jordan, and Syria. And that’s why it had all now come down to Egypt which has the canal and to Syria which commands the heights of the Levant.

The great confrontation underlying everything remains that between the Arab peoples and the Western Powers, generally refracted through the Arab Spring’s democratic movements, as well as in distorted ways through dictatorial governments and Islamic fundamentalist groups. Yet Russia, Iran, and Turkey have their interests here too, authoritarian states that would like a greater share in the wealth of the Middle East, greater influence in the Arab world, and that like the Arab dictatorships and the Israeli rightwing government, also fear the democratic movement that might spill over into their reactionary and obscurantist regimes. Along the great arc from Siberia to Syria, it often seems that democracy is a flickering candle and socialism a match held in the wind. Our job is to protect the flame, to blow on the ember, to keep the fire alive.

The West’s talk of defending human rights and upholding democracy, as everyone knows, is cant, pure hypocrisy. The Great Powers have no more interest in those things than they do in freedom or justice, all of which are hollow slogans of lying diplomats who speak for their governments at press conferences. When they talk about “our interests,” however, they are telling the truth; they are prepared to fight for their interests. Today, as U.S. President Barack Obama considers a strike on Syria, his problem is that how to defend “U.S. interests,” that is, how to defend American geopolitical goal of remaining the hegemonic power in the region, maintaining access to the oil and control of the canal and the Levant. Ultimately, of course, there must be the reestablishment of reliable governments, that is, of Arab governments that can be trusted to cooperate in the protection of American interests.

Victims of the chemical attack.

At one point, early in the Arab Spring, Obama talked as if he would like to see the movement sweep away the authoritarian regimes and perhaps replace them with reliable democratic governments more attuned to the new global neoliberal order. Though not Bahrain, of course, which is home to the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet, and not in…well, not anywhere actually. As shown particularly in Libya, Syria and Egypt, that path of even capitalist democratic change has proved too tortuous and dangerous; the political road seems to be mined with popular democracy on the one side and with Islamic fundamentalism on the other. Better then to support the Egyptian military’s return to power than to risk a democracy which might become all too genuine.

But what to do in Syria? That is the question Obama and the West now faces. Limited military intervention of the sort Obama contemplates will have little effect on the Assad regime, and will certainly do nothing to help the people of Syria. The blow-back from it could strengthen the Islamic fundamentalists, which in turn could strengthen the authoritarian regimes that present themselves as the bulwark against religious reaction. Or they could, through some miscalculation on the part of one or another of those involved, unleash the great Middle Eastern War we have all feared. Failing to take any action, however, permits an unraveling of the Levant that threatens the Western Powers.

What are our options? What can those of us who believe in democracy and want peace do in this situation. First, of course, we can continue to oppose Obama’s threatened attack on Syria and we can continue to stand against military intervention by any foreign power. At the same time, we can continue to stand against Assad’s authoritarian “socialist” government, as well as against reactionary groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. We can support the genuinely popular and democratic groups in Syria, especially the grassroots networks of farmers, workers, women and others who struggle to build a different society from below. While they are not always very visible, within the ever changing and shifting constellation of forces in the opposition to Assad, they still exist.

The democratic and popular voices in the Middle East have been silenced by the roar of the reactionaries, secular and religious, and sometimes seem to be a voice whispering in the wilderness. We in the democratic and socialist movements in the West can raise our voices against foreign intervention while we support the democratic opposition and wait and work for a new year and a new Spring.

Dan La Botz is a member of Solidarity in Cincinnati, and an editor of New Politics.